1. Introduction

Amid the advancing tide of globalization, the development of intercultural communication competence and international perspectives has become a central goal in the training of language majors in higher education. As a core component of language-related disciplines, linguistics courses directly influence students’ cultural sensitivity and ability to adapt to intercultural contexts [1]. Integrating intercultural communication instruction enriches students' understanding of cultural differences, enhances critical thinking, and broadens their global outlook. Graduates with strong global competence are gaining significant advantages in fields such as academic research, professional communication, and public service. Therefore, examining the influence of intercultural communication teaching within linguistics courses is essential.

This study adopts the classical grounded theory methodology to construct a model illustrating the pathway through which intercultural communication instruction in university linguistics courses influences the development of students’ international perspectives. It seeks to uncover the internal causal relationships and interaction mechanisms involved. This research aims to provide practical reference for curricular reform and international talent cultivation in language education.

2. Literature review

Foundational research in intercultural communication instruction began with Edward T. Hall’s The Silent Language, stressing the deep relationship between culture and communicative behavior, laying the groundwork for the study of intercultural communication [2]. Building on this, Gudykunst contributed to the disciplinary development of intercultural communication by proposing theoretical frameworks such as the Anxiety/Uncertainty Management (AUM) Theory, highlighting psychological adaptation processes in cross-cultural exchanges [3]. However, their theories lack inclusivity in addressing intercultural patterns among non-Western cultures, limiting their applicability in today’s diverse educational settings. Byram later proposed the widely cited model of Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC), advocating for the integrated development of attitudes, knowledge, and skills in language education [4]. While his framework emphasizes critical cultural awareness, it pays insufficient attention to conflict mediation strategies in real-life intercultural interactions, making it less effective in guiding high-complexity teaching scenarios. Deardorff approached the issue from the perspective of global competence, using the Delphi method to construct a model for assessing intercultural competence that integrates cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions. This model has been adopted by international bodies such as the OECD [5]. However, it lacks guidance on dynamic instructional strategies and teacher mediation in specific settings, as well as longitudinal research to track changes in intercultural competence over time. Other scholars advocate for the systematic integration of local cultural content into language teaching and suggesting innovative tools such as audiovisual media for classroom use [6,7].

In summary, most are based on individual scholarly perspectives and face limitations such as narrow cultural applicability, underdeveloped practical models, and insufficient guidance for micro-level educational scenarios. These gaps suggest the need for further development of more localized and diversified intercultural education frameworks that promote dynamic and systematic development of intercultural competence and global vision.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Research participants

This study adopts a qualitative research approach grounded in the methodology of classical grounded theory. It focuses on three groups of university students with cross-cultural language learning backgrounds. The selection of these three groups aims to enable a comparative analysis of the commonalities and differences in how intercultural communication instruction influences the cultivation of students’ international perspectives. To ensure the authenticity and richness of the narratives, interviews were conducted in the language most familiar to each participant. When necessary, participants were encouraged to respond in their acquired second language. The details of all interviewees are presented in Table 1.

|

name |

nationality |

school |

major |

grade |

current location |

|

|

Participant A |

Yinqi Lin |

China |

Beijing Foreign Studies University |

Vietnamese, minor in Chinese Language |

Junior |

Beijing, China |

|

Participant B |

Đinh Thoại Huyền Vi |

Vietnam |

University of Thanhlong, Beijing Foreign Studies University |

Business Chinese (Specialization in Business Management Chinese) |

Graduated with a Bachelor's Degree |

Hanoi, Vietnam |

|

Participant C |

Zhengzhen Huang |

China |

University of Xiangtan, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies |

English Interpretation |

Graduated with a Master's Degree |

Guangdong, China |

3.2. Data collection

This study employed semi-structured, in-depth interviews. Following Seidman’s three-interview series approach, each session lasted 30–60 minutes and transcribed and organized for further analysis. The interview outlines were tailored for the three student groups, incorporating common questions and group-specific scenarios [8]. Initially, the interviews aimed to make participants comfortable, especially those not speaking their native language, by asking about their current location, university schedule, and daily learning experiences. The first interview focused on participants’ life histories, asking them to describe their background, personal growth, education, and early cross-cultural language learning experiences in detail. The second interview aimed to reconstruct the details of their current cross-cultural experiences, prompting vivid accounts of specific events and interactions. The third interview encouraged participants to interpret and construct meaning from their experiences, guiding them to reflect on the cognitive and attitudinal changes brought about by these encounters [9].

3.3. Data analysis

The study followed the comparative analysis principles of grounded theory. During the open coding phase, raw interview data were systematically examined, with significant concepts identified and assigned initial categories [3]. Through this process, primary codes are illustrated in Table 2.

|

Initial Concepts (Open Coding) |

Initial Categories |

|

Stereotypes Dislike for the major Elimination of prejudice Enrichment of cultural awareness |

Existing cognitive foundation and emotional attitudes Enhancement of cultural awareness Transformation of attitudes and emotional changes |

|

Integration of target cultural knowledge in teaching The other people felt pleased and considered me polite |

Teaching Content and Strategies Development of intercultural competence through practice |

|

Broadened global perspective Shift in cultural observation perspective based on one’s own cultural background and foundation Biased or unrealistic perceptions Courses with an Intercultural Perspective |

Global awareness and expansion of vision Original cognition, cultural foundation, and emotional attitudes Integration of intercultural elements into courses |

|

Initial impression of cultural richness Lack of understanding, condescension, and a sense of distance in communication |

Existing cognitive foundation and emotional attitudes Transformation of attitudes and emotional changes |

|

Richer cultural products and information sources Personal interest |

Globalization Context Learning motivation |

|

Dialogue exercises Understanding the cultural logic behind language Comparing differences in concepts Deeper understanding of society and values Chinese students |

Intercultural teaching and interactive experiences Enhancement of cultural awareness Integration of intercultural elements into courses Peers with diverse cultural backgrounds |

|

Greater respect for others’ cultural acceptance Change in stereotypes Correction of misunderstandings Enhancement of communication skills More open, bold mindset |

Cultural Comparison and Reflection Improvement in communication and interpersonal skills Transformation of attitudes and emotional changes |

|

Addition of “Intercultural Communication” modules Comparison of differences in thinking patterns and values between China and the West |

Integration of intercultural elements into courses Cultural comparison and reflection |

|

Improved ability to resolve communication misunderstandings and to view the world with an open mind Recognized that cultures have no hierarchy Differences in modes of expression |

Enhanced Communication and Understanding Skills Cultural comparison and reflection |

|

Correction of stereotypes Elimination of bias Self-reflection |

Cultural comparison and reflection Transformation of attitudes and emotional changes |

|

Engagement with social issues Increased curiosity Cultivation of an international perspective Enhanced confidence in intercultural communication |

Socio-cultural Context Transformation of attitudes and emotional changes Global awareness and expansion of vision |

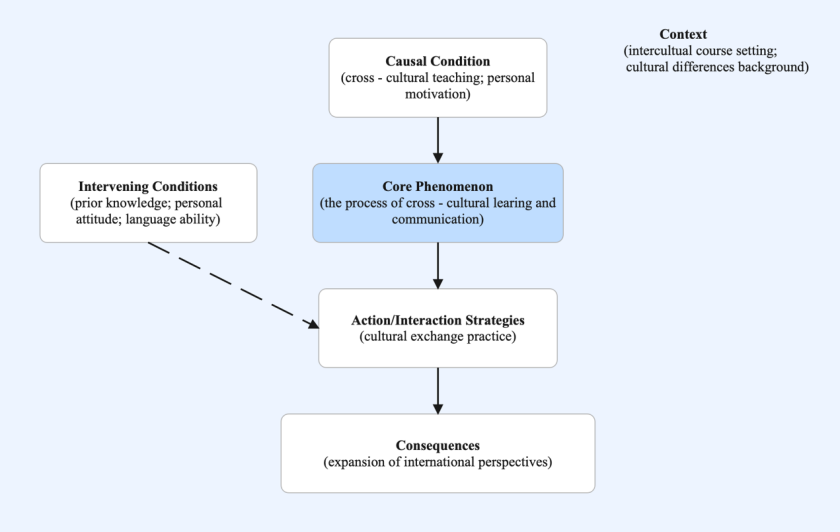

During the axial coding stage, this study followed the paradigm model of grounded theory. Through comparison, analysis, categorization, and aggregation, the open coding categories were integrated according to the logic of “causal conditions—core phenomenon—context—intervening conditions—action/interaction strategies—consequences,” clarifying the relationships among the elements [10]. After the integrative analysis, the core phenomenon was identified as “the process of intercultural learning and communication,” around which the main categories are connected, as shown in Table 3.

|

Axial Coding |

Description |

|

|

Causal Conditions |

Implementation of intercultural communication teaching |

Includes teaching strategies that integrate intercultural content into courses and provide opportunities for intercultural exchange |

|

Students’ personal motivation |

Interest in the target language and culture, and aspirations for overseas developments |

|

|

Core Phenomenon |

The process of intercultural learning and communication |

Characterized by students gradually developing a broader international perspective, becoming more sensitive to and understanding of diverse cultures, and being able to examine themselves and others from a global viewpoint |

|

Contextual Conditions |

Intercultural course environment |

Curriculum design, teaching staff, and peers from diverse cultural backgrounds |

|

Socio-cultural context |

The current degree of globalization, particularly the trend toward educational internationalization |

|

|

Intervening Conditions |

Existing cognitive and attitudinal foundations |

Whether students hold stereotypes and the degree of curiosity toward the target culture |

|

Linguistic foundation and communicative competence |

Foreign language proficiency and previous intercultural experiences |

|

|

Action/Interaction Strategies |

Active intercultural engagement |

Interacting with peers from different cultural backgrounds, completing intercultural projects, and attempting to immerse in the target language culture |

|

Cultural comparison and reflection |

Comparing cultural phenomena and reflecting on misunderstandings or conflicts |

|

|

Application of communication skills and seeking guided feedback |

Adjusting communication approaches based on cultural context, consulting teachers or experienced individuals about intercultural challenges, and improving through feedback |

|

|

Consequences |

Expansion of international perspectives |

Multidimensional development in cultural awareness, attitudes and values, competence, and global consciousness. |

Through axial coding, the above elements were organically connected to depict how intercultural communication teaching influences students’ international perspectives. The core phenomenon, “the process of intercultural learning and communication,” lies at the center of the model. Causal conditions trigger this phenomenon, while contextual and intervening conditions shape its progression. Students employ a series of action strategies to navigate the context and leverage the intervening conditions, ultimately leading to the expansion of their international perspectives.

During selective coding, the core category was refined to “international perspectives development driven by intercultural communication teaching.” Based on participant experiences, the narrative unfolds as follows: In a globalized context, students motivated by personal development engage in intercultural courses and activities. Influenced by their prior knowledge and skills, they actively participate in intercultural interactions, reflecting on cultural differences. This enhances their intercultural competence and broadens their global outlook. The narrative highlights the causal chain between intercultural teaching and the development of international perspectives.

4. Results and discussion

The paradigm relationships culminate in a pathway model (Figure 1) showing how intercultural communication teaching influences the development of international perspectives. Causal conditions, including the implementation of intercultural teaching and students' personal motivation, drive learners into the core process of intercultural learning and communication. Intercultural teaching is the most critical factor, shaping the process and outcomes through multidimensional course design and practical activities [11]. This approach fosters students' understanding and respect for diverse cultures, enhancing their confidence and ability to engage in global affairs.

Contextual factors, such as the internationalization of course content and diverse cultural backgrounds, create an authentic intercultural communication environment. Intervening conditions, like students' prior knowledge, attitudes, and language proficiency, moderate the dynamics of this process. Students with greater cultural sensitivity and open mindsets adapt more effectively and achieve deeper understanding.

Action strategies, including active engagement and reflective cultural comparisons, help students transform theoretical knowledge into practical competence. Through continuous cultural encounters and collaboration, students develop enhanced intercultural communication skills, an open and inclusive mindset, and a critical global perspective.

Based on the findings, this study proposes several suggestions for the practice of intercultural teaching in linguistics courses. First, curriculum design should integrate an internationalized perspective through multicultural case analyses, intercultural simulations, and discussions of international news. This helps students experience cultural differences while learning the language. Second, instructors should develop intercultural awareness and sensitivity, encouraging students to express diverse viewpoints and guiding them through comparative analysis and reflection using interactive strategies like group collaboration and role-playing [12]. This fosters an open dialogue and active participation. Third, a multidimensional evaluation system should be established to assess both language knowledge and intercultural communication skills. Tools could include intercultural exercises, reflective journals, cultural research reports, and project designs, measuring cultural sensitivity, critical thinking and global awareness. Finally, stimulating student motivation is crucial. Designing intercultural activities related to their interests, such as international exchange programs, simulated international meetings, can help students experience the value and enjoyment of intercultural communication, increasing their engagement and initiative in learning.

5. Conclusion

This study employs the classic grounded theory approach, targeting domestic and international university students with intercultural language learning backgrounds. Through in-depth interviews and three-stage coding analysis, it constructed a pathway model illustrating how intercultural communication teaching in university linguistics courses influences the cultivation of students’ international perspectives. The findings reveal that the integration of intercultural communication content and practices into language courses (causal conditions), driven by students’ personal motivation, initiates an active process of intercultural learning and communication (core phenomenon). Throughout this process, contextual factors such as course environment and mediating factors such as students’ prior knowledge and attitudes significantly regulate learning outcomes. By actively participating in intercultural interactions and engaging in cultural comparison and reflection (action strategies), students progressively enhance their cultural cognition, shift their attitudes, and develop intercultural communication skills, ultimately achieving the expansion of their international perspectives (results). This study provides empirical evidence for the internationalization of university language curricula and the cultivation of intercultural competence.

Nevertheless, several limitations remain. For example, the interviews encountered communication difficulties as some participants did not respond in their native language. Additionally, the qualitative research design involved a small sample size, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, due to limited proficiency in methodological application, essential procedures such as saturation testing were not conducted. Future studies should expand the sample size and interview data and perform in-depth comparative analyses to enhance the explanatory power of the conclusions.

References

[1]. Jiang, R., & Zhang, X. (2024). Cross-cultural communication and conflict resolution in tourism. Journal of Social Science Humanities and Literature, 7(4), 6-10.

[2]. Hall, E. T. (1973). The silent language. Anchor.

[3]. Gudykunst, M. H. (1983). Basic Training Design: Approaches to Intercultural Training. In D. Landis, & R. W. Brislin (Eds.), Handbook of Intercultural Training: Issues in Theory and Design (pp. 118-154). Pergamon. https: //doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-027533-8.50011-7.

[4]. Byram, M. (2020). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence: Revisited. Multilingual matters.

[5]. Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of studies in international education, 10(3), 241-266.

[6]. Bi, J. W. (1998). Research on cross-cultural communication and second language teaching. Language Teaching and Research, (1), 10-24.

[7]. Liu, M. (2025). Film media and the cultivation of cross-cultural communication competence: Innovations in English teaching for ethnic preparatory students. Journal of Jilin Provincial Education Institute, 44(05), 15-18. DOI: 10.16083/j.cnki.1671-1580.2025.05.005.

[8]. Kamaz, & Bian, G. Y. (2009). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide for qualitative research. Chongqing University Press, 2009, 3, 58-85.

[9]. Zhou, H. T. (2009). Evin Seidman. Interviews in qualitative research: A guide for educators and social science researchers. Chongqing: Chongqing University Press, 1, 18-19.

[10]. Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage publications.

[11]. Jin, L., & Cortazzi, M. (2016). Teaching and learning intercultural communication: Research in six approaches. In Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 399-415). Routledge.

[12]. Zhao, L. Y. (2024). Research on cross-cultural communication and English teaching: Issues and strategies. Advances in Education, 14, 548. https: //www.hanspub.org/journal/ae https: //doi.org/10.12677/ae.2024.144552

Cite this article

Ouyang,Q. (2025). The Impact of Intercultural Communication Teaching in University Linguistics Courses on the Development of Students’ International Perspectives from a Classical Grounded Theory Perspective: A Case Study of Domestic and International Language Majors. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,111,66-73.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICEIPI 2025 Symposium: Understanding Religious Identity in Educational Contexts

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Jiang, R., & Zhang, X. (2024). Cross-cultural communication and conflict resolution in tourism. Journal of Social Science Humanities and Literature, 7(4), 6-10.

[2]. Hall, E. T. (1973). The silent language. Anchor.

[3]. Gudykunst, M. H. (1983). Basic Training Design: Approaches to Intercultural Training. In D. Landis, & R. W. Brislin (Eds.), Handbook of Intercultural Training: Issues in Theory and Design (pp. 118-154). Pergamon. https: //doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-027533-8.50011-7.

[4]. Byram, M. (2020). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence: Revisited. Multilingual matters.

[5]. Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of studies in international education, 10(3), 241-266.

[6]. Bi, J. W. (1998). Research on cross-cultural communication and second language teaching. Language Teaching and Research, (1), 10-24.

[7]. Liu, M. (2025). Film media and the cultivation of cross-cultural communication competence: Innovations in English teaching for ethnic preparatory students. Journal of Jilin Provincial Education Institute, 44(05), 15-18. DOI: 10.16083/j.cnki.1671-1580.2025.05.005.

[8]. Kamaz, & Bian, G. Y. (2009). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide for qualitative research. Chongqing University Press, 2009, 3, 58-85.

[9]. Zhou, H. T. (2009). Evin Seidman. Interviews in qualitative research: A guide for educators and social science researchers. Chongqing: Chongqing University Press, 1, 18-19.

[10]. Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage publications.

[11]. Jin, L., & Cortazzi, M. (2016). Teaching and learning intercultural communication: Research in six approaches. In Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 399-415). Routledge.

[12]. Zhao, L. Y. (2024). Research on cross-cultural communication and English teaching: Issues and strategies. Advances in Education, 14, 548. https: //www.hanspub.org/journal/ae https: //doi.org/10.12677/ae.2024.144552