1. Introduction

Political party competition in Singapore presents unique structural features. Despite the convenience of party registration and the legal existence of multiple parties, only a few opposition parties, such as the Workers' Party (WP), continue to contest elections.

The main opposition parties have failed to offer a coherent ideological alternative and in particular have avoided challenging the People’s Action Party (PAP)’s core value of pragmatism and meritocracy that rationalizes the socio-political hierarchy built up over the past few decades [1]. making the opposites to nitpick rather than shake the political legitimacy that regards the government as the exclusive domain of experts [2,3]. Opposition parties blame this predicament on systemic obstacles. Both scholars and opposition parties, however, neglect the perspective of political brand.

Some scholars believed that Valence brand and Policy brand are the core elements of Party brand [4-6]. It is also believed that party brands should achieve the two goals of identification and differentiation [7]. The theory that integrates these two aspects provides us with a new perspective to understand the subjectivity of opposition parties. PAP's high-performance legitimacy, based on past economic and social achievements, makes it challenging for weak opposition parties to compete. Opposition parties have failed to develop coherent policy alternatives or distinct brand differentiation, increasing voters' cognitive costs [6,8]. This lack of differentiation blurs the distinction between opposition coalitions and PAP. WP has gradually built an image as a professional supervisor and constructive opposition through parliamentary inquiries and community service [9,11]. However, associating with smaller parties could introduce uncertainty, deterring median voters from supporting such alliances. Additionally, voters view party support as part of their social identity [12,13], and transforming this identity during coalition formation incurs psychological costs, which is difficult within Singapore's short election cycles. Consequently, opposition parties often prefer maintaining separate identities. While WP and other minor parties share a general anti-PAP stance, significant differences in grassroots services and social welfare hinder compatibility. WP avoids diluting its brand [9] by distancing itself from smaller parties, preserving its image as professional, responsible, rational, and constructive.

This paper asks why the Workers' Party, despite being the most electorally salient opposition actor with clear collective incentives to coordinate, persistently avoids formal alliances with smaller opposition parties. This study argues the answer lies in the dual logic of political branding: WP has deliberately cultivated a distinctive valence image—professional, responsible, rational, and constructive—through parliamentary oversight and community engagement, which serves both as a cognitive shortcut and a credibility anchor for voters. Coalition with smaller or less compatible parties, however, risks diluting that identity, injects uncertainty for median voters, and imposes psychological costs because party support is partly internalized as social identity. These brand-related dynamics create endogenous strategic constraints that discourage cooperation even when structural benefits from alliance exist. This paper reframes political branding as more than a voter heuristic: it is an internal brake on opposition coalition-building. Using Singapore, it demonstrates how deliberate brand management collides with structural incentives to entrench fragmentation under dominant-party rule.

2. Literature review

There is growing scholarly interest in how voters learn about political parties and make voting decisions based on that information. As an important topic in political marketing research, "political brand" or “party brand” has been gradually used to study the relationship between political parties and civil society in recent years [4,14]. Scholars argue that political parties are brands because they act as brands to consumers [9,18,22]. Voters, meanwhile, attach meaning to the names and symbols of political parties over time, allowing them to differentiate and vote for one party over another at an election.

Nielsen argued that political brands have two core values: identification and differentiation [7]. The former is the premise of political brand building, and political parties should make them identifiable in the hearts of voters through stable labels, symbols and styles. From this we obtain a minimal definition of political branding:

A political brand is political representations that are located in a pattern, which can be identified and differentiated from other political representations [7].

This conceptualization uses the concept of business branding: voters' knowledge of politicians' names, the "brand value" of parties, specific policies, etc., is largely assumed to be accurate and consistent among voters [23]. But this is not to say that the electorate is uniformly knowledgeable about political brands. For countries where voting is not compulsory, low voter participation has been a normal feature of Western elections in recent years. As a result, many voters are less aware of political brands and also feel that there are not many benefits from voting [23]. For them, the political brand is less influential. By contrast, politically engaged and strongly partisan voters are likely to be far more swayed by strategic political branding. To some extent, this theory inherits the voter simplification theory of Downs [24].

From the perspective of voters (consumers), as a kind of symbolic cognitive structure, the relevant information of a party brand is remembered by voters in ordinary times, and the information related to a specific party will be activated in the election, so that voters can make judgments and choices without in-depth understanding of all the policy details of candidates [23]. Scholars pay more attention to the influence of voters' brand identification and trust in political parties on voting behavior, and voters with strong partisan identification are often more sensitive to party brands [13,23,25,26].

Political parties, on the other hand, share many similarities with company managers, paying more attention to how to actively build and maintain product brands. Political brands are regarded as strategic assets, which requires clear Identification and Differentiation [7]. Political parties gradually shape voter cognition through clear brand identity (such as platform content, party values, party emblem, leader image, etc.) [27]. As operators, political parties attach more importance to the congruence between political propaganda and their internal values, and only by showing the sincerity and authenticity of political parties can they gain the trust of voters [25]. In short, the consumer perspective focuses on how brands are perceived by voters, while the manager perspective focuses on how political parties construct and enforce their brand image.

Scholars began to apply the concept of marketing to the field of political research at the end of the 20th century [8,25,28,30]. Needham, for instance, compared the voting behavior of voters with the product choice behavior of consumers [25]. Since then, the research on party brand usually starts from the two directions of voters and political parties: Reeves and Scammell examined the strategic balance between political parties driven by ideology and driven by voters [9,27]. Smith and French combined political psychology with consumer psychology to elaborate on the cognitive mechanism of voters on party brands [23]. Nielsen focused on the influencing factors of political parties’ choice of political propaganda strategies [7].

There is a debate among scholars about whether the political brands of political parties are stable. Some scholars believe that party brands are stable and consist of long-term interrelated nodes [23,31]. However, some scholars believe that political brands are unstable, and political parties will frequently change their positions since “...branding is underpinned by the insight that these images are highly vulnerable, constantly changing, and rarely under complete control” [32]. This divergence is due to differences in understanding the interaction mechanism of the three core elements of political branding: political party, leaders and policy.

Parties, party leaders and policy design are three key elements of political branding [7,23], with a clear division and frequent interaction between elements: a party functions as a brand, with politicians as its visible feature and using policy as the core service product [33].

Party leaders are the tangible embodiment of brands, and their personal charm can deliver brand value to voters on behalf of the party [25]. For example, the critical role of leaders in brand communication is exemplified by the fact that voters are increasingly attracted to political parties (even as much as to policies) by their leaders. Moreover, in the era of “candidate-centered” elections, highlighting a leader's own brand image may be more effective in the heat of political party contests.

Policy issues are the flagship product that parties offer voters; they attract support and amplify brand power. A party’s enduring fidelity to—and consistent messaging around—its core values and platform ultimately forges the credibility and coherence of its political brand [23]. Political parties need to ensure that policy communications are consistent with their brand promises to better sustain the party-voter relationship. However, in many democratic countries, mainstream parties converge on most policy positions, and small policy differences between parties reduce the differentiation among different political brands.

As the institutional carrier of the brand, the party organization's internal organizational structure, the relationship among elites, and the historical culture of party development provide the foundation for party brand building. Reeves et al. pointed out that with the trend of ideological dilution, party organizations often need to strike a balance between short-term performance improvement to cater to voters and long-term adherence to party principles [27]. Party organizations are also responsible for integrating party members and local cadres at all levels; for example, the People's Action Party of Singapore embeds party organizations into the society and conveys a unified brand image to grassroots voters through a top-down, vertical and efficient organizational system [34]. In other words, the party organization enables political parties to have both institutional stability and continuous transmission of values, which is similar to the role of corporate culture in corporate brand building.

This paper argues that political brands refer to the public's overall perception of a political organization or individual. It reflects the impression or image people associate with a politician, party, or country. Political branding helps parties or candidates adjust their reputation, build identity, and establish trust with voters. It also enables voters to quickly understand a party's or candidate's claims and differentiate them from competitors.

3. Theoretical framework

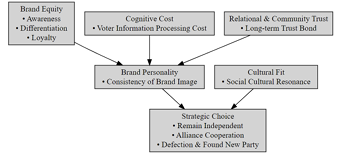

Referring to Nielsen [7], Newman and Pich [6] and Butler and Powell’s [4] research on party brand, we construct the mechanism of party brand building as shown in Figure 1.

Political brand equity includes party identification, differentiation and voter loyalty. When a political party has successfully established a positive association with the party through long-term parliamentary debates, community services, and continuous publicity, voters form a party brand image in their minds. But any change that could shake or blur that image, such as a hasty-to-hasty-alliance, could lead to "brand dilution", clouding voters' perception of its original strengths and losing votes.

Because of the uneven distribution of resources [35,36], it is not easy for small parties to build clear political brands. If a party is in coalition with other small parties, voters must expend extra effort to discern the arguments and which issues come from which side, which raises the cognitive cost of voters. Once the cognitive cost exceeds its mental threshold, they are more inclined to vote for a single party with a clear memory or to abstain altogether.

In addition, the long-term trust built up between a party and its grassroots supporters through community activities and face-to-face visits will be gradually diluted in the process of alliance due to factors such as lack of tacit understanding between different parties or inconsistent values and operating methods, thus weakening the party's original support base.

In this view, parties must make trade-offs when deciding whether to cooperate with other parties. If maintaining independence can preserve the brand equity to the greatest extent, reduce the cognitive cost of voters, maintain the existing trust, and maintain the brand personality and cultural fit, it is not suitable to join forces with other parties in the short term. On the contrary, when the alliance with other parties brings certain benefits in terms of resources, but the cost of brand dilution, cognitive confusion, trust loss and cultural conflict is too high, political parties will choose to remain independent to build differentiated brands and regain "clear identification" and "high recognition" in the hearts of voters.

The existing research on party politics in Singapore mainly focuses on the dominant position of the ruling party, the People's Action Party, under the hegemonic party system [36,39], or analyzes the power consolidation mechanism of the People's Action Party (PAP) from the perspective of the electoral system [40] and the uneven distribution of political resources [1,46]. In fact, the ideological differences among Singapore's opposition parties are actually very weak, and there have been many attempts to form an opposition coalition in history, but the coalition is often fleeting. The Workers' Party (WP), the most powerful opposition party, has long been resistant to alliances with other opposition parties. This paper aims to illustrate the dilemma of opposition parties in Singapore through the framework of political branding above: Why is it difficult for opposition parties in Singapore to achieve long-term, stable cooperation? In particular, why is the Workers' Party reluctant to cooperate with other opposition parties?

4. GE2025 as an example

In 2023, The People's Alliance for Reform (PAR), formed by the People's Power Party (PPP), the People’s Voice (PV), the Reform Party (RP) and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), and The Coalition, an informal alliance of the Red Dot United Party (RDU), the Singapore People's Party (SPP) and the Singapore United Party (SUP), were established successively. However, the good times did not last long. Before the end of April this year, the People's Power Party withdrew from the PAR on the grounds that "strategic differences could not be ironed out", and the Red Dot Party also announced its departure from the original alliance due to dissatisfaction with the alliance's decision to run in the Sembawang group representation constituency (GRC). The vitality of the two parties’ alliance was badly damaged. In addition to the disbanded coalition, the PAR failed to hold the constituency base in this election. Although some opposition parties hope to build a coalition again and break through the limits of the so-called “power to balance” after the election, such proposals have always been rebuffed by the Workers’ Party [47].

The political brand theory properly explains one of the important reasons why WP does not cooperate with other opposition parties from the perspective of subjectivity, that is, the WP’s strategic choice of its strategic layout at the level of identification and differentiation.

With pragmatic oversight as its brand positioning, WP plays the role of a "constructive opposition" through rational questioning and constructive questioning in Parliament [11,49]. By observing the contents of the policy platforms of the participating political parties shown in Table 1 below, it is not difficult to find that, unlike some small opposition parties, which focus too much on abstract concepts such as human rights and democracy, the Workers' Party focuses more on issues such as income, housing, medical care and education, which are the daily concerns of voters, and can reflect the core ideas of the party in the specific policy platforms.

|

Political Party |

PAP |

PSP |

WP |

SDP |

PPP |

RDU |

SDA |

SPP |

PAR* |

|

|

Living expenses |

Providing subsidies such as community vouchers; Strengthen assistance to low-income families and the elderly |

Set rental guidance prices for commercial properties |

Opposition to GST (consumption tax) increase; Introduce minimum wage |

Abolish GST |

Provide monthly allowance for children from low-income families |

Provide basic income guarantees for Singaporeans |

Ensuring that the basic needs of low-income workers and families are met |

Ensuring that the basic needs of low-income workers and families are met |

||

| Table 1. (continued) | ||||||||||

|

Housing |

Plans to build 50,000 new HDB flats over the next three years to provide more public housing options for high-income couples and singles; Renew older HDB blocks through the Voluntary Early Redevelopment Scheme. |

Land costs are not factored into HDB prices; Provide quality rental housing for young people |

Provide HDB flats according to the financial pressure of buyers |

Reevaluate housing policy |

Reevaluate housing policy |

A housing replacement plan is proposed to re-evaluate land costs and housing pricing mechanisms |

Reevaluate housing policy |

Provide preferential housing policies and subsidies for two-child families and singletons |

||

|

Plank and Platform |

Employment and Economic growth |

Supporting businesses to cope with rising costs with tax rebates and the Progressive Wage Credit Scheme; Invest in transport, digital infrastructure and clean energy |

Removing non-competition clauses for retrenched employees and enforcing statutory redundancy benefits; Shortening working hours; Increase paid holidays and public holidays; Provide equal parental leave to parents |

Abolishing the statutory retirement age; Allowing CPF members to co-invest their savings with the Government Investment Corporation (GIC); Enhancing leadership support for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) |

Implement the minimal wage system |

Strengthened protection for local workers |

Equal employment opportunity; Strengthened protection for local workers |

Strengthened protection for local workers |

Shorten the duration of National Service (NS) and increase the national service allowance |

No campaign platform was released. The coalition used to focus on consumption tax and price increases, public housing prices, employment policy, and domestic democracy |

|

Social security and inclusiveness |

Raising the re-employment age and increasing CPF contributions; Provide special services for skill improvement |

Centralize drug procurement to reduce costs |

introduce unemployment insurance |

More inclusive social policies |

More supportive policies for families |

More inclusive social policies |

More inclusive social policies |

|||

| Table 1. (continued) | ||||||||||

|

Education and Skills |

Reduce the cost of preschool education and increase subsidies for child care. |

Equity in education; Reforming the education system to reduce stress; Promote artificial intelligence skills training |

Educational equality; Reforming the education system to reduce stress; Promote artificial intelligence skills training |

Reform educational system, focusing on educational equality |

Reform educational system, focusing on educational equality |

Reform educational system, focusing on educational equality |

Educational equality |

Reduce the burden of education |

||

|

Political institutions and Governance |

Emphasis on team renewal and adherence to the original intention |

Review Singapore's economic cooperation with foreign countries to protect local workers and ensure fair competition |

Repeal the Internal Security Act; Emphasize freedom of information |

Strengthen democratic institutions and ensure government accountability |

Change the current FPTP electoral system to PR system |

Build digital platforms to work with other opposition parties to propose policy alternatives |

More democracy |

Strengthen parliamentary oversight and accountability |

||

The WP has presented itself as a different party brand from other opposition parties in terms of party building, parliamentary performance and grassroots services, namely an image of working hard in constituencies and working with voters to solve problems [51] rather than "opposing for the sake of opposing".

In terms of parliamentary performance, the WP’s MPs, represented by Low Thia Khiang, Sylvia Lim, Pritam Singh Khaira and others [51], have actively performed their oversight duties in Parliament and participated in important policy debates, and through strict internal control and party discipline rectification to maintain a relatively clean, professional parliamentary group image.

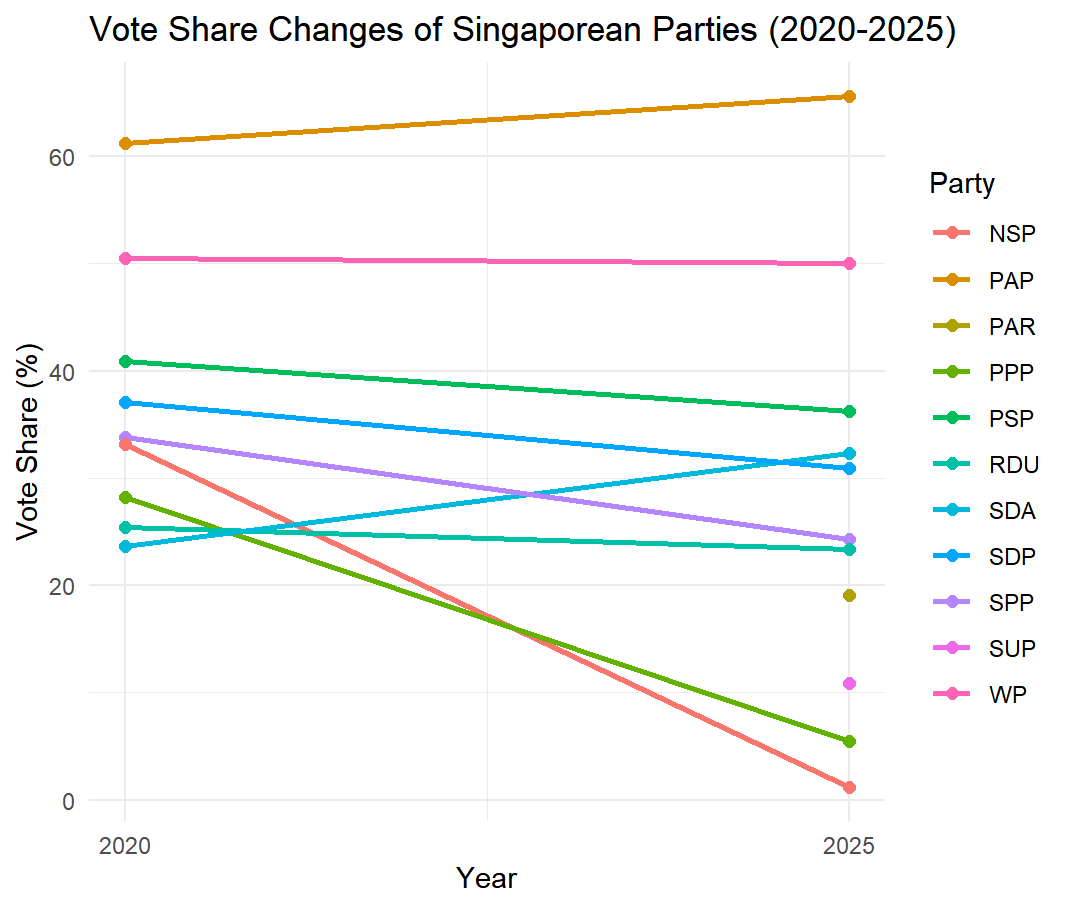

From the perspective of grassroots services, WP always insists on serving all residents. Many small parties appear only during the five-yearly election cycle and then disappear, with no long-term plan to serve constituencies [52]. They pay lip service to their constituents' voices in Congress, but forget that the basic purpose of running is to help and serve them. In contrast to the mode of some small parties, the Central Executive Committee of WP and its volunteer teams continue to carry out community service throughout the year to ensure that voters can get help at any time. The "relational trust" formed by such long-term interaction makes voters regard their support for the Workers' Party as part of their partisan identity [13]. Through the party organization's contact with community organizations during the election campaign and daily, WP has demonstrated its pragmatic and rational valence and policy brand to residents, enabling more views to be entered into the Parliament [36,44,53]. Since its historic breakthrough in the 2011 general election, the WP has relied on a growing network of volunteers and party members to consolidate its vote base in Alyouni, Seng Kong and Hougang by running Town councils, and conducting routine home visits and community services. Moreover, WP also won two NCMP (abbreviation for non-constituency member of parliament) seats, and won more than 40% of the vote in all the contested districts this year, making it a strong opponent of the PAP [52].

The WP has gained considerable brand equity [51,54], and its brand personality has been widely known among voters compared with other opposition parties. So, voters can vote without incurring significant cognitive costs to distinguish them from the ruling party and other small parties. It is argued that political parties would take the initiative to avoid any behavior that might damage the party valence brand, which is a rational strategic choice no matter if in terms of short-term electoral interests or long-term development [4]. If we rashly join forces with other opposition parties, especially with some newly established small parties that are slightly bold in their platform and lack the ability to mobilize the grassroots, we may dilute or even damage the professional, pragmatic, rational and moderate image of the Workers' Party accumulated in the minds of voters over the years. On the contrary, we may make voters see the Workers' Party as a kind of mixed-up opposition coalition. Once the alliance is formed, the possible free-riding behavior of minor parties is likely to be rapidly amplified within a very short election cycle, and then affect voters' trust in the Workers' Party, which is undoubtedly a huge impact on the brand equity accumulated by the Workers' Party over the years.

Also, brand differentiation is particularly critical during campaign periods of misinformation, as voters are more likely to vote for parties that can accurately anticipate their behavior and demands amid a flood of campaign information [7]. Based on the deep insight into brand identification and brand differentiation, WP is well aware that after the coalition with other minor parties, it will be forced to share the brand personality elements of the other party, thus weakening its "pragmatic and constructive" label in the minds of voters.

Lastly, there is a fundamental conflict between WP and other opposition parties over brand compatibility [54]. When parties consider forming electoral alliances, they assess not only the stand-alone value of their brands, but also whether their brand images can coexist without confusing or weakening voter perceptions. In other words, the compatibility of two or more party brands depends on whether their respective values, issue focus and leadership images overlap enough to form a coherent joint image while remaining sufficiently different to retain the core characteristics of each party. The WP [55] has deeply blended its roots with multiethnic composition, and is committed to Asian values. In contrast, parties such as the SPP and the SDP excessively pursue the protection of specific ethnic groups and the expansion of social welfare, which is different from the progressive and pragmatic culture of the WP. Even if parties unite, there will be cracks in core values, and voters will pay an implicit psychological cost. Therefore, it can be assumed that the WP may not achieve cultural fit with other minor parties in the short term.

It is thus argued that the Workers' Party has gradually formed the image of a pragmatic and rational opposition party through the construction of parliamentary supervision, community service and the basic ability of party organization [34], which has formed a brand differentiation separation from other "immature" small parties.

5. Conclusion

This paper deepens the understanding of opposition fragmentation under hegemonic-party circumstances by identifying political branding as an endogenous strategic constraint on coalition formation. Through a detailed case analysis of the Workers' Party in Singapore, it is demonstrated that its meticulously crafted valence brand, which is founded on professionalism, responsibility, rationality, and constructive oversight, serves a dual function. On one hand, it acts as a credibility-boosting heuristic that reduces voter cognitive costs. On the other hand, it creates internal disincentives for cooperation. This is because allying with smaller or less compatible parties jeopardizes brand purity, introduces uncertainty for median voters, and incurs identity-reconfiguration costs for constituents who have partially internalized party support as part of their social identity.

These branding dynamics thus contribute to explaining why, despite the evident collective advantages of coordination, opposition coalitions remain difficult to achieve and fragmentation persists. The conceptual contribution lies in reconceptualizing political branding not merely as an informational shortcut for voters but as an actor-level constraint that shapes strategic choices regarding cooperation. Empirically, the Singapore case exemplifies how identity management interacts with structural incentives to result in persistent disunity among opposition actors, thereby complicating conventional institutional or regime-centered explanations.

It should also be noted that the study has several limitations.The branding mechanism is primarily inferred from behavioral patterns and secondary evidence; direct empirical validation—through voter surveys, experiments, or process-tracing of identity shifts—is needed to establish causal depth. Moreover, the generalizability of the mechanism beyond the Singaporean context remains to be tested. Future research can strengthen and extend this framework by measuring voter-level identity and perceived dilution costs via surveys or conjoint experiments; tracing inter-party signaling and compatibility perceptions using network or discourse analysis; and conducting systematic comparative studies across dominant-party systems to assess how the tension vary with electoral timing, regime openness, and opposition fragmentation structures. These extensions would both bolster causal inference and situate the branding-induced fragmentation mechanism within broader comparative theory.

References

[1]. Rodan, Garry. (2004) Transparency and authoritarian rule in Southeast Asia: Singapore and Malaysia. Routledge.

[2]. Chua, Beng-Huat. (2002) Communitarian ideology and democracy in Singapore. Routledge.

[3]. Hwee, Yeo Lay. (2002) Electoral politics in Singapore. Electoral politics in southeast and east Asia, 203: 217.

[4]. Butler, Daniel M., and Eleanor Neff Powell. (2014) Understanding the party brand: experimental evidence on the role of valence. The Journal of Politics 76, no. 2, pp. 492-505.

[5]. Pich, Christopher, and Bruce I. Newman. (2020) Evolution of political branding: Typologies, diverse settings and future research. Journal of Political Marketing 19, no. 1-2, pp. 3-14.

[6]. Pich, Christopher, and Bruce I. Newman, eds. (2020) Political branding: More than parties, leaders and policies. Routledge.

[7]. Winther Nielsen, Sigge. (2017) On political brands: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Political Marketing 16, no. 2, pp.118-146.

[8]. Harris, Phil, and Andrew Lock. (2010) “Mind the gap”: the rise of political marketing and a perspective on its future agenda. European Journal of Marketing 44, no. 3/4, pp.297-307.

[9]. Scammell, Margaret. (2015) Politics and image: the conceptual value of branding. Journal of political marketing 14, no. 1-2, pp.7-18.

[10]. Abdullah, Walid Jumblatt. (2017) Bringing ideology in: Differing oppositional challenges to hegemony in Singapore and Malaysia. Government and Opposition 52, no. 3, pp.483-510.

[11]. Zhengtao Lu. (2023) Shaping the “Constructive Opposition Party” in Singapore: A Perspective of Nation - Building. Comparative Political Studies. no. 1, pp.246-261.

[12]. Green, Jane. (2007) When voters and parties agree: Valence issues and party competition. Political Studies 55, no. 3, pp.629-655.

[13]. Green, Donald P., Bradley Palmquist, and Eric Schickler. (2004) Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. Yale University Press.

[14]. Newman, Bruce I., and Jagdish N. Sheth. (1985) A model of primary voter behavior. Journal of Consumer Research 12, no. 2, pp.178-187.

[15]. Burton, Scot, and Richard G. Netemeyer. (1992) The effect of enduring, situational, and response involvement on preference stability in the context of voting behavior. Psychology & Marketing 9, no. 2, pp. 143-156.

[16]. Newman, Bruce I. (1999) The mass marketing of politics: Democracy in an age of manufactured images. Sage Publications.

[17]. Cwalina, Wojciech, Andrzej Falkowski, and Bruce I. (2015) Newman. Political Marketing: Theoretical and Strategic Foundations. Routledge.

[18]. Ahmed, Mirza Ashfaq, Suleman Aziz Lodhi, and Zahoor Ahmad. (2017) Political brand equity model: The integration of political brands in voter choice. Journal of Political Marketing 16, no. 2, pp.147-179.

[19]. Billard, Thomas J. (2018) Citizen typography and political brands in the 2016 US presidential election campaign. Marketing Theory 18, no. 3, pp. 421-431.

[20]. Meyerrose, Anna M. (2018) It is all about value: How domestic party brands influence voting patterns in the European Parliament. Governance 31, no. 4, pp.625-642.

[21]. Speed, Richard, Patrick Butler, and Neil Collins. (2015) Human branding in political marketing: Applying contemporary branding thought to political parties and their leaders. Journal of political marketing 14, no. 1-2, pp. 129-151.

[22]. Smith, Gareth. (2009) Conceptualizing and testing brand personality in British politics. Journal of political marketing 8, no. 3, pp. 209-232.

[23]. Smith, Gareth, and Alan French. (2009) The political brand: A consumer perspective. Marketing theory 9, no. 2, pp.209-226.

[24]. Downs, Anthony. (1957) An economic theory of political action in a democracy. Journal of political economy 65, no. 2, pp. 135-150.

[25]. Needham, Catherine. (2006) Brands and political loyalty. Journal of Brand Management 13, pp. 178-187.

[26]. Mccarty, Nolan, Paul Pierson, and Eric Schickler. (2025) Partisan Nation: The Dangerous New Logic of American Politics in a Nationalized Era.

[27]. Reeves, Peter, Leslie de Chernatony, and Marylyn Carrigan. (2006) Building a political brand: Ideology or voter-driven strategy. Journal of Brand Management 13, no. 6, pp. 418-428.

[28]. Achrol, Ravi S., and Philip Kotler. (1999) Marketing in the network economy. Journal of marketing 63, no. 4_suppl1, pp.146-163.

[29]. Lees‐Marshment, Jennifer. (2001) The marriage of politics and marketing. Political studies 49, no. 4, pp. 692-713.

[30]. Schneider, Helmut. (2004) Branding in politics—manifestations, relevance and identity-oriented management. Journal of Political Marketing 3, no. 3, pp. 41-67.

[31]. Lees-Marshment, Jennifer. (2009) Global political marketing." In Global political marketing, Routledge, pp. 19-33.

[32]. Scammell, Margaret. (2007) Political brands and consumer citizens: The rebranding of Tony Blair. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 611, no. 1, pp. 176-192.

[33]. Henneberg, Stephan C., and Nicholas J. O'shaughnessy. (2007) Theory and concept development in political marketing: Issues and an agenda. Journal of political marketing 6, no. 2-3, pp. 5-31.

[34]. Qingjie Zeng. (2024) Party origins, party infrastructural strength, and governance outcomes. British Journal of Political Science 54, no. 3, pp. 667-692.

[35]. Greene, Kenneth F. (2007) Why dominant parties lose: Mexico's democratization in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press.

[36]. Mutalib, Hussin. (2000) Illiberal democracy and the future of opposition in Singapore. Third World Quarterly 21, no. 2, pp. 313-342.

[37]. Grofman, Bernard. (2016) Perspectives on the comparative study of electoral systems. Annual Review of Political Science 19, no. 1: 523-540.

[38]. Wong, Benjamin. (2013) Political meritocracy in Singapore. The East Asian challenge for democracy: Political meritocracy in comparative perspective, pp.288-313.

[39]. Tan, Netina, and Bernard Grofman. (2018) Electoral rules and manufacturing legislative supermajority: evidence from Singapore. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 56, no. 3, pp.273-297.

[40]. Rodan, Garry. (2013) State—society relations and political opposition in Singapore. In Political oppositions in industrialising Asia, Routledge, pp. 78-103.

[41]. Magaloni, Beatriz. (2008) Credible power-sharing and the longevity of authoritarian rule. Comparative political studies 41, no. 4-5, pp.715-741.

[42]. Hicken, Allen. (2009) Building party systems in developing democracies. Cambridge University Press.

[43]. Tan, Eugene KB. (2012) SINGAPORE: Transitioning to a "New Normal" in a Post-Lee Kuan Yew Era. Southeast asian affairs 2012, no. 1, pp. 265-282.

[44]. Ortmann, Stephan. (2011) Singapore: Authoritarian but newly competitive. Journal of Democracy 22, no. 4, pp. 153-164.

[45]. Tan, Netina. (2013) Manipulating electoral laws in Singapore. Electoral studies 32, no. 4, pp.632-643.

[46]. Rodan, Garry. (2008) Singapore “exceptionalism”? Authoritarian rule and state transformation. In Political Transitions in Dominant Party Systems, Routledge, pp. 247-267.

[47]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) Red Dot United hopes to work with other parties to build a shadow government and shared platform, May 24. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/news/singapore/story20250524-6463937

[48]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) GE2025 visualization: Interactive statistics, party manifestos, election analysis, and live results, May. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/specials/singapore-general-election-2025/visualization

[49]. Jingfeng Sun. (2006) The People’s Action Party and Opposition Parties in Singapore. Academics. no. 2, pp.289 - 293.

[50]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) [GE2025] Party Manifesto Comparison – Partisan policy platforms juxtaposed on the GE2025 live dashboard. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/specials/singapore-general-election-2025/party-manifesto

[51]. James, Kieran, Bligh Grant, and Jenny Leung. (2013) Oppositional Grassroots Activism in PAP Singapore. Available at SSRN 2290028.

[52]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) [GE2025] Ou Jincai: Insights from the 2025 Singapore General Election, May 6. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/forum/views/story20250506-6295555

[53]. Ortmann, Stephan. (2009) Singapore: The politics of inventing national identity. Journal of current Southeast Asian affairs 28, no. 4, pp. 23-46.

[54]. Phipps, Marcus, Jan Brace‐Govan, and Colin Jevons. (2010) The duality of political brand equity. European Journal of Marketing 44, no. 3/4, pp. 496-514.

[55]. 8world. (2025) Leong Mun Wai: I considered my parliamentary question reasonable despite being accused of racist remarks by Shanmugam, February 7. https: //www.8world.com/singapore/leong-mun-wai-response-on-being-called-out-by-shanmugam-for-racist-remarks-2699181

[56]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) [GE2025] Cheng Soon Guan apologises over Yuen Kee Jun’s gaffe to all Singaporeans—especially the Indian community, April 27. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/realtime/singapore/story20250427-6253573

[57]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) [GE2025] Singaporeans’ identity comes first – Masagos urges not to use race and religion as political tools, April 26. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/realtime/singapore/story20250426-6248934

[58]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) [GE2025] Workers’ Party: Firmly uphold the principle of separation of religion and politics in our country, April 27. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/news/singapore/story20250427-6250096

Cite this article

Du,Z. (2025). Political Brand and the Opposition’s Disunity: An Explanation of WP’s Reluctance to Ally. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,112,25-36.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICILLP 2025 Symposium: Digital Governance: Inter-Firm Coopetition and Legal Frameworks for Sustainability

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Rodan, Garry. (2004) Transparency and authoritarian rule in Southeast Asia: Singapore and Malaysia. Routledge.

[2]. Chua, Beng-Huat. (2002) Communitarian ideology and democracy in Singapore. Routledge.

[3]. Hwee, Yeo Lay. (2002) Electoral politics in Singapore. Electoral politics in southeast and east Asia, 203: 217.

[4]. Butler, Daniel M., and Eleanor Neff Powell. (2014) Understanding the party brand: experimental evidence on the role of valence. The Journal of Politics 76, no. 2, pp. 492-505.

[5]. Pich, Christopher, and Bruce I. Newman. (2020) Evolution of political branding: Typologies, diverse settings and future research. Journal of Political Marketing 19, no. 1-2, pp. 3-14.

[6]. Pich, Christopher, and Bruce I. Newman, eds. (2020) Political branding: More than parties, leaders and policies. Routledge.

[7]. Winther Nielsen, Sigge. (2017) On political brands: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Political Marketing 16, no. 2, pp.118-146.

[8]. Harris, Phil, and Andrew Lock. (2010) “Mind the gap”: the rise of political marketing and a perspective on its future agenda. European Journal of Marketing 44, no. 3/4, pp.297-307.

[9]. Scammell, Margaret. (2015) Politics and image: the conceptual value of branding. Journal of political marketing 14, no. 1-2, pp.7-18.

[10]. Abdullah, Walid Jumblatt. (2017) Bringing ideology in: Differing oppositional challenges to hegemony in Singapore and Malaysia. Government and Opposition 52, no. 3, pp.483-510.

[11]. Zhengtao Lu. (2023) Shaping the “Constructive Opposition Party” in Singapore: A Perspective of Nation - Building. Comparative Political Studies. no. 1, pp.246-261.

[12]. Green, Jane. (2007) When voters and parties agree: Valence issues and party competition. Political Studies 55, no. 3, pp.629-655.

[13]. Green, Donald P., Bradley Palmquist, and Eric Schickler. (2004) Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. Yale University Press.

[14]. Newman, Bruce I., and Jagdish N. Sheth. (1985) A model of primary voter behavior. Journal of Consumer Research 12, no. 2, pp.178-187.

[15]. Burton, Scot, and Richard G. Netemeyer. (1992) The effect of enduring, situational, and response involvement on preference stability in the context of voting behavior. Psychology & Marketing 9, no. 2, pp. 143-156.

[16]. Newman, Bruce I. (1999) The mass marketing of politics: Democracy in an age of manufactured images. Sage Publications.

[17]. Cwalina, Wojciech, Andrzej Falkowski, and Bruce I. (2015) Newman. Political Marketing: Theoretical and Strategic Foundations. Routledge.

[18]. Ahmed, Mirza Ashfaq, Suleman Aziz Lodhi, and Zahoor Ahmad. (2017) Political brand equity model: The integration of political brands in voter choice. Journal of Political Marketing 16, no. 2, pp.147-179.

[19]. Billard, Thomas J. (2018) Citizen typography and political brands in the 2016 US presidential election campaign. Marketing Theory 18, no. 3, pp. 421-431.

[20]. Meyerrose, Anna M. (2018) It is all about value: How domestic party brands influence voting patterns in the European Parliament. Governance 31, no. 4, pp.625-642.

[21]. Speed, Richard, Patrick Butler, and Neil Collins. (2015) Human branding in political marketing: Applying contemporary branding thought to political parties and their leaders. Journal of political marketing 14, no. 1-2, pp. 129-151.

[22]. Smith, Gareth. (2009) Conceptualizing and testing brand personality in British politics. Journal of political marketing 8, no. 3, pp. 209-232.

[23]. Smith, Gareth, and Alan French. (2009) The political brand: A consumer perspective. Marketing theory 9, no. 2, pp.209-226.

[24]. Downs, Anthony. (1957) An economic theory of political action in a democracy. Journal of political economy 65, no. 2, pp. 135-150.

[25]. Needham, Catherine. (2006) Brands and political loyalty. Journal of Brand Management 13, pp. 178-187.

[26]. Mccarty, Nolan, Paul Pierson, and Eric Schickler. (2025) Partisan Nation: The Dangerous New Logic of American Politics in a Nationalized Era.

[27]. Reeves, Peter, Leslie de Chernatony, and Marylyn Carrigan. (2006) Building a political brand: Ideology or voter-driven strategy. Journal of Brand Management 13, no. 6, pp. 418-428.

[28]. Achrol, Ravi S., and Philip Kotler. (1999) Marketing in the network economy. Journal of marketing 63, no. 4_suppl1, pp.146-163.

[29]. Lees‐Marshment, Jennifer. (2001) The marriage of politics and marketing. Political studies 49, no. 4, pp. 692-713.

[30]. Schneider, Helmut. (2004) Branding in politics—manifestations, relevance and identity-oriented management. Journal of Political Marketing 3, no. 3, pp. 41-67.

[31]. Lees-Marshment, Jennifer. (2009) Global political marketing." In Global political marketing, Routledge, pp. 19-33.

[32]. Scammell, Margaret. (2007) Political brands and consumer citizens: The rebranding of Tony Blair. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 611, no. 1, pp. 176-192.

[33]. Henneberg, Stephan C., and Nicholas J. O'shaughnessy. (2007) Theory and concept development in political marketing: Issues and an agenda. Journal of political marketing 6, no. 2-3, pp. 5-31.

[34]. Qingjie Zeng. (2024) Party origins, party infrastructural strength, and governance outcomes. British Journal of Political Science 54, no. 3, pp. 667-692.

[35]. Greene, Kenneth F. (2007) Why dominant parties lose: Mexico's democratization in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press.

[36]. Mutalib, Hussin. (2000) Illiberal democracy and the future of opposition in Singapore. Third World Quarterly 21, no. 2, pp. 313-342.

[37]. Grofman, Bernard. (2016) Perspectives on the comparative study of electoral systems. Annual Review of Political Science 19, no. 1: 523-540.

[38]. Wong, Benjamin. (2013) Political meritocracy in Singapore. The East Asian challenge for democracy: Political meritocracy in comparative perspective, pp.288-313.

[39]. Tan, Netina, and Bernard Grofman. (2018) Electoral rules and manufacturing legislative supermajority: evidence from Singapore. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 56, no. 3, pp.273-297.

[40]. Rodan, Garry. (2013) State—society relations and political opposition in Singapore. In Political oppositions in industrialising Asia, Routledge, pp. 78-103.

[41]. Magaloni, Beatriz. (2008) Credible power-sharing and the longevity of authoritarian rule. Comparative political studies 41, no. 4-5, pp.715-741.

[42]. Hicken, Allen. (2009) Building party systems in developing democracies. Cambridge University Press.

[43]. Tan, Eugene KB. (2012) SINGAPORE: Transitioning to a "New Normal" in a Post-Lee Kuan Yew Era. Southeast asian affairs 2012, no. 1, pp. 265-282.

[44]. Ortmann, Stephan. (2011) Singapore: Authoritarian but newly competitive. Journal of Democracy 22, no. 4, pp. 153-164.

[45]. Tan, Netina. (2013) Manipulating electoral laws in Singapore. Electoral studies 32, no. 4, pp.632-643.

[46]. Rodan, Garry. (2008) Singapore “exceptionalism”? Authoritarian rule and state transformation. In Political Transitions in Dominant Party Systems, Routledge, pp. 247-267.

[47]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) Red Dot United hopes to work with other parties to build a shadow government and shared platform, May 24. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/news/singapore/story20250524-6463937

[48]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) GE2025 visualization: Interactive statistics, party manifestos, election analysis, and live results, May. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/specials/singapore-general-election-2025/visualization

[49]. Jingfeng Sun. (2006) The People’s Action Party and Opposition Parties in Singapore. Academics. no. 2, pp.289 - 293.

[50]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) [GE2025] Party Manifesto Comparison – Partisan policy platforms juxtaposed on the GE2025 live dashboard. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/specials/singapore-general-election-2025/party-manifesto

[51]. James, Kieran, Bligh Grant, and Jenny Leung. (2013) Oppositional Grassroots Activism in PAP Singapore. Available at SSRN 2290028.

[52]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) [GE2025] Ou Jincai: Insights from the 2025 Singapore General Election, May 6. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/forum/views/story20250506-6295555

[53]. Ortmann, Stephan. (2009) Singapore: The politics of inventing national identity. Journal of current Southeast Asian affairs 28, no. 4, pp. 23-46.

[54]. Phipps, Marcus, Jan Brace‐Govan, and Colin Jevons. (2010) The duality of political brand equity. European Journal of Marketing 44, no. 3/4, pp. 496-514.

[55]. 8world. (2025) Leong Mun Wai: I considered my parliamentary question reasonable despite being accused of racist remarks by Shanmugam, February 7. https: //www.8world.com/singapore/leong-mun-wai-response-on-being-called-out-by-shanmugam-for-racist-remarks-2699181

[56]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) [GE2025] Cheng Soon Guan apologises over Yuen Kee Jun’s gaffe to all Singaporeans—especially the Indian community, April 27. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/realtime/singapore/story20250427-6253573

[57]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) [GE2025] Singaporeans’ identity comes first – Masagos urges not to use race and religion as political tools, April 26. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/realtime/singapore/story20250426-6248934

[58]. Lianhe Zaobao. (2025) [GE2025] Workers’ Party: Firmly uphold the principle of separation of religion and politics in our country, April 27. https: //www.zaobao.com.sg/news/singapore/story20250427-6250096