1. Introduction

Adolescence is a crucial developmental stage marked by identity exploration, emotional growth and increasing concern for interpersonal relationships. As social media platforms have become part of an individual’s daily life, teenagers’ attentions are captured by the online personas of celebrities and idols. Studies indicate that, compared with other age groups, adolescents are more susceptible to idolization and more likely to spend significant time participating in fan activities [1,2]. Under this process, many of them develop parasocial relationships, in which they become one-sidedly, emotionally attached to the celebrities [3]. Recent study found that about 61% of teenagers considered a particular celebrity to be an “intimate partner” or “soulmate” [4].

Celebrity worship, or idolatry, is a complex psychological and social phenomenon that involves emotional projection, identity reinforcement, and sometimes escape from reality [5]. Hartmann [6] pointed out that such parasocial bonds with celebrities may may serve as an imaginary intimate relationship and substitute for real-life intimacy, especially when experiencing relational instability or emotional neglect. In these cases, idols become symbols of unconditional acceptance. Adolescents can then build this “stable but impractical” relationship with an idol to reduce loneliness and emotional distress [4].

More importantly, adolescents are in the process of forming expectations about romantic and intimate relationships. These are strongly influenced by early familial upbringings, emotional experiences, and social environments. Research indicates that teenagers are particularly prone to idealizing romantic relationships, often seeing them as flawless and intensely gratifying [7]. When they lack high-quality interactions with peers, they may project their unrealistic expectations onto media-driven figures, such as a celebrity or an idol. In this way, celebrity worship may reinforce their distorted perceptions of romantic relationships. These distorted views often manifest as an excessive emphasis on finding a “perfect” partner, and an insatiable need for constant emotional validation and safety. Such expectations are usually incompatible with the complexities of genuine intimacy, which inevitably involves conflicts and compromises. If teenagers remain in these idealized parasocial relationship framework, they may find it increasingly difficult to form healthy, reciprocal relationship in real life.

The current study seeks to explore how various degrees of celebrity worship influence adolescents’ expectations of intimate relationships. Although previous research has addressed the psychological mechanisms of such parasocial relationships, most studies focus on adult populations or the general influence of media. The literature regarding how these dynamics affect teenagers remains scarce. Specifically, it is hypothesized that higher levels of celebrity worship are associated with more idealized and potentially unrealistic romantic expectations. Furthermore, it is expected that the emotional projection component of idolatry will be positively correlated with expectations of perfect emotional security and unconditional acceptance in a romantic partner. By examining this relationship, the present study aims to provide insights into how media-driven attachments might shape, or even distort, adolescents’ real-life romantic expectations.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 202 individuals initially participated in the study through an online survey distributed via the platform “Wenjuanxing”. The questionnaire included 34 items, described in detail below. To ensure the quality and relevance of responses, several exclusion criteria were applied: participants were removed 1) if they were younger than 14 or older than 35, 2) if they completed the survey in less than 70 seconds, 3) if they lacked experience engaging with or following idols, or 4) if their answers were identical across all items. After applying these criteria, the final sample consisted of 84 participants between the ages of 14 and 35 (M = 19.4, SD = 5.4), of whom 57 (67.9%) identified as female.

2.2. Study design

Participants completed a structured 34-item questionnaire, which was divided into three sections: demographics, expectations about romantic relationships, and patterns of celebrity worship. The survey was administered in Mandarin. The demographic section included three questions capturing age, gender, and prior experience with idol-following or celebrity worship.

To assess participants’ romantic expectations, a modified version of the Romantic Relationship Expectations Scale was employed (see Appendix A, https://www.wjx.cn/vm/rFrefwK.aspx#). From the original instrument, ten items were selected, with one excluded due to redundancy and lack of contextual relevance. Respondents rated their agreement with each statement using a five-point Likert scale: 1 = totally disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = totally agree. An average score across all items was calculated for each participant, with higher scores indicating more idealized or elevated expectations in romantic relationships. Scores ranged from 1.2 to 5 (M = 4.3, SD = 0.7), indicating generally high expectations within the sample.

To measure the extent and nature of celebrity worship, items were adapted from two established instruments: the College Student Celebrity Worship Scale (CSCWS; https://www.wjx.cn/xz/247454333.aspx) and the Celebrity Attitude Scale (CAS; [8]. From the CSCWS, five items were selected, with three assessing the frequency of idol-related behaviors and two evaluating the extent of knowledge participants had about their idols. The CAS contributed 16 items, organized into four subdimensions: emotional projection (four items), relationship fantasy (four items), idol identification (four items), and daily engagement with idol-related entertainment and social information (four items). This resulted in a total of 21 items assessing various aspects of celebrity worship (see Appendix B). As with the previous section, participants rated each statement on the same five-point Likert scale. Overall scores for celebrity worship were computed by averaging responses across all 21 items. Additionally, mean scores for each of the six subdimensions were calculated to explore specific behavioral and emotional patterns. The total celebrity worship scores ranged from 1.43 to 4.86 (M = 3.2, SD = 0.6). Subscale scores were as follows: behavioral frequency (range: 1 to 5, M = 3.3, SD = 1.0), idol knowledge (range: 1 to 5, M = 3.2, SD = 0.9), emotional projection (range: 1 to 5, M = 3.3, SD = 1.0), relationship fantasy (range: 1– to, M = 2.9, SD = 0.9), idol identification (range: 1.25 to 4.75, M = 3.5, SD = 0.6), and entertainment/social engagement (range: 1.5– to, M = 3.2, SD = 0.5).

2.3. Statistical analysis

All data analyses were carried out using R (base package). To test the main hypothesis, a Pearson correlation was used to examine the relationship between romantic relationship expectations and overall celebrity worship. A multiple regression analysis was then performed to see how each specific dimension of celebrity worship (such as emotional projection or relationship fantasy) contributed to predicting romantic expectations. To further explore the data, a correlation matrix was created to look at how the different celebrity worship dimensions were related to one another, and with romantic expectation.

In addition to the main analyses, exploratory tests were conducted to examine the potential effects of age and gender. Pearson correlations were used to assess the relationship between age and both romantic relationship expectations and the dimensions of celebrity worship. Independent two-sample t-tests were performed to compare male and female participants on these same variables.

3. Results

3.1. Relationship between romantic relationship expectation and celebrity worship

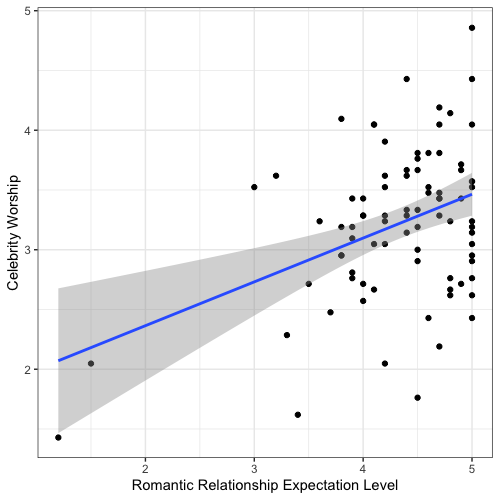

A Pearson correlation analysis showed a significant positive association between romantic relationship expectations and overall celebrity worship (r(82) = 0.39, p < .001) (see Figure 1 for the regression line). However, when a multiple linear regression was conducted to examine the predictive power of each individual subdimension of celebrity worship, no significant effects were found (p > .10). This lack of significance may be due to multicollinearity among the subdimensions. To further explore this possibility, a correlation matrix was generated to examine the relationships between the individual dimensions of celebrity worship and their respective correlations with romantic relationship expectations.

3.2. Influence between subdimensions of celebrity worship and on romantic expectation

To further explore the potential issue of multicollinearity observed in the multiple regression analysis, additional Pearson correlation tests were conducted. These analyses also aimed to examine how each subdimension of celebrity worship individually related to romantic relationship expectations. A summary of the results is presented in Table 1 below.

|

Romantic Relationship |

Behavior Frequency |

Level of Knowledge |

Emotional Projection |

Relationship Fantasy |

Idol Identification |

Entertainment Engagement |

|

|

Romantic Relationship |

|||||||

|

Behavior Frequency |

0.33** |

||||||

|

Level of Knowledge |

0.32** |

0.73*** |

|||||

|

Emotional Projection |

0.34** |

0.77*** |

0.75*** |

||||

|

Relationship Fantasy |

0.25** |

0.64*** |

0.67*** |

0.77*** |

|||

|

Idol Identification |

0.35*** |

0.55*** |

0.48*** |

0.55*** |

0.56*** |

||

|

Entertainment Engagement |

0.21 |

0.09 |

0.05 |

0.08 |

0.04 |

0.16 |

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

The correlation analysis revealed strong interrelationships among five of the six celebrity worship subdimensions, suggesting potential multicollinearity. The only exception was the social/entertainment engagement subdimension, which did not show significant correlations with the others (p > .05). Specifically, behavioral frequency was highly correlated with idol knowledge (r(82) = 0.73, p < .001), emotional projection (r(82) = 0.77, p < .001), relationship fantasy (r(82) = 0.64, p < .001), and idol identification (r(82) = 0.55, p < .001).

Similarly, idol knowledge demonstrated strong positive associations with emotional projection (r(82) = 0.75, p < .001), relationship fantasy (r(82) = 0.67, p < .001), and idol identification (r(82) = 0.48, p < .001). Emotional projection was also significantly linked with relationship fantasy (r(82) = 0.77, p < .001) and idol identification (r(82) = 0.55, p < .001), while relationship fantasy was moderately correlated with idol identification (r(82) = 0.56, p < .001). These high intercorrelations suggest that many of these dimensions may overlap conceptually or behaviorally in how individuals engage with celebrity figures.

In relation to the primary research question, further analysis showed that romantic relationship expectations were significantly and positively associated with several celebrity worship dimensions. Notably, significant correlations emerged with behavioral frequency (r(82) = 0.33, p = .002), idol knowledge (r(82) = 0.32, p = .003), emotional projection (r(82) = 0.34, p = .001), relationship fantasy (r(82) = 0.25, p = .025), and idol identification (r(82) = 0.35, p = .001). These findings suggest that adolescents who are more emotionally and behaviorally engaged in celebrity worship tend to hold more idealized views of romantic relationships.

3.3. Influence of age and gender on celebrity worship and romantic expectations

No significant relationship was found between age and either celebrity worship or romantic relationship expectations, as all correlations were nonsignificant (p > .20). This suggests that within the sampled age range (14–35), individual differences in age did not meaningfully influence levels of idol engagement or romantic ideals.

However, a gender-based comparison revealed notable differences. An independent two-sample t-test showed that male participants reported significantly lower levels of engagement in idol-related behaviors (i.e., behavior frequency) compared to female participants (t(82) = –2.46, p = .016). This result aligns with prior findings suggesting that females may be more emotionally and behaviorally involved in celebrity worship, potentially reflecting gendered patterns in emotional expression or media consumption during adolescence and young adulthood [9].

4. Disucssion

The current study attempted to investigate the association between celebrity worship and romantic expectations. Consistent with our hypothesis, there was a moderate level of positive association between general celebrity worship and idealized romantic expectations. This suggests that individuals who are more invested in celebrity or idol worship tend to have more idealistic conceptions of romantic relationships, possibly owing to the emotionally safe, one-sided nature of parasocial relationships. Teenagers who devote themselves to celebrity chasing and fantasize an intimate relationship with celebrities always have more ideal expectations that place greater emphasis on emotional safety and unconditional acceptance. This result is consistent with the theory that regards parasocial relationships as “practice” relationships or emotional templates: when celebrities act as a safe and unforced emotional resource, the ideal standard will be used as a reference for realistic interpersonal relationships [3].

Bivariate analyses also indicated that romantic expectations were significantly associated with several subdimensions of celebrity worship, including behavioral frequency, level of idol knowledge, emotional projection, relationship fantasy, and idol identification. Notably, social/entertainment engagement dimension did not significantly correlate with others, indicating a difference between passive celebrity interest (e.g., for entertainment) and high emotional arousal. This suggests that it is the intense and immersive forms of celebrity worship, such as projection, fantasy, and identification, that will mostly likely influence relationship expectations, rather than casual or entertainment-driven fan behaviors.

Although many subdimensions were significantly correlated with romantic expectations individually, multiple regression did not identify that any single subdimension was a unique predictor. This is likely due to multicollinearity, as the subscales were strongly associated with one another. In other words, adolescents who are highly engaged in celebrity worship tend to engage in many overlapping ways. Because of this high overlap, it becomes difficult to identify the specific dimensions that are responsible for the effect.

The study also found that female participants reported more idol-related behaviors compared to males, a pattern consistent with previous research on gendered fan culture and emotional expressiveness [10]. However, these differences were limited to frequency of engagement and did not extend to romantic expectations. This suggests that females would be more actively engaged in celebrity-related pursuits, but both genders internalize romantic idealizations to the same extent when emotionally engaged.

These findings have several implications for youth workers, counselors, and teachers. Since adolescents' emotional development is impacted strongly by media and parasocial relationships, it is essential that students engage critically in thinking about the nature of their celebrity attachment and form realistic standards for real-life close relationships.

5. Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations. The sample was relatively small and drawn from a convenience population, which limited generalizability. In addition, the cross-sectional design prevents any conclusions about causality. Larger and more heterogeneous samples, or longitudinal designs in subsequent research could help explore further how parasocial relationships develop over time and how they may interact with other developmental factors, such as attachment style or peer dynamics.

6. Conclusion

In summary, the study reveals that there is a noticeable correlation between intense celebrity worship and more idealized romantic expectations in adolescence. However, this association is shaped by multiple overlapping behaviors and emotional processes. While casual celebrity interest appears noninfluential, emotionally immersive and fantasy-driven idol worship may affect how adolescents conceptualize intimacy and partnership. By addressing this in practice and research, educators and mental health workers can contribute actively towards redirecting teenagers to more realistic and healthier expectations within their interpersonal relationships.

References

[1]. Giles, D. C. (2002). Parasocial interaction: A review of the literature and a model for future research. Media Psychology, 4(3), 279–305. https: //doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0403_04

[2]. Maltby, J., Giles, D. C., Barber, L., & McCutcheon, L. E. (2005). Intense-personal celebrity worship and body image: Evidence of a link among female adolescents. British Journal of Health Psychology, 10(1), 17–32. https: //doi.org/10.1348/135910704X15257

[3]. Horton, D., & Wohl, R. R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction; observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215–229. https: //doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

[4]. Gleason, T. R., Theran, S. A., & Newberg, E. M. (2017). Parasocial Interactions and Relationships in Early Adolescence. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 255. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00255

[5]. McCutcheon, L. E., Maltby, J., Houran, J., & Ashe, D. D. (2004). Celebrity worshippers: Inside the minds of stargazers. Baltimore: PublishAmerica.

[6]. Hartmann, T. (2017). Parasocial interaction, parasocial relationships, and well-being. In L. Reinecke & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of media use and well-being: International perspectives on theory and research on positive media effects (pp. 131–144). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

[7]. Connolly, J. A., & McIsaac, C. (2009). Romantic relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Contextual influences on adolescent development (3rd ed., pp. 104–151). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. https: //doi.org/10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy002005

[8]. McCutcheon, L. E., Lange, R., & Houran, J. (2002). Conceptualization and measurement of celebrity worship. British journal of psychology (London, England : 1953), 93(Pt 1), 67–87. https: //doi.org/10.1348/000712602162454

[9]. Aruguete, M. S., & Grieve, R. (2021). Individual differences in the association between celebrity worship and subjective well-being: The moderating role of gender and age. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 651067. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.651067

[10]. Harris, J. (2004). Gender, fandom, and media consumption. In A. Gray, J. Sandvoss, & C. L. Harrington (Eds.), Fandom: Identities and communities in a media culture (pp. 141–154). New York University Press.

Cite this article

Jia,X. (2025). The Relationship Between Celebrity Worship and Intimate Relationship Expectations in Adolescents. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,123,19-30.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICILLP 2025 Symposium: Psychological Perspectives on Teacher-Student Relationships in Educational Contexts

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Giles, D. C. (2002). Parasocial interaction: A review of the literature and a model for future research. Media Psychology, 4(3), 279–305. https: //doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0403_04

[2]. Maltby, J., Giles, D. C., Barber, L., & McCutcheon, L. E. (2005). Intense-personal celebrity worship and body image: Evidence of a link among female adolescents. British Journal of Health Psychology, 10(1), 17–32. https: //doi.org/10.1348/135910704X15257

[3]. Horton, D., & Wohl, R. R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction; observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215–229. https: //doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

[4]. Gleason, T. R., Theran, S. A., & Newberg, E. M. (2017). Parasocial Interactions and Relationships in Early Adolescence. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 255. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00255

[5]. McCutcheon, L. E., Maltby, J., Houran, J., & Ashe, D. D. (2004). Celebrity worshippers: Inside the minds of stargazers. Baltimore: PublishAmerica.

[6]. Hartmann, T. (2017). Parasocial interaction, parasocial relationships, and well-being. In L. Reinecke & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of media use and well-being: International perspectives on theory and research on positive media effects (pp. 131–144). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

[7]. Connolly, J. A., & McIsaac, C. (2009). Romantic relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Contextual influences on adolescent development (3rd ed., pp. 104–151). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. https: //doi.org/10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy002005

[8]. McCutcheon, L. E., Lange, R., & Houran, J. (2002). Conceptualization and measurement of celebrity worship. British journal of psychology (London, England : 1953), 93(Pt 1), 67–87. https: //doi.org/10.1348/000712602162454

[9]. Aruguete, M. S., & Grieve, R. (2021). Individual differences in the association between celebrity worship and subjective well-being: The moderating role of gender and age. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 651067. https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.651067

[10]. Harris, J. (2004). Gender, fandom, and media consumption. In A. Gray, J. Sandvoss, & C. L. Harrington (Eds.), Fandom: Identities and communities in a media culture (pp. 141–154). New York University Press.