1. Introduction

With the progress of globalisation, the focus of language teaching is gradually shifting from simple technical training to the development of intercultural communication skills. The intercultural communication (ICC) competency model proposed by Bayram considers that language learning must take into account several dimensions such as attitude, cultural knowledge, interpretation skills and interactive skills [1]. Research conducted by Feng and colleagues has also shown that learners' language proficiency has a significant influence on several aspects of intercultural communication skills, such as attitude and skills [2]. Hoff traced the evolution of the concept of intercultural communication competence, emphasising in particular its importance in 21st-century education [3]. Research by Kim et al. confirmed that primary school students can also develop intercultural communication skills through organised remote collaboration activities [4].

Currently, most international research focuses on language education for adults or adolescents, while exploration into the design and implementation of cultural input in second language teaching for primary school children remains relatively weak. On the one hand, children’s cultural comprehension is at an early stage of development, and their cognitive level has not yet been fully taken into account in teaching; on the other hand, teaching activities mostly remain at the surface level of cultural display, lacking systematic guidance and communicative application.

Drawing on Byram’s Cross-Cultural Communication Competence Model and integrating the characteristics of children’s linguistic and cultural cognition, this study puts forward cross-cultural strategies tailored to primary school second language instruction, which can serve as a reference for classroom practice. Specifically, this research helps address the gap in studies focusing on child-oriented cross-cultural teaching, while facilitating the development of students’ open cultural attitudes and rudimentary cross-cultural communication competencies.

2. Characteristics of children’s second language acquisition

Children are in a critical period of language development, and their language acquisition has a high degree of plasticity and sensitivity. Research shows that before the age of 7 is the “sensitive period” for children to acquire a second language, and the more natural and frequent the language input is at this stage, the better the effect of phonological imitation and the formation of the sense of language is [5]. At the same time, children’s thinking is mainly based on concrete images, and their abstract ability is weak, so second language teaching should rely more on contextualized and intuitive teaching methods. Although children’s cultural cognitive ability is still in the primary stage, they have a high degree of willingness to imitate and accept cultural phenomena [6]. With appropriate guidance, children can naturally absorb the cultural connotations behind the language through stories and games, and thus gradually develop a preliminary cross-cultural awareness in language learning.

3. Factors influencing cross-cultural language learning in children

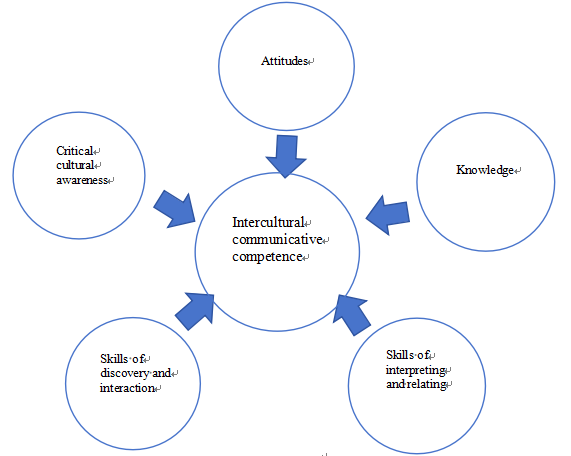

The cultivation of cross-cultural communication competencies cannot be accomplished solely through classroom instruction, given that it is shaped by a multitude of contextual and individual factors. According to Bayram's cross-cultural communication skills model, children must undergo training in several areas to truly master this skill, such as attitude, knowledge, interpretation skills, and interaction skills [1]. The cultivation of these areas is closely related to children's age characteristics, external language and cultural environments, and the educational resources they have access to. Therefore, understanding the key factors influencing children's cross-cultural language learning can help teachers design more targeted strategies in actual teaching. Figure 1 presents the five core dimensions of cross-cultural communication competence proposed by Bayram in 1997: Attitude, Knowledge, Skills of interpreting and relating, Skills of discovery and interaction, and Critical cultural awareness.

3.1. The relationship between age and the development of cultural understanding

Children’s second language acquisition is closely related to their cognitive development level. According to Piaget’s theory of cognitive development stages, elementary school children mainly engage in concrete thinking, and their ability to understand cultural symbol systems is still in its initial stage [7]. This stage is also a critical period for the development of intercultural awareness. Learners at this stage are particularly sensitive to linguistic and cultural inputs. Not only are they eager to imitate, but they also aspire to social recognition. In Bayram's model of intercultural communication competence (ICC), “attitude” is considered the main dimension of communication competence. He underscores that learners must recognize and respect cultural disparities, maintain an open-minded stance, and foster their sense of curiosity [1]. The development of this competence should align with learners’ cognitive load, utilizing appropriate cultural content and teaching methods to gradually guide the formation of cultural awareness, thereby laying the foundation for the development of other dimensions (knowledge, interpretive competence, etc.).

3.2. Differences in cultural input provided by families, society, and teachers

The development of children's cross-cultural communication skills is not only influenced by formal education in schools but also by the broader cultural environment, including families, teachers, and the media. Research has found that families' cultural orientations and parents' degree of integration into local culture have a significant impact on children's bilingual learning and cross-cultural development. For example, children from families with high levels of cultural engagement often demonstrate stronger language adaptation abilities and greater tolerance for cultural diversity [8].In the classroom, the way teachers interact with students and the teaching methods they employ are also critical. Research indicates that when teachers adopt participatory teaching methods and adapt their approaches to accommodate diverse cultural backgrounds, students develop stronger abilities to understand and accept multiple perspectives [9].

Additionally, digital media is increasingly prevalent in children's lives, and social media platforms have become important channels for transmitting cultural symbols. Imanova found that exposing young learners to cross-cultural content through social media in a targeted manner can enhance their cross-cultural awareness and sensitivity to interaction [10].

These research findings suggest that to cultivate children's comprehensive cross-cultural communication skills, cultural inputs provided at the family, school, and societal levels must complement one another.

3.3. Presentation of cultural elements in textbooks

When teaching children a second language, textbooks serve as the primary vehicle for cultural input. In fostering cross-cultural communication skills, textbooks play a crucial role in promoting “knowledge”, “interpretation”, and “critical cultural awareness” . However, recent research has highlighted the limitations of traditional English textbooks in terms of cultural representation. Keles and Yazan found that many international English textbooks still tend to emphasise Western cultural norms and products, with insufficient attention to cross-cultural differences and critical perspectives [11]. Similarly, Dahmardeh and Mahdikhani noted that while local and international textbooks have different priorities (the former focusing on local culture, the latter on cultural products), they often overlook complex cultural interactions and deeper contextual cues [12].

If cultural representation is not sufficiently diverse or in-depth, it can hinder learners' ability to understand and critically engage with cultural content. To remedy this shortcoming, the design of learning materials should take into account cultural comparison and analysis, encourage students to reflect on concrete situations, and increase the number of research-based tasks. This will enable learners to improve their interpretive skills and intercultural sensitivity.

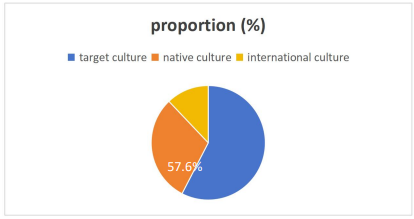

Deswila et al.’s study of Indonesian secondary school English textbooks indicates that 57.6% of the content relates to target culture, while local culture and international culture account for only 30.3% and 12.1%, respectively in figure 2. This finding indicates that the target culture occupies a significantly higher proportion in English textbooks compared to both the local culture and international culture.

4. Cross-cultural oriented teaching strategies

To develop intercultural communication skills, educational activities must take into account both language and culture. When children learn a second language, their cognitive abilities and understanding of culture are not yet mature, so educational strategies must strike a balance between acceptability and development. According to Byram's ICC model, educational design must be structured around five fundamental dimensions, with particular emphasis on “attitude”, “knowledge” and “interpretation and interaction skills”. The instructional approaches adopted by educators and the selection of teaching materials exert a particularly pivotal role in this context.

4.1. Story-based teaching method

Language learning during childhood relies heavily on concrete and vivid language input, and stories are one of the most natural and effective cultural carriers. By presenting representative English cultural tales, such as Jack and the Beanstalk and the legend of Halloween, students can not only understand the content of the text, but also come into contact with implicit elements of the target culture, such as beliefs, values and social roles [1]. This teaching method can help cultivate the “knowledge” aspect of the ICC model. In addition, through the experiences, actions, and emotional responses of the characters in the story, students can truly identify with and understand the target culture, which is also beneficial for internalizing the “attitude” aspect.

When designing story-based lessons, teachers should pay particular attention to the cultural elements hidden within stories, such as values, social norms, or power structures, and not limit themselves solely to vocabulary and syntactic structures. For example, by discussing the holidays, family names, or polite expressions mentioned in the stories, teachers can encourage students to discover cultural differences for themselves. In addition, teachers can encourage students to repeat, continue or adapt the stories so that they memorise cultural information as part of their language exercises and thus achieve a “comprehensible input” of cultural information [14].

4.2. Scenario simulation and role-playing

Designing teaching activities that simulate real-life situations allows students to learn through practice, and role-playing is an excellent method for this purpose. It not only helps students practise their communication skills but also aids in their understanding of different cultures. In cross-cultural teaching, role-playing not only improves students' language skills but also makes them aware of the differences in behavioural norms across cultural contexts. For example, when students simulate scenarios such as 'visiting a foreign friend,’ 'asking for directions at the airport,’ or 'communicating at an international cultural festival,’ they must respond based on their understanding of cultural norms to convey their message effectively [6].

These methods can help cultivate the interactive ability and explanatory association ability in the ICC model. Research shows that allowing students to personally experience roles in other cultures can help them gain a deeper understanding of the underlying meaning systems and communication logic of those cultures [15]. Additionally, after simulated activities, teachers can organize group discussions and reflections to guide students in considering the rationality and differences of various cultural behaviors within the context, thereby establishing a “experience-reflection-expression” teaching cycle.

4.3. Cross-cultural comparison activities

In intercultural education, cultural comparison is a commonly used and effective method. By organically comparing the local culture and the target culture, students are helped to become aware of cultural relativity and to avoid misunderstandings or stereotypes associated with a monocultural perspective. Teachers can encourage students to analyse the similarities and differences between different cultures by focusing on topics such as holidays like Chinese New Year and Christmas, rules of etiquette such as handshakes and greetings, and themes such as titles and family structures. Then, students can try to identify the cultural roots underlying these differences.

Liddicoat and Scarino argue that comparative cultural education should not merely focus on showcasing superficial cultural symbols; the key is to help students understand the underlying social structures and values behind these cultures [16]. This approach can help cultivate students' interpretive skills and critical cultural awareness. Take the topic of 'Why are Western children more independent?’ as an example. Teachers can guide students to think about it from the perspectives of social systems, educational philosophies, and family structures, rather than settling for superficial understanding, thereby cultivating the ability to deeply interpret culture.

4.4. Teachers' guiding role and cultural reflection activities

In cross-cultural education, teachers should not only teach knowledge, but also enhance students' cultural awareness and guide them to develop critical thinking skills.Through conscious questioning, the construction of comparative frameworks, and the organization of discussions, teachers can help students gradually develop an awareness of cultural differences and learn to make rational judgments. This teaching strategy is very helpful for cultivating “critical cultural awareness” in the ICC model.

Cultural reflection activities can be carried out in the following ways: (1) Organize debates or discussions in class, for example on the topic “Is direct expression more effective?”; (2) Assign writing assignments, such as “Foreigners in my eyes”; (3) Ask groups to conduct research and present their findings, such as “Observing cultural diversity in the community”; (4) Conduct comparative analyses, for example, identifying cultural conflicts in English conversations and their causes. These activities help students bridge the gap between linguistic input and output, and gradually move from “knowing how to use the language” to “understanding the culture.”

Schat et al. believe that the key to cross-cultural competence lies not in “how much cultural knowledge a person has”, but in whether learners “can respond appropriately to cultural differences” [17]. The role of teachers is to guide students from being passive recipients of cultural knowledge to becoming critical constructors of cultural meaning.

5. Conclusion

This study explores the theoretical basis and practical approaches for intercultural teaching in children’s second language acquisition, starting from the concept of Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC). By analyzing the characteristics of children’s language and cultural cognitive development and integrating the five dimensions of Byram’s ICC model, the article proposes four intercultural teaching strategies suitable for the primary school stage: story-based teaching, scenario simulation and role-playing, cross-cultural comparison activities, and teacher-guided cultural reflection activities.

Research has found that children have strong imitation skills and are highly sensitive to culture, but their understanding of culture is still at an early stage. Therefore, incorporating specific and culturally relevant content into teaching—such as festival legends, everyday scenes, and examples of cultural differences—can stimulate students' interest and help them better understand and respect other cultures. In addition, teachers should design tasks centred around questions to guide students through comparison, interpretation, and expression, gradually cultivating their “interpretive connection skills” and “critical cultural awareness”.

Based on the findings of this study, we believe that primary school foreign language education should no longer focus solely on “language teaching” but should shift to a teaching model that emphasizes both “language and culture”. Specifically, first, teachers must undergo systematic cross-cultural teaching training so that they can better help students understand cultural differences that arise in the classroom; second, textbooks should include authentic cultural contexts and cross-cultural comparisons to avoid reinforcing cultural stereotypes; Third, assessments of students should incorporate aspects such as cultural understanding, cultural attitudes, and reflective abilities; fourth, we should encourage the use of situational simulations and teaching methods to create a cultural environment that immerses students.

Regarding future research, we can explore practical classroom studies, track students’ cultural performance, and integrate multimedia resources to promote deeper integration between children's cross-cultural education and language teaching.

References

[1]. Byram M.(1997) Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

[2]. Feng, Meina; Aziz, Muhammad Noor Bin Abdul; Syarizan, Dalib. (2024) Exploring the relationship between language competence and Intercultural Communicative Competence among English as a Foreign Language learners: A Mixed‑Methods Study. International Journal of Educational Methodology., 10: 671–684.

[3]. Hoff, Hild Elisabeth. (2020) The Evolution of Intercultural Communicative Competence: Conceptualisations, Critiques and Consequences for 21st Century Classroom Practice. Intercultural Communication Education., 3: 55–74.

[4]. Kim, Soojin. (2020) Engagement beyond a Tour Guide Approach: Korean and US Elementary School Students’ Intercultural Telecollaboration. Intercultural Communication Education., 3: 99-117.

[5]. Lenneberg EH. (1967) Biological Foundations of Language. New York: Wiley.

[6]. Krashen SD. (1982) Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon.

[7]. Piaget J.(1969) The Psychology of the Child. New York: Basic Books.

[8]. Uchikoshi Y, Lindblad M, Plascencia C, Tran H, Yu H, Bautista KJ, Zhou Q. (2021) Parental acculturation and children’s bilingual abilities: A study with Chinese American and Mexican American preschool DLLs. Front Psychol., 12: Article761043.

[9]. Cardenal, M.E., Díaz-Santana, O. and González-Betancor, S.M. (2023), "Teacherstudent relationship and teaching styles in primary education: A model of analysis", Journal of Professional Capital and Community., 8 : 165- 183.

[10]. Imanova, S. (2022) The role of social media in the development of intercultural competence among university students in Azerbaijan. International Journal of Social and Educational Innovation, 9: 7–16.

[11]. Keles, U., Yazan, B. (2023) Representation of cultures and communities in a global ELT textbook: A diachronic content analysis.. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 36: 1325–1346.

[12]. Dahmardeh, M., Mahdikhani, A. (2025) Cultural representation in English language textbooks: A comparative study of local and international editions. International Journal of Language Studies., 19: 53–76.

[13]. Deswila S, Sofendi, Vianty M. (2021) Culture representations in Indonesian EFL textbooks: A content analysis. J Nusantara Stud., 6: 1–22.

[14]. Kramsch C. (1993) Context and Culture in Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press; .

[15]. Hall ET.(1976) Beyond Culture. New York: Anchor Books.

[16]. Liddicoat AJ, Scarino A. (2013) Intercultural Language Teaching and Learning. Wiley-Blackwell.

[17]. Schat, E., van der Knaap, E., de Graaff, R. (2022) Reconceptualizing Critical Cultural Awareness for the Context of FL Literature Education: the Development of an Assessment Rubric for the Secondary Level. Intercultural Communication Education., 5: 125–142.

Cite this article

Cao,S. (2025). A Study of Children’s Second Language Acquisition Teaching Strategies from the Perspective of Intercultural Communication. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,123,31-37.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICILLP 2025 Symposium: Psychological Perspectives on Teacher-Student Relationships in Educational Contexts

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Byram M.(1997) Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

[2]. Feng, Meina; Aziz, Muhammad Noor Bin Abdul; Syarizan, Dalib. (2024) Exploring the relationship between language competence and Intercultural Communicative Competence among English as a Foreign Language learners: A Mixed‑Methods Study. International Journal of Educational Methodology., 10: 671–684.

[3]. Hoff, Hild Elisabeth. (2020) The Evolution of Intercultural Communicative Competence: Conceptualisations, Critiques and Consequences for 21st Century Classroom Practice. Intercultural Communication Education., 3: 55–74.

[4]. Kim, Soojin. (2020) Engagement beyond a Tour Guide Approach: Korean and US Elementary School Students’ Intercultural Telecollaboration. Intercultural Communication Education., 3: 99-117.

[5]. Lenneberg EH. (1967) Biological Foundations of Language. New York: Wiley.

[6]. Krashen SD. (1982) Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon.

[7]. Piaget J.(1969) The Psychology of the Child. New York: Basic Books.

[8]. Uchikoshi Y, Lindblad M, Plascencia C, Tran H, Yu H, Bautista KJ, Zhou Q. (2021) Parental acculturation and children’s bilingual abilities: A study with Chinese American and Mexican American preschool DLLs. Front Psychol., 12: Article761043.

[9]. Cardenal, M.E., Díaz-Santana, O. and González-Betancor, S.M. (2023), "Teacherstudent relationship and teaching styles in primary education: A model of analysis", Journal of Professional Capital and Community., 8 : 165- 183.

[10]. Imanova, S. (2022) The role of social media in the development of intercultural competence among university students in Azerbaijan. International Journal of Social and Educational Innovation, 9: 7–16.

[11]. Keles, U., Yazan, B. (2023) Representation of cultures and communities in a global ELT textbook: A diachronic content analysis.. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 36: 1325–1346.

[12]. Dahmardeh, M., Mahdikhani, A. (2025) Cultural representation in English language textbooks: A comparative study of local and international editions. International Journal of Language Studies., 19: 53–76.

[13]. Deswila S, Sofendi, Vianty M. (2021) Culture representations in Indonesian EFL textbooks: A content analysis. J Nusantara Stud., 6: 1–22.

[14]. Kramsch C. (1993) Context and Culture in Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press; .

[15]. Hall ET.(1976) Beyond Culture. New York: Anchor Books.

[16]. Liddicoat AJ, Scarino A. (2013) Intercultural Language Teaching and Learning. Wiley-Blackwell.

[17]. Schat, E., van der Knaap, E., de Graaff, R. (2022) Reconceptualizing Critical Cultural Awareness for the Context of FL Literature Education: the Development of an Assessment Rubric for the Secondary Level. Intercultural Communication Education., 5: 125–142.