1. Introduction

Due to the rapid development of social productivity, the continuous expansion of markets, and the increasing scale of enterprises, the resulting social environmental and governance issues have been named “Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG).” Corporate ESG roughly covers three elements: environmental management, social responsibility, and corporate governance. However, there are still many challenges in effectively managing these factors. Regarding this issue, the primary consideration is how to ensure the honesty and transparency of corporate ESG information, which is also called ESG disclosure—the public announcement of a company's progress toward its environmental, social, and governance objectives.

Currently, in many academic research, ESG social disclosure is primarily categorized into voluntary disclosure mechanisms or mandatory disclosure mechanisms. In this way, mandatory disclosure is now widely practiced in today's society, requiring companies to disclose specific ESG issues in accordance with detailed regulations. However, existing research has not provided sufficient evidence to demonstrate the effectiveness of mandatory ESG disclosure, indicating a need for further studies in this area. The voluntary disclosure mechanism has consistently been a popular topic in ESG disclosure reform discussions. However, this approach may raise another problem: given that managers have significant discretion in measuring and reporting their companies' ESG performance, it could ultimately lead to a lack of credibility in the ESG information disclosed by companies. This could further reduce market and corporate credibility, impact overall social ESG management, and potentially fuel social conflicts [1].

In addition, it is worth noting that mandatory disclosure mechanisms and voluntary disclosure mechanisms can be interconnected. For instance, certain mandatory disclosure requirements may encourage companies to voluntarily disclose the ESG information they report.

2. Theoretical foundations

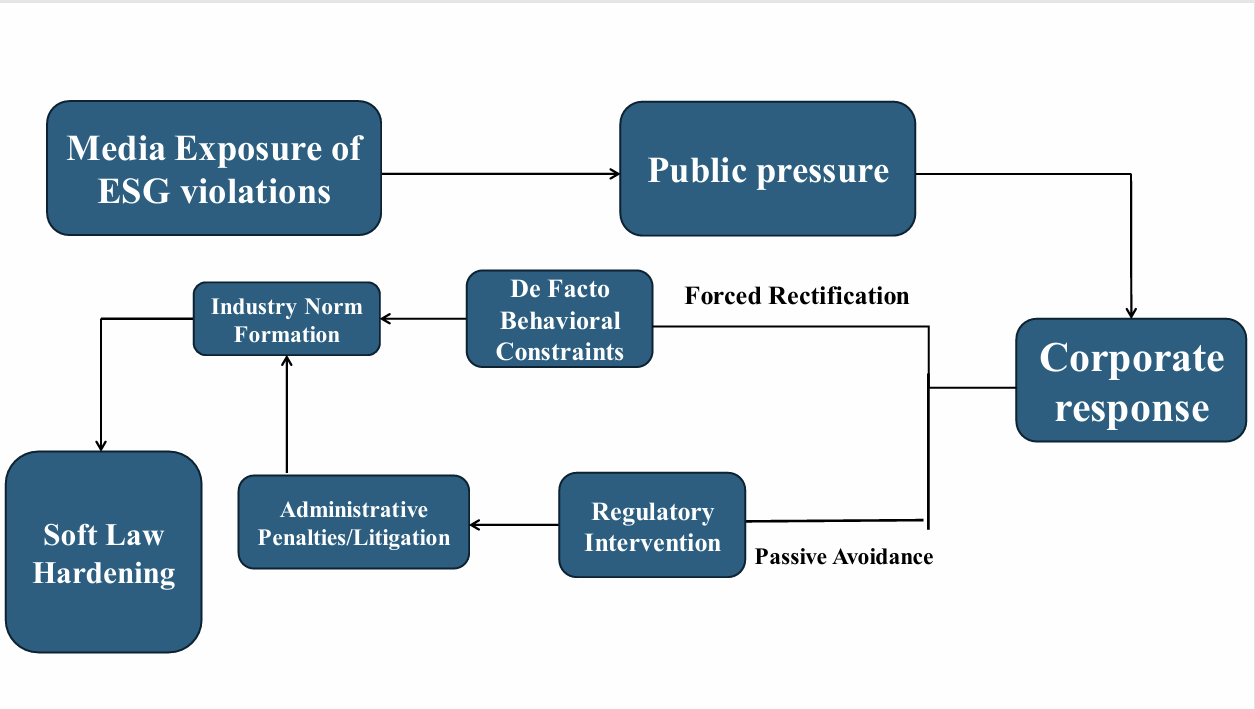

As illustrated in Figure 1, the logical chain of this study integrates the following three theories:

First, the media uses online platforms to rapidly spread the news of the company's ESG shortcomings. This generates significant public attention, creating powerful public pressure that forces the company to respond. In such cases, companies may choose to actively adjust or passively evade. However, when companies negatively evade, public opinion will pressure the supervisory authorities to supervise and impose administrative penalties, which require companies to improve their ESG disclosures. Both situations can serve as models for subsequent ESG industry practices. Over time, these new examples of change will form unwritten rules for ESG disclosure within the industry. Companies will gradually comply until, ultimately, relevant administrative departments establish new mandatory regulations, achieving the “hardening of soft law.”

2.1. Responsive regulation

Responsive regulation was summarized by scholars such as Philippe None and Philip Selznick of the Berkeley School in the United States. They advocate leveraging discretionary authority to integrate the spirit of upholding legal justice into government supervision of society. This can help to establish a more flexible yet standardized mechanism that consistently aligns with societal needs, providing a pathway for negotiated conflict resolution and expanded legal participation. On this basis, scholars such as Ian Ayres and John Braithwaite have proposed responsive supervision in conjunction with administrative models. This approach emphasizes fostering collaborative negotiation between supervisors and supervised entities through differentiated supervision, interactive feedback, and empowerment of subjects. It aims to shape subject consciousness and capabilities while enhancing the ability to supervise [2].

In this study, corporations, as supervised entities, will voluntarily disclose ESG information that meets public expectations due to media oversight and exposure pressure. This approach helps foster corporate self-awareness and compliance consciousness regarding mandatory ESG disclosure requirements. For companies that fail to voluntarily comply with mandatory regulations, media exposure will generate significant public pressure, compelling them to rectify or improve their practices. Beyond this, applying a responsive regulatory model within ESG frameworks also enables companies to continuously align their disclosures with the real evolving expectations of the market and the public, thereby fostering adequate two-way interaction between businesses and society.

But it must be emphasized that responsive supervision constitutes a multi-objective oversight system jointly established by various stakeholders. Its normal and effective operation requires all participants to possess standardized discretionary capabilities and a commitment to upholding the rule of law, while also engaging in reasonable division of labor and collective participation within this oversight framework [2]. While this remains somewhat idealistic in today's reality, it does not hinder the applicability of responsive supervision as a reference point for corporate ESG disclosure.

2.2. Agenda melding

Traditional agenda-setting theory believes that people passively receive information from traditional mass media such as newspapers and television, and their daily communication topics are also set for them top-down by traditional media. However, with the rapid development of social media and the emergence of self-media platforms, traditional agenda-setting theory has faced significant challenges, leading to the emergence of agenda fusion theory. However, with the rapid development of social media and the emergence of self-media platforms, traditional agenda-setting theory has faced significant challenges, leading to the emergence of agenda-melding theory.

Agenda-melding theory centers on audiences as its primary subjects, emphasizing the social influence on the social media from audiences [3]. Individuals actively seek out others who share their perspectives and needs through various social media platforms, and merge into a cohesive group. Such groups exhibit a strong sense of social belonging. In short, it is research about public opinion generation in contemporary society.

In this study, an event initially spreads within a small circle or platform. Individual users voluntarily utilize social media to actively distribute and discuss the topic based on their own need for identification, thereby transforming the “rumor” into a public “issue.” Throughout this process, the audience discussing this topic has steadily expanded. Taking advantage of the platforms provided by social media, the issue has gained increasing prominence, ultimately forming a powerful wave of online public opinion. This wave directly conveys the demands of the public and the market to enterprises, which can influence their ESG disclosure practices.

2.3. Stakeholders

The stakeholder theory was first proposed by management scholar R. Edward Freeman, who posited that a company's survival and development depend on the support of relevant interest groups that cover shareholders. Each stakeholder holds ownership in the enterprise while simultaneously sharing its risks. Together, they govern the company, with the enterprise ultimately balancing and fulfilling the interests of these groups [4]. The distribution of corporate value directly reflects corporate social responsibility. For a company to acquire and realize value, it must accept investments from stakeholders. Therefore, stakeholders serve as the guiding force for the establishment and operation of a company.

The implementation of corporate ESG is not about charity, but about managing risks, maintaining reputation, and thereby securing a sustainable license to operate. In such a context, social discourse amplified by contemporary media exerts powerful constraints on corporate ESG disclosure practices. This makes it imperative for companies to not only satisfy internal stakeholders—such as employees, managers, and shareholders—but also focus on external stakeholders, including consumers, government supervisory bodies, and creditors. Consequently, businesses must continually enhance the breadth and depth of their ESG disclosures.

3. The ultimate realization of “soft law hardening”

In the early days, under the theoretical influence of Austin's positivist jurisprudence, soft law was often an ignored aspect, with law largely confined to existing, explicit, and well-established statutes. However, it was only after Kelsen, modifying Austin's positivist conception of law, demonstrated that “law ought to be normative and prescriptive” that soft law gradually came into public view [5].

The current ESG disclosure mechanisms for companies, as previously mentioned, primarily consist of mandatory and voluntary disclosure. However, the regulations governing mandatory disclosure inherently possess a lag and a principle-based nature of codified law, making it difficult to flexibly address the ever-changing realities of society. While voluntary corporate disclosure can effectively address the flexibility issues inherent in mandatory disclosure mechanisms, relying on voluntary compliance with “soft law” alone would lead to a severe trust crisis and enforcement gap. By strengthening the soft law constraints on corporate ESG disclosure through media-driven public pressure, companies can be compelled to voluntarily adhere to ESG disclosure mechanisms. This approach not only facilitates the gradual evolution of soft law into hard law but also ensures that businesses do not arbitrarily violate ESG soft law regulations during this transition process.

Statute law, as a codified body of rules possessing legitimacy, stands as the most binding and precisely articulated source of law in the world. As more legal scholars recognize the importance of codified law, the common law and civil law systems are increasingly converging in today's world, and the volume of statute law continues to grow. Therefore, advancing corporate ESG hard laws through media oversight to keep pace with the times and continuously updating and refining ESG disclosure mechanisms will be crucial methods for regulating markets and enterprises.

4. Legal optimization recommendations for public opinion regulation

While public opinion can exert influence to compel corporate disclosure of ESG information, it may also disrupt normal market operations and administrative management. Today, acts of disrupting social governance through public opinion are abundant. Therefore, while utilizing media oversight of enterprises, establishing a balanced supervisory ecosystem to maintain market and social stability is also of utmost importance. Below are some suggestions on how to build such a balanced regulatory ecosystem.

First, specific duty clauses for media ESG reporting can be established. Mainstream media outlets and major information platforms should be required to fulfill reasonable fact-checking obligations before publishing ESG allegations that might trigger significant public attention. This includes notifying the government's market supervision authorities or citing authoritative sources such as court rulings or reports from international institutions.

Additionally, for certain small media outlets and self-media platforms that may disseminate false information, they should be deterred in advance. For those who have already done so, explicit penalties and mechanisms for prompt corrections and retractions should be established.

The government may also establish “undercover inspection teams” with close ties to the media, which would conduct in-depth investigations in markets and enterprises. Upon discovering violations of ESG disclosure regulations by companies, these teams would promptly expose such violations through media outlets to generate public discourse. This approach not only enhances the oversight efficiency of both government and media but also enables strict control over media conduct. Furthermore, such media outlets could be granted official authorization by the government to conduct exposures, thereby verifying the authenticity of their reports to the public [6].

5. Conclusion

This dissertation primarily explores how to utilize media-generated public pressure to regulate corporate ESG disclosure practices, thereby meeting public and governmental expectations regarding ESG. Ultimately, the new mandatory corporate ESG disclosure regulations aligned with contemporary demands will be established—effectively transforming “soft law into hard law”.

Given the rapid dissemination speed and powerful influence of modern media, the first step is to reflect stakeholder demands through media coverage, supplementing information that the government mandates on corporate ESG compliance cannot promptly address. This regulates corporate ESG disclosure practices, gradually fostering voluntary compliance with soft law. Ultimately, it provides opportunities and references for establishing new hard law. This constitutes the proposed path outlined in this essay: a media-driven mechanism for corporate ESG disclosure that transforms soft law into hard law.

However, the use of public opinion also carries the constant risk of disrupting market and social environments. While this paper proposes corresponding control strategies, it lacks practical information and relevant theoretical validation, which deserves further in-depth exploration and understanding in subsequent research.

References

[1]. Tsang, A., Frost, T., & Cao, H. (2023). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure: A literature review. The British Accounting Review, 55(1), 101149.

[2]. Chen Xi. (2024). Regulatory Challenges and Responsive Regulation in the Era of Securities Registration System. Enterprise Economy, 43(10), 97-107. doi: 10.13529/j.cnki.enterprise.economy.2024.10.009.

[3]. Ma Zhihao & Ge Jinping. (2013). The Mechanism of Online Public Opinion from Rumor to Agenda: An Analysis of Network Agenda Melding in the Context of Social Media. International Journalism, 35(07), 16-25. doi: 10.13495/j.cnki.cjjc.2013.07.002.

[4]. Wang Qi & Yang Anling. (2021). A Review of Research on Stakeholders' Influence on Corporate Social Responsibility. Commercial Accounting, (18), 19-24.

[5]. Wang Lan. (2021). The Positioning of Corporate Soft Law and Its Connection with Corporate Law. China Legal Science, (05), 266-283. doi: 10.14111/j.cnki.zgfx.2021.05.007.

[6]. Liu Bao & Liu Mingxin. (2023). Discussion on the Linkage Mechanism Between Media and Government in Environmental Protection—Based on the Practice of "Shandong Province Ecological and Environmental Issues Undercover Inspection Team". Omni-Media Exploration, (10), 51-53.

Cite this article

Xie,Z. (2025). A Theoretical Analysis of Improving ESG Disclosure Mechanisms Through Media Disclosure Models. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,115,8-12.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICILLP 2025 Symposium: Property Law and Blockchain Applications in International Law and Legal Policy

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Tsang, A., Frost, T., & Cao, H. (2023). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure: A literature review. The British Accounting Review, 55(1), 101149.

[2]. Chen Xi. (2024). Regulatory Challenges and Responsive Regulation in the Era of Securities Registration System. Enterprise Economy, 43(10), 97-107. doi: 10.13529/j.cnki.enterprise.economy.2024.10.009.

[3]. Ma Zhihao & Ge Jinping. (2013). The Mechanism of Online Public Opinion from Rumor to Agenda: An Analysis of Network Agenda Melding in the Context of Social Media. International Journalism, 35(07), 16-25. doi: 10.13495/j.cnki.cjjc.2013.07.002.

[4]. Wang Qi & Yang Anling. (2021). A Review of Research on Stakeholders' Influence on Corporate Social Responsibility. Commercial Accounting, (18), 19-24.

[5]. Wang Lan. (2021). The Positioning of Corporate Soft Law and Its Connection with Corporate Law. China Legal Science, (05), 266-283. doi: 10.14111/j.cnki.zgfx.2021.05.007.

[6]. Liu Bao & Liu Mingxin. (2023). Discussion on the Linkage Mechanism Between Media and Government in Environmental Protection—Based on the Practice of "Shandong Province Ecological and Environmental Issues Undercover Inspection Team". Omni-Media Exploration, (10), 51-53.