1. Introduction

Henan Province, with a population exceeding 99 million [1], faces a striking paradox in its education system. It has the largest K-12 student population in China, yet its higher education enrollment rate remains significantly below the national average. In a setting marked by unequal resource distribution, secondary students in Henan are caught in a pattern of high academic workload with limited effectiveness. On average, they devote 12.6 hours per day to study, primarily filled with repetitive knowledge drills. At the same time, participation in extracurricular activities falls below 17 percent. This system emphasizes memorization over comprehensive growth, leaving little opportunity for interdisciplinary inquiry or personal interests. The issue is compounded by Henan’s relatively weaker economic standing and scarce educational resources.

From a sociological viewpoint, Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital [2] offers insight into this dilemma. Students in Henan have limited access to varied cultural and educational assets, which restricts their ability to accumulate the symbolic capital essential for well-rounded development. Symbolic capital here refers to the recognition and legitimacy gained through valued cultural competencies. This shortage stands in sharp contrast to the experiences of students in more economically developed regions. The educational environment in Henan reflects a structural problem often discussed in theories of cultural reproduction. Students from less developed areas are pushed to compete intensely within an exam-focused system, where educational capital is often reduced to test scores and credentials. In the process, the cultivation of critical thinking, artistic awareness, and practical skills is neglected. These are precisely the forms of cultural capital that matter in more privileged educational settings.

By comparison, Beijing has used its resource advantages to build a relatively mature model of comprehensive education. Guided by principles of subject integration and diverse assessment methods [3], leading schools such as Beijing No. 4 High School and The High School Affiliated to Renmin University of China have reshaped educational pathways in three key ways. They redesigned curricula to include interdisciplinary projects, with about 40 percent of class time dedicated to inquiry-based learning in sciences and social studies. They also increased resource investment, with schools spending an average of 2.78 million yuan annually to establish maker spaces and art studios [4]. Moreover, they reformed evaluation systems, incorporating community service and social practice into senior high school entrance assessments. These initiatives reflect the core idea of holistic education, which aims to develop embodied capabilities rather than serve as a one-dimensional source of knowledge.

However, Henan’s direct replication of the Beijing model faces deep-seated contradictions. For one, Henan’s education expenditure per student is only one-quarter of Beijing’s, making it hard to support high-cost activities. In terms of teaching philosophy, 73% of Henan teachers prioritize “exam-oriented efficiency” and hold a utilitarian attitude toward quality education. What’s more, although policy requirements for examination standards aim to assess students’ expanded capabilities and innovative thinking, provincial unified exams still take knowledge point coverage as the core metric. This has compressed the implementation space for school-based courses. This aligns with the warnings of policy transfer theory [5]: transplanting policies without considering local field characteristics may exacerbate educational inequality.

Therefore, this study poses the core question:

How to localize Beijing’s educational model in Henan’s system to enhance middle school students’ comprehensive subject capabilities and all-round development?

This paper aims to explore the transformation pathways for establishing a “Henan-ized” educational model, with a comparative analysis focusing on three core dimensions: curriculum adaptation mechanisms, resource leverage effects, and the feasibility of evaluation reforms. A key objective of this exploration is to avoid two extremes in the model’s development: the crude transplantation of external educational models and the entrenchment of long-standing exam-oriented practices.

2. Literature review

The cross-regional localization of the “5-dimension education” educational model faces the challenge of whether it can be deeply adapted. Steiner Khamsi [6] noted in their study on the transplantation of the Nordic educational model in developing countries that policy transfer must go through three stages: deconstruction, selection, and reconstruction. However, if these three steps are not fully implemented, it is easy to end up with a mere replication of the model without optimizing it to suit local conditions. This theory is validated in the case of Henan Province and Beijing: county-level schools view out-of-province study tours as mere visits to tourist attractions, as rigid evaluation systems force teachers to prioritize meeting formal requirements over substantive learning. DiMaggio and Powell [7] further explained this phenomenon using institutional isomorphism theory: coercive isomorphism is more likely to occur in resource-scarce regions. For example, middle schools in Zhoukou City often replicate Beijing’s elective course schedules without corresponding teacher resources, failing to achieve the desired outcomes. These studies reveal the ineffectiveness of direct transplantation but fail to delve into the innovative possibilities of Henan’s rural schools’ unique circumstances [8]. I found that grassroots teachers employed “policy tailoring” to integrate elements of the Beijing model into the local framework, such as replacing Beijing opera with Henan opera in aesthetic education. However, this strategy has not yet formed a systematic paradigm.

In terms of resource allocation, the large-class teaching model widely adopted in Henan significantly constrains the advancement of “five-dimensional education.” According to Black’s resource dilution hypothesis, meta-analyses have confirmed that when class sizes exceed 55 students, average teacher-student interaction time decreases by 64% [9]. This reality leads teachers in Henan’s counties to assign substantial written homework, thereby crowding out teaching time allocated for aesthetic education and labor courses [10]. Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital further reveals the underlying structural issues: Beijing students typically accumulate tacit cultural capital through informal learning pathways, whereas rural students in Henan face greater barriers to accessing similar opportunities [2]. Notably, an educational experiment conducted at a rural school in Anhui Province offers a potentially applicable model for Henan. This experiment substituted costly urban field trips with local rice cultivation activities, effectively leveraging indigenous resources to develop alternative forms of capital. It maintained the cultivation of scientific inquiry skills while achieving a 73% cost reduction. Such practices align with Sen’s theory of feasible capabilities, demonstrating that even in resource-constrained environments, it remains possible to expand students’ cognitive development space [11]. However, existing research has yet to fully explore the practical challenges Henan faces in substantively promoting students’ holistic development under the unique pressure of the college entrance examination.

Evaluation reform is a crucial tool for breaking the dominance of academic performance. Data from the Beijing Municipal Education Commission shows that after comprehensive quality assessment accounted for 30% of the middle school entrance exam, school club participation rates jumped from 41% to 89%. This aligns with Wiggins and McTighe’s backward design logic [12]: establishing goals to drive curriculum restructuring. However, Henan’s educational reforms face numerous challenges. County education bureaus still allocate resources based on admission rates, and 72% of rural parents believe that courses such as music, physical education, and art will affect the learning of academic subjects like mathematics and Chinese.

Existing literature has three limitations: First, it overly focuses on optimizing provincial policies while neglecting whether these policies are effectively implemented at the county level and in rural schools. Second, evaluation indicators for comprehensive development overly rely on urban resources and are not adapted to the context of county towns lacking facilities such as museums. Third, the compensatory education model [13] does not address Henan parents’ extreme pursuit of graduation rates. This study aims to address these gaps by analyzing local innovations by Henan educators to explore a symbiotic path between “reducing academic burdens” and “enhancing educational quality.”

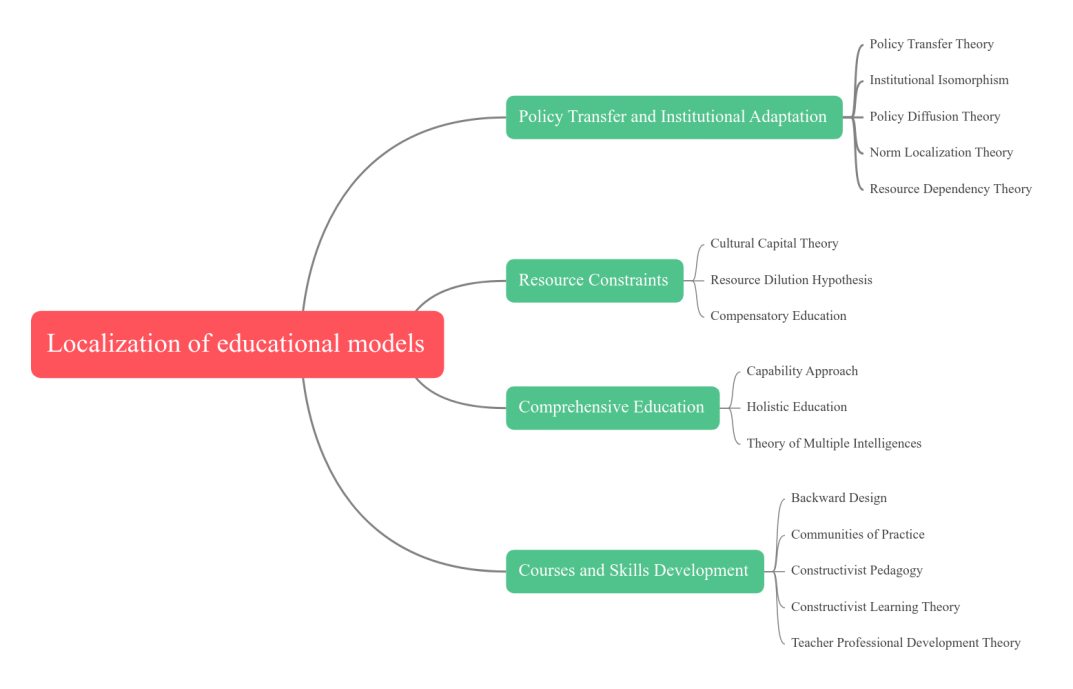

3. Theoretical framework

This study systematically elucidates the localization process of the Beijing education model in Henan by integrating four theoretical perspectives, focusing on analyzing the key factors influencing the model’s cross-regional adaptability and their interactive mechanisms.

First, the theories of policy diffusion and institutional adaptation help understand the intrinsic processes of education model transplantation and local transformation. Policy diffusion theory [14] can be applied to examine the voluntary or coercive mechanisms Henan employed when introducing the Beijing model. It places particular focus on the completeness of policy transfer, including the tendency to replicate only the curriculum framework when resources are limited. Institutional isomorphism theory [7] explains the behavioral choices of county-level schools in Henan when facing three types of isomorphism pressures: coercion, imitation, and norms. It adopts the perspective of external pressures inducing institutional convergence to elaborate on these choices. Policy diffusion theory [15] focuses on pathways for policy transmission across regions, enabling analysis of how Beijing, as a policy pilot area, influenced Henan through administrative systems or regional collaboration. Norm localization theory [16] emphasizes local actors’ active reconstruction of external concepts to achieve effective integration between external norms and local realities. This theory applies to examining the localized interpretation and meaning reshaping of the “high-quality education” concept during its transplantation from Beijing to Henan.

The second group consists of theories on educational equity and resource allocation, which analyze how to avoid exacerbating regional educational inequality during the transfer of educational models. Cultural Capital Theory [2] can be used to compare resource disparities between Beijing and Henan students. For example, Beijing students can accumulate embodied capital through museum-based field studies, while rural Henan students must develop alternative capital, such as transforming agricultural culture into labor courses. The Resource Dilution Hypothesis [9] explains how large class sizes in Henan lead to a decrease in per-student resources, forcing teachers to rely on “question banks”. Compensatory Education [13] aims to provide additional educational support for disadvantaged children. It can be used to consider allocating extra educational resources to resource-disadvantaged groups, but must avoid stigmatization.

The third group consists of theories on comprehensive development education. These theories define the diverse connotations of comprehensive development and its implementation paths in different regions. Marxist comprehensive development theory emphasizes the full and free development of human potential in multiple dimensions, including physical, intellectual, personal, and social aspects, and opposes one-sided skill or knowledge indoctrination. The Five-Education Approach Theory defines the five dimensions of “comprehensive development” as moral education, intellectual education, physical education, aesthetic education, and labor education. This theory can be used to analyze structural imbalances in Henan’s implementation. The Capability Approach [11] advocates that education should expand students’ freedom of thought and cultivate their critical thinking skills, rather than solely focusing on exam-oriented functions. Holistic Education [17] emphasizes the comprehensive development of students’ cognitive, emotional, social, and spiritual aspects, integrating humanistic psychological ideas. It can be used to examine the design of clubs and psychological courses in the Beijing model. The Theory of Multiple Intelligences [18] emphasizes the diversity of human intelligence, providing a theoretical foundation for the cultivation of “comprehensive subject-based capabilities.” It suggests that Henan can meet the needs of students with different intelligence types through “tiered course design,” avoiding a one-size-fits-all approach to quality education.

The fourth group is course design and competency development theory. These theories explain the pathways for cultivating comprehensive subject competencies and localized teaching methods. The Backward Design Theory [12] can be used to reconfigure the curriculum development process in Henan Province schools. The goal should be to cultivate students’ comprehensive subject-specific capabilities, designing assessment evidence and learning experiences tailored to the county level. Communities of Practice [19], referring to learning communities formed through shared practice and interaction, emphasizing contextual learning and knowledge sharing. This can be applied to facilitating knowledge transfer through the construction of teacher professional communities, corresponding to Beijing’s “citywide research and development.” Sociocultural Theory [20] emphasizes the core role of social interaction and cultural tools in individual cognitive development, influencing education and psychology. It also emphasizes the support of ZPD and Scaffolding, guiding Henan in designing localized learning scaffolds.

4. Methodology

This study employs qualitative research, primarily because the research question focuses on “how to localize,” which requires a deep deconstruction of the contextualized meaning of policy implementation to reveal informal adaptation strategies at the grassroots level [21]. Additionally, the transplantation of educational models involves complex contextual negotiations, and quantitative data cannot capture the disconnect between theory and practice. This study adopts Critical Policy Ethnography as its methodological framework. Critical Policy Ethnography is a research paradigm that integrates critical theory with ethnographic methods. It focuses on the practical process of policies in specific social contexts, uncovers the gap between policy texts and their real-world implementation, and reveals the underlying power structures and social inequalities. Due to the short duration of this study, it was not possible to conduct field research or interviews with individuals. Therefore, the paper could only analyze secondary data and obtain subjective data through online questionnaires. This study captures the meaning-making process of Henan educators in policy implementation and explores their localized practices of the Beijing model through a critical ethnographic framework.

5. Data collection & analysis

The data collection for this study was divided into two parts. On the one hand, this study collected some statistical data from recent years. On the other hand, a rapid online survey was administered to gather subjective data regarding the status of secondary education among students in the two regions.

5.1. Secondary data

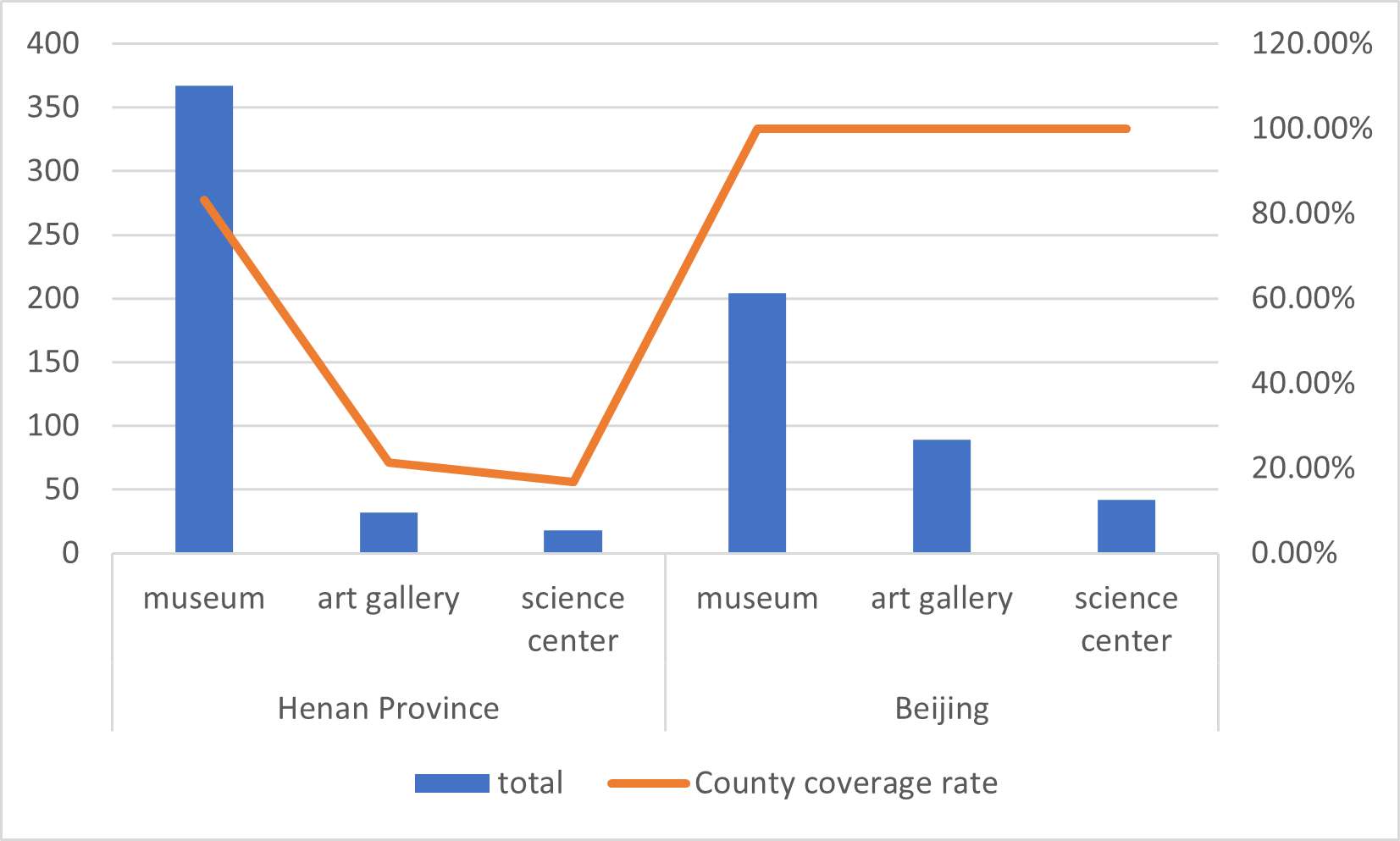

First of all, I collected data on the number of cultural facilities (such as museums and art galleries) in Beijing and Henan, as well as other indicators, to understand whether infrastructure was a major reason why students in Henan were unable to develop comprehensively.

From Figure 2, we can see that the number of art gallery and science center in Henan Province is lower than that in Beijing, and the county-level coverage rate of cultural facilities is also lower than that in Beijing; Although the number of museums is higher than in Beijing, 45% of them are concentrated in the provincial capital Zhengzhou, with the remainder primarily located in more developed cities. In contrast, prefecture-level cities such as Zhoukou and Shangqiu have only 2-3 museums each. Additionally, the low county-level coverage rate indicates that some county towns or rural areas lack museums or similar cultural facilities, forcing students to travel several hours to reach the nearest cultural institution.

In addition, this paper analyzed this data in greater depth. Eighty percent of county-level museums in Henan Province are small to medium-sized museums, and 37% do not have digital exhibition equipment, while 100% of museums in Beijing are equipped with VR/AR education systems. This phenomenon highlights the quality gap between museums. At the same time, 92% of venues in Beijing have signed course cooperation agreements with schools, such as the National Museum’s “Chinese History in Cultural Relics” program in Haidian (a district of Beijing, renowned for its excellent education) classrooms. This directly promotes the development of practical activities for primary and secondary school students; in contrast, only 12% of county-level museums in Henan Province have developed primary and secondary school courses. This demonstrates the maturity of Beijing’s educational model, while Henan Province’s cultural facilities have weaker educational functions.

Secondly, This study researched the implementation of the “5-Dimension Education” model in Beijing, specifically the type of education that Beijing students receive as part of their comprehensive development, and analyzed whether its practices could be applied in Henan Province.

After investigation, Beijing has a mature system of practical activities, with a 100% implementation rate.

|

type |

frequency |

Example |

|

social practice |

Primary school: ≥ 4 times per year |

Experience of Restoring Forbidden City Cultural Relics |

|

High school: ≥ 6 times per year |

Programming in the AI Laboratory |

|

|

Labor volunteer activities |

At least 2 hours per week |

Agricultural learning base cultivation |

|

community voluntary service |

||

|

Educational Travel |

middle school: At least once |

Yan'an Red Culture Study Tour (History Integration) |

|

Ecological Investigation in Inner Mongolia (Geographical Integration) |

|

Participation rate |

Distribution of club types |

average daily time |

|

95.80% |

Science & Technology 32% |

86 minutes |

|

Art 41% |

||

|

89.30% |

Subject extension 28% |

72 minutes |

|

Sports Specialization 37% |

||

|

76.50% |

academic competition 45% |

64 minutes |

|

Volunteer Services 22% |

From Table 1&2, we can see that the Beijing education model places great emphasis on students’ development in extracurricular activities such as clubs. In addition, junior high school students in Beijing spend an average of 1.9 hours per day completing homework, while students in rural areas of Henan Province spend 3.8 hours. The double reduction policy is implemented simultaneously, prohibiting schools from scheduling classes in the afternoon after the regular curriculum is completed, ensuring that after-school time can be used by students for club activities or practical activities. These measures ensure that students can participate in their club activities rather than being forced to spend their time on mandatory cultural homework exercises. Furthermore, in Beijing, students’ comprehensive qualities are factored into their assessment scores, with comprehensive quality evaluations accounting for 30% of the total middle school entrance exam score. These evaluations include dimensions such as practical activities, labor education, volunteer services, and club performance, and these scores can significantly influence their academic advancement.

Compared to the data from Henan Province, this paper find out the key differences between Beijing and Henan: the per-student annual budget for extracurricular activities in Beijing’s urban areas is 623 yuan, while in Henan’s rural counties, it is only 38 yuan per student per year. Beijing schools have a 100% labor education base ownership rate, meaning every school has access to a labor education base, whereas in Henan Province, only urban schools or county-level central schools have such bases. Since labor education is included in evaluations, Beijing middle school students have a volunteer service participation rate as high as 92%, while Henan Province students only have a 21% rate. According to a simple online survey, much of this volunteer service consists of superficial cleanup activities, yielding limited educational benefits.

5.2. Firsthand interview data

In terms of online research, I selected participants based on the following criteria: five students from county secondary schools in Henan Province and five students from The High School Affiliated to Renmin University of China in Beijing. I contacted them and conducted interviews, asking questions orally and having them respond. The questions included:

1. How many field trips or study tours did you participate in during your middle school/high school years? How often does the school typically organize outdoor experiential activities?

2. How many hours of volunteer service did you personally engage in during middle school/high school? Does the school actively arrange for students to participate in volunteer service, or require students to engage in it? How often are such activities organized? What forms do these volunteer services take?

3. Does the school organize club activities or competitions? Does the school generally encourage students to participate in artistic performances or sports competitions? What are the formats of these activities?

4. What percentage of students’ school time is occupied by academic courses? Are there any other enrichment courses besides academic subjects?

The purpose of these questions is comprehensive and clear. I aim to summarize subjective data based on the school’s management practices and the conduct of various activities. These questions address the school’s emphasis on extracurricular activities and whether the school can organize diverse and effective extracurricular activities under various factors.

Through a survey of students in Beijing, I obtained the following information: Excluding special circumstances during the pandemic that prevented field trips, students in junior high and high school each have at least one field trip outside Beijing lasting approximately five days. Practical activities are generally held once per semester, divided into visits to museums/memorial halls/science centers, or trips to scenic spots. During their middle school years, students are required to accumulate a certain number of volunteer service hours before graduation, and schools also organize volunteer activities for students, such as elderly care activities at nursing homes or serving as staff at science exhibition halls. Schools arrange various clubs, including those focused on art, sports, academics, or even entertainment, and frequently hold club performances. They also organize choir performances, festival performances, and sports competitions between classes, aiming to involve as many students as possible in these activities. Due to the policy of reducing academic workload, school classes typically end around 4:00 PM, and if there are regular exams, they do not exceed 5:30 PM. On Thursdays or Fridays, schools may offer some experiential learning courses, which are typically extracurricular activities such as learning minor languages, expanding historical knowledge, conducting chemistry and biology experiments, robotics, and driving simulations.

In contrast, the situation for students in county-level schools in Henan is not optimistic. Most urban schools in Henan conduct field study activities, but the county-level schools they attend do not participate in field study programs in other provinces, and even during the semester, they rarely organize practical activities at nearby scenic spots or science popularization venues. Their schools do not require volunteer activities, so students have little exposure to such initiatives. County-level schools organize county-level sports competitions and artistic performances, but due to the high level of these events, they do not conduct lower-level intra-school competitions, leaving most sports enthusiasts unable to participate. Most importantly, their schools adopt a semi-military management style. After high school, students mostly live on campus, returning home on average once every two weeks. Cultural studies classes are also held on Saturdays, and there are mandatory evening study sessions and morning reading/exercises on weekdays. The number of extracurricular enrichment courses is limited, and no fixed system has been established.

6. Findings

By analyzing this data, this paper draw several results:

Educational policies in county-level schools across Henan Province reveal significant implementation gaps, with the core contradiction lying in the misalignment between resource allocation and institutional incentives. Although county schools formally adopted the Beijing model’s interdisciplinary curriculum framework, severe shortages of specialized teachers often result in these courses being replaced by self-study periods or practice sessions for core subjects in actual teaching. This has led to a situation where curricula exist on paper but lack practical implementation. More concerning is the widespread adoption of a dual-track operational mechanism: schools present policy-compliant timetables during education department inspections while daily instruction strictly follows exam-oriented arrangements. This institutionalized performance behavior validates the core warning of policy transfer theory: when resource foundations and policy objectives are severely misaligned, formalistic implementation inevitably exacerbates educational inequality.

The imbalance in time resource allocation exposed by Henan’s county-level education ecosystem has evolved into systemic oppression. The extreme phenomenon of students spending an average of 12.6 hours daily on studies starkly contrasts with Beijing’s reasonable average of 1.9 hours. This 564% increase in time investment yields only marginal academic gains. More alarmingly, extracurricular participation rates hover below 17%, creating a vast chasm compared to Beijing’s 89% engagement rate. The systemic roots of this problem stem from three pressures: schools extend effective learning time by compressing holidays (reducing them by an average of 21 days) and conducting intensive weekend tutoring; 70% of county-level education budgets are directly tied to college admission rates; and parents, driven by the belief that “arts and sports will hinder core subject performance” (shared by 72% of respondents), form a collusive structure. This distorted resource allocation vividly illustrates DiMaggio’s theory of “coercive isomorphism” [7]: resource-deprived environments are forced to substitute educational quality with time investment.

The gap in cultural and educational resources between urban and rural areas creates a structural bottleneck for quality education. Museum resource allocation exhibits spatial deprivation. County-level museum coverage in Henan Province is less than one-fifth of Beijing’s, with 80% being small-to-medium-sized museums lacking digital exhibition capabilities. More critically, only a handful of venues have developed K-12 curricula, effectively paralyzing the educational function of cultural facilities. Hardware shortages directly lead to systemic disparities in practical activities. Beijing students benefit from a comprehensive system featuring inter-provincial field trips each semester, 100% coverage of labor education bases, and 92% volunteer participation rates. In contrast, county-level students in Henan can only engage in sporadic club activities, labor education bases are restricted to county-level central schools, and volunteer participation rates stand at a mere 21%. This distorted resource allocation further exacerbates inequality: 45% of museums are concentrated in Zhengzhou, leaving students in prefecture-level cities like Zhoukou stranded in cultural deserts.

Henan’s unique local educational resources have long been undervalued in the province’s school teaching models. Despite 90% of schools being adjacent to farmland, which provides natural laboratories for labor education, the extremely low rate of agricultural curriculum development exposes the failure of resource conversion mechanisms. Only 13% of intangible cultural heritage, such as Henan opera, has entered school curricula, and the lack of course design hinders pathways for cultural capital accumulation. A deeper cognitive distortion surfaces when students report that parents complain about field measurements, mirroring the harsh reality of Bourdieu’s cultural capital theory [2]: rural practices unrecognized by certification systems are dismissed by parents as “non-productive” and worthless activities. This dual predicament of resource idleness and cognitive devaluation ultimately reduces labor education to mere “classroom cleaning.”

7. Discussion

The key findings of this study point to a possible way out of the current predicament: rather than simply imitating the Beijing model, the administrators should reconstruct its core concepts, such as comprehensive development, competency-based education, and diversified evaluation, in line with the actual situation in Henan. They should also make full use of Henan’s unique but underestimated resource endowments to seek innovative solutions within the existing economic constraints.

7.1. Curriculum restructuring

The key to breaking the deadlock in Henan lies in abandoning Beijing’s facilities and resources and instead tapping into idle local resources. Research has found that most county schools are adjacent to farmland but rarely develop agricultural courses; intangible cultural heritage such as Henan opera is only introduced into schools for performance and display, without forming a chain of cognitive exploration. This requires:

Labor education in real-world settings: Transform farmland and traditional workshops (such as Yuzhou Jun porcelain and Huaiyang clay figurines) into specialized laboratories and design interdisciplinary projects. For example, in major grain-producing areas, conducting “Exploration of the Wheat Life Cycle and Water-Saving Irrigation Techniques,” which integrates knowledge applications from biology, geography, and other subjects, or launching “Traditional Pattern Digital Design and Marketing” in intangible cultural heritage heritage sites, which connects mathematics, art, information technology, and other subjects, using real-world problems to drive knowledge integration.

Localization of aesthetic and moral education: Develop county-level curriculum packages with low entry barriers but broad coverage. For example, utilize local red sites (revolutionary memorial halls) and folk customs (Baofeng Ma Street Book Fair) to develop an “oral history collection” project, or analyze dialect phonetic patterns through Henan opera excerpts. Such practices do not require expensive equipment but can help rural students accumulate alternative cultural capital.

Specifically, during implementation, it is essential to avoid transforming local courses into elite competitions (such as selecting outstanding students from special courses) and instead focus on the foundational participation of all students (such as collective farming of responsibility fields or group singing of Henan Opera excerpts), ensuring that the five-education activities are not stratified due to economic disparities.

7.2. Evaluation reform

The provincial unified examination has deeply entrenched a single-minded focus on knowledge points and the allocation of county-level resources, which are tightly linked to admission rates. This is the root cause of courses not being implemented as scheduled and activities becoming formalized. The policy requires that the high school entrance exam evaluation incorporate Henan’s distinctive quality assessment framework, initially assigning a 15% weighting to comprehensive quality evaluation, with a focus on recording three quantifiable, fraud-resistant local practices: Basic labor participation, such as maintaining campus responsibility zones, keeping records of family gardening, and ideally engaging in volunteer activities like mandatory farm labor that align with Henan’s local characteristics. Contributions to local projects, such as initiatives to protect intangible cultural heritage in communities or designing water-saving schemes. Daily self-directed time guarantees, monitoring compliance with homework duration regulations to prevent schools from using elective class time for core subjects.

This initiative aims to send a clear signal to parents. for example, the investigative skills demonstrated by Zhoukou students participating in the “Taihao Ling Cultural Exploration” program hold equal evaluative value with Zhengzhou students’ museum course reports, thereby alleviating parents’ widespread anxiety that “music, art, and physical education hinder core subject learning.”

7.3. Mechanism innovation

The most profound crisis in Henan’s education system lies in the inter-school “prisoner’s dilemma”. schools are forced to compete for admission rates by compressing holidays and extending students’ daily study hours, creating a vicious cycle of severe internal competition. Breaking this cycle requires dual-track intervention at the provincial level:

Rigid guarantees for class hours and supervision: Legislation must require all junior high schools to ensure ≥4 class hours per week for non-academic activities, including physical education, aesthetic education, local practice, and clubs. It is strictly prohibited to encroach on non-academic activity time through evening self-study or exams, and weekend tutoring must be resisted. Violations such as early school openings or delayed vacations must be strictly investigated. Establish provincial-level routine inspections and an anonymous parent reporting platform to severely punish violations of the curriculum schedule, expose offenders, and reduce funding allocations.

Decouple resource allocation from competition: Remove the sole reliance on admission rates in county-level education budgets, and instead incorporate metrics such as “implementation rate of the five-education curriculum”, “average daily self-study time for students”, and “contribution to resource sharing for underprivileged schools” as part of the evaluation criteria. Implement the “County-Level Educational Symbiosis” program, requiring key schools within cities to open labor bases and provide teacher support to rural schools, and incorporate the effectiveness of such support into the evaluation and assessment of key schools to prevent resource monopolization from exacerbating inequality.

Only by ensuring that all schools reduce the academic burden simultaneously through provincial-level enforcement can individual schools’ concerns about academic performance declines due to burden reduction be alleviated, enabling teachers to shift from “test-driven teaching” to local curriculum design. After several years of iteration, Henan’s distorted educational practices will be improved.

7.4. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. These limitations pertain to data collection, methodological implementation, and the scope of the research.

First, the research timeline and sample characteristics affect the depth and universality of the subjective data. Due to time constraints, only ten students participated in the study. The small sample size and limited geographic coverage do not capture the full variation within Henan Province or reflect the diversity of student experiences across different school types. Data collection relied exclusively on online questionnaires and interviews. Without face-to-face interaction, the study could not explore nuanced viewpoints through follow-up questions. For example, the specific reasons why parents view labor education as unproductive or the strategies teachers use to adapt elective courses remain unclear. These shortcomings reduce the richness of the qualitative data and oversimplify the complexity of the local educational environment.

Second, the use of secondary data led to issues with timeliness and detail. The study drew on macro-level statistics from various sources and time periods, including reports on private education in Henan [10], unsystematic data on cultural facilities in Beijing and Henan, and policy documents from different years. This resulted in inconsistencies in the time frames used for comparative analysis. Moreover, such data lacks micro-level dynamics. It does not reflect real-time changes or temporary shifts in activity funding due to local policy updates. This restricts the study’s capacity to pinpoint gaps in resource allocation or track how policy implementation evolves over time.

Third, the research design did not fully apply the critical policy ethnography approach, which limited the analysis of informal policy practices. This method typically requires in-depth fieldwork, such as classroom observations and discussions with teachers and administrators, to reveal underlying dynamics. For instance, how teachers adjust Beijing’s interdisciplinary curricula to local conditions or how school leaders negotiate exam pressures with education bureaus remain unexplored. Without field research, this study could only infer such practices from secondary sources and brief online surveys, missing the fine-grained insights needed to understand the micro-level mechanisms of policy localization.

Fourth, the study’s scope does not account for variations within Henan or comparisons with other provinces, which affects the broader applicability of its conclusions. It focuses mainly on comparing county-level schools in Henan with model schools in Beijing, overlooking significant internal disparities. Examples include the resource differences between developed areas like Zhengzhou and less developed regions such as Zhoukou, or variations between urban and rural schools within the same county.

8. Conclusion

This study shows that directly transplanting Beijing’s educational model to Henan is not feasible, given major differences in resources, institutional drivers, and cultural settings. Instead, Henan should pursue a localized strategy that reforms evaluation mechanisms and resource allocation while fully leveraging unique local assets such as agricultural landscapes and intangible cultural heritage. By embedding the core ideas of holistic education into adapted practices, Henan can begin to reduce educational inequality and support students’ comprehensive growth. This paper offers a preliminary framework for localized implementation, stressing that policies must be tailored, not copied. Future efforts should focus on empirical testing and involving stakeholders to refine and effectively apply these approaches.

References

[1]. Henan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. (2025, May 20). Henan Provincial Census Yearbook [PDF]. Author. Retrieved from https: //xcoss.henan.gov.cn/typtfile/20250520/cad9dec7314a4754b0cb99428b82793d.pdf

[2]. Bourdieu, P. (1977). The economics of linguistic exchanges. Social Science Information, 16(6), 645–668. https: //doi.org/10.1177/053901847701600601

[3]. State Council of China. (2019). China Education Modernization 2035. Retrieved from http: //www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-02/23/content_5367987.htm

[4]. Beijing Municipal Education Commission. (2022). Beijing educational reform plan 2022–2025. Retrieved from http: //jw.beijing.gov.cn

[5]. Dolowitz, D., & Marsh, D. (1996). Who Learns What from Whom: A Review of the Policy Transfer Literature. Political Studies, 44(2), 343–357. https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00334.x

[6]. Steiner‐Khamsi, G. (2010). The politics and economics of comparison. Comparative Education Review, 54(3), 323–342. https: //doi.org/10.1086/653047

[7]. DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The Iron Cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147. https: //doi.org/10.2307/2095101

[8]. Zhang, J. (2022). Cultural Capital at the Grassroots Level: An Ethnographic Study of Rural Education. China Social Sciences Press.

[9]. Blake, J. (1981). Family size and the quality of children. Demography, 18(4), 421–442. https: //doi.org/10.2307/2060941

[10]. Hu, D., Yang, X., & Wang, J. (2022). Henan private education development report (2022). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

[11]. Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. In J. T. Roberts, A. B. Hite, & N. Chorev (Eds.), The globalization and development reader: Perspectives on development and global change (2nd ed., pp. 525–548). Wiley-Blackwell.

[12]. Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (1998). What is backward design. Understanding by design, 1, 7-19.

[13]. Jensen, A. R. (1969). How much can we boost IQ and scholastic achievement? Harvard Educational Review, 39(1), 1-123. https: //doi.org/10.17763/haer.39.1.l3u15956627424k7

[14]. Dolowitz, D. P., & Marsh, D. (2000). Learning from Abroad: The Role of Policy Transfer in Contemporary Policy‐Making. Governance, 13(1), 5–23. https: //doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00121

[15]. Walker, J. L. (1969). The Diffusion of Innovations among the American States. American Political Science Review, 63(3), 880–899. https: //doi.org/10.2307/1954434

[16]. Acharya, A. (2004). How ideas spread: Whose norms matter? Norm localization and institutional change in Asian Regionalism. International Organization, 58(02). https: //doi.org/10.1017/s0020818304582024

[17]. Miller, R. (1990). Beyond reductionism: The emerging holistic paradigm in education. The Humanistic Psychologist, 18(3), 314–323. https: //doi.org/10.1080/08873267.1990.9976898

[18]. Gardner, H. (1983). Artistic Intelligences. Art Education, 36(2), 47–49. https: //doi.org/10.1080/00043125.1983.11653400

[19]. Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Learning in doing: Social, cognitive, and computational perspectives. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation, 10, 109-155.

[20]. Sutton, M. & Levinson, B. A. U. (Eds.). (2001). Policy as Practice: Toward a comparative sociocultural analysis of educational policy. Sociocultural studies in educational policy formation and appropriation (329 pp.). Ablex Publishing, an imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., 88 Post Road West, Westport CT 06881 (hardbound: ISBN-1-56750-516-3, $86.95; paperbound: ISBN-1-56750-517-1, $31.95).

[21]. Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes (Vol. 86). Harvard University Press. https: //doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4

Cite this article

Shen,Z. (2025). Optimization of Henan Province’s Education System: A Cultivation Plan for Students’ All-Around Development Based on Beijing’s Education Model. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,114,14-26.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on International Law and Legal Policy

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Henan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. (2025, May 20). Henan Provincial Census Yearbook [PDF]. Author. Retrieved from https: //xcoss.henan.gov.cn/typtfile/20250520/cad9dec7314a4754b0cb99428b82793d.pdf

[2]. Bourdieu, P. (1977). The economics of linguistic exchanges. Social Science Information, 16(6), 645–668. https: //doi.org/10.1177/053901847701600601

[3]. State Council of China. (2019). China Education Modernization 2035. Retrieved from http: //www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-02/23/content_5367987.htm

[4]. Beijing Municipal Education Commission. (2022). Beijing educational reform plan 2022–2025. Retrieved from http: //jw.beijing.gov.cn

[5]. Dolowitz, D., & Marsh, D. (1996). Who Learns What from Whom: A Review of the Policy Transfer Literature. Political Studies, 44(2), 343–357. https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00334.x

[6]. Steiner‐Khamsi, G. (2010). The politics and economics of comparison. Comparative Education Review, 54(3), 323–342. https: //doi.org/10.1086/653047

[7]. DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The Iron Cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147. https: //doi.org/10.2307/2095101

[8]. Zhang, J. (2022). Cultural Capital at the Grassroots Level: An Ethnographic Study of Rural Education. China Social Sciences Press.

[9]. Blake, J. (1981). Family size and the quality of children. Demography, 18(4), 421–442. https: //doi.org/10.2307/2060941

[10]. Hu, D., Yang, X., & Wang, J. (2022). Henan private education development report (2022). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

[11]. Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. In J. T. Roberts, A. B. Hite, & N. Chorev (Eds.), The globalization and development reader: Perspectives on development and global change (2nd ed., pp. 525–548). Wiley-Blackwell.

[12]. Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (1998). What is backward design. Understanding by design, 1, 7-19.

[13]. Jensen, A. R. (1969). How much can we boost IQ and scholastic achievement? Harvard Educational Review, 39(1), 1-123. https: //doi.org/10.17763/haer.39.1.l3u15956627424k7

[14]. Dolowitz, D. P., & Marsh, D. (2000). Learning from Abroad: The Role of Policy Transfer in Contemporary Policy‐Making. Governance, 13(1), 5–23. https: //doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00121

[15]. Walker, J. L. (1969). The Diffusion of Innovations among the American States. American Political Science Review, 63(3), 880–899. https: //doi.org/10.2307/1954434

[16]. Acharya, A. (2004). How ideas spread: Whose norms matter? Norm localization and institutional change in Asian Regionalism. International Organization, 58(02). https: //doi.org/10.1017/s0020818304582024

[17]. Miller, R. (1990). Beyond reductionism: The emerging holistic paradigm in education. The Humanistic Psychologist, 18(3), 314–323. https: //doi.org/10.1080/08873267.1990.9976898

[18]. Gardner, H. (1983). Artistic Intelligences. Art Education, 36(2), 47–49. https: //doi.org/10.1080/00043125.1983.11653400

[19]. Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Learning in doing: Social, cognitive, and computational perspectives. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation, 10, 109-155.

[20]. Sutton, M. & Levinson, B. A. U. (Eds.). (2001). Policy as Practice: Toward a comparative sociocultural analysis of educational policy. Sociocultural studies in educational policy formation and appropriation (329 pp.). Ablex Publishing, an imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., 88 Post Road West, Westport CT 06881 (hardbound: ISBN-1-56750-516-3, $86.95; paperbound: ISBN-1-56750-517-1, $31.95).

[21]. Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes (Vol. 86). Harvard University Press. https: //doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4