1. Introduction

Social media use has increased dramatically in recent decades. This rapid exposure rase concerns about its potential impact on adolescents’ brain development [1]. As an integral component of cognitive process, memory is needed for individuals to construct personal identity, language acquisition, and even develop social relationships [2]. Past research has examined brain regions that control memory and attention and found that social media has altered the brain structure [3]. Hence, it is important to explore the effect of social media on our memory function.

Social media impact memory through multi-dimensional interactive processes, including several cognitive functions such as emotion, attention, and information retrieval. Findings show that increased daily social media use led to more frequent memory failures, especially on emotionally negative days [4]. Another study also shows that sharing experiences on social media reduced memory precision, with participants performing worse on recall tasks compared to those who did not share [5]. These findings collectively point to a core issue: social media usage habits may be reshaping adolescents' memory processing and consolidation mechanisms.

However, current research lacks sufficient explanation of the specific cognitive pathways through which social media affects memory, and there is a lack of systematic integration. Therefore, this review aims to systematically organize existing literature and, from an interdisciplinary perspective combining cognitive neuroscience and media psychology, deeply analyze the internal mechanisms by which social media usage influences memory retrieval in adolescents.

This paper will first outline the basic models of memory formation, then explore how addictive design features of social media—such as reward mechanisms and fear of missing out (FoMO)—disrupt normal memory processes. It will then examine the role of neuroplasticity in this process and evaluate key theories and empirical findings, such as the “Google Effect.” By integrating current evidence, this paper seeks to provide a clear theoretical framework for understanding adolescent cognitive development in digital environments and to guide future intervention research.

2. Memory formation process

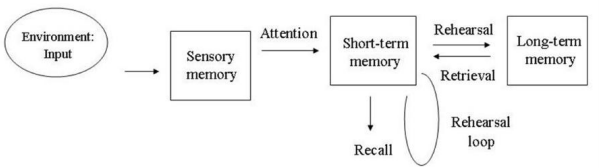

To investigate how memory is affected, it is crucial to understand how it was created first. This multi–store model illustrates the process of how memories are formed. It is divided into three key stages encoding, storage and retrieval [6].

Referring to Figure 1: The Multi-Store Model, encoding is the first step in the memory process. At this stage, environmental input, such as sensory information (e.g., sights, sounds, or smells) is transformed into a format that can be stored by the brain. Once it is encoded, the information enters the sensory memory stage, which typically lasts only a few seconds and holds brief sensory impressions.

Then if you pay attention to the impressions, they could turn into short term memory, with a limited capacity of 7 (+-2) items and a duration of around 20-30 seconds. Short-term memories will enter long-term memory, where it holds the knowledge, experiences, and skills over extended periods, potentially with unlimited storage.

Finally, when we need to use stored information, we engage in retrieval. This can involve recalling information without cues, recognizing it when presented again, or relearning it more quickly the second time [7]. This implies that attention, concentration, and rehearsal are especially important in memory formation and retrieval.

The successful formation and accurate retrieval of memory are highly dependent on the full engagement of cognitive resources, such as attention and the deep processing of information. However, typical patterns of social media use, including frequent task-switching, passive consumption of fragmented content, and constant external notification interruptions, tend to divide users’ attentional resources and promote shallow, automatic modes of information processing. This pattern introduces vulnerabilities during the encoding stage of memory, resulting in weak initial representations of information. Consequently, this undermines the strength of storage in long-term memory and manifests as retrieval difficulties or memory distortions.

These factors are negatively impacting adolescents’ ability to retrieve memories effectively. Therefore, phenomena such as social media addiction, neuroplasticity changes, and the “Google Effect,” which will be explored in the following sections, can all be viewed as mechanisms that interfere with these critical stages of memory formation.

3. Addictiveness of social media

Social media addiction is often classified as a behavioral addiction. The reward system is a major factor contributing to this addiction. Montag et al find when users receive likes or commands for their post, the brain will release dopamine. This neurotransmitter triggers pleasure responses and reinforces compulsive behaviors, which is the same effect that you can gain from cigarettes [8]. Such positive feedback motivates individuals to repeatedly use social media, resulting in addiction.

Another emotional trigger for addiction is the fear of Missing Out (FOMO). As most of social life now has moved online, social media has become a communication platform connecting people all over the world. Able to see others' lives will make people want to follow the trend and naturally feel anxious about being left out. This fear of missing social interactions will result in habitual checking of platforms like Instagram and TikTok [9,10].

Adolescents often have heavy academic and extracurricular demands during these days. So, to make up for their social time they tend to push social media use to nighttime hours. This delay in bedtime reduces both total sleep duration and heightens pre-sleep cognitive arousal, leading to difficult sleep initiations [11]. Late-night screen use suppresses melatonin and disrupts sleep cycles, which are essential for memory consolidation. Research finds that adolescents who use phones after 9 PM have significantly poorer sleep and academic performance [12]. Furthermore, poor sleep quality undermines key cognitive processes, such as memory formation and emotional regulation, which may further intensify stress and dependence on digital platforms for coping [13].

Taken together, these findings suggest that the combination of neurological reward mechanisms, FoMO-driven behaviors, and disrupted sleep patterns works synergistically to increase social media dependence, particularly among adolescents and young adults.

4. Neuroplasticity: the impact of social media on brain structure

As shown in the memory model above, the realization of cognitive functions depends on the structural and functional integrity of specific brain regions. The key to achieving this lies with the inherent neuroplasticity. This refers to the brain’s ability to change its structure and functionality to help people adapt to the environment [14]. Neuroplasticity plays a vital role in cognitive development and learning adaptation, especially in adolescents, whose brains are in a critical period of development. Their brain possesses a high degree of plasticity due to the extremely sensitive neural networks to external stimuli

In the context of social media, information is made to be easily accessible. It is often presented in simple and straight forwards reels (short videos around or less than a minute) [15]. This led to the hypothesis that when people are used to shorter and simpler information, their ability to process complex or long-term information would decrease [16].

Recent research began to examine the intensive use of digital technology and its relation to neuroplasticity. When external factors alter this plasticity can induce adaptive changes in the brain which are associated with cognitive impairment. The findings suggest that the impact of the internet extends beyond just habits and cultural shifts. Even with moderate use, the brain can quickly show signs of physiological changes [17]. For instance, research published in JAMA Pediatrics found that frequent checking of social media platforms over a three-year period was associated with changes in brain regions responsible for social reward processing, such as the amygdala and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; areas crucial for emotional regulation and decision-making [18]. Additionally, Poles reported that exposure to fragmented and fast-paced content on platforms like TikTok and Snapchat can overstimulate cognitive systems, leading to reduced attention span, impaired working memory, and decreased cognitive control [19]. Further evidence from Frontiers in Cognition highlights how constant notifications and multitasking on social media contribute to attentional overload and a state of continuous partial attention, which undermines memory retention and emotional well-being. Noor’s literature review also emphasizes that excessive social media use is linked to deficits in executive functions such as inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility—functions governed by the prefrontal cortex.

A fMRI study shows increased activity in the ventral striatum, and increased ability to tolerate social rewards such as “likes and “comments” people receive from social media [20]. These findings suggest the influence on neurodevelopment patterns. It decreases gray matter density in the prefrontal cortex and results in low attention and impulse control [21].

With the result, excessive digital behavior is seen to enhance visual processing but at the same time impair deep focus and memorization [22]. It facilitated shallow and rapid pattern learning of task-irrelevant, temporally demanding stimuli, people are accustomed to rapid visual recognition and multitasking. However, on the negative side this also reduced working memory capacity and the ability to do deep sustained encoding and retrieval of information.

In general, neuroplasticity offers a biological mechanism through which the social media domain may influence memory retrieval function in adolescents. It allows temporary behavior patterns to become relatively sustainable cognitive patterns.

5. The role of attention distraction and cognitive overload

Beyond social media's direct impact on memory, it can disrupt core cognitive processes. During the formation of memory, storing a sensory memory into long-term needs attention and rehearsal. While this disruption “attention distraction pathway” provides important insights into how social media influences memory processes.

The “Google Effect” theory argues that the internet did not decrease individuals’ ability to memorize information, but rather how it is stored and retrieved. Wang highlights the reliance on digital platforms encourages transactive memory, where users remember where to find information rather than the information itself, leading to weaker internal memory formation [23]. In a study, participants wrote down facts on laptops. Some were told the info would be saved; others weren’t. Some were asked to memorize it; others weren’t. When tested later, those who expected the info to be recorded recalled significantly less, regardless of memorization instructions [24]. This is known as digital amnesia, where people forget content; they assume it is accessible [25]. The human brain naturally thinks in the simplest way, with the least effort [26]. Individuals tend to forget information and unconsciously pay less attention to memorizing information they believe can be easily found online. This change in cognitive approach helps the brain to reduce the effort to store facts [24]. Additionally, Fisher er al revealed that online searchers tend to overestimate their knowledge, which can hinder deeper learning and memory consolidation [27]. These findings suggest that habitual internet use may weaken adolescents’ long-term memory. Achieved through encouraging shallow processing and reducing the need for internal information storage.

6. Conclusion

This review highlights several aspects of the effects social media has had on adolescent cognitive memory. Starting from memory formation processes to cognitive tendencies. Fast content consumption, multitasking, and rewards presented in the form of a variation will disrupt attentional control as well as weaken memory encoding. Other psychosocial motivators, such as FoMO and social validation loops that more strongly reinforce usage patterns, are also to be seen. This is mostly at the cost of both sleep quality and emotional regulation that has important impacts on memory formation.

Adolescence is a critical period of cognitive development. The plasticity-based adaptation of their neuroplastic makes them exquisitely sensitive to environmental input. Long term exposure to fragmented and fast-paced digital content may rewire neural circuits to favor superficial processing rather than deep intellectual engagement, reducing working memory capacity as well as executive function becoming compromised. The “Google effect” theory further indicates the brain’s increasing reliance on the internet as an external memory source. Most people remember where to find information rather than what the content is. This reduces the amount of attention and effort that is applied to sensory memory so that much less will go into long-term memory.

Overall, this review article focuses on the enduring impact of social media in shaping memory architecture and information encoding. These findings underscore the need for interdisciplinary interventions to promote mindful technology use, digital literacy, and cognitive resilience. Future research should consider longitudinal outcomes and explore interventions that can be implemented to help mitigate any cognitive costs of digital immersion, to help adolescents navigate their environments without imposing unwanted costs on their physical and mental health.

References

[1]. Porwal, K., & Sharma, T. K. (2019). Internet addiction and its impact on mental health among adolescents. International Journal of Scientific Research and Reviews, 8(2), 112–118.

[2]. Eysenck, M. W. (2012). Fundamentals of cognition (2nd ed.). Psychology Press.

[3]. Thillay, A., Roux, S., Gissot, V., Carteau-Martin, I., Knight, R. T., Bonnet-Brilhault, F., & Bidet-Caulet, A. (2015). Sustained attention and prediction: Distinct brain maturation trajectories during adolescence. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, Article 519.

[4]. Sharifian, N., & Zahodne, L. B. (2020). Daily associations between social media use and memory failures: the mediating role of negative affect. The Journal of General Psychology, 148(1), 67–83.

[5]. Tamir, M., et al. (2024). Social media makes our memory more fallible. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https: //www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/time-travel-across-borders/202403/social-media-makes-our-memory-more-fallible

[6]. McLeod, S. (2023). Memory stages: encoding storage and retrieval. Simply Psychology. Retrieved from https: //www.simplypsychology.org/memory.html#encoding

[7]. MSEd, K. C. (2024). What is memory? Verywell Mind. Retrieved from https: //www.verywellmind.com/what-is-memory-2795006#retrieval

[8]. Montag, C., Lachmann, B., Herrlich, M., & Zweig, K. (2019). Addictive features of social media/messenger platforms and freemium games against the background of psychological and economic theories. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2612.

[9]. Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848.

[10]. Yang, C. (2016). Instagram use, loneliness, and social comparison orientation: Interact and predict depression. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 486–494.

[11]. Woods, H. C., & Scott, H. (2016). Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem. Journal of Adolescence, 51, 41–49.

[12]. Carter, B., Rees, P., Hale, L., Bhattacharjee, D., & Paradkar, M. S. (2016). Association between Portable Screen-Based Media Device access or use and sleep outcomes. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(12), 1202.

[13]. Vernon, L., Barber, B. L., & Modecki, K. L. (2018). Adolescent problem behavior and sleep quality: The moderating role of gender. Journal of Adolescence, 65, 61–72.

[14]. Puderbaugh, M., & Emmady, P. D. (2023). Neuroplasticity. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. Retrieved from https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557811/

[15]. Duffy, B. E., & Hund, E. (2019). Gendered Visibility on social Media: Navigating Instagram’s authenticity bind. Duffy. International Journal of Communication.

[16]. Haliti-Sylaj, T., & Sadiku, A. (2024). Impact of short reels on attention span and academic performance of undergraduate students. Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 10(3), 60–68.

[17]. Landon-Murray, M., & Anderson, I. (n.d.). Thinking in 140 characters: the internet, neuroplasticity, and intelligence analysis. Digital Commons. University of South Florida.

[18]. Maza, M. T., Fox, K. A., Kwon, S.-J., Flannery, J. E., Lindquist, K. A., Prinstein, M. J., & Telzer, E. H. (2023). Association of habitual checking behaviors on social media with longitudinal functional brain development. JAMA Pediatrics, 177(2), 123–131.

[19]. Poles, A. (2025). Impact of social media usage on attention spans. Psychology, 16(6), 760–772.

[20]. Sherman, L. E., Hernandez, L. M., Greenfield, P. M., & Dapretto, M. (2018). What the brain 'Likes’: Neural correlates of providing feedback on social media. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 13(7), 699–707.

[21]. Montag, C., & Becker, B. (2023). Neuroimaging the effects of smartphone (over-)use on brain function and structure—a review on the current state of MRI-based findings and a roadmap for future research. Deleted Journal, 3.

[22]. NetPsychology. (2025). Neuroplasticity and internet use: How digital life is rewiring our brains. NetPsychology. Retrieved from https: //netpsychology.org/neuroplasticity-and-internet-use-brain-rewiring/

[23]. Wang, Q., & Hoskins, A. (Eds.). (2024). The remaking of memory in the age of the internet and social media. Oxford University Press.

[24]. Sparrow, B., Liu, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science, 333(6043), 776–778.

[25]. Storm, B. C., Stone, S. M., & Benjamin, A. S. (2016). Using the Internet to access information inflates future use of the Internet to access other information. Memory, 24(8), 1113–1121.

[26]. NDTV Health. (2018). Study: Human brains are naturally attracted to laziness.NDTV. Retrieved from https: //www.ndtv.com/health/study-human-brains-are-naturally-attracted-to-laziness-1919396

[27]. Fisher, M., Goddu, M. K., & Keil, F. C. (2015). Searching for explanations: How the Internet inflates estimates of internal knowledge. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(3), 674–687.

Cite this article

Hao,Y. (2025). The Influence of Social Media on Adolescent Cognitive Memory: A Review. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,119,27-32.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICILLP 2025 Symposium: Property Law and Blockchain Applications in International Law and Legal Policy

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Porwal, K., & Sharma, T. K. (2019). Internet addiction and its impact on mental health among adolescents. International Journal of Scientific Research and Reviews, 8(2), 112–118.

[2]. Eysenck, M. W. (2012). Fundamentals of cognition (2nd ed.). Psychology Press.

[3]. Thillay, A., Roux, S., Gissot, V., Carteau-Martin, I., Knight, R. T., Bonnet-Brilhault, F., & Bidet-Caulet, A. (2015). Sustained attention and prediction: Distinct brain maturation trajectories during adolescence. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, Article 519.

[4]. Sharifian, N., & Zahodne, L. B. (2020). Daily associations between social media use and memory failures: the mediating role of negative affect. The Journal of General Psychology, 148(1), 67–83.

[5]. Tamir, M., et al. (2024). Social media makes our memory more fallible. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https: //www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/time-travel-across-borders/202403/social-media-makes-our-memory-more-fallible

[6]. McLeod, S. (2023). Memory stages: encoding storage and retrieval. Simply Psychology. Retrieved from https: //www.simplypsychology.org/memory.html#encoding

[7]. MSEd, K. C. (2024). What is memory? Verywell Mind. Retrieved from https: //www.verywellmind.com/what-is-memory-2795006#retrieval

[8]. Montag, C., Lachmann, B., Herrlich, M., & Zweig, K. (2019). Addictive features of social media/messenger platforms and freemium games against the background of psychological and economic theories. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2612.

[9]. Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848.

[10]. Yang, C. (2016). Instagram use, loneliness, and social comparison orientation: Interact and predict depression. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 486–494.

[11]. Woods, H. C., & Scott, H. (2016). Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem. Journal of Adolescence, 51, 41–49.

[12]. Carter, B., Rees, P., Hale, L., Bhattacharjee, D., & Paradkar, M. S. (2016). Association between Portable Screen-Based Media Device access or use and sleep outcomes. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(12), 1202.

[13]. Vernon, L., Barber, B. L., & Modecki, K. L. (2018). Adolescent problem behavior and sleep quality: The moderating role of gender. Journal of Adolescence, 65, 61–72.

[14]. Puderbaugh, M., & Emmady, P. D. (2023). Neuroplasticity. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. Retrieved from https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557811/

[15]. Duffy, B. E., & Hund, E. (2019). Gendered Visibility on social Media: Navigating Instagram’s authenticity bind. Duffy. International Journal of Communication.

[16]. Haliti-Sylaj, T., & Sadiku, A. (2024). Impact of short reels on attention span and academic performance of undergraduate students. Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 10(3), 60–68.

[17]. Landon-Murray, M., & Anderson, I. (n.d.). Thinking in 140 characters: the internet, neuroplasticity, and intelligence analysis. Digital Commons. University of South Florida.

[18]. Maza, M. T., Fox, K. A., Kwon, S.-J., Flannery, J. E., Lindquist, K. A., Prinstein, M. J., & Telzer, E. H. (2023). Association of habitual checking behaviors on social media with longitudinal functional brain development. JAMA Pediatrics, 177(2), 123–131.

[19]. Poles, A. (2025). Impact of social media usage on attention spans. Psychology, 16(6), 760–772.

[20]. Sherman, L. E., Hernandez, L. M., Greenfield, P. M., & Dapretto, M. (2018). What the brain 'Likes’: Neural correlates of providing feedback on social media. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 13(7), 699–707.

[21]. Montag, C., & Becker, B. (2023). Neuroimaging the effects of smartphone (over-)use on brain function and structure—a review on the current state of MRI-based findings and a roadmap for future research. Deleted Journal, 3.

[22]. NetPsychology. (2025). Neuroplasticity and internet use: How digital life is rewiring our brains. NetPsychology. Retrieved from https: //netpsychology.org/neuroplasticity-and-internet-use-brain-rewiring/

[23]. Wang, Q., & Hoskins, A. (Eds.). (2024). The remaking of memory in the age of the internet and social media. Oxford University Press.

[24]. Sparrow, B., Liu, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science, 333(6043), 776–778.

[25]. Storm, B. C., Stone, S. M., & Benjamin, A. S. (2016). Using the Internet to access information inflates future use of the Internet to access other information. Memory, 24(8), 1113–1121.

[26]. NDTV Health. (2018). Study: Human brains are naturally attracted to laziness.NDTV. Retrieved from https: //www.ndtv.com/health/study-human-brains-are-naturally-attracted-to-laziness-1919396

[27]. Fisher, M., Goddu, M. K., & Keil, F. C. (2015). Searching for explanations: How the Internet inflates estimates of internal knowledge. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(3), 674–687.