1. Introduction

As indicated by World Health Organization (WHO) reports, approximately 1.1 billion people worldwide suffer from mental disorders, of whom more than 280 million live with depression1 [1]. These alarming numbers prompt us to place greater emphasis on mental health, or rather, depression-a clinical picture which goes beyond the mere presence of low mood, but includes markedly low motivation, anhedonia (the capacity to experience pleasure is lost) [2] and most important of all, an overwhelming feeling of hopelessness about the future [3].

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are diverse types of highly stressful or traumatic events occurring before the age of 18. They have been identified as an established risk factor for depression [4]. The effects of early stress and trauma on the psyche persist into adulthood [5], as half of all lifetime mental disorders can be traced to their roots in childhood [5]. Trauma occurs when a person is exposed to overwhelming and unavoidable events that exceed his/her coping resources and lead to high levels of distress and fear [6]. As a public health problem, trauma in childhood presents itself through symptoms such as hypervigilance, avoidance, trauma-related intrusive memories, trauma-related heightened emotional and physiological arousal [7].

While childhood trauma has been consistently established as a significant predictor of depression in adulthood, the precise psychological mechanisms underlying this relationship remain incompletely understood. Of particular relevance is hopelessness—a core component of depressive pathology—which demonstrates robust associations with post-traumatic stress symptomatology [7]. This pattern raises the possibility that hopelessness may function as a critical mediating pathway through which early traumatic experiences contribute to subsequent depressive disorders.

Based on Maier and Seligman's established theory of learned helplessness, early traumatic experiences—particularly persistent emotional or physical neglect and abuse—can be understood as sustained exposure to uncontrollable adverse conditions [8]. Within such environments, young individuals often develop deeply ingrained beliefs of personal inadequacy ("I must deserve this because I'm fundamentally flawed") or a pervasive conviction that their circumstances are unchangeable ("Nothing I ever do matters"). Unlike active mistreatment, emotional and physical neglect operates through omission rather than commission—leaving children feeling unseen, invalidated, and despairing of ever having their core needs recognized. Conversely, direct abuse (whether emotional or physical) systematically dismantles self-worth through explicit denigration, punishment, and rejection, thereby cementing hopelessness.

Abramson, Metalsky, and Alloy's Hopelessness Theory of Depression proposes a causal link to depressive disorders [9]. Central to Beck's cognitive theory is the concept of the cognitive triad [10], which proposes that depressed individuals are characterized by perceptions of worthlessness, a belief that the world is threatening, and an expectation of future failure. Childhood trauma directly shapes the first two (“I am unlovable/incompetent”, “The world is dangerous/indifferent”), while hopelessness is the concentrated manifestation of the “negative view of the future”. Therefore, hopelessness serves as a critical bridge connecting the negative self/world schemas formed by trauma and depressive emotions.

The current study evaluates the mediating role of hopelessness in the childhood trauma-depression pathway. An important and novel hypothesis emerging from this research is that hopelessness plays a central role in the pathway through which diverse types of early adverse experiences lead to depressive outcomes in adulthood. The approach taken in this study differs from other studies that conceptualize childhood trauma as a unitary construct and instead explores whether a similar pathway of hopelessness exists for different trauma subtypes and if so, how would it differ. This study provides a more granular investigation into the psychological profile that follows childhood trauma.

2. Method

The research employed standardized self-report measures to assess specific dimensions of childhood trauma, depressive symptoms, and levels of hopelessness, along with the potential mediation effect of hopelessness.

For the Chinese Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) - a 20-item measure using a 1-5 scoring system (total: 20-100)—score elevation denotes worsening hopelessness. Severity levels are: 0-3 (normal), 4-8 (mild), 9-14 (moderate), >14 (severe). In the study by Kong et al., the scale demonstrated a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.85 and a test-retest reliability of 0.62 (p < 0.001). The total score of the hopelessness scale was positively correlated with the total score of the suicidal ideation scale (r = 0.35, p < 0.001). Reliability analyses from Liu et al. yielded Cronbach's α coefficients of 0.92 and 0.86 for the BHS in the suicide death and normal control groups, respectively.

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) is a prominent self-report instrument for evaluating the severity of depressive symptoms. Developed by Beck in 1996 as a revision of the original BDI, this 21-item measure assesses symptoms over the preceding two-week period in clinical and non-clinical populations. Each item is rated from 0 to 3, producing a total score between 0 and 63 [11].

The Chinese version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF, 28-item) was made available in 2005 by Yao et al. [12], based on the original work of Bernstein and Fink. The 28-item CTQ-SF comprises five subscales: Emotional Abuse (EA), Physical Abuse (PA), Sexual Abuse (SA), Emotional Neglect (EN), and Physical Neglect (PN). Scores meeting or exceeding established thresholds (EA≥13, PA≥10, SA≥8, EN≥15, PN≥10) on any subscale signify moderate-to-severe trauma. The instrument demonstrated good internal consistency in this study, with a Cronbach's α of 0.718 at T1 [12].

This research used SPSS v.29.0.1 to analyze data. The present study examined the linkages between five specific dimensions of childhood trauma (EA, PA, SA, EN, PN) and depression. To elucidate the underlying mechanism, a mediation model was tested with hopelessness as the proposed mediator between each dimension of childhood trauma and depression.

3. Results

This experiment distributed 132 questionnaires and collected 113 valid responses, including 38 from males and 74 from females, with a mean age of 22.

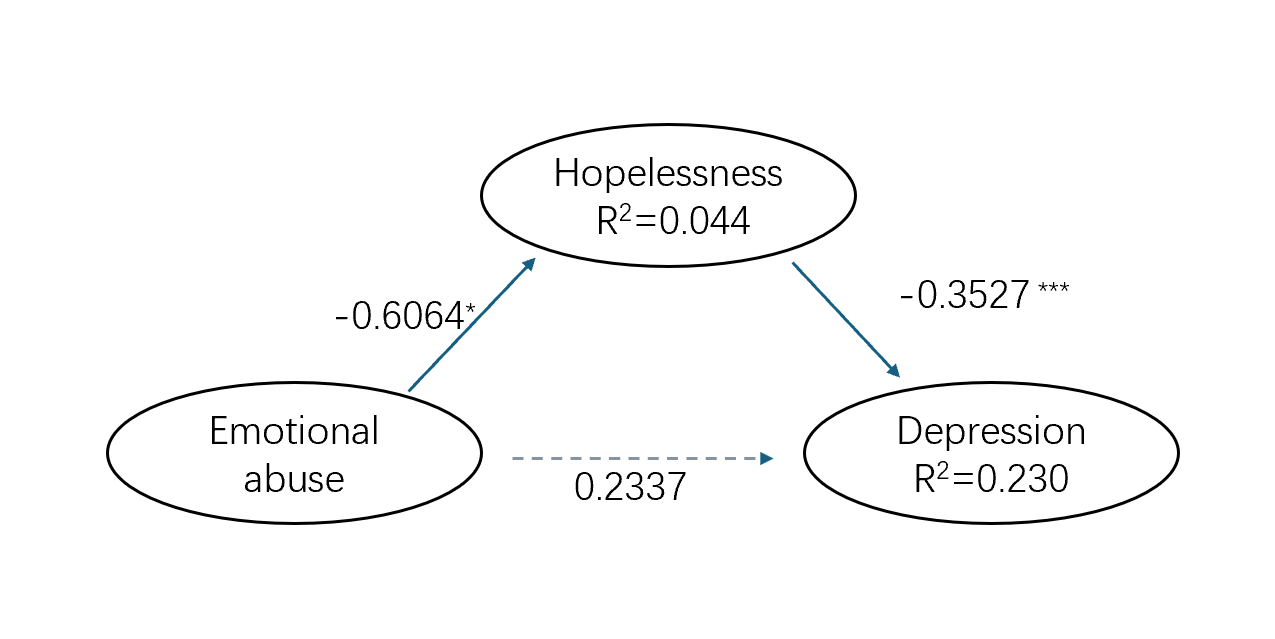

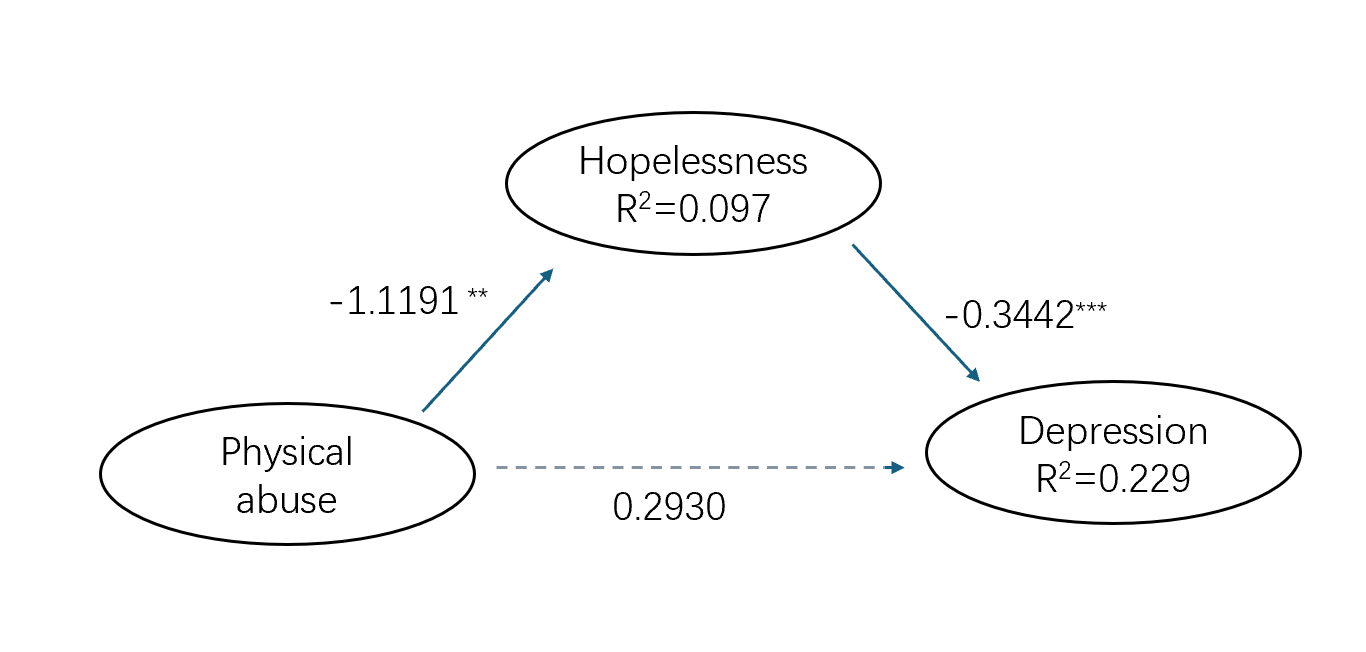

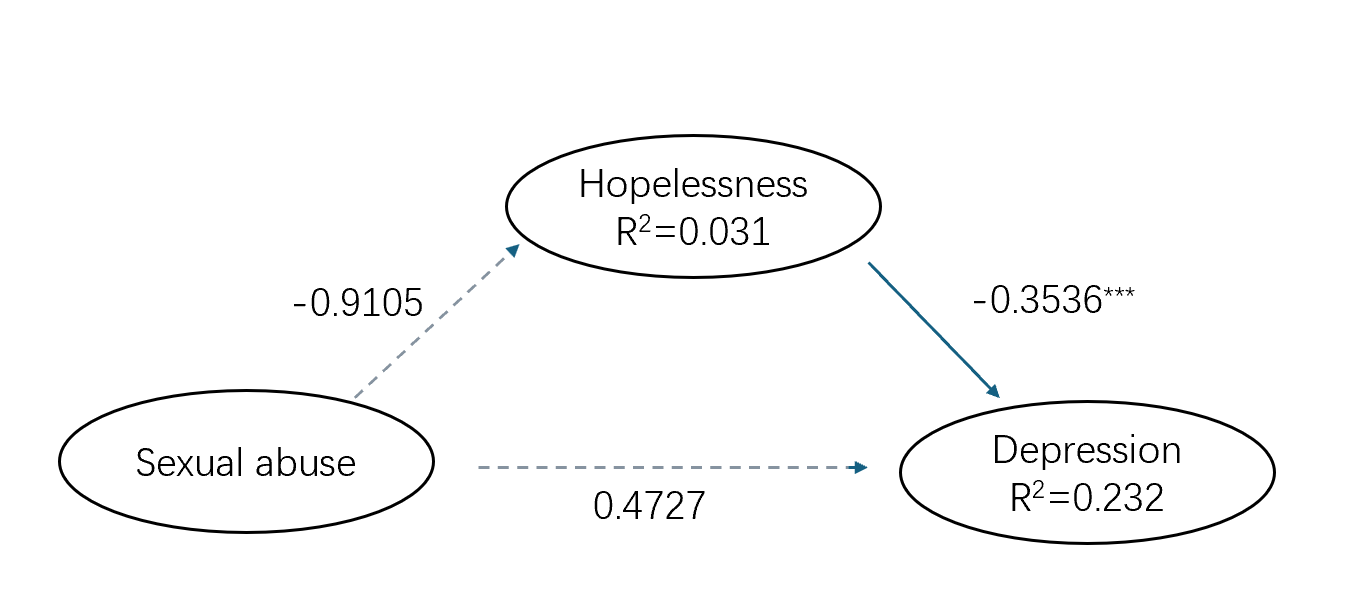

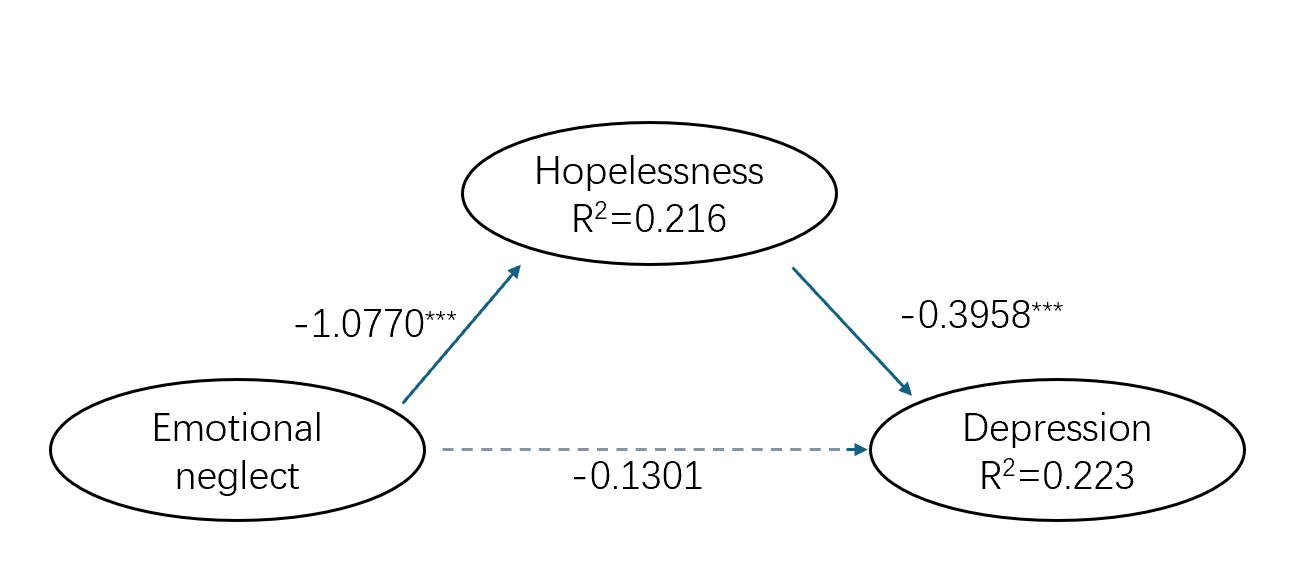

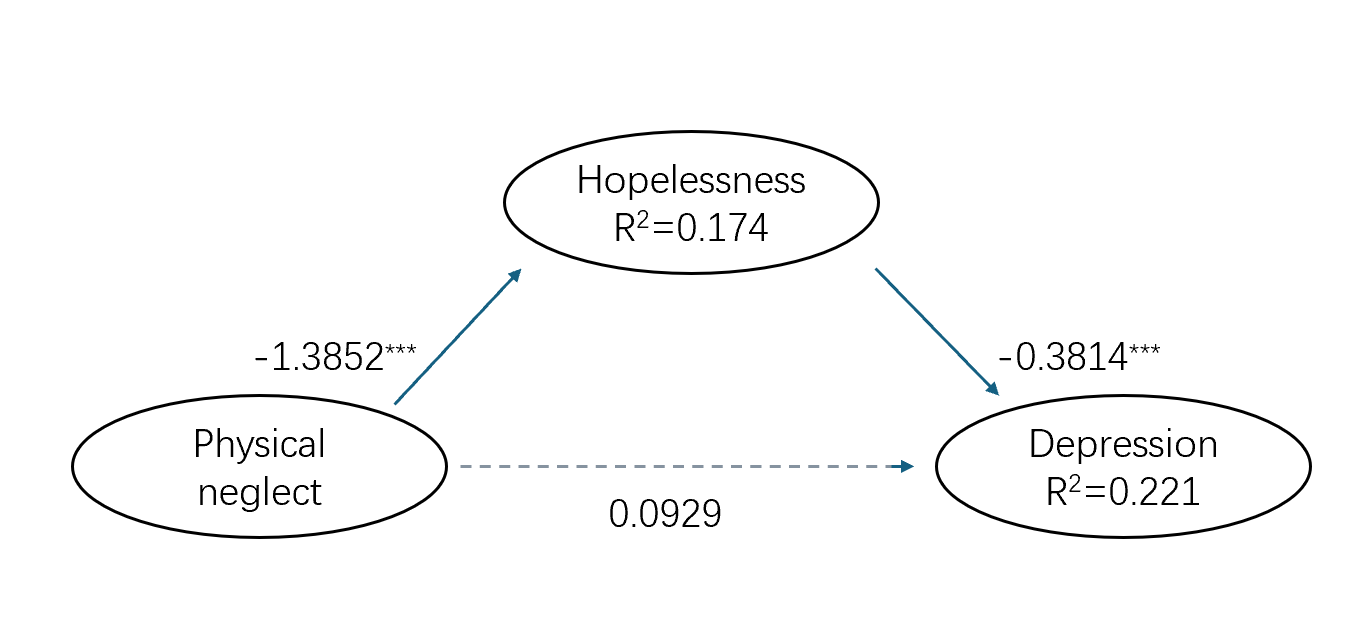

The mediation result is shown in Figure 1 to Figure 5.

ps. The dashed line indicates that the coefficient is not significant. * 0.01<p<0.05,*** p<0.001

ps. The dashed line indicates that the coefficient is not significant. ** 0.001<p<0.01, *** p<0.001

ps. The dashed line indicates that the coefficient is not significant. *** p<0.001

ps. The dashed line indicates that the coefficient is not significant. *** p<0.001

ps. The dashed line indicates that the coefficient is not significant. *** p<0.001

All childhood trauma factors except sexual abuse influence depression through the mediation of hopelessness. Childhood trauma (EA, PA, EN, PN) influences depression through the significant indirect effect of hopelessness, with no direct effect.

4. Discussion

The present findings offer support for our primary hypothesis concerning the mediation role of hopelessness in the pathway between childhood trauma and depression. Our results corroborate Beck's cognitive model of depression and provide support for the psychological pathway through which early adverse experiences lead to enduring psychological distress and morbidity through the establishment of negative schemas. From a clinical perspective, the present findings suggest that greater emphasis should be placed on the inclusion of targeted interventions aimed at hopelessness (Hope Focused Therapy) in the psychotherapy intervention for survivors of trauma. Although the cross-sectional design of the study precludes any causal inference, the mediated effects found in the present study demonstrated large effect sizes that warrant further exploration in a longitudinal design. Future research should also explore the existence of moderating factors such as social support systems that may modify the mediated relationship explored in the current study.

Koçtürk’s [13], Bilginer Asberg’s [14] and Renk’s [15] previous studies have reported no significant relationships with sexual abuse for hopelessness variables consistently. This different pattern may arise from perpetrators’ creation of complex emotional bonds with the help of psychological manipulation techniques, and may lead to the idea that the victims consider the abuse as either a kind of special love [15]. In this regard, it may be possible that the victims think that the perpetrator abuses them in order to gain attention from them or to provide them with security [15]. In this respect, DeYoung and Lowry’s [16] study reported that children who were abused through incest also developed emotional bonds with the abusing father. All of these studies showed that trauma-bonding mechanisms may be the reason for hopelessness’s lack of a mediating relationship between sexual abuse and depression.

On the other hand, as can be seen in Table 3, it is clear that shame takes a place instead of hopelessness and has a significant relationship with depression in terms of sexual abuse (r² = 0.3). [17].

5. Conclusion

In the present study, the relationships between the different types of childhood trauma and adult depression were examined, and the mediating role of hopelessness was emphasized. Our most important finding is that hopelessness takes the role of a basic psychological mechanism that connects EA, PA, EN, and PN to depressive outcomes, and this large pattern is consistent with the learned helplessness model. That is, these particular types of adverse experiences that have a persistent and uncontrollable nature, gradually cause the capacity of the individual to sustain positive future expectations to be lost, and thus create a pathogenic pathway to depression.

Sexual abuse showed a different psychopathological pathway and no significant relationship with hopelessness. This different pattern indicates that different trauma categories may use different psychological pathways in affecting mental health outcomes. In the case of sexual abuse, it seems that there are more explanatory power in other mediating variables than hopelessness in the development of depressive symptoms: strong shame reactions, post-traumatic stress symptomatology, or profound interpersonal difficulties.

Theoretically, this study emphasizes the need for a differentiated look at childhood trauma, which is heterogeneous in itself, to go beyond undifferentiated conceptualizations. From a clinical implementation point of view, the results of this study showed the need for different intervention forms. Cognitive-behavioral protocols targeting hopelessness and helplessness have particular value for survivors of abuse and neglect. On the other hand, treatment of sexual trauma should focus on the trauma resolution related to shame and traumatic memory processing.

Several limitations should be considered when generalizing the findings of this study. The cross-sectional design of the study prevents a definitive conclusion about causality. In addition, because of the narrow age range of the sample, it may not be possible to generalize the results to other populations. In addition, the childhood adverse experiences were retrospectively reported, and there may have been recall bias. It is possible to think that the longitudinal design that will follow the trauma course over time and will include other mechanistic variables in addition to hopelessness and shame, will clarify the different pathways will be better understood, while studying sexual abuse. It is also important to repeat these findings in more diverse clinical populations with larger sample sizes.

This is the first study to offer empirical support for the core hypothesis that hopelessness plays a mediating role in the associations between different types of childhood trauma and later depressive symptoms. By identifying a different psychopathological profile associated with sexual abuse that is distinct from that of other types of abuse, which does not involve hopelessness as a mediating variable, this research offers a refined model for understanding the childhood-predated psychopathology of sexual abuse.

References

[1]. WHO. (2025). Mental Disorders. Retrieved from https: //www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders

[2]. Xiao-Ting Zhou, Wen-Dai Bao, Dan Liu and Ling-Qiang Zhu. (2020). Targeting the Neuronal Activity of Prefrontal Cortex: New Directions for the Therapy of Depression. Current Neuropharmacology: CN, 18(4), 332–346.

[3]. Beck, A. T., Weissman, A., Lester, D. and Trexler, L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(6), 861–865.

[4]. YoungMinds. (n.d.). Understanding trauma and adversity. Retrieved from https: //www.youngminds.org.uk/professional/resources/understanding-trauma-and-adversity/

[5]. Kessler, R.C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K.R. and Walters, E.E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602.

[6]. Minds. (2023). Trauma. Retrieved from https: //www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/trauma/about-trauma/

[7]. Raman, U., Bonanno, P.A., Sachdev, D., Govindan, A., Dhole, A., Salako, O., Patel, J., Noureddine, L.R. and Tu, J., Guevarra-Fernández, J., Leto, A., Nemeh, C., Patel, A., Nicheporuck,

[8]. Maier, S.F., Seligman, M.E. (1976). Learned helplessness: Theory and evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 105(1), 3–46.

[9]. Abramson, L.Y., Metalsky, G.I. and Alloy, L.B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96(2), 358–372.

[10]. Beck, A.T. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press.

[11]. Yuan, G., Zhao, J., Zheng, D. and Zhao, B.Y. (2021). Study on distinguishing the severity of depression with Self-Rating Depression Scale and Beck Depression Inventory. Journal of Neuroscience and Mental Health(12), 868-873.

[12]. Hao, Y. (2024). The Developmental Relationship between Psychological Resilience and Post-traumatic Growth and the Impact of Childhood Trauma among Male Underage Inmates in Hainan Province (Master's thesis, Hainan Medical University)

[13]. Koçtürk, N., Bilginer, Ç. (2022). Sexual abuse, psychological symptoms and hopelessness among runaway female adolescents in Turkey. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 33(3), 461–474.

[14]. Asberg, K., Renk, K. (2014). Perceived stress, external locus of control, and social support as predictors of psychological adjustment among female inmates with or without a history of sexual abuse. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(1), 59–84.

[15]. Gaddes, B.M. (2013). Love’s Rope : the Interpersonal and Intrapsychic Psychodynamics of Child Sexual Abuse [Dissertation, Pacifica Graduate Institute]. Retrieved from https: //www.proquest.com/docview/1376752927

[16]. deYoung, M., Lowry, J.A. (1992). Traumatic Bonding: Clinical Implications in Incest. Child Welfare, 71(2), 165–176.

[17]. Ellenbogen, S., Colin-Vezina, D., Sinha, V., Chabot, M. and Wells, S.J.R. (2018). Contrasting mental health correlates of physical and sexual abuse-related shame. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 30(2), 87–97.

Cite this article

Li,Y. (2025). The Pathway of Hopelessness: Linking Childhood Trauma to Depression. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,119,56-62.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICILLP 2025 Symposium: Property Law and Blockchain Applications in International Law and Legal Policy

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. WHO. (2025). Mental Disorders. Retrieved from https: //www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders

[2]. Xiao-Ting Zhou, Wen-Dai Bao, Dan Liu and Ling-Qiang Zhu. (2020). Targeting the Neuronal Activity of Prefrontal Cortex: New Directions for the Therapy of Depression. Current Neuropharmacology: CN, 18(4), 332–346.

[3]. Beck, A. T., Weissman, A., Lester, D. and Trexler, L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(6), 861–865.

[4]. YoungMinds. (n.d.). Understanding trauma and adversity. Retrieved from https: //www.youngminds.org.uk/professional/resources/understanding-trauma-and-adversity/

[5]. Kessler, R.C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K.R. and Walters, E.E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602.

[6]. Minds. (2023). Trauma. Retrieved from https: //www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/trauma/about-trauma/

[7]. Raman, U., Bonanno, P.A., Sachdev, D., Govindan, A., Dhole, A., Salako, O., Patel, J., Noureddine, L.R. and Tu, J., Guevarra-Fernández, J., Leto, A., Nemeh, C., Patel, A., Nicheporuck,

[8]. Maier, S.F., Seligman, M.E. (1976). Learned helplessness: Theory and evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 105(1), 3–46.

[9]. Abramson, L.Y., Metalsky, G.I. and Alloy, L.B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96(2), 358–372.

[10]. Beck, A.T. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press.

[11]. Yuan, G., Zhao, J., Zheng, D. and Zhao, B.Y. (2021). Study on distinguishing the severity of depression with Self-Rating Depression Scale and Beck Depression Inventory. Journal of Neuroscience and Mental Health(12), 868-873.

[12]. Hao, Y. (2024). The Developmental Relationship between Psychological Resilience and Post-traumatic Growth and the Impact of Childhood Trauma among Male Underage Inmates in Hainan Province (Master's thesis, Hainan Medical University)

[13]. Koçtürk, N., Bilginer, Ç. (2022). Sexual abuse, psychological symptoms and hopelessness among runaway female adolescents in Turkey. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 33(3), 461–474.

[14]. Asberg, K., Renk, K. (2014). Perceived stress, external locus of control, and social support as predictors of psychological adjustment among female inmates with or without a history of sexual abuse. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(1), 59–84.

[15]. Gaddes, B.M. (2013). Love’s Rope : the Interpersonal and Intrapsychic Psychodynamics of Child Sexual Abuse [Dissertation, Pacifica Graduate Institute]. Retrieved from https: //www.proquest.com/docview/1376752927

[16]. deYoung, M., Lowry, J.A. (1992). Traumatic Bonding: Clinical Implications in Incest. Child Welfare, 71(2), 165–176.

[17]. Ellenbogen, S., Colin-Vezina, D., Sinha, V., Chabot, M. and Wells, S.J.R. (2018). Contrasting mental health correlates of physical and sexual abuse-related shame. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 30(2), 87–97.