1. Introduction

Aging had become a prevalent societal issue globally. Data shows that by 2019, China has 254 million elders of 60-years-old and above. By 2040, an estimated 402 million people (28% of the total population) will be over the age of 60 (Ageing and health - China, 2022). [1] As the elderly population increases, societies and the world as a whole must put forward beneficial policies that made the life of the elders more convenient and more inclusive. Such efforts ranged from healthcare systems to relatively trivial aides (e.g., free bus pass in China). While elders are eligible and accessible to societal welfare and benefits, elders today are not immune to prejudice and discrimination.

Such prejudice and discrimination against elders are widely known as ageism, referring to “the systematic stereotyping of and discrimination against people because they are old, just as racism and sexism accomplish this with skin color and gender” [2]. There is possible ageism that comes from different aspects: elders will bring financial burden to a family; they are stubborn and unable to integrate to the modern society. Experiencing ageism may exert significant detrimental effects upon elders in an array of negative social, psychological, and physical outcomes [3].

Some research has found that ageism can be prevalent among the young generation. Nowadays, young adults tend to hold negative stereotypes and attitudes toward older adults [4], which can lead to condescending attitudes that in turn has negative effects on the physical and psychological well-being of older adults [5]. These stereotypical perception or negative impressions about elders mainly derive from the age difference and incompetence in communication accommodation. Being old has often been associated with lower competence and deficiency in providing social resources. Additionally, young adults often feel being patronized when interacting with elders, which in turn further driving these two social groups apart. This perception of low competence in combination to low warmth could result in threatening perception of older adults. When seeing elders as a social threat, ageism arises. Although younger generation often holds hostile and negative attitudes towards older adults, a dearth of knowledge exists regarding attitudes among teenagers, especially in China, where aging issue is rapidly growing in the last decade. From a social contact perspective, this paper surveyed Chinese teens’ attitudes and its association with threats to illustrate the intergenerational relationship in China.

1.1. Social Contact theory

People have an innate need to be affiliated with others. According to social identity theory [6], it is of great importance for individuals to establish positively valued distinctiveness for one’s own group compared to other groups. Individuals are in constant comparison with others to seek for positive distinctiveness. For marginalized and minority group, like elders, they must constantly face the negative attitudes or perceptions (e.g., low competence) attached to their group identity [7]. These tensions between social groups often appear as misunderstanding, prejudices, hostile attitudes, and even discrimination between different groups, which propelled research on possible solutions to ameliorate intergroup relationships.

Social contact theory is one of the most prominent theories in the field. It posits that frequent contact between social groups allows more understanding and friendliness to accept diversity. Close intergroup relationships are particularly powerful in reducing uncertainties and anxieties from intergroup contact and are associated with more positive attitudes toward the outgroup [8]. Future research demonstrates four essential conditions --- equal status, common goals, institutional support, and group collaboration --- are of great importance for the effects of social contact on altering attitudes towards the outgroup members [9]. The meta-analysis conducted by Pettigreew and Tropp (2000) provides further empirical evidence for this theory, which makes it one of the key theoretical frameworks to delve into most intergroup communication problems. Research has confirmed that intergroup anxiety strengthened the relationship between social contact and positive intergroup attitudes because frequent and high-quality social contact could reduce anxiety by further understanding with the outgroup, and chances to establish affective ties with outgroup members; these processes then transfer to positive perceptions of the outgroup [8].

1.2. The Relationship Between Social Contact and Agism

Social contact theory has been applied to the context of intergenerational relationships. Nowadays, owing to the generational gap the contact between young teens and older adults are currently maintaining a poor frequency and low quality. However, as suggested by the social contact theory, frequent intergroup contact is of great significance in terms of intergenerational relationships. Positive interaction across social groups could help group members overcome their exclusiveness and misunderstanding. Studies shows that close intergroup relationships are particularly powerful in reducing uncertainties and anxieties from intergroup contact and are associated with more positive attitudes toward the outgroup [8]. Hence, in the case of young teens and older adults, people should also increase the commonness to form high quality bond to overcome its discrimination. Not only should we focus on their physical convenience from the perspective of public goods, but we should also be aware of their family relationships, and society’s attitudes around them, such as stereotypes. One experiments in Korea, had showed that it is essential to have adequate contact (especially positive contact) between Korean young adults and their grandparents to improve aging attitudes [10]. Therefore, building connection with the surrounding social circles are also an essential solution for reducing intergroup threats, such as agism.

1.3. The Current Study

In this paper, we created an experiment about social media's influence on teen’s perceived ageism and threats towards elders. In particular, to reduce the intergroup threats between young teenagers and elders, we prepared six articles about different elders’ story from different areas and industry to help the participant to increase familiarity about another social group, elders, which they might not have enough knowledge about. For example, one story described how an older adult, Wang YeYe (i.e., YeYe is an endearment in Chinese referring to an older male adult) created a club of traditional Chinese opera particularly for elders. This drama club performs Beijing operas regularly in the nursing homes for elders. The story recorded his journey to launch this club, and his dream for being a Chinese opera singer. More importantly, this story is set to present the elders as a heterogenous group, of which older adults have their own specific hobbies and passions, but also devoted to something that is exciting. Every article had introduced similar stories as Wang YeYe, who are still actively trying to achieve their life goals. These messages about elders are somewhat contradictory to conventional or stereotypical perception of older adults as someone of low competence.

We disseminated these stories on a WeChat official account called ZheZhou (or Furrow in English). WeChat is the most wildly used social media platform in China with billions of active users daily. One of its main functions is called official counts, allowing everyone to create news stories and share their views with a wide range of audiences. Users usually follow some official accounts and then read articles containing both text and images. These messages could provide vivid and fresh perspectives of an often invisible or marginalized group, providing rare opportunities for cross-group interaction through this mediated environment. Currently, we post monthly update on ZheZhou, each of which contains a new story about an older adult living for their passion and dreams. These diver representations of the Chinese elders have reached to 100 active users.

In sum, this study plans to test social contact theory in the context of Chinese elders and teens. Moreover, it aims to investigate to what extent exposure to news stories regarding heterogenous group of older adults will influence teen’s perception of this group. Consideirng this, we propose:

H1: When those Chinese middle schoolers have low intention to contact with Chinese elders, they will show higher level of (a) perceived threats towards these elders and (b) ageism.

H2: For those Chinese middle schoolers who have exposed to stories about elders on WeChat, they will show lower level of (a) perceived threats towards these elders and (b) ageism than those who have not read these stories online.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedures

This study used convenient sampling to recruit middle schoolers (9- to 15-years-old) studying in Beijing. A survey link has been distributed within WeChat groups made up of eligible middle schoolers, advertised as a survey to assess teens’ attitudes towards elders. A total of N = 83 teens participated in this online survey study (a total of 33 girls, Mage = 12.35, SDage = 1.152).

These middle schoolers have been randomly assigned to two conditions: 1) the manipulation condition, where individuals were asked to browse the WeChat account, ZheZhou, for one week (n = 42); 2) control condition, where individuals carry out their regular life as usual without knowing about any of the stories posted on WeChat (n = 41). This manipulation allows us to test whether reading stories about elders will change middle schooler’s perceptions of older adults or not. After one week, all individuals are asked to fill in the same survey measures online as reported below.

2.2. Mesures

2.2.1. Threats

Two questions were asked to assess the elders’ sense of threat towards young children in China: “elderly people in China will have a negative impact on the society and the national economy” and “the Chinese elderly population will bring pressure on the socio- economic development of the younger generation”. Participants are asked to vote for their level of agreement with these two statements with 5-Likert point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree).

2.2.2. Agism

Eight questions were asked to assess children’s agism towards elders in China: “Most older people think differently: I can’t understand them at all,” and “the Chinese elder population will bring pressure on the socio-economic development of the younger generation” etc. Participants are asked to vote for their level of agreement with these eight statements with 5-Likert point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree).

2.2.3. Social Contact

Three questions were asked to assess current young generation’s contact with elders in China: “I will have more contact with the elders,” “I will learn more about the elder’s community” and “I think it's important to have contact with older people in the future” Participants are asked to vote for their level of agreement with these three statements with 5-Likert point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree).

2.3. Results

The first hypothesis proposed a negative relationship between Chinese middle schoolers’ intention to contact with Chinese elders with perceived threats towards these elders and ageism. Correlation analysis was used to investigate relationship among the three main variables within this sample. Table 1 presents the correlation statistics. As it shows in Table 1, there is a negative relationship between intention to contact with elders and perceived threats, r = -.302, p = .006. This means Chinese middle schoolers showed higher level of perceived threats towards Chinese elders, if they did not intend to engage in any contact with Chinese elders. Second, we considered the relationship between ageism and intention to contact. Again, a negative association emerged, r = -.334, p = .002. This means those Chinese middle schoolers who would not like to contact with Chinese elders will show higher level of ageism. These findings support H1.

Table 1: Correlation between perceived threats, agism, and intention to contact with elders.

Variable | Social contact | Threats | Ageism |

1. Social Contact | — | ||

2. Threats | -.302** | — | |

3. Agism | -.334** | 0.211 | — |

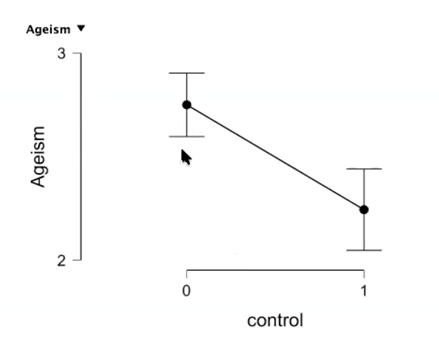

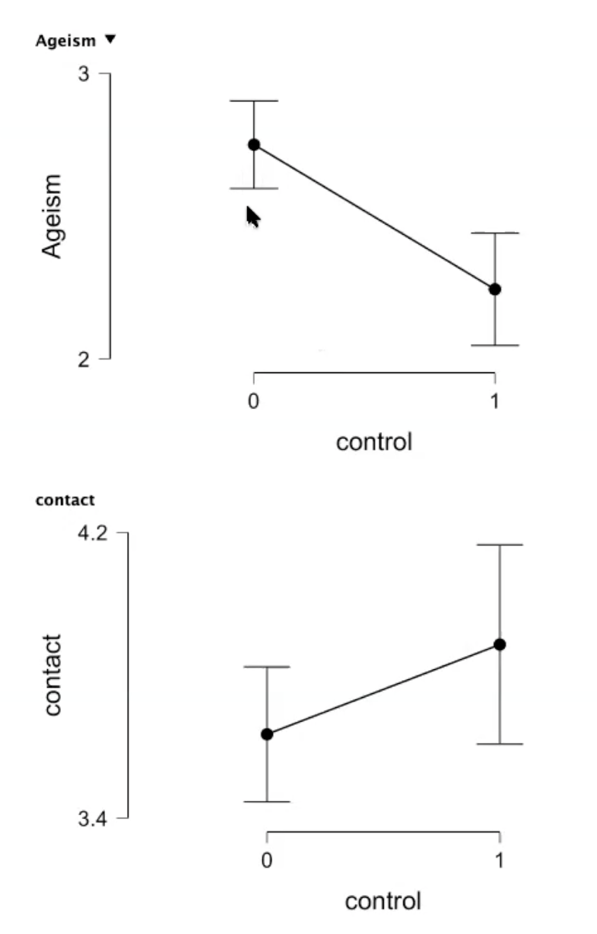

Next, H2 predicted that those middle schoolers who have read WeChat stories will show lower level of (a) perceived threats towards these elders and (b) ageism than those who have not read these stories online. When comparing the manipulation group with the control group, an unexpected result emerged (see Figure 1). Individuals with exposure to various stories on WeChat reported statistically significant higher level of perceived threats (M = 2.26, SD = .71) than those in the control condition (M = 2.23, SD = .87). Moreover, those in the manipulation group reported lower level of intention to contact with elders in the future (M = 3.64, SD = .61) than those in the control condition (M = 3.89, SD = .88). Last but not the least, middle schoolers in these two groups did not differ from each other in terms of ageism. In sum, these findings suggested that stories posted on WeChat did not necessarily alter youths’ perceptions of the older group, not supporting H2.

Figure 1. Difference between control group (= 1) and manipulation group (= 0).

2.4. Discussion

This study recruited 83 Chinese middle schoolers and randomly assigned these youths to read six articles about diverse life stories of elders or a control condition. Everyone was asked to fill in a questionnaire to assess their self-reported level of threats, ageism, and intention to contact with elders. Through data analysis, the first finding is that low intention to contact with elders was associated with higher level of agism and perceived threats towards elders. To test the effectiveness of WeChat stories on changing youths’ perceptions, middle schoolers’ perceptions were compared in different experimental groups. Contrary to the hypothesis, the stories are not associated with more friendliness towards elders, and it did not eliminate the agism from young teens in China. Results also suggested these stories did not necessarily increase youth’s intention to contact with elders. These findings speak to the social contact theory and bear practical implications detailed below.

2.4.1. Revisiting Social Contact Theory in the Context of Chinese Intergenerational Relationship

As this population keep growing in China, the elders are facing increasing challenges, discrimination, and misunderstandings and often seen as social drawbacks in the public eyes. What making the situation worse, it is the byproduct of China’s rapid economic growth that enabled large amounts of new job positions and opportunities in large cities, leaving the older generation in the countryside. After their children had born, the children rarely have the chance to form close-knit relationship with their grandparents, which become the key stone that lead to the generational gap and agism. Having a harmonious and positive intergenerational relationship could benefit the elders in having a better family relationship and a better living environment. According to the research, higher contact leads to lower agism. To form a positive intergenerational relationship, it needs both sides to be responsible, the young children should also be starts to talk to the elders. Thus, this highlights the significance of investigating effectives means to improve relationships between elders and Chinese youths today.

As suggested by the social contact theory, frequent interaction across different social groups increases mutual understandings, alters negative attitudes and prejudice towards each other, and benefits intergroup relationships in the long terms. This study tested this theoretical account in the context of Chinese intergenerational relationships. In consistent with social contact theory, the survey found an important connection that the less the contact young-aged children have with elders the higher age discrimination.

According to the social contact theory, without enough inner-understanding and conversations in-between elders, it will lead to the avoidance and prejudiced stereotype for them. Therefore, according to the results, in the aspect of Chinese teenagers, low intergroup contact with elders is associated with more ageism and perceived threats. Perception of intergroup threat is one of the primary drivers of prejudice toward certain minority groups and immigrants [11][12]. As the division of life gets more specific, the gap between young and elders had widened. During the daytime, after the intensive school or work the younger people prefer staying at home or went out with friends to go to the shopping mall or club. They merely have any opportunity to have close connection with the elders, let along for the patience to have deep conversations to understand each other’s life story. However, according to the survey, the two factors, contact with elders and age discrimination are numerically close-knit.

Based on the founding of the study, there are a few ways to eliminate agism and threats from middle schoolers in China. According to the result, the source of agism and threats are formed because the low frequency of contact with elders. Therefore, to decrease the negativity, it will be necessary to increase the contact between the young and the old. First, teachers in middle school can assign homework, such as spend time with grandparents, to increase the possibility of contact. Furthermore, the parents could lead their kids to be the volunteers in the nursing home, which will also be an effective method to increase the contact frequency for the child.

2.4.2. Unexpected Findings from Reading Elder-Related Stories on WeChat

In this study, there are two reasons the experiments chose to use WeChat stories to alter agism among Chinese young teens. First, after interviews with Chinese older adults, we found the original description or direct quotes from elders relatively less appealing to today’s teens in China. This leads to worry that teens will have no interest in reading these stories. Therefore, in order to draw more attention for these elders’ stories, we decided to narrate the elder’s stories from teen’s perspectives and make it more interesting and relatable for these teens. Secondly, these stories created a diverse and vivid image of Chinese elders, which contradict with the typical impressions that teens usually have towards elders. Hence, we think by showing different aspects of this social group may result in altered attitudes and reduced ageism from the teens.

Unexpectedly, this study did not find the intended effect of reading these diverse stories about elders in China. Rather, teens in the manipulation group exhibited increased ageism and reduced intention to contact with elders in comparison to the control group which did not read these stories on WeChat. One possible explanation is that these teens need longer and more extensive exposure to these stories. After sending out the questionnaires it only took us a week to collect their responds, among this short time period children may not enough time to dig into the details in the elders’ stories. In the present study, this short period of time was not enough for young children to fully understand the underlying meaning of these stories and internalize these inclusive messages as their own attitudes and general perceptions of the elders. Another possibility is that teens did not pay enough attention while reading these stories. As mobile devices are usually self-owned, it is challenging to validate if teens carefully examine messages behind these stories. While manipulation checks were included, most teens in the manipulation group failed to correctly answer those questions. Their responses were still included for analysis as a part of exploratory findings in the current study.

How teens read these stories might also be associated with the way in which individuals were recruited. The WeChat account and survey link were publicized and disseminated in two ways. For the manipulation group, a peer promoted the WeChat account within their social circle and then sent out the survey link to gather individual’s attitudes. It is possible that teens did not carefully follow the instruction as laid out by their peers. In contrast, for the control group, a schoolteacher was contacted to disseminate the survey among their students. As teens in this group evidently have a friendly attitude towards elders, individuals might be subject to social desirability, responding question in accordance with social norms. This also suggests the disseminator as one critical factor that might influence how teens read these stories and its further effects on their attitudes. When the parents and teachers were present and in sponsor of these stories, teens might be more willing to pay close attention to these inclusive messages. Perhaps, more importantly, parents and teachers can assist these youngsters understand the core meaning behind the stories, eliciting a better effect in terms of changing their impressions towards elders.

3. Conclusions

Unfortunately, the stories reading was associated with better attitudes or intimacy towards elders in China. However, we still found correlations between ageism and threats presented by middle schoolers who are not willing to have contact with elders. According to the data, the participants showed higher level of perceived threats towards Chinese elders, if they did not intend to engage in any contact with Chinese elders. Moreover, Chinese middle schoolers who would not like to contact with Chinese elders will show higher level of ageism. Hence, even though the stories are not the key solution for the children to form contact with elders, there are still evidence that proved contact will release agism and perceived threats.

References

[1]. Who.int. 2022. Ageing and health - China. [online] Available at: <https://www.who.int/china/health-topics/ageing>.

[2]. Butler, R. N. (1989). Dispelling ageism: The cross-cutting intervention. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 503(1), 138-147.

[3]. Dong, X., Chen, R., & Simon, M. A. (2014). Elder abuse and dementia: a review of the research and health policy. Health Affairs, 33(4), 642-649..

[4]. Bonnesen, J., & Hummert, M. (2002). Painful Self-Disclosures of Older Adults in Relation to Aging Stereotypes and Perceived Motivations. Journal Of Language And Social Psychology, 21(3), 275-301. doi: 10.1177/0261927x02021003004.

[5]. Ryan, E. B., Giles, H., Bartolucci, G., & Henwood, K. (1986). Psycholinguistic and social psychological components of communication by and with the elderly. Language and Communication, 6, 1– 24.

[6]. Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel, & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

[7]. Harwood, J., Hewstone, M., Paolini, S., & Voci, A. (2005). GP-GC contact and attitudes toward older adults: Moderator and mediator effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 393–406.

[8]. Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of personality and social psychology, 90(5), 751

[9]. Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2000). Does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Recent meta-analytic findings. Reducing prejudice and discrimination, 93, 114..

[10]. Zhang, Y. B., Paik, S., Xing, C., & Harwood, J. (2018). Young adults’ contact experiences and attitudes toward aging: Age salience and intergroup anxiety in South Korea. Asian Journal of Communication, 28(5), 468-489.

[11]. Blumer, H. (1958). Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pacific Sociological Review, 1(1), 3e7.

[12]. Florack, A., Piontkowski, U., Rohmann, A., Balzer, T., & Perzig, S. (2003). Perceived intergroup threat and attitudes of host community members toward immigrant acculturation. The Journal of Social Psychology, 143(5), 633e648.

Cite this article

Liu,L. (2023). Young generation’s attitudes towards aging population. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,2,239-245.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2022), Part I

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Who.int. 2022. Ageing and health - China. [online] Available at: <https://www.who.int/china/health-topics/ageing>.

[2]. Butler, R. N. (1989). Dispelling ageism: The cross-cutting intervention. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 503(1), 138-147.

[3]. Dong, X., Chen, R., & Simon, M. A. (2014). Elder abuse and dementia: a review of the research and health policy. Health Affairs, 33(4), 642-649..

[4]. Bonnesen, J., & Hummert, M. (2002). Painful Self-Disclosures of Older Adults in Relation to Aging Stereotypes and Perceived Motivations. Journal Of Language And Social Psychology, 21(3), 275-301. doi: 10.1177/0261927x02021003004.

[5]. Ryan, E. B., Giles, H., Bartolucci, G., & Henwood, K. (1986). Psycholinguistic and social psychological components of communication by and with the elderly. Language and Communication, 6, 1– 24.

[6]. Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel, & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

[7]. Harwood, J., Hewstone, M., Paolini, S., & Voci, A. (2005). GP-GC contact and attitudes toward older adults: Moderator and mediator effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 393–406.

[8]. Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of personality and social psychology, 90(5), 751

[9]. Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2000). Does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Recent meta-analytic findings. Reducing prejudice and discrimination, 93, 114..

[10]. Zhang, Y. B., Paik, S., Xing, C., & Harwood, J. (2018). Young adults’ contact experiences and attitudes toward aging: Age salience and intergroup anxiety in South Korea. Asian Journal of Communication, 28(5), 468-489.

[11]. Blumer, H. (1958). Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pacific Sociological Review, 1(1), 3e7.

[12]. Florack, A., Piontkowski, U., Rohmann, A., Balzer, T., & Perzig, S. (2003). Perceived intergroup threat and attitudes of host community members toward immigrant acculturation. The Journal of Social Psychology, 143(5), 633e648.