1. Introduction

Nowadays, with the continuous improvement of people’s material living standards, the obesity rate is also increasing. Between 1980 and 2013, the proportion of obese adults in the world rose from 28.8% to 36.9% [1], and obesity has become one of the most important global topics due to some of the negative effects it has brought about.

On the one hand, the damage brought about by obesity to the health of the body is not negligible. Obesity increases the likelihood of diseases such as diabetes and fatty liver, which in severe cases may lead to death and will lead to major healthcare challenges for the country [2]. Obesity, on the other hand, is not in line with the mainstream aesthetics of the entire society, according to the long-standing cultural concept of modern society. Only a few countries in the world consider obesity as beautiful; for example, the traditional culture of the Pacific Islands favors a strong body type [3]. Such a social climate inevitably leads to stigma, discrimination, and negative stereotypes about obesity. It also causes inconvenience and even psychological trauma, such as depression [4]. For example, Agerström and Rooth examined whether people with obesity would be discriminated against in the hiring process [5]. They sampled 153 participants in Sweden and found that hiring managers were more likely to associate obese people with poor performance and were therefore in favor of normal-weight candidates.

However, with the changing of the times, tools such as the Internet, logistics, and transportation networks allow people to have a better and more comprehensive understanding of the wider world, and people are more open-minded than in the past. As a result, people are starting to investigate ways to reduce anti-obesity bias [6].

2. Literature Review

In the dual process theory of social psychology, mental processes are divided into two categories according to whether they operate automatically or in a controlled manner [7-8]. When investigating social attitudes, researchers have also found that they focus on two types of attitudes. One type is explicit attitude, referring to attitudes expressed in a controlled manner. The other type is implicit attitude, meaning that individuals’ introspection does not recognize or accurately identify the influence of past experiences in forming favorable or unfavorable feelings, thoughts, and actions toward social objects [9]. In contrast to explicit attitudes, implicit attitudes are usually unconscious and automatic and cannot be consciously edited.

To study people’s implicit attitudes toward social objects, Greenwald et al. first proposed the Implicit Association Test (IAT) to measure the differential association between target concepts and attributes by comparing people’s reaction times [10]. After that, researchers optimized the algorithm of the original implicit association test through empirical studies to improve its performance [11].

2.1. Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Toward Obesity

Previous studies have been conducted on obesity attitudes using both implicit and explicit methods. Implicit attitudes are usually measured using the implicit association test, while explicit attitudes are measured via self-report questionnaires or surveys. To measure people’s explicit attitudes, researchers have developed a variety of questionnaires. For example, Lewis et al. developed the Anti-Fat Attitudes Test (AFAT) [12]. AFAT included three aspects: first, socially discriminatory beliefs about obese people; second, the perceived physical or romantic unattractiveness of obese people; and third, the attribution of weight control and blame for obesity. The AFAT was shown to have good validity in reliably measuring people’s anti-obesity attitudes. Other than questionnaires, researchers also conducted computer-assisted telephone interviews. For example, Hilbert et al. interviewed 1,000 people in Germany and found negative attitudes toward obesity, with 23.5% of participants having stigmatizing attitudes toward obesity [13].

There are other studies using both implicit and explicit measurements. Flint et al. used the Implicit Association Test and scales to measure the attitudes of 2,380 British adults, and the results showed that British adults had significant negative implicit and explicit attitudes toward obesity [14]. In another study conducted by Vartanian et al., they sampled a group of restrained and unrestrained eaters and found that both groups had negative implicit attitudes toward obesity, but that restrained eaters had more negative explicit attitudes toward obesity, influenced by the internalization of social standards [15]. Besides evidence from Western literature, Phelan et al. found that 4,732 medical students generally had implicit (74%) and explicit (67%) weight bias, and that students from East Asia had stronger explicit bias and negative attitudes toward obesity [16].

2.2. Factors That May Affect Attitudes Toward Obesity

After learning about the general attitudes toward obese people, the researchers further investigated the factors that might influence people’s attitudes toward obesity.

Flint et al. found that obese participants had lower anti-obesity attitudes and fat phobia compared to underweight, normal-weight, and overweight participants; anti-obesity attitudes were stronger in the 18-25 age group than in the 26-50 age group [14]. According to Hilbert et al., predictors of obesity stigma were lower educational levels and older age [13]. In addition, research suggests that adults are more accepting of their obese peers than children, and researchers concluded that adults have more positive attitudes toward obesity [17]. The results of Phelan et al. also showed that both implicit and explicit prejudice against obesity were associated with a lower BMI (an index for obesity) and men, which implies that thinner people and men have stronger negative attitudes toward obesity [16]. The results of a longitudinal study from 2007 to 2020 revealed little change in implicit attitudes toward weight; however, in terms of specific trends, implicit bias decreased by 6% from 2017 to 2022 [18].

From the results of previous research, it can be found that factors such as BMI, age, education level, gender, and chronological changes may influence people’s attitudes toward obesity.

2.3. The Present Study

Previous studies have extensively discussed the factors that may influence people’s attitudes toward obesity. However, some of the findings may have changed with the changing times, and there is a lack of systematic research on implicit attitudes. Based on previous studies, the purpose of this study was to investigate the changes in people’s implicit attitudes toward obesity and the factors influencing them between 2017 and 2021. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Compared to men, women would have more negative implicit attitudes.

Hypothesis 2: The negative implicit attitude towards obesity would have decreased along with the increase in body mass index.

Hypothesis 3: The negative implicit attitude towards obesity would have decreased along with increasing age.

Hypothesis 4: The negative implicit attitude towards obesity would have decreased along with increasing levels of education.

Hypothesis 5: The negative implicit attitude towards obesity would have decreased from the year 2017 to 2021.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

Our data were retrieved from the Project Implicit demonstration website (https://implicit.harvard.edu/) from open data archived at OSF (https://osf.io/a6v7u) [19]. Respondents volunteered to access the site from multiple sources (school assignments, news, etc.) for the experiment, and after obtaining their informed consent, their basic demographic information, such as gender, age, etc., was collected, followed by their implicit attitudes toward obesity [18].

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Implicit Association Test

Greenwald et al. proposed the implicit association test to test individuals’ relative implicit attitudes toward the category under study by measuring the differential association of two target concepts with an attribute [10]. Based on the principle that individuals will respond faster when concept words with high correlations share a response key with attribute words with lower correlations, the masking effect of self-presentation strategies can be well avoided by using this method.

In this experiment, participants were asked to complete a computerized task that tested individuals’ implicit attitudes towards the target concepts of “fat” and “thin” and the attribute words “good” or “bad.”

3.2.2. Materials

The target concepts of this experiment include ten shaded silhouette images of obese individuals, five of each gender, and ten shaded silhouette images of lean individuals, five of each gender. Among the attribute words of this experiment, good words include smiling, appealing, glad, attractive, joyful, delightful, excellent, and terrific; bad words include awful, scorn, horrible, horrific, pain, humiliation, disaster, and tragic.

The experimental material was written as an implicit association test program. First, the instructions appeared, telling the subjects the basic operation and requirements of the experiment and providing the materials of the target concept and attribute words to help the subjects identify and familiarize themselves with the materials in advance to avoid deviations in the experimental results due to cognitive biases.

3.2.3. Experiment Design

Before starting the formal experiment, we collected demographic data about the participants’ birth year and month. Entering the experiment, participants acquired positive and negative words according to the guide words and became familiar with the fat and thin silhouette images.

The experiment required the subject to accurately and quickly determine the category of the word or image in the center of the screen and press the corresponding “E” or “I” key. The procedure was divided into seven parts, including categorizing the target concept and attribute words alone and the joint identification of the target concept and attribute words.

In the first block, the participants were asked to identify and classify the target concept, pressing the “E” for thin people and pressing the “I” for fat people; in the second block, the participants were asked to identify and classify the attribute words, pressing the “E” for bad words, and pressing the “I” for good words; in the third and fourth blocks, the participants were asked to jointly identify and categorize target concepts and attribute words, pressing the “E” for bad words or thin people, pressing the “I” for good words or fat people, the third block is the exercise of the fourth block; in the fifth block, pressing the “E” for fat people, and pressing the “I” for thin people; in the sixth and seventh blocks, the participants were asked to jointly identify and categorize target concepts and attribute words, pressing the “E” for bad words or fat people, pressing the “I” for good words or thin people, the sixth block is the exercise of the seventh block. The experimental procedure is shown in Table 1.

Table1: The weight IAT procedure.

Block | Function | Reaction | |

“E” | “I” | ||

1 | Practice | Thin people | Fat people |

2 | Practice | Bad words | Good words |

3 | Practice | Bad words or Thin people | Good words or Fat people |

4 | Test | Bad words or Thin people | Good words or Fat people |

Table1: (continued).

5 | Practice | Fat people | Thin people |

6 | Practice | Bad words or Fat people | Good words or Thin people |

7 | Test | Bad words or Fat people | Good words or Thin people |

4. Results

4.1. D Scores

We used conventional D scores consistent with previous work [11]. D scores are the difference between the mean response times of the incompatible and compatible blocks. Take the weight IAT as an example: the incompatible block is when participants associate “fat” with good words and “thin” with bad words, while the compatible block is when the participants do the opposite. Positive D scores indicate positive attitudes toward fat people and negative attitudes towards thin people, while negative D scores indicate negative attitudes towards fat people and positive attitudes toward thin people.

4.2. Data Pre-processing

The data was preprocessed to eliminate trials with latencies greater than 10,000 ms and to eliminate data from participants with latencies of less than 300 ms for more than 10% of the trials [11].

Data from subjects without D scores were excluded (511,920). The original sample size was 1,755,949, and 1,244,029 subjects were included after these exclusion criteria. Additionally, 262,772 subjects under the age of 18 were excluded, leaving 981,257 subjects in the final analysis.

We collected information about the height and weight of the participants, and based on this, we calculated the body mass index (BMI) of participants with the formula: weight/height squared.

4.3. Data Processing

To examine whether participants showed implicit weight bias, we conducted a one-sample t-test. We found that implicit D scores were significantly higher than zero, t (981256) = 1171.99, p < .001, 95% CI = [.478, .480], D = .48. These results suggest that participants showed a significant positive attitude towards thin people and a negative attitude toward fat people.

To further examine factors that affect people’s implicit weight attitudes, we conducted a linear regression analysis. To avoid the effect of extreme values, 39,025 participants with BMI below and above three standard deviations were excluded. Five factors were included in the regression model, including participants’ gender, age, education, individual BMI score, and year of completion.

The regression model was significant, ΔR2=.03, F (5,915292) =5465.50, p < .001.

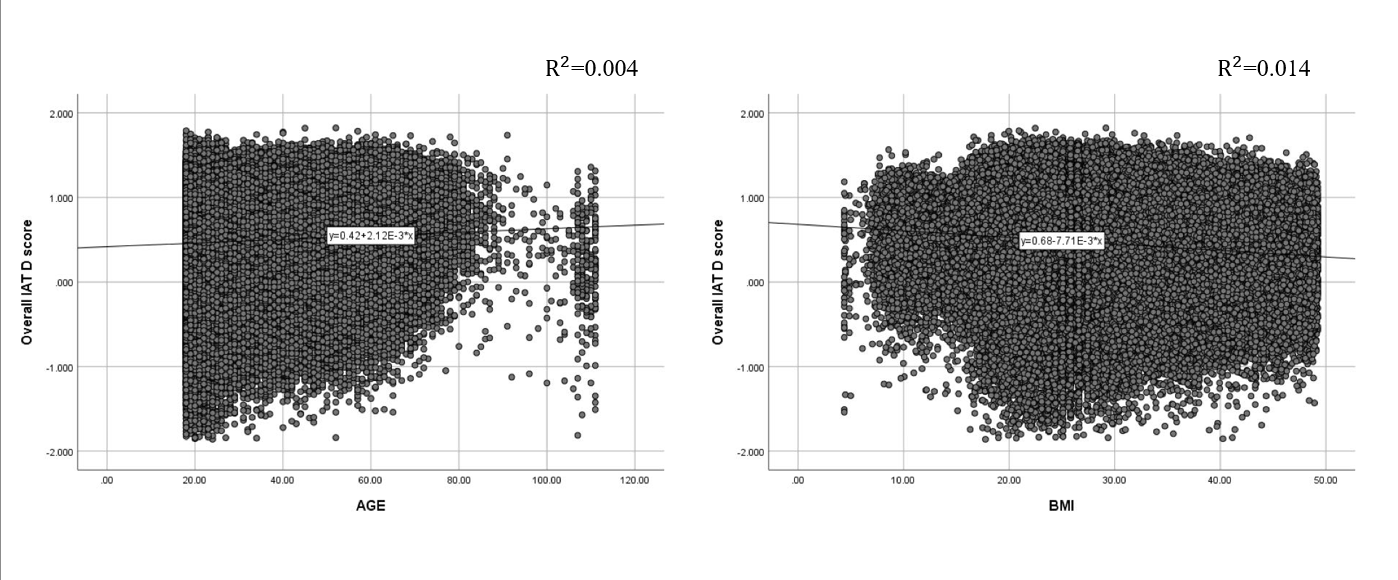

In the regression model, all five factors significantly predicted implicit weight biases. BMI scores contributed 14% of the variance in implicit weight bias, β = -.14, p < .001, part correlation = -.14. The results suggest that as individual BMIs get higher, i.e., as people get fatter, the lower the negative implicit attitudes toward obesity are. Age contributed 12.1% of the variance in implicit weight bias, β = .12, p < .001, part correlation = .10. The results suggest that the older the age, the stronger the negative implicit attitudes toward obesity. Sex contributed 6% of the variance in implicit weight bias, β = -.06, p < .001, part correlation = -.06. The results suggest that females hold a stronger implicit weight bias than males. Education contributed 4% of the variance in implicit weight bias, β = -.04, p < .001, part correlation = -.04. The results suggest that negative implicit attitudes toward obesity decrease as people become more educated. The year of completion contributed 3% of the variance in implicit weight bias, β = -.03, p < .001, part correlation = -.03. The results suggest that as time passes and the era changes, people’s negative attitudes towards obesity become weaker and weaker. See details in Table 2.

BMI and age were shown to be the most significant predictors, contributing 14% and 12.1% of the variance in implicit weight bias, respectively. To further investigate the correlation, we plotted two scatter plots in Figures 1a and 1b. Table 2 provides a summary of the results from the linear regression analysis.

Figure 1: (a) Scatter plot of age and D-score. (b) Scatter plot of BMI scores and D-score.

Table 2: Summary of Linear Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting D Scores.

Variables | B | SE(B) | \( β \) | Part \( r \) |

Sex | -.05 | .001 | -.06 | -.06 |

Age | .004 | <.001 | .12 | .10 |

Education | -.01 | <.001 | -.04 | -.04 |

Year | -.01 | <.001 | -.03 | -.03 |

BMI | -.01 | <.001 | -.14 | -.14 |

5. Discussion

The present study examined the factors that may influence people’s implicit attitudes toward obesity. We used data from the Project Implicit demonstration website, which included the Implicit Association Test, to measure people’s implicit attitudes. We found that BMI, age, gender, education level, and year of test completion all influence results. Below, we discuss each finding in detail.

In terms of gender, contrary to the previous finding [16], women have more negative implicit attitudes toward obesity than men. One possible reason for this result may be due to society’s standards for women’s body image. Researchers studied the cover models of the most popular American fashion magazines in the past and found that the size of fashion models gradually became smaller, and American society paid increasing attention to the image of women as “thin” [20]. In this social context, women implicitly believe that “thinness” is “beauty” and associate “obesity” with a negative image.

We also found that people with a high BMI had a less negative bias toward obesity, while people with a low BMI had stronger implicit negative attitudes toward obesity. These results are consistent with previous findings from Western and Eastern cultures [14,16]. This result can be explained by social identity theory, which suggests that in the assessment process, individuals prefer in-groups and discriminate against out-groups [21]. Participants with higher BMI, as members of the obese group, evaluated the in-group more positively and were reluctant to associate “obesity” with negative attitudes, while participants with lower BMI, as members of the non-obese group, showed a certain degree of discrimination when evaluating the obese group as an out-group.

Previous studies have explored attitudes toward obesity in different age groups. Flint et al. divided participants aged 18 to 65 years into groups based on age, and they found that individuals aged 18 to 25 years had stronger anti-obesity attitudes than other groups [14]. Compared to previous studies, the present study had a broader age range of adult participants, and we found inconsistent results: with increased age, people have stronger implicitly negative attitudes toward obesity. One possible reason for the result could be the fact that, with increased age, people are more susceptible to obesity-related diseases. For example, research by Ford et al. showed that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was 6.7% in the 20-29 age group and increased with age, with a prevalence of 43.5% in the 60-69 age group [22].

Aligning with previous findings [13], a significant finding was that people with higher education held less negative implicit attitudes toward obesity. This finding can be illustrated in terms of personality traits, as Sutin et al. found that people with higher levels of education have higher levels of openness [23]. Therefore, these individuals may have a higher tolerance for obesity.

Consistent with a recent study [18], we found a gradual decrease in implicit bias against obesity between 2017 and 2020. And this trend may be the result of growing concern about the stigmatization of obesity. Multidisciplinary international experts argue that weight is not entirely controlled by individual will but that other factors, such as environment and genetics, can affect it. They believe that discrimination resulting from the stigmatization of obesity can negatively affect obese individuals, so they have issued a joint consensus statement that proposes to eliminate discrimination against obesity [24]. Such a social trend will influence people to reduce the stigma of obesity and, thus, the negative implicit attitudes towards obesity.

5.1. Limitations and Future Research

The data used in this research is a web-based data collection. In the process of data collection, there may be cases where the participants may not respond properly or may not complete their responses, which may affect the accuracy of the data results.

Second, the sample for this study might be a biased sample. The group of people who are willing to go to the website to complete the test may be those who are interested in psychology-related content or those who work in or study psychology, and they may have some basic knowledge to make guesses about the study results to complete a preferred response. In addition, the implicit association test used in this study was in English, which would interfere with the responses of non-native English speakers. All of the above factors may have an impact on the results.

Future research can combine implicit association tests with surveys and interviews to collect people’s attitudes toward obesity, and use appropriate sampling methods to conduct cross-cultural studies, so as to investigate the factors of people’s attitudes toward obesity from the whole society, and thus find appropriate interventions to reduce the stigma of obesity and discrimination against obese people.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the study identified numerous factors that influence people’s implicit attitudes toward obesity, namely: gender, BMI, age, education level, and different years of completion. The results of the linear regression revealed that BMI and age had the strongest degree of influence, followed by gender and education, and finally the year in which people completed the implicit association test. The results have both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, the present study informs the dual process theory by highlighting several key factors affecting implicit social attitudes. Practically, this study can provide relevant and effective suggestions for interventions to reduce stigmatizing attitudes towards obesity, such as educating people’s knowledge about obesity. It is a problem that requires the attention of all sectors of society.

References

[1]. Ng, M., Fleming, T., Robinson, M., Thomson, B., Graetz, N., Margono, C., Mullany, E. C., Biryukov, S., Abbafati, C., Abera, S. F., Abraham, J. P., Abu-Rmeileh, N. M. E., Achoki, T., AlBuhairan, F. S., Alemu, Z. A., Alfonso, R., Ali, M. K., Ali, R., Guzman, N. A., ... Gakidou, E. (2014). Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet, 384(9945), 766-781.

[2]. Sarma, S., Sockalingam, S., & Dash, S. (2021). Obesity as a multisystem disease: Trends in obesity rates and obesity‐related complications. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, 23, 3-16.

[3]. McCabe, M. P., Mavoa, H., Ricciardelli, L. A., Waqa, G., Fotu, K., & Goundar, R. (2011). Sociocultural influences on body image among adolescent boys from Fiji, Tonga, and Australia. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(11), 2708-2722.

[4]. Moazzami, K., Lima, B. B., Sullivan, S., Shah, A., Bremner, J. D., & Vaccarino, V. (2019). Independent and joint association of obesity and metabolic syndrome with depression and inflammation. Health Psychology, 38(7), 586-595. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000764

[5]. Agerström, J., & Rooth, D.-O. (2011). The role of automatic obesity stereotypes in real hiring discrimination. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 790-805.

[6]. O’Brien, K. S., Puhl, R. M., Latner, J. D., Mir, A. S., & Hunter, J. A. (2010). Reducing anti‐fat prejudice in preservice health students: a randomized trial. Obesity, 18(11), 2138-2144.

[7]. Bargh, J. A. (1999). The cognitive monster: The case against the controllability of automatic stereotype effects. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp. 361-382). The Guilford Press.

[8]. Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197-216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197

[9]. Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological review, 102(1), 4-27.

[10]. Gawronski, B., & Creighton, L. A. (2013). Dual process theories. In D. E. Carlston (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of social cognition (pp. 282-312). Oxford University Press.

[11]. Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464-1480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464

[12]. Lewis, R. J., Cash, T. F., & Bubb‐Lewis, C. (1997). Prejudice toward fat people: the development and validation of the antifat attitudes test. Obesity research, 5(4), 297-307.

[13]. Hilbert, A., Rief, W., & Braehler, E. (2008). Stigmatizing attitudes toward obesity in a representative population-based sample. Obesity, 16(7), 1529-1534.

[14]. Flint, S. W., Hudson, J., & Lavallee, D. (2015). UK adults’ implicit and explicit attitudes towards obesity: a cross-sectional study. BMC obesity, 2(1), 1-8.

[15]. Vartanian, L. R., Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (2005). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward fatness and thinness: The role of the internalization of societal standards. Body image, 2(4), 373-381.

[16]. Phelan, S. M., Dovidio, J. F., Puhl, R. M., Burgess, D. J., Nelson, D. B., Yeazel, M. W., Hardeman, R., Perry, S., & Van Ryn, M. (2014). Implicit and explicit weight bias in a national sample of 4,732 medical students: the medical student CHANGES study. Obesity, 22(4), 1201-1208.

[17]. Latner, J. D., Stunkard, A. J., & Wilson, G. T. (2005). Stigmatized students: age, sex, and ethnicity effects in the stigmatization of obesity. Obesity research, 13(7), 1226-1231.

[18]. Charlesworth, T. E., & Banaji, M. R. (2022). Patterns of Implicit and Explicit Attitudes: IV. Change and Stability From 2007 to 2020. Psychological Science, 33(9), 1347-1371.

[19]. Xu, K., Lofaro, N., Nosek, B. A., Greenwald, A. G., Axt, J., & Simon, L. (2022, January 5). Weight IAT 2004-2021. Retrieved from osf.io/iay3x

[20]. Sypeck, M. F., Gray, J. J., & Ahrens, A. H. (2004). No longer just a pretty face: Fashion magazines' depictions of ideal female beauty from 1959 to 1999. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 36(3), 342-347.

[21]. Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of inter-group conflict. In W. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterey: Brooks/Cole.

[22]. Ford, E. S., Giles, W. H., & Dietz, W. H. (2002). Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA, 287(3), 356-359. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.3.356

[23]. Sutin, A. R., Luchetti, M., Stephan, Y., Robins, R. W., & Terracciano, A. (2017). Parental educational attainment and adult offspring personality: An intergenerational life span approach to the origin of adult personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(1), 144-166. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000137

[24]. Rubino, F., Puhl, R. M., Cummings, D. E., Eckel, R. H., Ryan, D. H., Mechanick, J. I., Nadglowski, J., Salas, X. R., Schauer, P. R., Twenefour, D., Apovian, C. M., Aronne, L. J., Batterham, R. L., Berthoud, H., Boza, C., Busetto, L., Dicker, D., Groot, M. D., Eisenberg, D., ... Dixon, J. B. (2020). Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nature medicine, 26(4), 485-97.

Cite this article

Wang,J. (2023). Factors Predicting Implicit Attitudes Toward Obesity: Evidence from Project Implicit (2017-2021). Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,9,127-135.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Ng, M., Fleming, T., Robinson, M., Thomson, B., Graetz, N., Margono, C., Mullany, E. C., Biryukov, S., Abbafati, C., Abera, S. F., Abraham, J. P., Abu-Rmeileh, N. M. E., Achoki, T., AlBuhairan, F. S., Alemu, Z. A., Alfonso, R., Ali, M. K., Ali, R., Guzman, N. A., ... Gakidou, E. (2014). Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet, 384(9945), 766-781.

[2]. Sarma, S., Sockalingam, S., & Dash, S. (2021). Obesity as a multisystem disease: Trends in obesity rates and obesity‐related complications. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, 23, 3-16.

[3]. McCabe, M. P., Mavoa, H., Ricciardelli, L. A., Waqa, G., Fotu, K., & Goundar, R. (2011). Sociocultural influences on body image among adolescent boys from Fiji, Tonga, and Australia. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(11), 2708-2722.

[4]. Moazzami, K., Lima, B. B., Sullivan, S., Shah, A., Bremner, J. D., & Vaccarino, V. (2019). Independent and joint association of obesity and metabolic syndrome with depression and inflammation. Health Psychology, 38(7), 586-595. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000764

[5]. Agerström, J., & Rooth, D.-O. (2011). The role of automatic obesity stereotypes in real hiring discrimination. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 790-805.

[6]. O’Brien, K. S., Puhl, R. M., Latner, J. D., Mir, A. S., & Hunter, J. A. (2010). Reducing anti‐fat prejudice in preservice health students: a randomized trial. Obesity, 18(11), 2138-2144.

[7]. Bargh, J. A. (1999). The cognitive monster: The case against the controllability of automatic stereotype effects. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp. 361-382). The Guilford Press.

[8]. Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197-216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197

[9]. Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological review, 102(1), 4-27.

[10]. Gawronski, B., & Creighton, L. A. (2013). Dual process theories. In D. E. Carlston (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of social cognition (pp. 282-312). Oxford University Press.

[11]. Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464-1480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464

[12]. Lewis, R. J., Cash, T. F., & Bubb‐Lewis, C. (1997). Prejudice toward fat people: the development and validation of the antifat attitudes test. Obesity research, 5(4), 297-307.

[13]. Hilbert, A., Rief, W., & Braehler, E. (2008). Stigmatizing attitudes toward obesity in a representative population-based sample. Obesity, 16(7), 1529-1534.

[14]. Flint, S. W., Hudson, J., & Lavallee, D. (2015). UK adults’ implicit and explicit attitudes towards obesity: a cross-sectional study. BMC obesity, 2(1), 1-8.

[15]. Vartanian, L. R., Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (2005). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward fatness and thinness: The role of the internalization of societal standards. Body image, 2(4), 373-381.

[16]. Phelan, S. M., Dovidio, J. F., Puhl, R. M., Burgess, D. J., Nelson, D. B., Yeazel, M. W., Hardeman, R., Perry, S., & Van Ryn, M. (2014). Implicit and explicit weight bias in a national sample of 4,732 medical students: the medical student CHANGES study. Obesity, 22(4), 1201-1208.

[17]. Latner, J. D., Stunkard, A. J., & Wilson, G. T. (2005). Stigmatized students: age, sex, and ethnicity effects in the stigmatization of obesity. Obesity research, 13(7), 1226-1231.

[18]. Charlesworth, T. E., & Banaji, M. R. (2022). Patterns of Implicit and Explicit Attitudes: IV. Change and Stability From 2007 to 2020. Psychological Science, 33(9), 1347-1371.

[19]. Xu, K., Lofaro, N., Nosek, B. A., Greenwald, A. G., Axt, J., & Simon, L. (2022, January 5). Weight IAT 2004-2021. Retrieved from osf.io/iay3x

[20]. Sypeck, M. F., Gray, J. J., & Ahrens, A. H. (2004). No longer just a pretty face: Fashion magazines' depictions of ideal female beauty from 1959 to 1999. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 36(3), 342-347.

[21]. Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of inter-group conflict. In W. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterey: Brooks/Cole.

[22]. Ford, E. S., Giles, W. H., & Dietz, W. H. (2002). Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA, 287(3), 356-359. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.3.356

[23]. Sutin, A. R., Luchetti, M., Stephan, Y., Robins, R. W., & Terracciano, A. (2017). Parental educational attainment and adult offspring personality: An intergenerational life span approach to the origin of adult personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(1), 144-166. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000137

[24]. Rubino, F., Puhl, R. M., Cummings, D. E., Eckel, R. H., Ryan, D. H., Mechanick, J. I., Nadglowski, J., Salas, X. R., Schauer, P. R., Twenefour, D., Apovian, C. M., Aronne, L. J., Batterham, R. L., Berthoud, H., Boza, C., Busetto, L., Dicker, D., Groot, M. D., Eisenberg, D., ... Dixon, J. B. (2020). Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nature medicine, 26(4), 485-97.