1. Introduction

The Vienna Peace Conference in 1815 established the Kingdom of Parliament Poland on the premise of the three previous partitions of Poland. The Governor of the Kingdom represented the interests of the Russian Empire. Viscount Castlereagh hoped to retain more interests of the Poles, but the final plan still tore apart Poland, which was close to being rebuilt during the Napoleonic period, so it was also called the fourth partition of Poland. The four partitions of Poland resulted in the Poles not being able to control the sovereignty of their own country throughout the nineteenth century, and the Poles were controlled by three empires (more by Prussia and Russia). Nevertheless, compared with the traditional absolutist kingdoms such as Saxony that lost their sovereignty at the same time, the Poles were very prominent in the nineteenth century, from London to Vienna, from Russia to Ottoman, can see the efforts made by the Poles to restore their national sovereignty [1].

Therefore, this article attempts to explain and summarize the formation and development of Polish nationalism from the post-Napoleonic era to the December Uprising of 1863, in order to combine the impact of the fact of being partitioned on the Polish nation (literary and political above). It argues that the division of Poland profoundly shaped early Polish nationalism. The answer to this question will not only help clarify the context of Polish history after 1815, explain the reasons for the successive uprisings in the Kingdom of Poland, but also provide some background explanations for the dislike of the Russian nation by Polish nationalism and the indifference of the German nation.

2. General Threads of Poland over 1815-1864

A Concise History of Poland bluntly called the period from 1815 to 1864 the Challenge partition. Although it is an anthropomorphic expression, the fact is not distant from this. In less than fifty years, Poland broke out three major uprisings (1831/1848/1863) and a lesser uprising (1846). The main task of Polish nationalism during this period was to restore a sovereign Polish kingdom through a combination of violent revolution and diplomatic efforts. Generally speaking, the political situation in Poland in this era was in continuous turmoil, and the source of the turmoil was usually the 10,000 Polish elite who were exiled abroad in 1831. Although the era as a whole has relatively consistent characteristics, it can still be divided into two time periods according to the nature of the uprising and the political nature of the Poland: first, 1815-1831, the era of Congress Poland and second, 1831-1863, the era of underground revolution.

In the first time period, due to the Enlightened tendency of Alexander I, Congress Poland enjoyed a half liberal constitution and a parliament (Sejm), and the rest were partitioned in the fourth division such as the Grand Duchy of Poznan and the Republic of Krakow and even Austrian Galicia also had a certain degree of freedom. During this period, Poland revived several universities (such as Wilno University) and under the auspices of the Tsar, a new University of Warsaw was established. Not only that, thanks to the efforts of Lubecki, Poland signed a trade agreement with Prussia and Russia in 1822, industry and commerce developed rapidly since then. The Lodz Industrial Zone, which will become the center of the textile industry in Poland in the future, was born at this time. The original town of Lodz only had a population of only 2,000 [1].

However, the Decembrist uprising failed in 1825, and the punishment naturally spread to the Poles who had close ties with the Decembrists. The new tsar gradually deprived most of Congress Poland’s original freedom. This finally aroused resistance. The Polish-Russian War broke out in 1831. As a result, Poland failed. The Sejm and constitution were undermined and Poles lost their autonomy; the Grand Duchy of Poznan was annexed by Prussia, and Austria also conspired to formally annex Krakow Republic of Poland [2].

This led to Poland entering a second time period. With the efforts of the exiles, the Polish left-wing “Polish Democratic Association” quickly established contact with the Carbonari, later Young Europe. While the right-wing Czartoryski group’s informal diplomatic relations were established with governments. Under the guidance of “For Our Freedom and Yours”, soon, the left-wing “Polish People’s League” broke out in the revolt against Austria in the Krakow Republic, and then led the Galician Peasant Uprising in 1848, while the right wing Initiated the Poznan uprising of 1848, at the same time the Poles participated in the revolutions in Lombardy, Sicily, Paris, Germany, Vienna, Romania and Hungary as a way to gain diplomatic advantage for the revolutionary movement in their own country. The revolution that swept across Europe in 1848 did not take place in the Polish core and Lithuania because of severe Russian repression. However, the contradictions between Russia and Poland did not disappear. These contradictions finally broke out in 1863 during the period of Tsar Alexander II, who relatively eased the suppression. The left-wing Red Party and the right-wing White Party developed by the revolutionaries in the Kingdom of Poland set off an uprising against Russia. However due to partisan contradictions, Prussian repression and eventually Alexander II’s compromise to liberate Polish serfs, uprisings were also extinguished, after which Polish nationalists at home and abroad entered the era of positivism. Poles seemed no longer focused on bloody revolution, Instead, focus on so-called “organic jobs.” But this transformation of nationalism is irrelevant to the era covered in this article.

3. The Details of Polish Nationalism Throughout 1815-1864

3.1. Nationalism under Limited Freedom in Congress Poland

Before the 1830 revolution, Polish nationalism presented a sense of crisis all the time, and nationalism during this period was alternately affected by three factors. On the one hand, the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was actually divided, and a considerable number of Poles are now living within the borders of Prussia, Austria and Russia. They had different obligations from their compatriots and often have the same obligations as the main nation of the occupying power - which ironically also makes Austria, which was least interested in Polish freedom (obviously, if Poland was free, Hungary, Transylvania and Bohemia also entitled to claim its sovereignty), presented the Poles under the rule gained relatively the most freedom. Because that the system of serfdom in Prussia and Russia during this period is extremely severe. Intellectuals and some of the peasants (if they had chances to go to education system) were also usually forced to learn the language of the host nation [3]. However, the memories of the Constitution of 3 May 1791 and the painful historical memory of being partitioned still exist in these regions—especially in Wielkopolska and Małopolska, which lost their sovereignty only in the third partition. Therefore, the “Germanization” or “Russification” and “de-Polonization” on what they experienced were not carrot and stick, but complete humiliation [4].

On the other hand, a considerable number of old liberal intellectuals in Poland cherish the hard-won Congress Poland and the limited freedom of the Grand Duchy of Poznan, and try to preserve as much power as possible for the kingdom (or themselves) amid uncertainty. In practice, 1815-1830 was the peak of Polish industrial development [5]. This was because of two reasons. First, the Congress Poland was initially set up with high tariff barriers by neighboring countries. The industrialization became the only way to revive the economy. Secondly, due to the abolition of rural personal dependencies, Poland had a large number of landless peasants during this period, which provided sufficient labor and created conditions for the future left-wing Polish revolutionism. However, liberalism also put Poland on the path of free trade, and Potocki’s negotiations with Russia and Prussia in 1821 resulted in low export tariffs for Poland, which further stimulated industrial development. As a result, many liberalists in economic development who benefited were very afraid of the inherent contradiction between Poland and Russia and the revolution that seemed inevitable in the future, and the blow to tariff liberalization and Polish autonomy. Alexander, I saw this, and Nicholas I did not, so when the reckoning with the Decembrists spread to Poland, Nicholas I still tried to conquer the mood in Warsaw with a hard line [3].

The last aspect is the backlash from the Russian and Prussian military authoritarianism of the peoples in the territory of the previous Commonwealth, and, in contradiction to this policy, the Russian liberalism that allowed the liberal constitution to continue in Poland. The consequences of the policy, which naturally have two aspects of influence, one is that Russia’s blind organization of the Poles allowed Poland’s veterans who participated in the Napoleonic Wars to get shelter and weapons, and more importantly, it established a channel for the revival of the Old Commonwealth’s organization (Many underground organizations during this period, such as the “Patriotic Association”, were born in the officer groups), and in 1831, the largest land war in the European continent after the Napoleonic War and before the Crimean War, these Veterans undoubtedly played a more active role than in the relatively poorly organized uprising of 1863. Another link in this influence is the organizational role of newly established universities such as Wilno University on the Polish liberal elites. The generation who grew up in this environment during this period after the partitions of Poland, such as the Three Bards, will write a series of national myths in the history of the Polish nation which became the heart of the period’s struggle.

These three factors made the development of nationalism in the Old Commonwealth territories appeared diffuse and elitist, because the national spirit of Congress Poland, which was still allowed to preserve the old traditions, was mainly reflected in the liberal enlightened aristocrats or industrialists. While in the annexed areas, regional elites and disaffected intellectuals did not have the same channels as Warsaw’s veterans’ organizations to prepare for revolution, and Warsaw’s patriots seemed more willing to cooperate with international elites (such as with Russia’s Decembrists) established contacts rather than mobilizing compatriots who had been converted by other countries. This is why there was no “Sickle Army” in Poland in 1831 as in 1848, because most of the insurgents were officers from Warsaw, and the core of the soldiers enlisted was also the seasoned veteran who is not satisfied with the previous fifteen years.

Likewise, the exile and international nature of Polish nationalism was not very evident during this period. It is true that the Czartoryski group had frequent contacts with the liberals in Paris and the British government during this period, but diplomatic efforts usually took place between Russia and Prussia, not for the independence of Polish sovereignty, but to improve the living conditions of several autonomous regions. This kind of nationalism, which is mild but always fearful of the possibility of being run over by Russia’s “steam roller”, prevented Poland from immediately rebelling in 1825 when Sejm refused to sentence Nicholas I to Poland’s political prisoners. When Potocki, the minister of education for primary and higher education, was dismissed, and when the associations of Wilno University and Warsaw University were disbanded, the resistance did not start immediately as well. Even when the “Patriotic Association” was forbidden once and once again, the Poles also did not seem eager for an armed revolution. However, in the international environment, Russia, which is the European military police, is now triumphantly fighting against freedom. Therefore, compromises applied by Poles did not satisfy the ultra-conservative Nicholas I, but was determined to completely deprive the freedom of the Congress Poland once and for all.

In a way, he was right, because when the Belgian Revolution and the French July Revolution happened, the Polish liberals believed that this would bring international support for their independence, not only in France, they believed. , Britain would also be happy to see Poland tear a hole in European coordination on the conservative European continent to weaken Russia, while Russia also sees this as an excellent opportunity to extinguish the Polish and French revolutions at the same time, once and for all getting rid of its two long-term enemies. Considering these will not only stabilize Russia’s position as the talker in Eastern Europe, but also further expand its influence in Western Europe. Both sides’ calculations were unsuccessful, and the Polish-Russian war was on a scale beyond the imagination of both sides, but regardless of the military details, the characteristics of this general insurrection are worth analyzing, because they will set the stage for the next thirty years of revolution. First of all, in the Polish-Russian War, the liberals did not get the “French support” they expected. France was eager to assure Russia that it was “conservative” and prevent the steam roller from running over Versailles. Also, there were obvious command contradictions. Although the general quality of Polish commanders is better than that of Russia, they often fell into decision-making splits or stagnation due to indecision and contradictions in the political center. Similarly, the political center is clearly divided into two factions. Lelewel advocated the expansion of war, while Czartoryski wanted to preserve power [2]; finally, the elitists could not give the peasants, who accounted for the vast majority of the population, a reason to support the uprising.

These three points became the core of what troubled Polish nationalists from 1831 to 1864. Although the Poles enthusiastically participated in the major revolutions throughout Europe and the world during this period (imagine a nation of only 10,000 people, but in every part of the world’s revolutions have legions of this nation), its own independence movement rarely gets the participation of other nations, and its own independence movement was always divided by the dispute between the hawkish Jacobins and the liberals of the center right. The independence movement developed in this way is often unable to fully mobilize the Poles. This was because the obstruction of Russia and Prussia, Poland cannot abolish all the feudal existence. What is worse, most of the Polish elites never be aware of the importance of mobilizing both urban and rural areas. It was true that Poland had successfully mobilized the rural areas by the Proclamation of Połaniec. With the support of farmers, Kościuszke resisted for two years under the military pressure of the three partitioned countries [3]. But in 1863, when the Red Party finally began to win the support of the peasants, Alexander II announced the liberation of the Polish peasants, which even directly ended the history of Polish armed struggle [1]. Therefore, if we say that the Polish nationalism of 1815-1831 was filled with a sense of crisis in its tranquility, the Polish nationalism of 1831-1864 was plagued by ubiquitous shadows amidst its agitation.

3.2. Oversea Revolutionary Period

The period of 1831-1864 was the most noticeable time of Polish nationalism. However, it is difficult to judge the extent to which this nationalist narrative established by the exile literature was accepted by the Poles in the Commonwealth. But his paper attempts to analyze the characteristics and authenticity of this peculiar non-core nationalism in Poland from the perspectives of nationalists who remained in Poland and Polish nationalists in exile.

The Polish nation from 1831-1864 was clearly divided into two halves, about 10,000 (this number is not the exact final data, different sources claim that different numbers of Poles were forced into exile at this time point, but in any case, this number should not be lower than 7,000 and not higher than about 10,000) Polish elites joined other Polish elites in exile in 1815 and continued to create works about “Polish nationality”, including one of the Three Bards, Adam Mickiewicz [3]. In 1832, he wrote The Books of the Polish People and of the Polish Pilgrimage in which he expressed a point of view that the so-called partition of Poland is the martyrdom of an innocent country, and the significance of this martyrdom is to save the freedom of the whole of Europe [1].

This view is not as far-fetched as it may seem at first glance, as Poland did “save” the French Revolution in 1792 by holding Catherine the Great for two years in an uprising (the subsequent Emperor Paul was not as strong willing to suppress Enlightenment revolutionism). In 1831 the Poles again “saved” the French and Belgian revolutions through a disastrous defeat, which led to Mickiewicz’s own flight to Paris. Among the Poles in exile with such views, “For our freedom and your freedom” is actually more than a slogan used in the United Front. The exiled liberals, so called the sent military officers and even legions to assist all movements related to weakening Russia, hoping that when the Polish independence movement comes, the governments of various countries will also help the Polish nation to weaken Russia; The exiled radicals, such as the Carbonaran Party and the Young European Alliance, fighting for the freedom of nations that have nothing to do with Poland, expecting that when the Polish revolution comes, these organizations will also help the Polish nation to fight. The strategy of the peoples-in-exile did seem to work, and they envisioned a scenario in which, when Russia had been weakened to a certain extent, Poland would regain its sovereignty, along with the tide of European revolution.

Nationalism in the territory of the Old Kingdom has a different development trend. In the eyes of nationalism in exile, the Polish issue may be an international affair, which must be resolved through alliances with other forces. There is another point of view, nationalists did not take a flight tend to mobilize the peasants who make up the vast majority of Poland’s population to start a long war, drag the Russian army into the quagmire and eventually wear it out. The first large-scale manifestation of this characteristic was the uprising of 1846, when for the first time the Poles depended not on officers and nationalist soldiers but on disaffected peasants. In Galicia and Krakow, peasants and workers were mobilized [2]. Subsequently, the Grand Duchy of Poznan in 1848 produced the so-called “scythe army” composed of undertrained peasants. Although the uprising of the extremely poor peasants had economic reasons, they also showed a certain degree of ethnicity agree during this period.

A conflict between these two views broke out in 1863 and to some extent undermined the uprising of the following year. Because the insurgents at the beginning were unable to compete with the regular army in terms of absolute strength, the battlefields were mostly set in rural and remote areas. The Red Shirts and the International Corps fought the battle, but the Whites were reluctant to join the revolution without the support of foreign governments. Three months after the uprising, the White Party was belatedly bringing its own diplomatic support [2]. Not only that, the conservatives and the radicals had strategic conflicts, and Commander Meloslawski himself, as a conservative, also caused It explained the operational tweaks and inconsistencies of the Polish army.

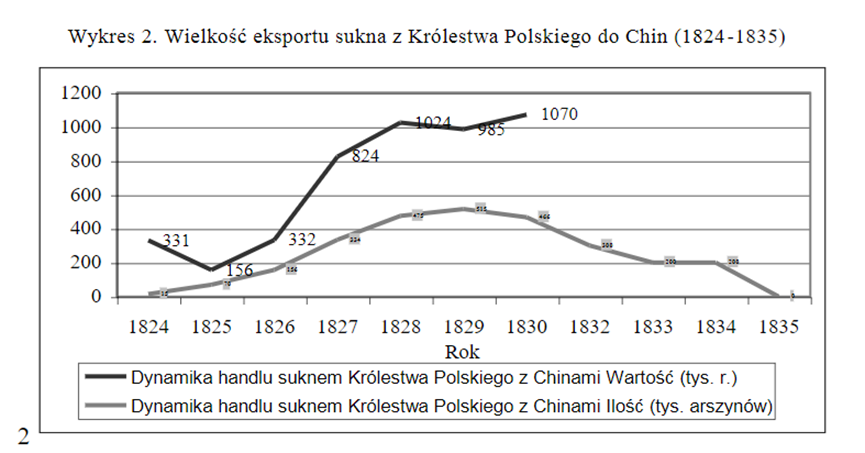

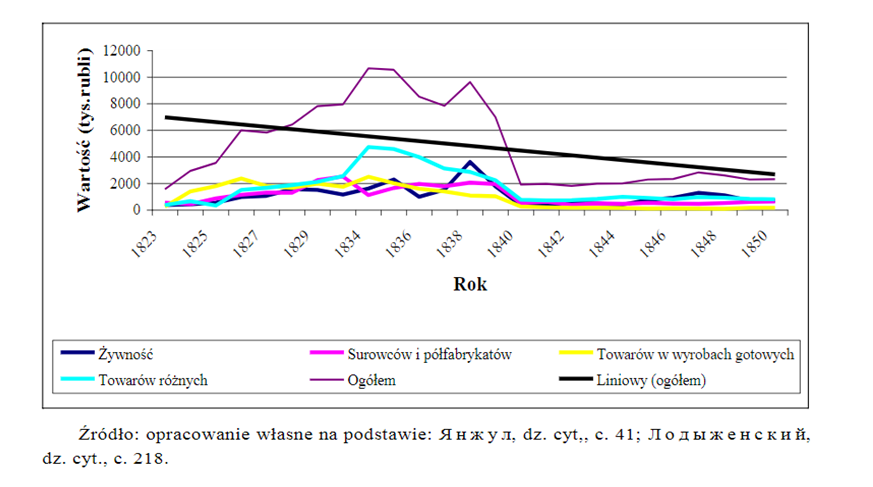

Generally speaking, nationalism achieved considerable development during the period 1831-1864, and the rise of Romantic literature in the 1830s turned Polish culture from paying more attention to specific administrative freedom and economic development to an abstract Polish national identity than in the previous period. This period Poland officially recognized itself as a suffering - not a failed state (nation) [6], especially, after 1831, the situation of the Poles was extremely bad, and the new policy almost canceled the previous period Congress Poland’s all rights of self-government. Tariff barriers were erected again, and the difficult situation of industrial development did not improve until the 1850s (Figure 1 and 2) [5], so it seems very appropriate and timely to seek a sense of identity based on the pain experienced by Poland. The fourth partition of Poland, a recent event fifteen years ago, and the three partitions of Poland that began sixty years ago have become the source of legitimacy of reality and history. The Poles are not only suffering from the partition, and was haunted by this tyrannical shadow from beginning to end.

In terms of tactics, in order to counter the “Germanization” or “Russification” policies, the Poles will not use the “flying school” to emphasize the independence of their language as in the next period [7]. On the contrary, as will be discussed in detail in the next section. In this period, the Poles focused on abstract rights and virtual symbols, which prevented them from continuously dividing and eventually becoming multiple nations like most of the ancient countries that lost their sovereignty during this period. Of course, the annexed so-called “Western gubernia” would eventually develop different national identities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but, despite the existence of the Lithuanian language, Mickiewicz, the poet who was born in Lithuania today, has always written in Polish, and he is firmly loyal to the Polish national identity. This is because what he believed in was not Polish or Lithuanian, but Polish nationalism, or the legacy that nationalists thought they had brought. Therefore, for most of this period, Polish nationalists were obsessed with their historical traditions and developments brought about by the Industrial Revolution. The Szlachtas seemed to be no longer important, and the freedom of the nobility seemed to be a thing of the past. It seems that a unified government has to be established to strengthen the country and avoid repeating the failure of the last century.

However, under the reality of the failure, it has to resort to tradition to ensure the independence of the national spirit, which is itself normal for nationalism process, but the historical traditions of most nations are in fact irrelevant under the wheel of modernity, and the traditions of Poland are actually decentralized aristocratic anarchism and federalism. Therefore, the Poles did not choose Szlachtas or Sarmatism, as its own national myths, instead they chose a new invention that is more in line with the nineteenth century - the constitutional “Constitution of 3 May 1791”. This highly abstract legacy was fitted the tastes of the Polish nationalists of this period very well [6]. And an example like this: A group of students from Wilno for example was punished (some whipped, some sent to Siberia) when one of their number chalked on a wall: “long live the constitution of 1791” [8], will make us see I think that in the future, the Poles will “show off” and provocatively wave the May 3rd Constitution. This is because the failure of the Polish state is not because they are “Infamous” (Staczic). On the contrary, Russia is barbaric, Prussia is tyrannical, and their backwardness So that they can only use violent methods to beat Poland, but cannot assimilate the Poles spiritually. The main task of the Poles is to liberate their noble self from these two domineering neighbors.

The glory of the Constitution of 3 May and the pain of partitioning Poland together constituted the prototype of Polish nationalism in this period of time. Poles living after 1863 may reflect on the inadvisability of armed revolution in this period and the inefficiency of the federal state administration in the 18th century, but they will never doubt the greatness of the Constitution of 3 May, nor the brutal partitions of their two neighboring countries, which continues to this day.

Figure 1: The volume of exports of cloth from the kingdom of Poland to China (1824-1835).

Figure 2: Export dynamics from Russia to Poland (1823-1850).

3.3. Polish Nationalism under a Comparative View

If compare the two time periods 1815-1831 and 1831-1864 vertically, it can be seen that the Polish nation in the first time period behaves surprisingly similar to the “organic work” period after 1864. The big landowners and industrialists tended to soften official Russian attitudes, preserving as much as possible what the Polish elite had achieved. In 1831, Czartorysky even tried to prevent the development of the November Uprising, especially against the possibility of the uprising expanding to the “western gubernia” and the efforts of the radicals to coerce Sejm into formally declaring sovereignty [3]. Not only that, these two periods (1815-1831 and after 1864) were also periods of low tariffs between the Polish region and neighboring countries (after the failure of the uprising in 1864, the Tsar merged Poland into the customs territory of Russia to achieve no tariffs with Russia) [3], industry Development flourished, and because of the presence of newly liberated peasants in both periods, the labor force was plentiful.

But in terms of general sentiment, Polish nationalism was on the rise in the first period of time [1]. Although the main revolutionary leaders were fluky and afraid of rekindling war in Poland, they made very sufficient preparations for a possible war in Poland. The preparations for the development of underground military organizations such as the Patriotic Association, the active diplomatic methods of the main nobles in the Commonwealth, and the formation of a large number of student associations are completely different from the freezing of underground activities during the positivist period.

However, this does not mean that the intensity and breadth of nationalism in the first period has risen to the level after the November uprising. The so-called nationalism before 1831 highly coincided with the old Polish aristocrats who had land power. These people lost a lot of political rights due to partition, so they had a very high sense of identity with the Commonwealth, and they had a very high sense of disgust with the three brutal occupations. This is also the main reason why Austria was able to deal with the nationalist small landowners in Galicia through a peasant uprising in 1848. Nationalism prior to 1831 placed less emphasis on abstract identities – language, common laws and traditions, and not much evidences for that outside of the three universities – Wilno, Warsaw and Jagielonian Universities, there is still much discussion about the constitutional spirit or liberalism of the Constitution of 3 May and the rise of socialism in France and Britain during this period [3]. In the government, the work of Lubetsky and Potocki was transactional, while the modern labor reforms brought about by the landowners of this period were pragmatic. When discussing the Polish nation, Poles focus more on the most recent pain - the fourth partition, and the more distant first three partitions. Polish nationalism in the era of the Congress Poland was a time when it was hit hard by the recent Partition, when Poland was betrayed not only by France in the fourth Partition, but also abandoned by Britain, who they thought would save them (as in WW2). In this period, after the devastation of the Napoleonic Wars (at the cost of hundreds of thousands of Poles’ lives), the Poles had nothing but a limited liberal constitution in a small half-independent kingdom. Given this background, the “timidity” of Czartolotsky and Lubetsky is entirely understandable. The period was dominated by battered grand aristocrats and a new generation of angry Polish elites (such as Mickiewicz and Lelewel) seeking vengeance, and it was this dissonance that ultimately destroyed the November Uprising deeply.

The period of underground revolution after 1831 was more complicated than that of the Congress Poland. The large number of peasants who failed to mobilize in 1831 were seen as a potential force by the radicals of the year, and during this period more and more tenant farmers on the territory of the former Kingdom of Poland showed identification with the Polish nation, despite the view that The “nationalism” that Poland so brilliantly displayed during this period was simply a narrative created by the Polish nation in exile [3], which makes sense, since it seems precocious compared to the traditional nationalist paradigm (where the scope of the language determines the scope of the nation) Polish nationalism seems to place more emphasis on abstract rights, as if the exiles were humanists rather than patriots [9].

The author tends to think that this process actually exists in Poland and is deeply influenced by the world. Undoubtedly, compared with the previous period, the elite played a richer and wider role. This point has been discussed in the second part. However, the indigenous nationalist process was due to two reasons: First, the Germanization policy implemented by Prussia in the former Grand Duchy of Poznań after the failed uprising of 1830; and second, most of the Polish tenant farmers in the western gubernia of Russia were uneducated, so Russia The Russification policy implemented never affected these tenant farmers linguistically, resulting in Germanization being dissatisfied in the Prussian part of Poland and Russification tending to be ineffective [4]. In addition, dissatisfaction with traditional feudal relations also made Polish tenant farmers delusional about Polish national liberation, as the vision of restoring the promise of the Povaniec Declaration and the claims of the exiled left became very tempting under the pressure of Prussia and Russia [2].

Thus, in practice, with the deepening of the Russification and Germanization policy and the underground activities of the Polish Democratic Association in exile, the uprisings of 1848 and 1863 had very different participants, such as the Polish People’s League and the Peasants’ Union. Underground organizations led by intellectuals and made up of craftsmen and peasants replaced the patriotic associations of the previous period made up of officers and nobles, and the uprising in Lower Silesia undoubtedly revived lower-middle-class secret societies such as the Plebes’ League in Poznan. The ensuing Krakow uprising is the best example of the shifting nationalist winds of the previous decade. The “Declaration to the Polish People” produced in this uprising is one of the most radical declarations of the Polish uprising era. Launch a “people’s war” and abolish “class privileges” [2]. As for the uprising in Poznan in 1848 and the uprising that swept across Poland in 1863, it is traditionally considered to be a social revolution that showed the participation of all classes in Poland [1].

If compare Polish nationalism horizontally with other contemporary nationalisms, in the words of historian Stefan Kieniewicz, nationally conscious Poles were those who might make temporary peace with, but could not finally accept the loss of Polish sovereignty [4]. Compared with the nationalist efforts of other peoples in Eastern and Central Europe at the same time, Poland, like Serbia [8], was a multi-ethnic and multi-faith state, united by sovereignty, not the “Language and Poetry” [10]. The Frankfurt Diet contemptuously supported the Prussian army in suppressing the Poznań uprising in 1848 because the Poles did not speak German and thus their rights were not considered by German liberals. On the contrary, the previous uprisings in Poland almost coincided with the original borders. Early Polish nationalism also accepted Lithuanian nobles/Ukrainian landowners/Jewish citizens. This will change at the end of the nineteenth century, but Western Russia after the fourth partition The provinces did not gradually diverge into different nationalities like the nationalities in the Austrian Empire, but insisted on a certain degree of Polish tradition (perhaps more clearly reflected in tenant farmers, this may be due to the implementation of “Russification” in the western gubernia depends on the education system, which was not very popular in the east of Wilno, so the Russification of Polish tenant farmers is virtually non-existent) [4].

However, unlike Serbia, whose historical memory may be rooted in the myths or national legends of the “Kosovo cycle” [8], Polish nationalism has specific symbols, such as the four partitions, May 3 Constitution and Sejm, etc. If one looks at the efforts to defend these figurative symbols, Polish nationalist beliefs at this time appear to be indestructible. Because Serbia’s armed uprising was relatively successful, the Serbs received more positive feedback, unlike the Poles, who never won. However, the failure of the armed uprising did not substantially hit the historical memory of nationalism. They were in part reinforced by the tsar’s ruthless repression.

4. Conclusion

Generally speaking, Poland after being partitioned developed a large-scale nationalism very early because of its historical origins. Compared with the international nature of the Greek uprising, the Polish uprising was completely dominated by the Poles, although the Poles were from beginning to end tried to expand its nationalist movement into international affairs, but from the results, apart from the abstract international cultural identity, there was almost no specific international assistance. Compared with other national independence movements involving political conflicts among many imperialist countries, Poland’s national independence movement was overwhelmingly suppressed by three neighboring countries.

The period from 1815 to 1864 was a stage in which the underpinnings of Polish nationalism were formed, and despite bitter failures, the Polish elites analyzed the situation more utilitarianly. After these fifty years of failure ended, the Poles almost completely abandoned all the idealisms of the past - aristocratic democracy and constitutionalism naturally included them. In the future, the success of right-wing dictators like Pisudski who did not conform to the traditional political taste of Poles also owed the credit to this kind of pragmatism. In terms of international affairs, for the Poles (even the Baltics and Ukrainians), the Orthodox Slavic culture and the Protestant Germanic culture have become natural enemies and have become part of historical memory, which will continue to this day.

References

[1]. Zamoyski, Adam. Poland: A History. Hippocrene Books, 204-275. New York, 2012.

[2]. Liu, Zuxi. General History of Poland. The Commercial Press, 195-284. Beijing, 2006.

[3]. Lukowski, Jerezy and Hubert Zawadzki. A Concise History of POLAND. Cambridge University Press, 173-233. Cambridge, 2006.

[4]. Kamusella, Tomasz. “Germanization, Polonization and Russification in the Partitioned Lands of Poland-Lithuania: Myths and Reality”, Nationalities Papers, vol. 41, no.5(2013): 815-838.

[5]. Rozumowska-Gapeeva, Tatiana. “Economic Relationships Between Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Poland in 1815-1850”, Roczniki Wydziału Nauk Prawnych i Ekonomicznych KUL 2, no 2(2006): 261-279.

[6]. Hillar, Marian. “The Polish Constitution Of May 3, 1791: Myth and Reality.” The Polish Review 37, no. 2 (1992): 185–207.

[7]. Evans, Richard J. The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815-1914. Viking, New York, 2016.

[8]. John Connelly. Annual Kolakowski Lecture - What makes Poland special: Polish Nationalism in Comparative Context (15 February 2016). St. Antony’s College, Nissan Lecture Theatre, 62 Woodstock Rd, Oxford OX2 6JF.

[9]. Dean, Jonathan, “Interpretations of Revolution in Partitioned Poland”. Research Papers, 1(2016). https://scholarworks.moreheadstate.edu/msu_honors_research/1.

[10]. Johann Gottfried Herder. Treatise on the Origin of Language. Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2014, 1-50.

Cite this article

Wang,Y. (2023). The Development of Polish Nationalism in the Period 1815-1864 after the Fourth Partition of Poland. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,10,324-333.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zamoyski, Adam. Poland: A History. Hippocrene Books, 204-275. New York, 2012.

[2]. Liu, Zuxi. General History of Poland. The Commercial Press, 195-284. Beijing, 2006.

[3]. Lukowski, Jerezy and Hubert Zawadzki. A Concise History of POLAND. Cambridge University Press, 173-233. Cambridge, 2006.

[4]. Kamusella, Tomasz. “Germanization, Polonization and Russification in the Partitioned Lands of Poland-Lithuania: Myths and Reality”, Nationalities Papers, vol. 41, no.5(2013): 815-838.

[5]. Rozumowska-Gapeeva, Tatiana. “Economic Relationships Between Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Poland in 1815-1850”, Roczniki Wydziału Nauk Prawnych i Ekonomicznych KUL 2, no 2(2006): 261-279.

[6]. Hillar, Marian. “The Polish Constitution Of May 3, 1791: Myth and Reality.” The Polish Review 37, no. 2 (1992): 185–207.

[7]. Evans, Richard J. The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815-1914. Viking, New York, 2016.

[8]. John Connelly. Annual Kolakowski Lecture - What makes Poland special: Polish Nationalism in Comparative Context (15 February 2016). St. Antony’s College, Nissan Lecture Theatre, 62 Woodstock Rd, Oxford OX2 6JF.

[9]. Dean, Jonathan, “Interpretations of Revolution in Partitioned Poland”. Research Papers, 1(2016). https://scholarworks.moreheadstate.edu/msu_honors_research/1.

[10]. Johann Gottfried Herder. Treatise on the Origin of Language. Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2014, 1-50.