1. Introduction

People from different countries exhibit distinct national characteristics and behavioral patterns influenced by various macro-level factors such as politics, economics, and culture. Among these, the impact of education is particularly significant and crucial, as it plays a fundamental role in shaping individuals, influencing national identities, and transmitting cultural values. Notably, the variance between American and Japanese cultures in terms of individualism and collectivism, as elucidated in Hofstede’s concepts [1], is striking. This research aims to expound upon the profound effects of education on these cultural dimensions based on previous studies.

Ruobai proposed that collectivism in Japan can be reflected in various activities in elementary and junior high schools, such as school trips [2]. Qian believed that American education focuses more on cultivating personal interest in learning, which reflects the core values of American individualism [3]. Through the comparison of American and Japanese textbooks, Lanham mentioned that Japan emphasizes perseverance and self-discipline to achieve success, while the United States attaches great importance to reducing the pressure on children and stimulating their own innovation in order not to stifle children's self-confidence [4].

However, there are still some scholars who hold the opposite opinion. For example, Befu argued that due to the large regional and cultural differences in Japan, it is difficult to achieve collectivism in the full sense of the word, and this is reflected in discrimination among students in schools [5]. Collectivism is also the name given by the European and American world in order to oppose themselves. Wang believed that the United States is a melting pot of races, and in order to ensure its political stability, it is bound to need the support of collectivism, which is reflected in patriotic expression [6]. In education, the school organizes students to sing the national anthem together.

The current research gap lies in the need to comprehend the influence of education on individualism and collectivism and recognize that cultural dimensions are not static but evolve over time. This paper seeks to bridge this gap by employing the Literature research method and comparative research method, contrasting the differences in American and Japanese school education to demonstrate how Japan's education system embodies collectivism, and similarly, the United States embodies individualism.

The primary objective of this paper is to unravel the underlying factors contributing to differences in personality across nations, thus reducing biases and preconceptions. If people can recognize the profound impact of education on cultural dimensions, they can not only better understand individuals from different countries but also foster improved collaboration between nations.

2. Hofstede’s Theory of Individualism and Collectivism

Hofstede brought up a framework theory of cross-cultural communication [1] based on 117000 questionnaires from 40 countries, covering people from all walks of life, from workers to doctors and top managers, and people of different income groups. This paper focuses on the comparison of collectivism and individualism in this concept, with the most representative examples of the United States and Japan.

The United States is an individualistic society, while Japan is a collectivist society [7]. The United States emphasizes individual success both in schools and companies and focuses on rewarding individuals for their outstanding results. On the contrary, Japan places greater emphasis on stimulating individuals' sense of responsibility for collective organization.

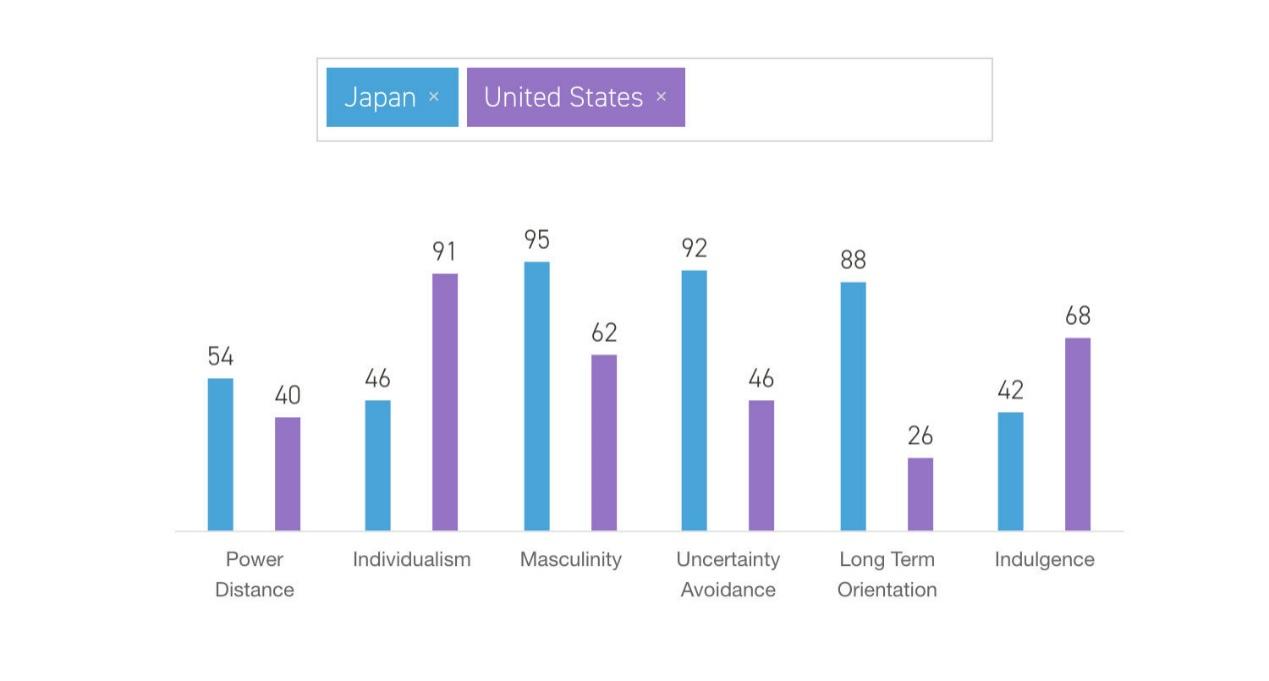

Figure 1: Individualism and Collectivism of America and Japan [8]

Figure 1 presents the comparison of individualism and collectivism between America and Japan. It can be found that the United States is more independent than Japan. The United States has a clear individualistic character, while Japan shows more collectivist characteristics than the United States.

3. Japanese and American Education Models

3.1. Japanese Education Model

Someone described the Japanese as follows: “The Japanese are like bees” [9]. Japanese people are better able to play their strengths in a group than individuals. They know how to work together in a group to make the collective more powerful.

Japanese collectivism is reflected in elementary education through different types of activities. From the very beginning of elementary school, Japan teaches students to observe collective order and organize students to carry out group activities, such as student council, in-class selection, and school-level selection. One of the most representative activities is a school trip to Japan. The school organizes group trips of about a week in groups. Students act together with their classmates, feel happy together, and overcome difficulties together.

Mathematics education in Japan also embodies collectivism. Japan's mathematics education is stronger than that of many countries, and it is inseparable from the influence of Japanese collectivism on mathematics education. Teachers treat all students equally and do not ignore those with poor grades. Excellent students in the Japanese class will help poor students, and poor students will also work on their own, or take the initiative to go to cram school to improve their grades and meet the standards of the class.

In response to this kind of collectivist education, Japan also has excellent supporting facilities. There are many cram schools in Japan, which are called juku in Japa. Juku is a place dedicated to improving students' academic performance. Juku is classified in detail, where students can get remedial for almost all courses.

Collectivist education in Japanese primary and secondary schools, inheriting the Japanese cultural tradition, has been a great success as an extension of family education [2]. Education is influenced by culture and plays an important role in cultural dissemination. Japanese education also implicitly conveys Japanese ideological values, and collectivism is one of them. These ideas are also internalized into students' own character in the process of education. When students grow up, integrate into society, and form their own families, these ideas will also affect their children and continue for generations to come.

3.2. American Education Model

From the perspective of the design of the American education system, its overall goal is not to pursue the short-term effect of individual development, but to pay attention to the consideration of individual long-term development. That means that the cultivation of independence, thinking, critical and creativity that have an important impact on the future development of the individual is the overall goal of individual development. Let children rely on their own strength from an early age, develop multi-faceted interests, cultivate practical life skills, and form a function of independent development and expression of personality.

Americans believe that the teaching process should be a process that stimulates students' interest in learning and guides individual students to continue to explore [3]. Teachers in American schools encourage students to take the initiative to acquire knowledge and actively express their opinions. Schools in the United States expect students to have their own thinking and research skills. Because of that, American schools have a relaxed management system as well as lots of events, in order to create a free environment that helps them to explore their interests and express themselves confidently.

The core value of the United States is individualism, so its educational value orientation is individual [10]. American schools believe that the fundamental purpose of education is to make people’s personalities and instincts develop naturally. People should be born free, not bound by old things, and the world is led by new people with ideas and vitality.

4. A Comparison Between the United States and Japan

4.1. Social Characteristics of the United States and Japan

Japanese society shows many of the characteristics of a collectivistic society. Such as emphasizing harmony and hierarchy within the group above the expression of individual opinions. Moreover, the Japanese have a strong sense of shame. There is a clear hierarchy, and they put the collective good first and also be willing to give up personal interests for it.

The premise of America is “liberty and justice for all”. This is also reflected in the clear emphasis on equal rights in all aspects of American society and government. In the organization of the United States, the superiors are approachable. Both managers and employees can communicate directly, and this exchange is usually informal, which has a strong participation. In this society, people are expected to take care of only themselves and their immediate relatives.

4.2. Textbooks for the United States and Japan

Individualism and collectivism can be found in storylines in American and Japanese textbooks. Through Lanham’s survey of Japanese textbooks [4] and the comparison of American textbooks, Japanese textbooks focus on the hardships of someone's path to success. For example, the textbooks of the fifth and sixth grades usually show some stories of great scientists who have experienced adversity, ridicule, or weakness and finally achieved success. Japanese textbooks emphasize that success must experience setbacks and requires perseverance and hard work while in order to promote students' self-confidence and stimulate students' creativity, American textbooks will avoid emphasizing this point. This phenomenon illustrates that the American educational system emphasizes self-confidence, while the Japanese education system focuses more on hard work and self-discipline.

4.3. School Regulations

Through school management in the United States and Japan, the embodiment of individualism and collectivism can also be seen [11].

Regarding ability grouping, there is more ability grouping in the US than in Japan. For after school, many US students work after school while most Japanese students go to cram school (juku) after school. In terms of the daily schedule, American class is eight hours a day but fewer days per year and there are no classes on Saturday and Sunday. However, in Japan, Japanese class is Six hours a day but more days per year. Many schools still meet on Saturday despite a movement to phase this out starting in 1992. Regarding dress, in American schools, student uniforms are not common and around 20 percent of public schools require uniforms while in Japan, all public high school students must wear a uniform. Everyone must remove their shoes at the entrance and change into indoor shoes.

American students have abundant after-school activities, and Japanese students focus on improving their grades after class. The United States does not have too strict standardized assessments, focusing on comprehensive ability. Japan pays attention to standardized tests and so on.

Firstly, for the examination, in America, there is no entrance exam for high school. There are more short essay questions than in Japan. While Japan has an entrance examination and also has a more complicated form of exam such as multiple choice. Secondly, regarding funding, US schools are mostly financed by property taxes, while In Japan national government takes responsibility for one -third of the school funding. Thirdly, regarding the outcome, the US scores lower on most international math and science tests compared to Japan. In Japan, there is a perception that the US does better in critical thinking than Japan. Japanese students have consistently ranked first in mathematics literacy and second in science literacy.

The difference in the role of the teacher and student between America and Japan is also distinct. In America, the teacher is more of a facilitator. Teachers use a more transactional teaching style and encourage discussion. While in Japan, the teacher is more of a director. Teachers see their roles as that of a transmitter of knowledge and students should focus on receiving that knowledge and use more lectures and less discussion. In America, students are expected to be more active. Classroom participation is important. The relationship between teacher and student is more informal. However, in Japan, Students are expected to be more passive. The relationship between students and teachers is more formal.

5. Discussion

5.1. Japan

Japan is certainly a collectivist society, however, it is not complete. There are a lot of misconceptions about it.

Japan is not a large family society, so collectivism is less characteristic than in South Korea and China, and they are hostile or indifferent to members of groups outside the family. According to Befu [5] Japan is not only geographically separated (e.g., Hokkaido and Okinawa), but also has its own different cultures and languages (e.g., Ainu and Ryukyu/Okinawan), which create great differences and confusion between the people of each region. since Japanese is their second language, there is a tendency for Japanese regions to isolate each other. In terms of education, it will be reflected in the discrimination of the campus. Befu also mentioned that Western countries have a misunderstanding. For example, the United States considers Japan to be the opposite of itself, so Japan is considered collectivist.

Individualism was generally regarded neutrally in Japan [12]. This neutral attitude also suggests that individualism is a relatively common phenomenon in Japanese society.

In education, individualism is reflected in a special tuition institution in Japan called Kumo. Although it is a tuition institution, it is not a traditional model of teachers giving a lecture while students listen below. Kumon’s classroom doesn't have a blackboard, each student has their own one-on-one teacher. Kumon education aims to stimulate students' ability to explore themselves, solve problems, and find answers on their own under the guidance of teachers. This teaching mode is conducive to stimulating children's ability to innovate, create , and think in multiple dimensions, and satisfying students’ self-confidence and satisfaction in learning. This educational model and philosophy are also widely popular in the United States, which advocates freedom and independent thinking.

5.2. America

Diane M. Hoffman argued that it is often misleading to simply emphasize the group orientation and individual orientation of the United States and Japan [13]. The totality of individual and group orientations needs to be judged on the basis of people's basic assumptions about themselves. People also tend to confuse the distinction between individuality and individualism, especially in the United States, a society where individuality is fully developed. In addition, the United States is an individual-centered society. It seems that Americans seem particularly egoistic, without a sense of collectivity. Wang thought that, because it is a new country composed mainly of immigrants, in order to strengthen the sense of national identity, the United States attaches great importance to patriotism and national identity education [6].

6. Conclusion

This paper aims to contrast the educational models of Americans and Japanese. First of all, this paper shows the characteristics of Japanese collectivism and American individualism respectively. In Japan, collectivism is epitomized in some activities which need the whole class to do together. In America, individualism is epitomized in core values, which encourages the innovation and confidence of American students.

The comparison between the United States and Japan is from three aspects which are social characteristics, textbooks, and school systems. It can be found that education has a profound impact on individualism and collectivism in the cultural dimension. Japan’s educational system perfects collectivism by emphasizing discipline in regulation and ideology, while the America educational system ensures individualism by highlighting freedom in both direct and indirect ways.

Generally speaking, the American educational model tends to individualism while the educational model of Japan tends to collectivism. Nevertheless, there are also some opposite situations that can be found in areas isolation of in Japan and patriotism in America.

In conclusion, this paper illustrates the difference between American educational models and Japanese educational models and shows their values toward individualism or collectivism. However, this paper lacks actual investigation and needs to be adjusted in future research.

References

[1]. Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions form James Madison University hofstede-individualism. pdf (jmu.edu).

[2]. Ruo Bai, On the Cultivation of the Spirit of Collectivism in Japanese Primary and Secondary Schools, Studies in Foreign Studies, 1997, No. 2, pp. 11.

[3]. Qian Haijuan, Analysis of Personalized Education in the United States. Journal of Inner Mongolia Normal University: Education Science Edition, 2005, No. 9, pp. 76.

[4]. Betty B. Lanham, Ethics and Moral Precepts Taught in School of Japan and the United States. Ethos, 1979, Vol.7, No.1, p9.

[5]. harumi befu, Concepts of Japan, Japanese culture and the Japanese, Cambridge Companion to Modern Japanese Culture, April 2009.

[6]. Wang Yanzhong, Characteristics and Paradox of American Culture, Journal of Shanxi Normal University (Social Science Edition), 2021, Vol. 48, No. 4, pp. 1-13.

[7]. He Mingxia, The Research on Cultural Difference from the Perspective of Cultural Dimension Theory, [D], Heilongjiang University, 2011, pp. 9.

[8]. Individualism and Collectivism of America and Japan, https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool

[9]. Wang Liang, Collectivism in Japanese School Education: Centered on Primary Education. Northern Literature (Second Half), 2012, No. 8, pp. 162.

[10]. Liu Qingqin, A Discussion of Educational Values under the Influence of American Individualist Culture. Journal of Tianjin Academy of Education Sciences, 2011, No. 4, pp. p49.

[11]. The difference of school regulations between America and Japan, https://foxhugh.com/multicultural/american-versus-japanese-high-school/

[12]. How do Japanese Perceive Individualism? Examination of the Meaning of Individualism Japan, Ogihara, Y.a, Uchida, Y.b, Kusumi, T.a; PSYCHOLOGIA, 2014, Vol. 57, No.3, pp, 221.

[13]. Individualism and Individuality in American and Japanese Early Education: A Review and Critique, Hoffman, Diane M., American Journal of Education;2000, Vol.108, No.4, pp. 300.

Cite this article

Hu,W. (2024). Comparative Analysis of American and Japanese Educational Models. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,36,176-181.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions form James Madison University hofstede-individualism. pdf (jmu.edu).

[2]. Ruo Bai, On the Cultivation of the Spirit of Collectivism in Japanese Primary and Secondary Schools, Studies in Foreign Studies, 1997, No. 2, pp. 11.

[3]. Qian Haijuan, Analysis of Personalized Education in the United States. Journal of Inner Mongolia Normal University: Education Science Edition, 2005, No. 9, pp. 76.

[4]. Betty B. Lanham, Ethics and Moral Precepts Taught in School of Japan and the United States. Ethos, 1979, Vol.7, No.1, p9.

[5]. harumi befu, Concepts of Japan, Japanese culture and the Japanese, Cambridge Companion to Modern Japanese Culture, April 2009.

[6]. Wang Yanzhong, Characteristics and Paradox of American Culture, Journal of Shanxi Normal University (Social Science Edition), 2021, Vol. 48, No. 4, pp. 1-13.

[7]. He Mingxia, The Research on Cultural Difference from the Perspective of Cultural Dimension Theory, [D], Heilongjiang University, 2011, pp. 9.

[8]. Individualism and Collectivism of America and Japan, https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool

[9]. Wang Liang, Collectivism in Japanese School Education: Centered on Primary Education. Northern Literature (Second Half), 2012, No. 8, pp. 162.

[10]. Liu Qingqin, A Discussion of Educational Values under the Influence of American Individualist Culture. Journal of Tianjin Academy of Education Sciences, 2011, No. 4, pp. p49.

[11]. The difference of school regulations between America and Japan, https://foxhugh.com/multicultural/american-versus-japanese-high-school/

[12]. How do Japanese Perceive Individualism? Examination of the Meaning of Individualism Japan, Ogihara, Y.a, Uchida, Y.b, Kusumi, T.a; PSYCHOLOGIA, 2014, Vol. 57, No.3, pp, 221.

[13]. Individualism and Individuality in American and Japanese Early Education: A Review and Critique, Hoffman, Diane M., American Journal of Education;2000, Vol.108, No.4, pp. 300.