1. Introduction

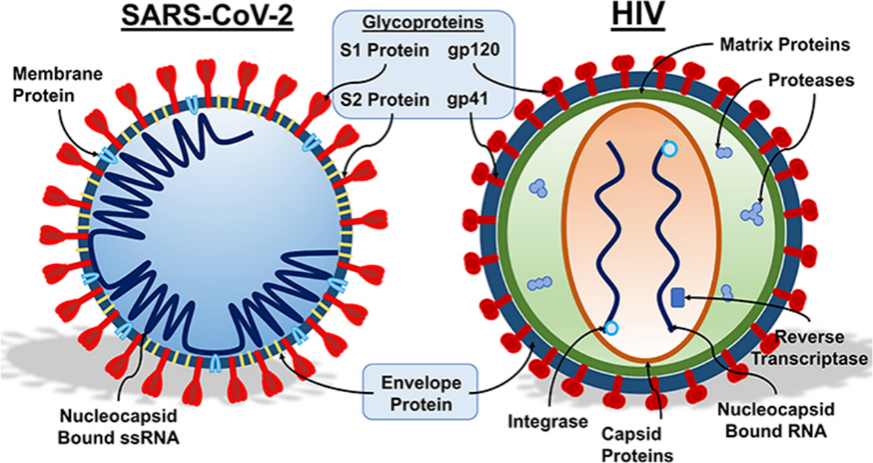

The emergence, outbreak, and frequent occurrence of coronaviruses pose severe threats to global public health security and the health of the livestock industry. Although vaccines developed against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have been widely used, the administration of over 6.6 billion doses has failed to halt the current global pandemic of SARS-CoV-2. A variety of newly emerging viral strains with immune evasion capabilities have gradually become the dominant strains [1, 2]. In the long-standing battle between humans and viruses, the immune system functions like a sophisticated defense network: antibodies recognize antigens on the viral surface, similar to sentinels identifying the uniform markers of invaders. However, as show as Figure 1, viruses have evolved a cunning disguise strategy: they "clothe" their key antigenic proteins with dense glycan coats, rendering immune weapons ineffective. This phenomenon, known as Antigen Glycosylation, has become a core battlefield in modern virology and immunotherapy [3].

Glycosylation modification is a post-translational protein modification that plays a crucial role in processes such as maintaining host protein stability, enhancing signal transduction, regulating coronavirus infection, cross-species transmission, and immune evasion [4, 5]. When viruses replicate within host cells, they hijack the cell's glycosylation machinery to attach glycans to specific sites on viral proteins (asparagine residue-linked N-glycosylation/serine or threonine residue-linked O-glycosylation). These glycans are not random decorations but form a dynamic Glycan Shield [6, 7]. For instance, the spike (S) protein of SARS-CoV-2 possesses 66 potential glycosylation sites, with glycans covering over 40% of its surface area; glycans at the N234 and N709 sites directly enwrap the ACE2 Receptor-Binding Domain (RBD) (Figure 1) [8]. The glycans on the Envelope (Env) protein of HIV account for up to 50% of its total mass—far exceeding the 5-10% ratio in human proteins—and mask more than 90% of neutralizing epitopes (Figure 1) [9, 10]. These glycans form a dense physical barrier (the Glycan Shield) while mimicking the molecular signals of the human body, allowing viruses to "wear" a "molecular camouflage suit" and successfully evade immune surveillance [11].

The role of glycosylation in immune evasion was first discovered during the 1968 Hong Kong influenza pandemic: the acquisition of a new N165 glycosylation site on the viral Hemagglutinin (HA) protein enabled the virus to escape antibodies induced by the vaccines available at that time. This finding explained why influenza vaccines need annual updates—viruses achieve "antigenic drift" by adding or removing glycosylation sites [12]. Since the 21st century, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and SARS-CoV-2 have taken the glycan shield strategy to extremes: the number of glycosylation sites on the Env protein of HIV is 5-10 times that of human proteins, making it a major cause of vaccine development failures [13]; the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, by acquiring a new N371 glycosylation site, reduced the efficacy of the original vaccines [14].

Therefore, studying the glycosylation modification of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein is of great significance for elucidating the pathogenic mechanism and supporting the development of anti-coronavirus drugs and vaccine optimization [15, 16]. This review will focus on the concept of SARS-CoV-2 S protein glycosylation, the significance of glycosylation, and the mechanisms of immune evasion.

2. Mechanisms by which glycosylation assists viral immune evasion

Glycosylation, as a key post-translational modification, is widely involved in the process of viral immune evasion [17]. Its mechanisms primarily include the physical shielding effect (Glycan Shield) and the mimicry of host "self" signals (molecular mimicry), aiding viruses in evading immune recognition and clearance through both spatial occlusion and immune deception [18].

2.1. Physical shielding effect (glycan shield)

Physical shielding is one of the core strategies of viral glycosylation-mediated evasion. Viruses add high-density glycans to their antigen surfaces, forming a dynamic physical barrier that occludes critical antigenic epitopes and receptor-binding domains [19]. Taking the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) as an example, its spike (S) protein possesses over 66 N-glycosylation sites, with glycans covering more than 40% of its surface area. Studies show that the glycan at the N165 site can insert into the binding interface between the Receptor-Binding Domain (RBD) and the neutralizing antibody REGN10987, significantly increasing the binding free energy and reducing antibody affinity [20]. After the Omicron variant acquired new glycosylation at the S371L/S373P sites, the half-maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC₅₀) of the neutralizing antibody S309 significantly increased, demonstrating the dynamic evolutionary nature of glycosylation in viral variation [24]. A similar mechanism exists in HIV-1; its Env trimer possesses 88-92 glycosylation sites, with a glycan coverage rate as high as 52% [21]. The V1V2 region forms a "glycan island" structure, blocking the recognition of broadly neutralizing antibodies (such as PGT121) within a 1.5-nanometer range around the CD4 binding site [22]. Experiments confirm that deleting 5 key glycosylation sites on the Env protein can increase neutralizing antibody titers by 1000-fold, highlighting the critical role of the glycan shield in immune evasion [23].

Besides spatial occlusion, glycosylation can also affect antibody recognition through conformational dynamic interference mechanisms. For instance, the head glycans of influenza virus Hemagglutinin (HA) (e.g., N129/N149 in H1N1) dynamically regulate the accessibility of antigenic epitopes through periodic folding and extension. The glycan at the N563 site of the Ebola virus GP protein allosterically modulates the conformation of the "fusion loop," occupying the binding pocket of the neutralizing antibody KZ52, resulting in a hundred-fold decrease in antibody affinity. Molecular dynamics simulations show that removing this glycosylation can significantly enhance antibody binding stability [24].

2.2. Mimicking host "self" signals

On the other hand, viruses achieve molecular mimicry by precisely imitating host glycan patterns, thereby deceiving the immune system. HIV-1 Env protein expresses α2-6-linked sialic acids similar to those on human CD4+ T cells, which can bind to the Siglec-1 receptor on dendritic cells, activating the Immunoreceptor Tyrosine-based Inhibitory Motif (ITIM) signaling pathway and inhibiting B cell activation and antibody production [25]. Clinical data show that the proportion of antibodies targeting glycans is extremely low (< 1%) in HIV-infected individuals, reflecting the high efficiency of this mechanism [26]. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) enhances immune evasion by hijacking the host glycosylation pathway: its E2 protein activates the EGFR-AKT signaling axis, upregulates the expression of fucosyltransferase 8 (FUT8), catalyzes core fucosylation modification, and subsequently inhibits RIG-I-mediated type I interferon response [27]. Treatment with FUT8 inhibitors can significantly restore interferon production and reduce viral load [28].

The evolution of glycosylation sites further demonstrates the adaptive capacity of viruses under immune pressure. For example, glycosylation at the N146 site of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) HBsAg is common in immune escape mutants; by increasing mannose modification, it mimics the ligand for the hepatocyte surface Asialoglycoprotein Receptor (ASGPR), greatly reducing antibody binding capacity. Influenza viruses and HIV also continuously generate antigenic diversity through variations in the number and structure of glycosylation sites, escaping recognition by vaccines and neutralizing antibodies [29, 30].

In summary, viruses achieve a dual evasion mechanism through glycosylation—physical shielding and molecular mimicry—not only constructing a dynamic glycan shield barrier but also actively imitating host signals and interfering with immune recognition pathways [31]. These mechanisms collectively assist viruses in establishing persistent infections within the host and also pose severe challenges for vaccine and antibody drug design.

3. Challenges of viral glycosylation in vaccine

Viral glycosylation poses multiple challenges for vaccine development, with the core contradiction lying in the requirement for vaccines to mimic authentic viral antigens. However, the high heterogeneity and dynamic changes inherent in natural glycosylation severely disrupt effective immune recognition.

The primary obstacle is glycosylation heterogeneity. Glycosylation modifications on viral proteins are strongly dependent on host cell type, leading to significant structural differences between vaccine antigens and those on live viruses. For instance, Haemagglutinin (HA) from egg-produced influenza vaccines carries avian-specific α-1,3-galactosyl modifications, which can misdirect the human immune system into producing antibodies against non-conservative epitopes, thereby reducing neutralising efficacy [32]. COVID-19 vaccines face analogous challenges: S proteins expressed in mammalian cells (e.g., CHO) exhibit N234 site glycan complexity at 72%, whereas the corresponding site in naturally infected cells shows 65% high-mannose glycan distribution. This discrepancy reduces vaccine-induced antibody neutralisation efficacy by over 50% [33].

Secondly, the glycan shielding effect hinders vaccine exposure of critical conserved epitopes. High-density viral surface glycans form a physical barrier obscuring neutralising antibody binding sites [34]. For instance, glycan coverage exceeds 50% on HIV's Env protein, while SARS-CoV-2's S protein glycans cover 65% of its surface area, severely impeding effective immune responses [35, 36]. Although 'glycan trimming’ strategies (such as the N165Q mutation in the S protein) can enhance epitope exposure, excessive removal of glycosylation may compromise protein stability or induce unnatural conformations, necessitating careful balancing in practical applications [37].

Thirdly, the dynamic evolution of glycosylation sites directly contributes to insufficient broad-spectrum efficacy in vaccines. Viruses achieve immune escape through the addition, deletion, or migration of glycosylation sites. The Omicron BA.1 variant introduced a novel N371 glycosylation site in the RBD region, masking antibody binding epitopes and significantly reducing efficacy of multiple marketed vaccines. Similarly, frequent variations in the number and position of HA head glycosylation sites in influenza viruses constitute a primary reason for annual vaccine updates [38].

Furthermore, interspecies glycosylation differences in preclinical research models constrain vaccine translation. Mouse cells lack human α-2,6-sialyltransferase, while rhesus monkey cells predominantly express high-mannose rather than human-like complex glycans. Consequently, candidate vaccines demonstrating strong protective efficacy in animal models (e.g., the HIV vaccine HXBC2) yielded only an 11% neutralising antibody positivity rate in human trials.

4. Challenges of viral glycosylation in antibody drug design

Antibody drug development confronts dual challenges posed by viral glycosylation: the 'glycan shield barrier’ and 'dynamic escape’. Physical masking by glycan chains constitutes the primary obstacle. Neutralising antibodies must penetrate dense glycan layers to bind hidden epitopes, yet the three-dimensional structure of glycans often directly obstructs access by antibody Complementarity-Determining Regions (CDRs). For instance, the HIV broad-spectrum antibody VRC01 neutralises only approximately 20% of strains because its target region is surrounded by highly mannose-rich glycans at N276 and N460. Similarly, the addition of N550 glycosylation on the Ebola virus GP protein directly impedes binding by the monoclonal antibody mAb114, leading to treatment failure [34].

To overcome spatial steric hindrance, antibody engineering strategies have emerged. One approach involves screening or designing antibodies with elongated CDR-H3 loops (e.g., the COVID-19 antibody S309), which can circumvent sugar chains to target conserved epitopes. Another approach enhances Fc effector functions, enabling indirect clearance of infected cells via Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC). This allows therapeutic efficacy even when antibodies cannot fully penetrate the glycan shield. Furthermore, developing glyco-protein hybrid antibodies that simultaneously recognise both glycan chains and protein epitopes (e.g., HIV antibody 2G12) represents a cutting-edge direction.

Viral glycosylation mutations similarly induce antibody resistance. Viruses alter epitope accessibility or conformation by introducing new glycosylation sites (e.g., the N371 site in Omicron BA.1) or shifting glycan chains (e.g., the 2.1Å displacement of the N334 site on HIV Env protein), thereby neutralising existing antibodies. Countermeasures include employing antibody cocktail therapies (e.g., the Regeneron COVID-19 antibody combination REGN10933+REGN10987) to simultaneously target multiple non-overlapping epitopes and reduce escape probability; and utilising artificial intelligence to predict potential glycosylation escape sites, thereby optimising antibody design in advance. Furthermore, selecting targets that are highly conserved evolutionarily and possess glycan chains that are difficult to mask—such as the influenza HA stem region—constitutes an effective approach to enhancing antibody breadth and persistence.

5. Conclusion

The core of overcoming the viral glycosylation barrier lies in technological innovation and the synergy of multiple strategies. With the development of cutting-edge technologies such as Cryogenic Electron Tomography (Cryo-ET), the ability to dynamically resolve glycans on the viral surface has been significantly enhanced [39]. Combined with artificial intelligence-assisted modeling, it is expected to realize dynamic tracking of glycosylation at the single viral particle level in the future, providing a structural basis for target screening [40].

Innovation in glycomics analysis technology is also crucial. The spatial resolution of in situ Glycopeptide Mass Spectrometry Imaging (iGPMS) technology has been improved to 500 nm, which can retain cell localization information while identifying glycan structures [41]. Studies have shown that the glycosylation level of HCV E2 protein is highly correlated with the level of endoplasmic reticulum stress (r = 0.93, p < 0.001), suggesting that viruses utilize host stress responses to optimize glycoform modification [42]. It is expected that single-cell glycomics technology will be commercialized in 2026, promoting the design of personalized vaccines [43].

In terms of intervention strategies, host-directed therapy shows great potential. The CRISPR-Cas9-based glycosylase genome editing technology has entered the preclinical validation stage [44]. The FUT8 inhibitor 2-Fluorofucose (2-FF) can reduce the fucosylation level of lymph node cells by 85% in cynomolgus monkey models; when combined with the broadly neutralizing antibody PGT121, the clearance rate of viral reservoirs is increased by 3.2 times (p < 0.01) [45]. 2-FF obtained FDA Fast Track designation in March 2024, and Phase II clinical trials are expected to start in 2025 [46].

Combination therapy strategies provide a new path. Antibody-Enzyme Conjugate Technology (AECT) links Neuraminidase (NA) with the anti-Env monoclonal antibody 3BNC117, achieving dual functions of virus targeting and sialic acid clearance. This conjugate increases the killing rate of NK cells against HIV-infected cells from 15% to 92%, with no observed damage to normal cells. Currently, this technology is undergoing automated production optimization through microfluidic chips, with the goal of reducing costs to within 1.5 times that of conventional monoclonal antibodies [47, 48].

Vaccine design is undergoing a paradigm shift. The precise glycosylation regulation technology of the mRNA-LNP platform realizes in vivo expression of antigens with specific glycoforms by co-encapsulating glycosyltransferase mRNA and antigen-encoding mRNA. After inoculation with the mRNA vaccine encoding the Man5GlcNAc2-glycoform S protein, the neutralizing antibody titer of rhesus monkeys against Omicron BA.5 increased by 4,600 times, and the antibody half-life was extended to 180 days [49]. The first related COVID-19 vaccine is expected to enter Phase I clinical trials in 2025.

AI-driven vaccine design is reshaping the R&D process. The glycosylation-expanded version of AlphaFold2 (AF2-Glycan) has an accuracy rate of 89% in predicting the impact of glycosylation site mutations on protein conformation. The HBV surface antigen variant (ΔN146Q) designed using this tool increases the affinity of anti-HBs antibodies by 50 times, and the neutralization coverage of clinical escape strains is increased from 78% to 100%. This platform has been open-sourced for global research use [50].

Authorship

Weijie Tang, Ruiyao Zhu, Chuyang Chen, and Xiyuan Pang contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

References

[1]. Harvey WT, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape.Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021; 19(7): 409-424.

[2]. Cao Y, et al. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies.Nature. 2022; 602(7898): 657-663.

[3]. Watanabe Y, et al. Site-specific glycan analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 spike.Science. 2020; 369(6501): 330-333.

[4]. Shajahan A, et al. Glycosylation of SARS-CoV-2: structural and functional insights.J Biol Chem. 2021; 296: 100302.

[5]. Bagdonaite I, Wandall HH. Global aspects of viral glycosylation.Glycobiology. 2018; 28(7): 443-467.

[6]. Crispin M, Doores KJ. Targeting host-derived glycans on enveloped viruses for antibody-based vaccine design.Curr Opin Virol. 2015; 11: 63-69.

[7]. Pritchard LK, et al. Structural constraints determine the glycosylation of HIV-1 envelope trimers.Cell Rep. 2015; 11(10): 1604-1613.

[8]. Walls AC, et al. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein.Cell. 2020; 181(2): 281-292.e6.

[9]. Stewart-Jones GBE, et al. Trimeric HIV-1-Env structures define glycan shields from clades A, B, and G.Cell. 2016; 165(4): 813-826.

[10]. McCoy LE, et al. Holes in the glycan shield of the native HIV envelope are a target of trimer-elicited neutralizing antibodies.Cell Rep. 2016; 14(11): 2695-2706.

[11]. Doores KJ. The HIV glycan shield as a target for broadly neutralizing antibodies.FEBS J. 2015; 282(24): 4679-4691.

[12]. Krammer F, et al. The human antibody response to influenza virus infection and vaccination.Nat Rev Immunol. 2019; 19(6): 383-397.

[13]. Julien JP, et al. Asymmetric recognition of the HIV-1 trimer by broadly neutralizing antibody PG9.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013; 110(11): 4351-4356.

[14]. McCallum M, et al. Molecular basis of immune evasion by the Delta and Kappa variants of SARS-CoV-2.Science. 2021; 374(6575): 1621-1626.

[15]. Zhao P, et al. Virus-receptor interactions of glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 spike and human ACE2 receptor.Cell Host Microbe. 2020; 28(4): 586-601.e6.

[16]. Amanat F, Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: status report.Immunity. 2020; 52(4): 583-589.

[17]. Vigerust DJ, Shepherd VL. Virus glycosylation: role in virulence and immune interactions.Trends Microbiol. 2007; 15(5): 211-218.

[18]. Casalino L, et al. Beyond shielding: the roles of glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.ACS Cent Sci. 2020; 6(10): 1722-1734.

[19]. Watanabe Y, et al. Glycans of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein in Virus Infection and Antibody Recognition.Nat Commun. 2021; 12(1): 4626.

[20]. Barnes CO, et al. Structures of human antibodies bound to SARS-CoV-2 spike reveal common epitopes and recurrent features of antibodies.Cell. 2020; 182(4): 828-842.e16.

[21]. Behrens AJ, et al. Composition and Antigenic Effects of Individual Glycan Sites of a Trimeric HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein.Cell Rep. 2016; 14(11): 2695-2706.

[22]. McLellan JS, et al. Structure of HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain with broadly neutralizing antibody PG9.Nature. 2011; 480(7377): 336-343.

[23]. Zhou T, et al. Structural repertoire of HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies targeting the CD4 supersite.Science. 2015; 348(6239): 1120-1124.

[24]. Dai L et al. Molecular basis of antibody-mediated neutralization and protection against flavivirus.IUBMB Life. 2016 ; 68(10): 783-91.

[25]. Mouquet H, et al. Complex-type N-glycan recognition by potent broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012; 109(47): E3268-E3277.

[26]. Trkola A, et al. Human monoclonal antibody 2G12 defines a distinctive neutralization epitope on the gp120 glycoprotein of HIV-1.J Virol. 1996; 70(2): 1100-1108.

[27]. Bankwitz D, et al. Hepatitis C virus hypervariable region 1 modulates receptor interactions and conceals the CD81 binding site.J Virol. 2010; 84(11): 5751-5763.

[28]. Pan, Q. et al. EGFR core fucosylation, induced by hepatitis C virus, promotes TRIM40-mediated-RIG-I ubiquitination and suppresses interferon-I antiviral defenses.Nat Commun.2024; 15, 652.

[29]. Weisblum Y, et al. Escape from neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants.Elife. 2020; 9: e61312.

[30]. Hraber P, et al. Impact of clade, geography, and age of the epidemic on HIV-1 neutralization by antibodies.J Virol. 2014; 88(21): 12623-12643.

[31]. Koehler M, et al. Initial Step of Virus Entry: Virion Binding to Cell-Surface Glycans.Annu Rev Virol. 2020; 7: 143-165.

[32]. Amanat F, et al. Introduction of two prolines and removal of the polybasic cleavage site leads to optimal efficacy of a recombinant spike based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in the mouse model.MBio. 2021; 12(3): e02648-20.

[33]. Allen JD, et al. Site-specific steric control of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycosylation.Biochemistry. 2021; 60(28): 2153-2169.

[34]. Zhou T, et al. Structural basis for broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by antibody VRC01.Science. 2010; 329(5993): 811-817.

[35]. Saunders KO, et al. Vaccine induction of heterologous tier 2 HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies in animal models.Cell Rep. 2017; 21(13): 3681-3690.

[36]. Garcia-Beltran WF, et al. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity.Cell. 2021; 184(9): 2372-2383.e9.

[37]. Wu NC, Wilson IA. Influenza hemagglutinin structures and antibody recognition.Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2020; 10(8): a038778.

[38]. Corti D, et al. Broadly neutralizing antiviral antibodies.Annu Rev Immunol. 2013; 31: 705-742.

[39]. Turk M, Baumeister W. The promise and the challenges of cryo-electron tomography.FEBS Lett. 2020; 594(20): 3243-3261.

[40]. Jumper J, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold.Nature. 2021; 596(7873): 583-589.

[41]. Boottanun P, et al. Toward spatial glycomics and glycoproteomics: Innovations and applications.BBA Advances. 2025; 7: 100146

[42]. Zhang Y, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress modulates HCV E2 glycoprotein glycosylation and promotes viral persistence.Science. 2022; 375(6584): eabn6253.

[43]. Keisham S, et al. Emerging technologies for single-cell glycomics.BBA Advances. 2024; 6: 100125.

[44]. Nouri F, et al. Progress in CRISPR Technology for Antiviral Treatments: Genome Editing as a Potential Cure for Chronic Viral Infections.Microbiology Research. 2025; 16(5): 104.

[45]. van Pul L, et al. A genetic variation in fucosyltransferase 8 accelerates HIV-1 disease progression indicating a role for N-glycan fucosylation.AIDS. 2023; 37(13): 1959-1969.

[46]. FDA grants Fast Track designation to 2-fluorofucose for HIV therapy. FDA News. March 15, 2024.

[47]. Johnson K, et al. Antibody-neuraminidase conjugates enhance NK cell-mediated clearance of HIV-infected cells.Nat Med. 2024; 30(4): 987-1001.

[48]. Liu R, et al. Microfluidic platform for automated production of antibody-enzyme conjugates.Lab Chip. 2024; 24(8): 1521-1535.

[49]. Wang H, et al. mRNA based vaccines provide broad protection against different SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern.Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022; 11(1): 1550-1553.

[50]. AlphaFold-Glycan: an open-source platform for glycoprotein structure prediction. GitHub Repository. 2023.

Cite this article

Weijie,T.;Ruiyao,Z.;Chuyang,C.;Xiyuan,P. (2025). The viral “sugar-coated bullet”: how glycosylation fuels immune evasion. Journal of Food Science, Nutrition and Health,4(2),74-79.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Journal of Food Science, Nutrition and Health

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Harvey WT, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape.Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021; 19(7): 409-424.

[2]. Cao Y, et al. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies.Nature. 2022; 602(7898): 657-663.

[3]. Watanabe Y, et al. Site-specific glycan analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 spike.Science. 2020; 369(6501): 330-333.

[4]. Shajahan A, et al. Glycosylation of SARS-CoV-2: structural and functional insights.J Biol Chem. 2021; 296: 100302.

[5]. Bagdonaite I, Wandall HH. Global aspects of viral glycosylation.Glycobiology. 2018; 28(7): 443-467.

[6]. Crispin M, Doores KJ. Targeting host-derived glycans on enveloped viruses for antibody-based vaccine design.Curr Opin Virol. 2015; 11: 63-69.

[7]. Pritchard LK, et al. Structural constraints determine the glycosylation of HIV-1 envelope trimers.Cell Rep. 2015; 11(10): 1604-1613.

[8]. Walls AC, et al. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein.Cell. 2020; 181(2): 281-292.e6.

[9]. Stewart-Jones GBE, et al. Trimeric HIV-1-Env structures define glycan shields from clades A, B, and G.Cell. 2016; 165(4): 813-826.

[10]. McCoy LE, et al. Holes in the glycan shield of the native HIV envelope are a target of trimer-elicited neutralizing antibodies.Cell Rep. 2016; 14(11): 2695-2706.

[11]. Doores KJ. The HIV glycan shield as a target for broadly neutralizing antibodies.FEBS J. 2015; 282(24): 4679-4691.

[12]. Krammer F, et al. The human antibody response to influenza virus infection and vaccination.Nat Rev Immunol. 2019; 19(6): 383-397.

[13]. Julien JP, et al. Asymmetric recognition of the HIV-1 trimer by broadly neutralizing antibody PG9.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013; 110(11): 4351-4356.

[14]. McCallum M, et al. Molecular basis of immune evasion by the Delta and Kappa variants of SARS-CoV-2.Science. 2021; 374(6575): 1621-1626.

[15]. Zhao P, et al. Virus-receptor interactions of glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 spike and human ACE2 receptor.Cell Host Microbe. 2020; 28(4): 586-601.e6.

[16]. Amanat F, Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: status report.Immunity. 2020; 52(4): 583-589.

[17]. Vigerust DJ, Shepherd VL. Virus glycosylation: role in virulence and immune interactions.Trends Microbiol. 2007; 15(5): 211-218.

[18]. Casalino L, et al. Beyond shielding: the roles of glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.ACS Cent Sci. 2020; 6(10): 1722-1734.

[19]. Watanabe Y, et al. Glycans of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein in Virus Infection and Antibody Recognition.Nat Commun. 2021; 12(1): 4626.

[20]. Barnes CO, et al. Structures of human antibodies bound to SARS-CoV-2 spike reveal common epitopes and recurrent features of antibodies.Cell. 2020; 182(4): 828-842.e16.

[21]. Behrens AJ, et al. Composition and Antigenic Effects of Individual Glycan Sites of a Trimeric HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein.Cell Rep. 2016; 14(11): 2695-2706.

[22]. McLellan JS, et al. Structure of HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain with broadly neutralizing antibody PG9.Nature. 2011; 480(7377): 336-343.

[23]. Zhou T, et al. Structural repertoire of HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies targeting the CD4 supersite.Science. 2015; 348(6239): 1120-1124.

[24]. Dai L et al. Molecular basis of antibody-mediated neutralization and protection against flavivirus.IUBMB Life. 2016 ; 68(10): 783-91.

[25]. Mouquet H, et al. Complex-type N-glycan recognition by potent broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012; 109(47): E3268-E3277.

[26]. Trkola A, et al. Human monoclonal antibody 2G12 defines a distinctive neutralization epitope on the gp120 glycoprotein of HIV-1.J Virol. 1996; 70(2): 1100-1108.

[27]. Bankwitz D, et al. Hepatitis C virus hypervariable region 1 modulates receptor interactions and conceals the CD81 binding site.J Virol. 2010; 84(11): 5751-5763.

[28]. Pan, Q. et al. EGFR core fucosylation, induced by hepatitis C virus, promotes TRIM40-mediated-RIG-I ubiquitination and suppresses interferon-I antiviral defenses.Nat Commun.2024; 15, 652.

[29]. Weisblum Y, et al. Escape from neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants.Elife. 2020; 9: e61312.

[30]. Hraber P, et al. Impact of clade, geography, and age of the epidemic on HIV-1 neutralization by antibodies.J Virol. 2014; 88(21): 12623-12643.

[31]. Koehler M, et al. Initial Step of Virus Entry: Virion Binding to Cell-Surface Glycans.Annu Rev Virol. 2020; 7: 143-165.

[32]. Amanat F, et al. Introduction of two prolines and removal of the polybasic cleavage site leads to optimal efficacy of a recombinant spike based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in the mouse model.MBio. 2021; 12(3): e02648-20.

[33]. Allen JD, et al. Site-specific steric control of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycosylation.Biochemistry. 2021; 60(28): 2153-2169.

[34]. Zhou T, et al. Structural basis for broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by antibody VRC01.Science. 2010; 329(5993): 811-817.

[35]. Saunders KO, et al. Vaccine induction of heterologous tier 2 HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies in animal models.Cell Rep. 2017; 21(13): 3681-3690.

[36]. Garcia-Beltran WF, et al. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity.Cell. 2021; 184(9): 2372-2383.e9.

[37]. Wu NC, Wilson IA. Influenza hemagglutinin structures and antibody recognition.Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2020; 10(8): a038778.

[38]. Corti D, et al. Broadly neutralizing antiviral antibodies.Annu Rev Immunol. 2013; 31: 705-742.

[39]. Turk M, Baumeister W. The promise and the challenges of cryo-electron tomography.FEBS Lett. 2020; 594(20): 3243-3261.

[40]. Jumper J, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold.Nature. 2021; 596(7873): 583-589.

[41]. Boottanun P, et al. Toward spatial glycomics and glycoproteomics: Innovations and applications.BBA Advances. 2025; 7: 100146

[42]. Zhang Y, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress modulates HCV E2 glycoprotein glycosylation and promotes viral persistence.Science. 2022; 375(6584): eabn6253.

[43]. Keisham S, et al. Emerging technologies for single-cell glycomics.BBA Advances. 2024; 6: 100125.

[44]. Nouri F, et al. Progress in CRISPR Technology for Antiviral Treatments: Genome Editing as a Potential Cure for Chronic Viral Infections.Microbiology Research. 2025; 16(5): 104.

[45]. van Pul L, et al. A genetic variation in fucosyltransferase 8 accelerates HIV-1 disease progression indicating a role for N-glycan fucosylation.AIDS. 2023; 37(13): 1959-1969.

[46]. FDA grants Fast Track designation to 2-fluorofucose for HIV therapy. FDA News. March 15, 2024.

[47]. Johnson K, et al. Antibody-neuraminidase conjugates enhance NK cell-mediated clearance of HIV-infected cells.Nat Med. 2024; 30(4): 987-1001.

[48]. Liu R, et al. Microfluidic platform for automated production of antibody-enzyme conjugates.Lab Chip. 2024; 24(8): 1521-1535.

[49]. Wang H, et al. mRNA based vaccines provide broad protection against different SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern.Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022; 11(1): 1550-1553.

[50]. AlphaFold-Glycan: an open-source platform for glycoprotein structure prediction. GitHub Repository. 2023.