1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is the function of a company to take responsibility for its actions. Companies are involved in corporate social responsibility (CSR), in such a manner that they can perform actions that are socially responsible and do things that create some positive impact on society. It is a self-regulation action, taken to match the culture of the company and the target of the business. Organisations communicate these efforts to all their stakeholders, both internal and external.

Shareholder activism is a form of using votes and shares by investors to influence a firm's policies and practices. This approach provides a formula through which shareholders can demand more consideration of dimensions of CSR that make a firm more relevant to its activities [1]. The diverse cross-cultural attitudes toward CSR in the USA and across many countries indicate that expectations concerning CSR may not be uniform across cultures. CSR will, therefore, be differently conceived and considered more than strategically in a context of more or less altruistic considerations from one culture to another.

In this regard, CSR evolves as the dramatic qualifying moments of corporate strategy devised within the rapidly changing sphere of the world business environment that deeply touch the internal dimensions of management of the companies and the stakeholders including investors and customers.

1.2. Research Objectives

To that end, the research will be guided by the following objectives;

• Assess the challenges that attribute to a disconnect between CSR and shareholder activism

• Analyse the potential for using CSR as a tool for cross-cultural communication and engagement with stakeholders.

• Propose recommendations on how share-holder activism and cross-cultural management practices can be incorporated to a company’s CSR initiatives

1.3. Research Questions

To achieve the research’s objectives, the following questions will need to be answered:

• What are the challenges attributed to a disconnect between CSR and shareholder activism?

• What is the potential for using CSR as a tool for cross-cultural communication and engagement with stakeholders?

• What recommendations can be put forward on how share-holder activism and cross-cultural management practices can be incorporated into a company’s CSR initiatives?

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Agency Theory

The major theory of shareholder activism is Agency theory, by which a shareholder activist acts as an external governance monitor. In the context of agency theory, activist investors are expected to concentrate on the companies with governance and performance problems [2]. Nevertheless, activist investors often face the challenge of choosing between targets that have significant agency and performance issues and those where their efforts are more likely to be successful, due to constraints in resources and time. Scholars specialising in social movements argue that the corporate opportunity structure has a significant role in determining the timing and location of activity within social movement settings [2].

2.2. The Tripple Bottom Line Theory

"Triple bottom line" describes the metaphor in business, which paints an obligation that pertains to a business monitoring its social and environmental influence besides meeting the set standard of unequivocal success- which is financial success. This pushes the companies to look beyond just seeking profit and venture into other implications of their activities. The triple bottom line can be broken down into three key parts—economic profit, the health and well-being of society (people), and environmental sustainability [3]. Such step classifications would be applied so that the companies could imagine ecological responsibility and what harm they could be doing. It enables organizations to later apply sustainability conduct throughout their organization's activities.

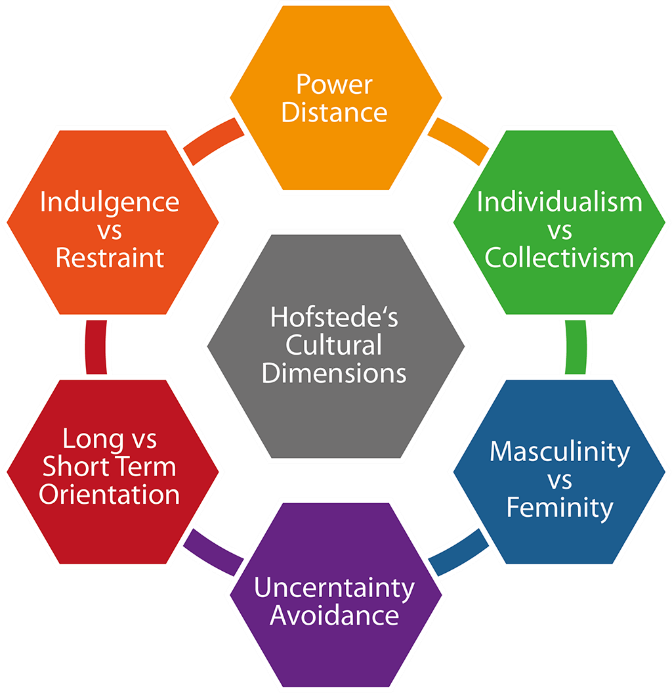

2.3. Geert Hofstede framework for evaluating culture

The Cultural Dimensions Theory was developed by Geert Hofstede in 1980, and it was founded on a broad survey conducted by Hofstede during the 1960s and 1970s. The study analysed the diversity of values among different divisions of IBM, a multinational computer manufacturing company. It helps in understanding the differences in culture across countries and different ways of doing business in different cultural settings [4]. In simple terms, this framework helps to distinguish different national cultures, analyse cultural elements, assess their impact on social practices, and facilitate communication in such areas as trade and diplomacy.

Hofstede delineated six distinct characteristics that serve to determine culture: PDI, Collectivism vs. Individualism, Uncertainty Avoidance Index, Masculinity vs. Femininity, Short-Term vs. Long-Term Orientation, Restraint vs. Indulgence.

Figure 1: Geert Hofstede's framework for evaluating culture

2.4. Obligations that Constitute CSR

The four obligations that constitute corporate social responsibility (CSR) are: the economic responsibility to make profits, the legal responsibility to adhere to rules and regulations, the ethical responsibility to do what's right even when not required by law, and the philanthropic responsibility to contribute to society's projects even when they're independent of the business's operations [5].

Economic responsibility is a vital part of corporate social responsibility (CSR) which points out that business should be profitable that means be value creating, revenue generating, investing, innovating, creating jobs, and paying tax which will be utilized in providing public services. Profits allow firms to invest in operations, communities, and economic growth. The legal duty entails that all businesses adhere to laws and regulations in areas such as environment, labour, consumer protection, and taxes. Observing the law fosters openness, responsibility, morals, good behaviour, and upholds trust with stakeholders.

Ethical duty requires organisations to do what is moral beyond legal compliance, to treat employees fairly, and to ensure consumer safety and well-being as well as to be socially and environmentally proactive even outside their operations. Ethical conduct builds trust among the stakeholders and enables societal development. Finally, philanthropic responsibility means that firms should allocate their resources to community projects and other important social issues that do not relate to their business operations. Philanthropy is a demonstration of social responsibility and allows companies to help with issues such as poverty, education, and preservation.

2.5. Insights on CSR and Shareholder Activism

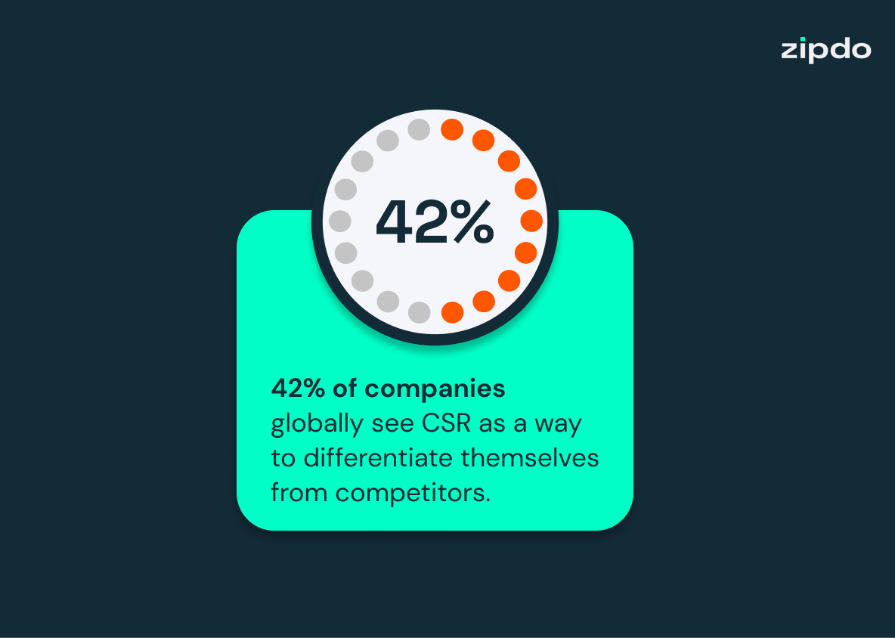

Research conducted revealed that; 42% of global companies believe CSR is a differentiation tactic [6].

Figure 2: Insight 1

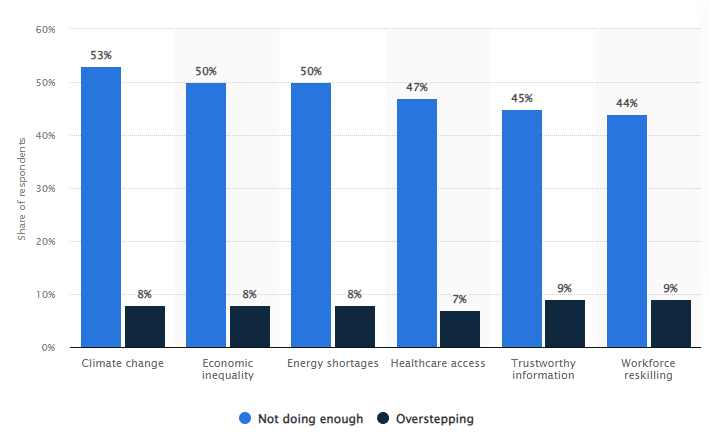

Additional research revealed that according to customers climate change; economic inequalities and energy shortages were the sectors in which CSR efforts were under performing [7].

Figure 3: Insight 2

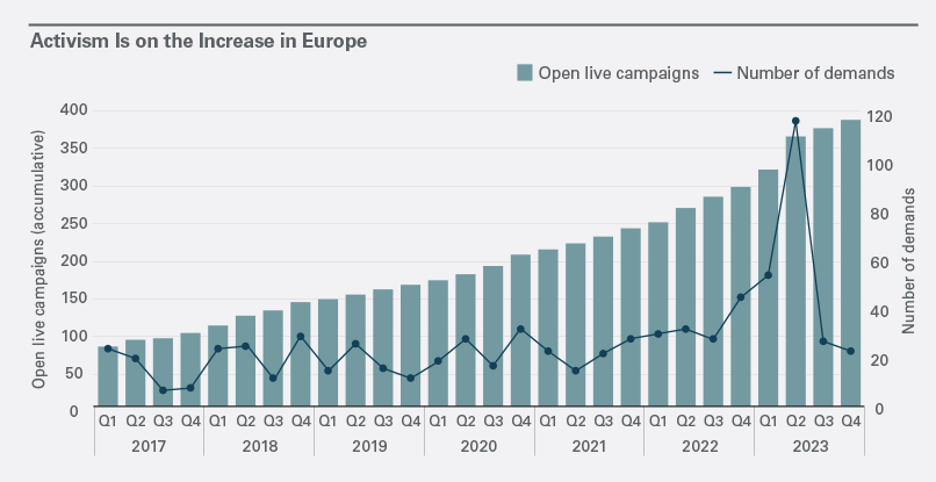

In Europe, it was showed that European corporations listed on stock exchanges are under growing pressure from activist investors. Over the last six years, there has been a consistent increase in the number of activist campaigns initiated against European firms [8]. In 2023, there was a surge in the number of new public activist campaigns, reaching a record high. Additionally, many new activist participants emerged in the field.

Figure 4: Insight 3

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

The qualitative research design was chosen to steer the data collection and analysis for the research. Such a research design was chosen because the research questions are exploratory which need to uncover about how these three elements of CSR, shareholder activism and cross-cultural management practices are interdependent with one another [9]. A qualitative approach helped in exhaustive study of the research problem revealing subjective experiences and view-points of the main stakeholders in the area of CSR implementation, shareholder activism, and cross-cultural management.

3.2. Sampling and Population

The researcher employed the purposive sampling technique to get the respondents for the study. Purposive sampling is the process of picking units for a sample in which they are chosen by their particular qualities, rather than by being selected at random. It was chosen because of its cost efficiency and the goodness of effectively getting the right respondents for the data collection. The research respondents were ten, and included experts and experienced professionals in CSR, shareholder activism, and cross-cultural management such as CSR professionals, corporate executives, shareholder activists, and cross-cultural management consultants.

3.3. Data Collection

There will be ten participants in the semi-structured interviews; that is, the interview held will be open-ended but restricted to a set of prior agreed upon issues. The use of open-ended questions ensures the semi-structured nature and also helps close disaggregated gaps during this phase [9]. The fully detailed interview questions are attached in the annexe below.

The interview sessions were carried out in a serene and neutral place so that the members could give their accurate and coherent views of the study. Thereafter, the transcripts of the interview sessions were given to the research members, and they were asked to carry out the member checking to check on the data taken during the interview to see if they were correct and credible for the study.

3.4. Data Analysis

The data analysis process was based on a six-stage model, which included familiarisation with the data, initial coding, searching for themes, reviewing and defining themes, naming the themes and creating the final report [10]. Use of direct quotes from participants were employed to back up and illuminate the presumed themes, which made the findings more credible and richer. The data that had been gathered was analysed with reference to case studies in order to obtain a rich and varied data set that facilitated a comprehensive understanding of the research problem in various organisational and cultural contexts.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

Throughout the whole research process, ethical issues were put into the highest consideration. All participants were asked to give their consent before commencement of the interviews, and their privacy and confidentiality were upheld by deleting personal identifiers and using pseudonyms.

4. Research Results

4.1. Challenges that cause a disconnect between CSR and shareholder activism

It was the unanimous view of all the participants that issues can arise when a company’s corporate social responsibility actions are not in line with the expectations of the shareholder activists. One of the themes that persist until the end of the interviews is the unmeasurable character of the benefits gained from CSR activities. Participant F remarked, “The positive impacts like better reputation and motivated employees are hard to quantify in numbers, making it tough to show shareholders focused on share prices the real value of CSR.” It was pointed out that companies find it difficult to prove the real value of CSR to shareholders who are mainly concerned with metrics such as stock price performance.

One other theme that was noticed was that consumer and public expectations concerning CSR practices are dynamic. Participant B commented that “Companies don’t keep up with the always-evolving consumer and stakeholder expectations. This is a perfect illustration of the dissonance between CSR efforts and shareholder activism.

4.2. Analyse the potential for using CSR as a tool for cross-cultural communication and engagement with stakeholders.

That CSR can be an effective tool for companies to manage cross cultural communication and deal with stakeholders from different backgrounds was agreed upon by all the participants. In which this could be done, a common theme was the aspect of utilizing CSR to bring about a harmonizing factor and trust creation tool. Participant J posited that “CSR initiatives may provide a platform in which companies can reach out to diverse stakeholders all over the world in one go thereby leading to understanding and trust among stakeholders”.

Participants appreciated the innate power of CSR initiatives to go beyond cultural barriers and appeal to various kinds of stakeholders. Integration of corporate values and actions within the framework of socially responsible and ethical principles allows organizations to build a common vision which will be embraced by many cultures. Through this shared understanding, stakeholders are able to interpersonally communicate and virtually discussing the cultural attributes that are present and relevant to the society, whereby they perceived the organization as one that is working towards making a positive change.

4.3. Suggest strategies on how share-holder activism and cross-cultural management practices can be integrated into a company’s CSR initiatives.

All respondents emphasized the importance of integrating both shareholder activism and cross-cultural management practices into a company’s CSR initiatives. Two themes were found. One of these was that companies should lead in addressing the concerns raised by shareholder activists. The second one was the application of culturally relevant programs [11].

Responding to the challenges posed by the activist shareholders was seen as a critical feature of the organization. Hearing the view from participant H that “companies should be proactive in engaging with shareholder activists and addressing their concerns regarding the CSR initiatives, this open dialogue can bridge the gap between CSR efforts and the shareholder’s approach.

The second theme raised by the participants was the requirements of introducing cultural initiatives, part of a corporate CSR plan. Participant C noted that “Effective cross-cultural management in CSR initiatives is rooted in the understanding and respect of the different cultural contexts within which the company operates. Cross-cultural management practices help to make CSR initiatives culturally-adaptive, inclusive, relevant, and more impactful in various cultural environments in which they are implemented. Culture-sensitive initiatives demonstrate a respect for the local traditions, values, and practices and strengthen ties with local communities and stakeholders.

5. Discussion

When CSR is not in line with shareholder activism

The difficulty of companies in demonstrating to shareholders, who see the relevance of items such as stock price performance only, the true value of CSR is in agreement with the challenge of [12], which pointed out that the intangible benefits of corporate social responsibility (CSR), such as enhanced reputation and staff motivation, cannot be measured in monetary terms. The challenge is often ascribed to the subjective character of these advantages and their lack of direct impact on financial success. The scholarly literature on corporate social responsibility (CSR) often highlights the significance of qualitative metrics and narratives as effective means of capturing the value of CSR initiatives.

Moreover, the findings of relatively wide consumer and public expectations in changing the activities of CSR are also congruent with prior studies on CSR and their notion of the corporate social license to operate. This perception means that businesspersons should keep reforming their CSR policies so that they are in touch with the changing customer's or the whole public's perceptions. The literature concluded that there were adaptive effects that the firms should exhibit towards societal expectations and that the difficult and complex matters with respect to efforts should not be overlooked by how firms are beginning to handle their stewardship reports.

CSR as a measure of cross-cultural interaction and stakeholder’s participation.

The finding that corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities may even transcend cultural borders is consistent with the study of [13]. That is, companies can come up with the most appealing story that is likely to be sold by the majority of stakeholders. They can only achieve this if the values at an organizational and operational level are congruent with the standards stipulated as ethical and socially responsible [13]. This series of narratives can equally raise effective intercultural interactions collectively to address the natural urge towards a world that would be better, delivering the heritage for eternity.

6. Recommendation and Conclusion

6.1. Recommendation

CSR provides a formal avenue to channel for company’s engagements with stakeholders whose composition brings diversity in culture. This may be realized through community educational programs on environmental sustainability; in line with that, cultural beliefs are being tackled by funds channelled through the preference for community developments, which serve since programs that are tailored to meet such cultures' needs as identified by the stakeholders in the place. In addition to that, CSR establishes cross-cultural communication and collaboration. This partnering approach strengthens relationships between business and stakeholders and also contributes to the general intention of reaching development that is both inclusive and sustainable.

6.2. Conclusion

The study has unveiled the linkages between CSR, shareholder activism, and cross-cultural management practice. While the intangible benefits of CSR and the meeting of various stakeholders' expectations raise challenges in precise definition, the results indicate that CSR is seen as an integrative factor that fosters cross-cultural communication and mutual trust building among various stakeholder groups. Through proactive engagement with shareholder activists and culture-sensitive implementation of CSR initiatives, companies can achieve the equilibrium of complexity in which they have to meet stakeholder demands and the associated positive impacts in different cultural contexts. In the end, adopting CSR as a strategic instrument for cross-cultural involvement and stakeholder cooperation will help improve the image of a company and promote the worldwide sustainable and inclusive development.

References

[1]. Hambrick, D. C., & Wowak, A. (2019). CEO Sociopolitical Activism: A Stakeholder Alignment Model. Academy of Management Review, 46(1). https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2018.0084

[2]. Li, F., Li, T., & Minor, D. (2016). CEO power, corporate social responsibility, and firm value: a test of agency theory. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 12(5), 611–628. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijmf-05-2015-0116

[3]. Pan, X., Sinha, P., & Chen, X. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and eco-innovation: The triple bottom line perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(1), 214–228. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2043

[4]. Halkos, G., & Skouloudis, A. (2016, February 1). Cultural dimensions and corporate social responsibility: A cross-country analysis. Mpra.ub.uni-Muenchen.de. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/69222

[5]. Minoja, M., Kocollari, U., & Cavicchioli, M. (2022). Exploring differences of corporate social responsibility perceptions and expectations between eastern and western countries: Emerging patterns and managerial implications. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 22(2), 147059582211122. https://doi.org/10.1177/14705958221112253

[6]. Eser, A. (2023, June 13). Exposing the Truth: Corporate Social Responsibility Statistics in 2023 • ZipDo. ZipDo. https://zipdo.co/statistics/corporate-social-responsibility/

[7]. Dencheva, V. (2023, March 22). Global consumers’ attitudes towards CSR 2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1372794/consumer-attitudes-corporate-social-responsibility-worldwide/

[8]. Grumberg, A., Knighton, G., & Toms, S. (2024, February 23). Skadden Discusses Increasing Shareholder Activism in Europe | CLS Blue Sky Blog. The CLS Blue Sky Blog. https://clsbluesky.law.columbia.edu/2024/02/23/skadden-discusses-increasing-shareholder-activism-in-europe/

[9]. Lanka, E., Lanka, S., Rostron, A., & Singh, P. (2021). Why We Need Qualitative Research in Management Studies. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 25(2). https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-7849rac2021200297.en

[10]. Alsaawi, A. (2014, July). A Critical Review of Qualitative Interviews. Papers.ssrn.com. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2819536

[11]. Stahl, G. K., Miska, C., Lee, H.-J., & De Luque, M. S. (2017). The upside of cultural differences. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 24(1), 2–12. emerald. https://doi.org/10.1108/ccsm-11-2016-0191

[12]. Bozos, K., King, T., & Koutmos, D. (2022). CSR and Firm Risk: Is Shareholder Activism a Double-Edged Sword? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(11), 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15110543

[13]. Michelon, G., Rodrigue, M., & Trevisan, E. (2020). The marketization of a social movement: Activists, shareholders and CSR disclosure. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 80, 101074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2019.101074

Cite this article

Jiang,X. (2024). The Dynamics of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Shareholder Activism and Cross-Cultural Management. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,93,66-74.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Management Research and Economic Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Hambrick, D. C., & Wowak, A. (2019). CEO Sociopolitical Activism: A Stakeholder Alignment Model. Academy of Management Review, 46(1). https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2018.0084

[2]. Li, F., Li, T., & Minor, D. (2016). CEO power, corporate social responsibility, and firm value: a test of agency theory. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 12(5), 611–628. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijmf-05-2015-0116

[3]. Pan, X., Sinha, P., & Chen, X. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and eco-innovation: The triple bottom line perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(1), 214–228. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2043

[4]. Halkos, G., & Skouloudis, A. (2016, February 1). Cultural dimensions and corporate social responsibility: A cross-country analysis. Mpra.ub.uni-Muenchen.de. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/69222

[5]. Minoja, M., Kocollari, U., & Cavicchioli, M. (2022). Exploring differences of corporate social responsibility perceptions and expectations between eastern and western countries: Emerging patterns and managerial implications. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 22(2), 147059582211122. https://doi.org/10.1177/14705958221112253

[6]. Eser, A. (2023, June 13). Exposing the Truth: Corporate Social Responsibility Statistics in 2023 • ZipDo. ZipDo. https://zipdo.co/statistics/corporate-social-responsibility/

[7]. Dencheva, V. (2023, March 22). Global consumers’ attitudes towards CSR 2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1372794/consumer-attitudes-corporate-social-responsibility-worldwide/

[8]. Grumberg, A., Knighton, G., & Toms, S. (2024, February 23). Skadden Discusses Increasing Shareholder Activism in Europe | CLS Blue Sky Blog. The CLS Blue Sky Blog. https://clsbluesky.law.columbia.edu/2024/02/23/skadden-discusses-increasing-shareholder-activism-in-europe/

[9]. Lanka, E., Lanka, S., Rostron, A., & Singh, P. (2021). Why We Need Qualitative Research in Management Studies. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 25(2). https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-7849rac2021200297.en

[10]. Alsaawi, A. (2014, July). A Critical Review of Qualitative Interviews. Papers.ssrn.com. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2819536

[11]. Stahl, G. K., Miska, C., Lee, H.-J., & De Luque, M. S. (2017). The upside of cultural differences. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 24(1), 2–12. emerald. https://doi.org/10.1108/ccsm-11-2016-0191

[12]. Bozos, K., King, T., & Koutmos, D. (2022). CSR and Firm Risk: Is Shareholder Activism a Double-Edged Sword? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(11), 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15110543

[13]. Michelon, G., Rodrigue, M., & Trevisan, E. (2020). The marketization of a social movement: Activists, shareholders and CSR disclosure. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 80, 101074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2019.101074