1. Introduction

A paper by the Pew Research Center called “As Partisan Hostility Grows, Signs of Frustration With the Two-Party System” claims that ‘artisan polarization has long been a fact of political life in the United States.’ This points out the circumstances in America, where partisan conflict is getting more severe. It does cause multiple problems around the society and slows administrative efficiency [1].

Admittedly, partisan conflicts slow down administrative efficiency. However, our research found that the reason for this phenomenon is that politicians take advantage of the outrage phenomenon and try to manipulate the public. We found that different parties use social media to publish news in their favor, which can reinforce extreme perceptions and provide electoral advantages. That is to say, the platform provides a platform for politicians to show themselves, and politicians also rely on the platform to influence voters. It is precisely because the platform colludes with politicians that society has formed a political polarization.

The paper "As Partisan Hostility Grows, Signs of Frustration With the Two-Party System" by the Pew Research Center highlights the longstanding presence of partisan polarization as a significant aspect of political life in the United States [1]. This observation sheds light on the increasingly severe circumstances of partisan conflict in America, which has led to numerous societal problems and a decline in administrative efficiency.

While it is undeniable that partisan conflicts contribute to the slowdown of administrative efficiency, our research indicates that the underlying cause lies in politicians exploiting the phenomenon of outrage and manipulating the public. We have discovered that different political parties utilize social media as a platform to disseminate news and information that aligns with their interests. This practice tends to reinforce extreme perceptions among the public and provides electoral advantages for the parties involved. Consequently, the platform becomes a powerful tool for politicians to showcase themselves while also enabling them to exert influence over voters. The collusion between politicians and the platform has fostered a pervasive political polarization.

We formed a 4 part dynamic model. Understanding the intricate interplay between these four components requires a comprehensive analysis of their interactions, motivations, and consequences. Researchers and analysts face the daunting task of untangling the complex web of information flows, biases, and manipulations. By examining the role of social media, the press, politicians, and the public, we can begin to grasp the dynamics at play and gain a clearer understanding of the current situation in America.

In conclusion, as the severity of partisan conflict in America increases, it has led to significant societal problems and a decline in administrative efficiency. While partisan conflicts definitely contribute to this situation, our research shows that politicians exploiting outrage and manipulating the public also play a crucial role. The four-part dynamic model comprising social media, the press, politicians, and the public provides a framework for analyzing the interactions and information flows within this system. However, comprehending the complexity of this model remains a challenging task, as the components interact in multifaceted ways, making it difficult to obtain a clear understanding of the current situation in America.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Public’s Reliance on Social Media and its Effects

As the development of the social network has accelerated, people increasingly fall onto social media as their primary source of information. Studies indicate that about two-thirds of U.S. adults get news on social media platforms, with two-thirds of Facebook users and six in 10 Twitter users getting news on the platform [2]. The shift from traditional media to social media for news consumption profoundly affects the public and the media landscape. On the positive side, it has democratized information, allowing more voices to be heard and facilitating real-time communication [3]. However, this reliance on social media has also led to concerns about the spread of misinformation and the creation of echo chambers that reinforce existing beliefs and biases [4,5]. A study conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2018 found that approximately 57% of social media news consumers expect the news they see on social media to be largely inaccurate [3]. Furthermore, the algorithms that determine what users see may skew perspectives, leading to a narrow view of world events [4,6]. The long-term effects on public discourse, critical thinking, and democracy remain areas of concern and study for scholars, policymakers, and media practitioners [5,7].

2.2. The mechanisms and algorithms

Since people fall completely onto social media, their thoughts are heavily affected by the media. Research shows that a fake news flag on a headline aligned with users’ opinions triggered cognitive activity that could be associated with increased semantic memory retrieval, false memory construction, or increased attention [8]. This points out that people tend to focus on the news that fits with their assumption, whether it's right or not [9]. Another study reveals that for a headline of average length, each additional negative word increased the click-through rate by 2.3% [10]. These findings hint at the basic psychological mechanisms of polarization [5].

The algorithms that govern social media platforms play a significant role in these effects [7,11]. By curating content based on user preferences and previous interactions, algorithms create a "filter bubble" that reinforces pre-existing beliefs and isolates users from opposing views [11]. These personalized feeds can lead to a skewed perception of reality and make constructive dialogue between different ideological groups more difficult [7]. Moreover, the emphasis on engaging content, driven by the algorithms of social media platforms, has led to the prevalence of sensationalism and emotional manipulation in headlines [12]. This further drives click-through rates but potentially undermines thoughtful discourse and critical thinking [13]. Understanding the complex interplay between human psychology and the underlying algorithms that drive content delivery on social media platforms is an essential step in addressing the broader challenges of misinformation and polarization in modern society [7,14].

2.3. The Effect of the News on the politics

Social media platforms, especially those based in America, can exert significant influence on the political systems of various states. A paper by Guy Schleffer and Benjamin Miller identifies four different effects that social media can have: a weakening effect on strong democratic regimes, an intensifying effect on strong authoritarian regimes, a radicalizing effect on weak democratic regimes, and a destabilizing effect on weak authoritarian regimes [15]. The mechanisms behind these effects include the rapid spread of information, the amplification of extreme voices, and the erosion of shared public discourse [16]. In another instance, Diana Owen's research reveals that fake news stories, playing to people’s preexisting beliefs, were efficiently spread through Facebook, Snapchat, and other social media during the 2016 U.S. election [17]. These conspiracy theories, hoaxes, and lies reached millions of voters, potentially influencing the outcome [18,19].

The implications of these findings are substantial. Social media platforms can be tools for both democratic engagement and manipulation. They can foster transparency and civic participation but also amplify misinformation and deepen divisions [16]. For example, a study by Allcott and Gentzkow found that fake news on Facebook could have influenced voting behavior in the 2016 U.S. Presidential election [18]. In authoritarian regimes, social media may reinforce state control by censoring dissent and spreading propaganda [20]. Alternatively, social media's role in challenging authoritarian rule has been evidenced in more recent protests and movements, reflecting its capacity to enable political change [21]. The multifaceted impact of social media on political systems underscores the need for responsible governance of these platforms, critical media literacy among citizens, and ongoing research into the complex interplay between technology, information, and political power [22].

2.4. Assessment

All the texts above rigorously analyze the interaction and effect between any two parts of society. However, barely any articles focus on the chain or the tunnel that the information flows in. And where and why, as well as how, this information gets polluted. Our research will stand on the solid ground of previous analysis and give out a four part model to depict a picture of what’s going on.

3. Discussion & Analysis

Table 1: Four-Part.

| 1st agenda | Characteristics |

Public | 1. Obtain information 2. Self-expression | 1. Affected by news affects politician |

Social Media | 1. Provide platform

| 1. Drive by the revenue

2. Face privacy, security and spread of misinformation issue |

Presses | 1. Gives out info | 2. Drive by political affluence 3. Core commitment to in-depth investigation, critical analysis, and public engagement |

Politician | 1. Publish policy

2. Need vote from the public to maintain their social power | 1. Affected by votes 2. Aiming to persuade the public and derive power from public support 3. Supposed to represent their country rather than their party |

3.1. Public

Table 1 is a chart that organizes the characteristics and No. 1 agenda for each part of the society. As shown in Table 1, the public, essentially people worldwide, is incentivized to receive information from various perspectives because not all information is readily accessible. The public also desires communication, companionship, and self-expression to share their viewpoints and attributes with others. Furthermore, the public wields significant power to influence election results, although their thoughts can easily be swayed or controlled by information found on the internet.

3.2. Social Media

Social media platforms are designed to foster global communication, collaboration, and real-time content sharing. They enable features such as profile creation, commenting, multimedia posting, and personalized feeds curated through algorithms. With accessibility across various devices, social media connects individuals and businesses, allowing them to express opinions, engage in dialogues, and promote brands. However, challenges may arise related to privacy, security, and spreading misinformation.

3.3. Presses

The press, a cornerstone of democratic societies, emphasizes accuracy, objectivity, fairness, and independence. It is dedicated to sharing accurate information globally without injecting subjective opinions and serves as a watchdog over governmental activities. Upholding standards of integrity, transparency, and responsibility, the press, even in the digital age, maintains its core commitment to in-depth investigation, critical analysis, and public engagement.

3.4. Politicians

Politicians are characterized by their devotion to party principles, policy advocacy, and comprehension of governmental structure. Their work requires robust communication skills for interaction with the public, media, and fellow politicians. Ethical politicians prioritize transparency, integrity, and accountability, aiming to persuade the public and derive power from their support. While striving to balance various stakeholders' needs and foster consensus, politicians might also encounter challenges related to self-interest or party allegiance.

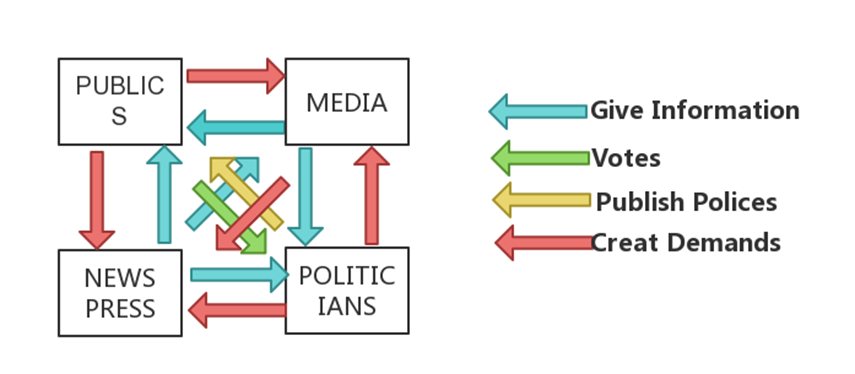

Figure 1: The model before the internet.

4. The basic information flow before the internet

Before the internet was introduced, people got information either by reading newspapers directly or watching TV and so did politicians. This forms a special way of how the information is finally passed through society and how it improves the election of the leader of the people, and Figure 1 is a visual representation of this process.

Media outlets and news presses play a crucial role in providing information to both the public and politicians. They not only serve as news sources but also rely on subscriptions and public attention to generate revenues.

The public relies on these media sources to gather information about political candidates, enabling them to form a comprehensive image of each candidate. With this knowledge, individuals can make informed decisions when choosing their leaders. Gathering information from various media outlets empowers the public to critically evaluate the policies and ideas put forth by candidates.

By examining the platforms and proposals each candidate presents, individuals can assess which ones align with their values and aspirations. This informed decision-making process is vital for selecting leaders who will work towards bettering both the people and the country.

In turn, the candidates themselves are motivated to come up with innovative and impactful policy ideas. They understand that to gain the support of the public, their proposals must address the needs and concerns of the people. As a result, candidates strive to develop policies that will benefit the country as a whole, as well as improve the lives of individual citizens. This dynamic interaction between candidates and the public fosters a healthy democratic process, where ideas are refined and ultimately implemented for the betterment of society.

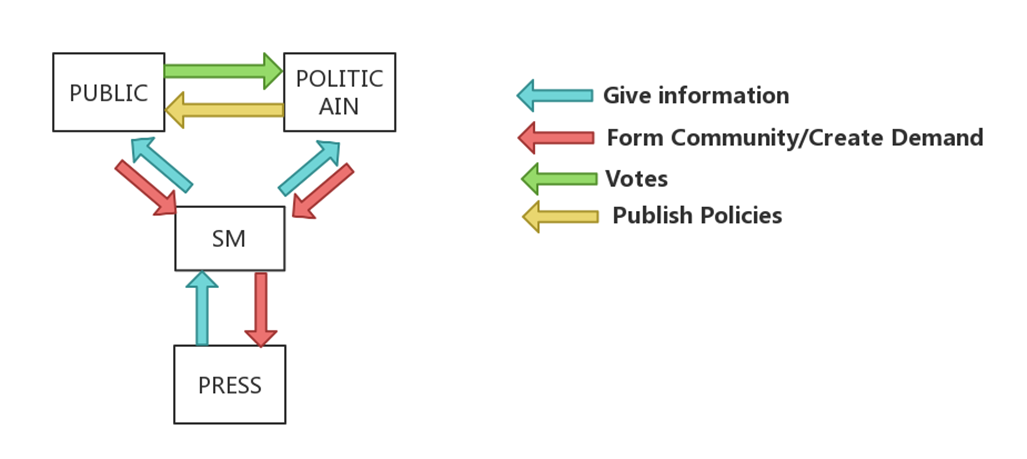

Figure 2: The ideal model with the internet.

5. The information flow after the internet, ideally

The relationship between news presses, social media platforms, the public, and politicians has become increasingly interconnected in the modern information landscape. Figure 2 can help us to understand how these parts interact with each other. (After the internet was invented) News presses play a vital role by providing information to social media platforms, creating a dependency between the two. Social media platforms rely on this content to attract public attention, as the constant influx of news articles and updates keeps users engaged. To optimize the user experience, social media platforms employ algorithms that filter and recommend information from news presses, further reinforcing the public's reliance on these platforms for news consumption.

This symbiotic relationship between social media platforms and news presses has significant implications for the public. As algorithms curate and personalize the information presented to users, individuals increasingly rely on social media as their primary news source. The convenience and accessibility of social media make it a preferred platform for many to stay informed about current events and political developments.

Politicians, recognizing the power and reach of social media platforms, have increasingly turned to these platforms as essential tools for spreading their influence and garnering support. Social media gives politicians direct access to the public, allowing them to communicate their policies and messages without relying solely on traditional media outlets. The real-time feedback and insights from social media platforms enable politicians to gauge public sentiment and tailor their strategies accordingly. This close connection between politicians and social media platforms enables more efficient policy-making and governance, as politicians can better understand and address the needs and concerns of the public.

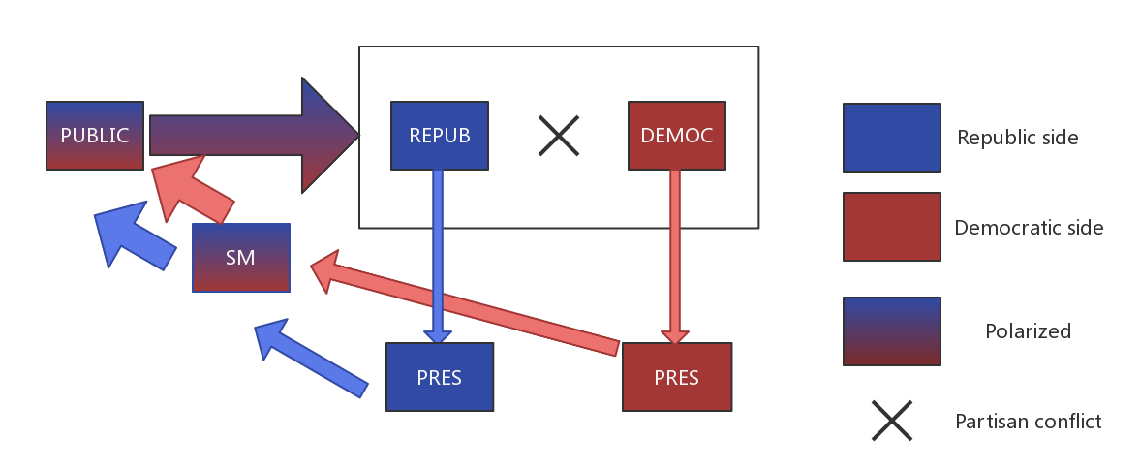

Figure 3: The realistic model.

6. How the model goes in the real life

In today's complex and interconnected world, the prevalence of media polarization and the echo chamber effect have become pressing issues. It’s a complicated issue. Thus, we will use Figure 3 to address what we believe about how these parts of society work with one another. The ownership of different press media outlets by political parties has contributed to the worsening of this phenomenon. We can see examples like Fox News, often associated with the Republican Party, and CNN, which leans towards the left side of the political spectrum. These media organizations actively produce content that discredits their opponents while praising their affiliations, perpetuating a sense of bias and partisanship.

The rise of social media platforms has further amplified the impact of media polarization. Using algorithms, these platforms personalize content delivery based on user's preferences and browsing history. While this may seem convenient and tailored to individual interests, it often leads to the creation of echo chambers within online communities. Echo chambers are digital spaces where individuals are exposed primarily to information that aligns with their existing beliefs, reinforcing their preconceived notions and shielding them from alternative perspectives.

The consequences of the echo chamber effect are far-reaching and pose significant challenges to our society. It deepens existing divisions, heightens political polarization, and undermines the possibility of rational discourse and meaningful conversations. By confining ourselves within these echo chambers, we limit our exposure to diverse opinions and hinder our ability to think critically and consider alternative viewpoints. Instead of evaluating political candidates based on their abilities to represent the best interests of the country and enact positive change, voters are increasingly inclined to support politicians who cater to their outrage and inflame their emotions.

This trend has profound implications for the democratic process. When voters prioritize emotional manipulation over rational decision-making, the very foundations of governance are at risk. It becomes more challenging to foster an environment that values transparency, accountability, and the pursuit of the common good. The democratic ideals of inclusivity, compromise, and open dialogue are undermined as citizens retreat into their comfort zones of reinforced beliefs.

The repercussions of media polarization and the echo chamber effect go beyond deepening societal divisions and impeding rational discourse. They also have a detrimental impact on the efficiency of governance and the quality of policies. As the connection between the people and politicians breaks down, politicians become disconnected from the true demands and needs of the population. This lack of awareness hinders effective policy-making and undermines the very foundation of America's democratic system. Moreover, with the focus on emotional manipulation rather than rational decision-making, the administrative costs rise, and the working efficiency of the government decreases. Ultimately, these consequences further erode the trust and confidence that citizens place in their political institutions, creating an adverse environment for progress and growth.

7. A possible solution to a polarized society, according to the analysis

According to our analysis, if we can eliminate the influence of political power on the press, it would significantly mitigate polarized thinking. By removing the input of biased and polarizing thoughts from the media landscape, we can create a more balanced and objective discourse. This would help foster a healthier information environment where diverse perspectives can be heard and considered. Without the constant reinforcement of partisan narratives, individuals would have the opportunity to engage with a wider range of ideas, promoting critical thinking and reducing the prevalence of polarized beliefs in society.

In addition to addressing the influence of the government, another crucial step in tackling media polarization is to address the algorithms used by social media platforms. By preventing these algorithms from sending and promoting polarized news exclusively to specific groups of people, we can disrupt the creation of echo-chambered communities. Implementing algorithmic transparency and accountability measures would ensure that individuals are exposed to a diverse range of content and perspectives. This would encourage cross-ideological engagement, critical thinking, and cultivating a more inclusive and informed society. By curbing the amplification of polarized content, we can create a more balanced and constructive information ecosystem for the benefit of all users.

8. Conclusion

The main goal of the current study was to determine the major cause of the outrage economy by analyzing the cycle. This essay provides a deeper insight into how the public, politicians, and press, as well as social media, interact. As the essay has demonstrated, the pollution of the press caused by the political interventions is the key cause of the outrage economy. The essay has also shown that balancing polluted media with clean media or stopping the algorithm from tearing people apart might be feasible solutions. However, we lack a deeper investigation of the feasible solution to the outrage economy, and we hope later researchers can deeply investigate it.

References

[1]. Nadeem, R. (2022, August 9). As partisan hostility grows, signs of frustration with the two-Party system. Pew Research Center - U.S. Politics & Policy. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2022/08/09/as-partisan-hostility-grows-signs-of-frustration-with-the-two-party-system/

[2]. Jeffrey Gottfried (2016). Pew Research Center's Journalism & Media. "News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2016."

[3]. Mitchell, A., Gottfried, J., Stocking, G., Walker, M., & Fedeli, S. (2018). "The Evolving Role of News on Twitter and Facebook." Pew Research Center.

[4]. Eli Pariser (2011). "The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You."

[5]. Sunstein, C.R. (2017). "#Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media."

[6]. Tufekci, Z. (2015). "Algorithmic Harms beyond Facebook and Google: Emergent Challenges of Computational Agency." Colorado Technology Law Journal, 13, 203.

[7]. Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). "Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics."

[8]. Moravec, P. L., Minas, R. K., & Dennis, A. R. (2018). Fake News on Social Media: People Believe What They Want to Believe When it Makes No Sense at All. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3269541

[9]. Pennycook, Gordon and Rand, David G., Fighting Misinformation on Social Media Using Crowdsourced Judgments of News Source Quality (January 29, 2019). Pennycook, G., & Rand. D. G. (2019). Fighting misinformation on social media using crowdsourced judgments of news source quality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1806781116, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3118471 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3118471

[10]. Claire E. Robertson, Nicolas Pröllochs, Kaoru Schwarzenegger, Philip Pärnamets, Jay J. Van Bavel & Stefan Feuerriegel (2023). "Emotional Language and Its Impact on Social Media Engagement."

[11]. Zuboff, S. (2019). "The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power."

[12]. Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). "The Spread of True and False News Online." Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151.

[13]. Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., & Cook, J. (2020). "The Conspiracy Theory Handbook." Center for Climate Change Communication.

[14]. Allcott, H., Gentzkow, M., & Yu, C. (2019). "Trends in the Diffusion of Misinformation on Social Media." Research & Politics, 6(2), 2053168019848554.

[15]. Guy Schleffer, Benjamin Miller (2021). "Social Media and Political Systems: Weakening Democracy, Intensifying Authoritarianism, Radicalizing Democracy, and Destabilizing Authoritarianism."

[16]. Tucker, J. A., Guess, A. M., Barberá, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A. A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social Media, Political polarization, and Political Disinformation: A review of the Scientific literature. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3144139

[17]. Owen, D. (2018). "The New Media's Role in Politics." In M. McKinney & A. S. Carlin (Eds.), Political Communication in Real Time: Theoretical and Applied Research Approaches.

[18]. Hunt Allcott, Matthew Gentzkow (2017). "Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211-236.

[19]. Lazer, D., Baum, M., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S. A., Sunstein, C. R., Thorson, E., Watts, D. J., & Zittrain, J. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

[20]. King, G., Pan, J., & Roberts, M. E. (2017). How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts for Strategic Distraction, Not Engaged Argument. American Political Science Review, 111(3), 484–501. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055417000144

[21]. Altman, M. Tufekci, Z.: Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest . Voluntas 29, 884–885 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9927-0

[22]. Lewis, B., & Marwick, A. (2017). Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online. “Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online.” https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-05/apo-nid135936.pdf

Cite this article

Yang,D.;Lee,Y.;Luo,Y.;Li,J.;Xu,J. (2024). Who’s the Bad Guy? Politician, News Press, or Social Media?. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,89,75-83.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Nadeem, R. (2022, August 9). As partisan hostility grows, signs of frustration with the two-Party system. Pew Research Center - U.S. Politics & Policy. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2022/08/09/as-partisan-hostility-grows-signs-of-frustration-with-the-two-party-system/

[2]. Jeffrey Gottfried (2016). Pew Research Center's Journalism & Media. "News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2016."

[3]. Mitchell, A., Gottfried, J., Stocking, G., Walker, M., & Fedeli, S. (2018). "The Evolving Role of News on Twitter and Facebook." Pew Research Center.

[4]. Eli Pariser (2011). "The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You."

[5]. Sunstein, C.R. (2017). "#Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media."

[6]. Tufekci, Z. (2015). "Algorithmic Harms beyond Facebook and Google: Emergent Challenges of Computational Agency." Colorado Technology Law Journal, 13, 203.

[7]. Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). "Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics."

[8]. Moravec, P. L., Minas, R. K., & Dennis, A. R. (2018). Fake News on Social Media: People Believe What They Want to Believe When it Makes No Sense at All. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3269541

[9]. Pennycook, Gordon and Rand, David G., Fighting Misinformation on Social Media Using Crowdsourced Judgments of News Source Quality (January 29, 2019). Pennycook, G., & Rand. D. G. (2019). Fighting misinformation on social media using crowdsourced judgments of news source quality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1806781116, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3118471 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3118471

[10]. Claire E. Robertson, Nicolas Pröllochs, Kaoru Schwarzenegger, Philip Pärnamets, Jay J. Van Bavel & Stefan Feuerriegel (2023). "Emotional Language and Its Impact on Social Media Engagement."

[11]. Zuboff, S. (2019). "The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power."

[12]. Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). "The Spread of True and False News Online." Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151.

[13]. Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., & Cook, J. (2020). "The Conspiracy Theory Handbook." Center for Climate Change Communication.

[14]. Allcott, H., Gentzkow, M., & Yu, C. (2019). "Trends in the Diffusion of Misinformation on Social Media." Research & Politics, 6(2), 2053168019848554.

[15]. Guy Schleffer, Benjamin Miller (2021). "Social Media and Political Systems: Weakening Democracy, Intensifying Authoritarianism, Radicalizing Democracy, and Destabilizing Authoritarianism."

[16]. Tucker, J. A., Guess, A. M., Barberá, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A. A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social Media, Political polarization, and Political Disinformation: A review of the Scientific literature. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3144139

[17]. Owen, D. (2018). "The New Media's Role in Politics." In M. McKinney & A. S. Carlin (Eds.), Political Communication in Real Time: Theoretical and Applied Research Approaches.

[18]. Hunt Allcott, Matthew Gentzkow (2017). "Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211-236.

[19]. Lazer, D., Baum, M., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S. A., Sunstein, C. R., Thorson, E., Watts, D. J., & Zittrain, J. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

[20]. King, G., Pan, J., & Roberts, M. E. (2017). How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts for Strategic Distraction, Not Engaged Argument. American Political Science Review, 111(3), 484–501. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055417000144

[21]. Altman, M. Tufekci, Z.: Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest . Voluntas 29, 884–885 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9927-0

[22]. Lewis, B., & Marwick, A. (2017). Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online. “Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online.” https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-05/apo-nid135936.pdf