1. Introduction

Engaging in donations not only brings about considerable benefits to society but also yields numerous advantages for individuals, encompassing enhanced mental and physical well-being. Research has consistently highlighted the positive correlation between charitable actions and improved health outcomes [1-3]. Numerous charitable organizations grapple with the task of selecting an appealing product that resonates with potential donors. In this context, strategic marketing and product design play pivotal roles. Studies by Peterson and Smith underscore the importance of creating a connection between the charitable product and the target audience's values and preferences. Tailoring the product's appearance to align with these factors significantly enhances its appeal and drives increased donations.

One of the prominent product attributes is "cuteness." The phenomenon known as the "cuteness factor" has garnered significant attention in recent academic discourse. Researchers (have demonstrated that products featuring adorable or endearing elements not only capture attention but also evoke positive emotions [4,5]. When people see a baby, their facial muscles associated with positive emotions are automatically activated, and similar emotional responses occur when people see cute animals or even inanimate object. Hence impulsive spending behavior. Consumers get the product not only for its functional benefit, but also for the emotional experience that is integrated with the product [6]. These experiences may be related to the emotional bonding between some of the physical features of the product and its consumer. Past research found that product that can elicit positive emotions will encourage donating behavior [7]. Therefore, in this study, we propose that cute product can increase donating behavior.

To test this hypothesis and explore the mechanism, we conducted an experiment. Participants were randomly allocated to a 2 by 2 (High vs. Low price & Cute vs. Ordinary product) experiment design. Participants were shown a cake and then we measured participants’ pro-social motivation. At the end, they expressed their willingness to donate. We found that cute products can elicit pro-social motivation, and thus increase donating behaviour.

The findings of this research yield multifaceted contributions to the existing literature. Firstly, it unveils the pivotal role of product characteristics, particularly cuteness, in eliciting pro-social motivation among consumers. This sheds light on the potential of visually pleasing elements to serve as catalysts for heightened pro-social behaviors in charitable contexts. Secondly, the study advances our understanding of the interplay between product pricing and consumer donating behavior. By exploring the impact of different price points on consumers' decisions to contribute, the research provides insights into the economic considerations influencing charitable actions. Collectively, these contributions enhance our comprehension of consumer behavior in the realm of charitable giving and offer practical implications for organizations seeking to optimize fundraising strategies.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Cute product and prosocial motivation

We argue that exposure to cute product will increase consumers’ prosocial motivation with the two reasons as follow. First, cuteness is associated with a more other-directed focus [8]. This orientation towards others cultivates a greater likelihood of developing sympathy. Pro-social behavior, encompassing actions that alleviate another's needs or enhance their well-being [9], is thereby stimulated.

Second, the perception of cuteness would elicit a mental representation of fun. When people have positive affect, they are more likely to do good for others. Positive affect, as established in prior research on the perception-behavior link, correlates with an increased likelihood of altruistic action [10]. Cuteness is proposed to activate brain networks associated with emotion and pleasure, triggering empathy and compassion [11]. The positive affect derived from the perception of fun aligns with a rich body of literature over the past three decades, illustrating that positive feelings foster helpful and generous behaviors, such as charitable donations and volunteering [12].

Therefore, we propose through the prosocial motivation consumers would like to consume more cute product for helping others in the society.

H1: Exposure to cute product increase consumers’ prosocial motivation.

2.2. Cute product and willingness to donate

Exposure to cute products amplifies consumers' inclination to donate, driven by two key factors. Firstly, product attributes serve as activators of perceptions that significantly influence subsequent behaviour. In this study, particular emphasis is placed on cute products, which evoke a perception of vulnerability. The observation of vulnerability naturally triggers donating behaviour, as evidenced by the well-established phenomenon where advertisements featuring vulnerability prompt increased donations to charities. Hence, the presence of cute products correlates with heightened donating behaviours among customers.

Secondly, cute products serve as primers for a mental representation imbued with fun and playfulness. Research by Dunn et al. demonstrates that experiences of fun and playfulness increase the likelihood of individuals spending money on others [13]. Such expenditures, in turn, induce happiness, creating a positive spiral effect. Furthermore, customers derive enjoyment not only from the act of giving but also from the satisfaction of their own needs, such as indulging in the delightful experience of consuming the cake. This reinforcement of positive affect during decision-making contributes to a lasting positive disposition towards charitable actions. Therefore, we propose:

H2: Exposure to cute product increase consumers’ willingness to donate.

The mediation role of prosocial motivation

Prosocial motivation—the desire to protect and promote the well-being of others—is distinct from altruism and independent of self-interested motivations. Pro-social motivation serves as a cognitive and emotional mechanism that bridges the gap between the perception of cuteness and the subsequent decision to contribute to a charitable cause. In essence, the positive and empathetic responses evoked by cute products create a motivational impetus, compelling individuals to act in ways that benefit others, manifesting in an increased willingness to donate. Combining Hypotheses 1 and 2, we propose:

H3: Exposure to cute product increase consumers’ willingness to donate and prosocial motivation will mediate the relationship between cuteness and willingness to donate.

3. Method and Results

To test the hypotheses, we conducted a 2(Cute vs. Ordinary)x2 (High price vs. Low Price) between-subject design. Participants were randomly allocated to one condition and they were instructed to read scenarios and make purchasing decisions.

3.1. Participants and Procedure

We recruited180 participants (59.4%female) from Credemo, a Chinese data platform that is similar to Prolific. Among them 68.9% get the Bachelor's degree. The average age was 29.61 years, the standard deviation was 7.47 years.

First, participants were informed that we represent a charitable organization dedicated to aiding those affected by COVID-19 and raising funds through cake sales. Then, they were presented with either a cute cake or an ordinary cake associated with a specific price, depending on the randomly allocated conditions. Then, they were instructed to express their willing to buy the cake. Finally, they indicated their pro-social motivation and demographic details.

3.2. Measures

Cuteness manipulation. Participants viewed either the cute or ordinary cake and rated the extent to which the cakes were cute. The item was measured on a 7-point scale (1: not cute at all, 7: very cute). The manipulation was successful. Participants who viewed the cute cake (Mcute = 5.42, SDcute =1.62) rated significantly higher than those who viewed the neural cake (Mneutral = 3.73, SDneutral =1.32, t (178) = 7.66, p < .001).

Expensiveness manipulation. After participants rated the cuteness of the cakes, they will be asking the question: “To what extent this cake is expensive”. The size of this cake is 6 inches and the price is 240 rmb ( 80 rmb in the cheap condition). The item was measured on a 7-point scale (1: not expensive, 7: very expensive). The manipulation was successful. Participants who viewed the expensive cake (Mexpensive = 5.62, SDexpensive =1.00) rated the manipulation check question significantly higher than those who viewed the cheap cake (Mcheap = 4.72, SDcheap =1.33, t (178) = 5.12, p < .001).

Pro-social motivation. We adapted Grant & Berry’s scale to measure pro-social motivation of donating behaviour [14]. The scale included 4 items. The sample item was “I want to purchase the cake to benefit others.”. The items were rated on a 5-point scale (1: Do not agree at all; 5: Definitely agree). The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.91.

Willingness to buy(donate). We asked participants to what extent they are willing to buy the cake, which will be donated to the charity. The item was measured on a 7-point scale (1: never want to buy, 7: very willing to buy). We also asked about how many cakes they are willing to buy (range: 1-10 or more than 10 cakes).

3.3. Results

We provide descriptive statistics in Table 1.

Table 1: Univariate and Bivariate Statistics for Key Variables

Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

1. Condition: Cuteness | 4.58 | 1.71 | ||||||

2. Condition: Expensiveness | 5.17 | 1.26 | -.26** | |||||

3. Prosocial motivation | 3.82 | 0.98 | .42** | -.32** | ||||

4. Donation | 4.38 | 1.61 | .50** | -.49** | .73** | |||

5. Age | 29.6 | 7.47 | .08 | -.09 | .13 | .24** | ||

6. Gender | 0.59 | 0.49 | -.24** | .14 | -.15* | -.25** | -.05 | |

12.Incomea | 12.86 | 10.02 | .07 | -.16* | .15* | .21** | .03 | -.12 |

Note. N = 180. *p <.05 **p <.01. a thousand yuan.

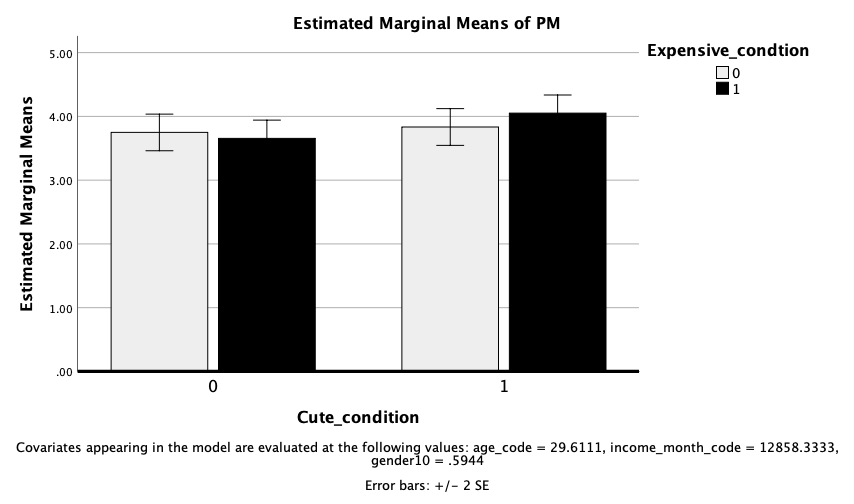

Cuteness and prosocial motivation. We ran an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) on the prosocial motivation, with age, income, and gender as covariates. Analysis revealed that participants who were given the cute cake showed higher level of pro-social motivation (Mcute= 3.95, SDcute = 0.87) than those who were given the normal cake (Mordinary= 3.69, SDordinary= 1.06; F (1, 173) = 2.82, p = .095). The covariates showed a marginally significant effect. These results demonstrate that exposure to cute products has increased the customers’ prosocial motivation, which partially supports Hypothesis 1. The data is Shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The effect of Cuteness and Expensiveness on Prosocial Motivation

Note: For the Cute_Condition, “0” means normal product; “1” means cute product. For Expensice_condition, “0” means the price is low; “1” means the price is high.

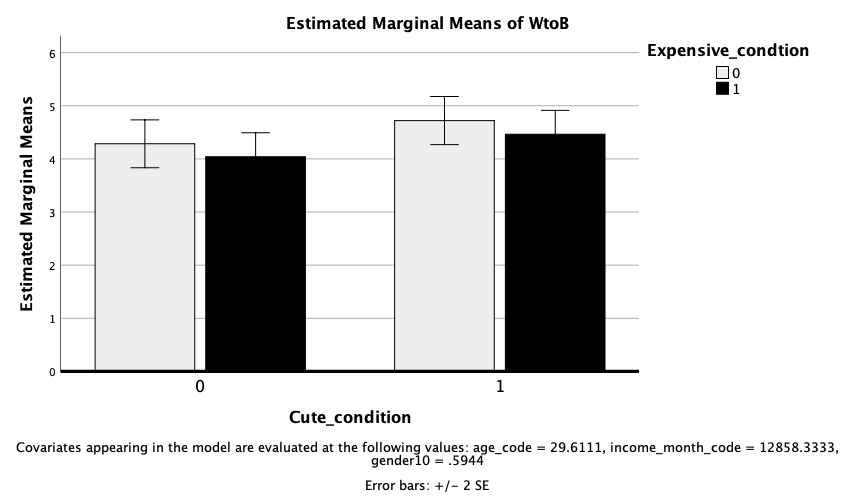

Cuteness and willingness to donate. We also ran an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) on the willingness to donate, with age, income, and gender as covariates. Analysis revealed that participants who were given the cute cake are more willing to donate (Mcute= 4.62, SDcute = 1.48) than those who were given the normal cake (Mnormal= 4.13, SDnormal= 1.71; F (1, 173) = 3.65, p= .058). The covariates showed a marginally significant effect. These results demonstrate that exposure to cute products has increased the customers’ willingness to donate, which supports Hypothesis 2. The data is Shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The effect of Cuteness and Expensiveness on Willingness to Donate

Note: For the Cute_Condition, “0” means normal product; “1” means cute product. For Expensice_condition, “0” means the price is low; “1” means the price is high.

Mediation model. We used PROCESS to test the mediation model using a bootstrap estimation approach with 5000 samples [15,16]. The results indicate the indirect coefficient was significant (b = .22, SE =.05, 95% CI = [.14,.33]) We found that the cuteness of product positively related with the willingness to buy(donate) and prosocial motivation mediated the relationship, which supports Hypothesis 3.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

The research in this article found that consumers are more willing to spend money on cute products than ordinary products through one experiment. The results indicate that regardless of price, people are more likely to donate when they find the product is cute, underscoring the unique appeal of cuteness in consumer choices. This research highlights that the impact of cute products on pro-social motivation.

The theoretical contribution of this research lies in its illumination of the impact of cute products on consumer behavior, particularly in the context of charitable contributions. By conducting a singular experiment, the study establishes a compelling link between consumers' heightened willingness to spend on cute products compared to ordinary ones. Significantly, the findings reveal that this preference for cuteness transcends price considerations, as individuals are more inclined to donate when the product is perceived as cute.

The research enriches existing theoretical frameworks by emphasizing the role of cuteness in stimulating pro-social motivation. The observed phenomenon underscores that the aesthetic appeal of cute products serves as a powerful motivator for individuals to engage in altruistic actions, such as making donations. This contributes to a deeper understanding of the intricate interplay between product characteristics, emotional responses, and pro-social behavior.

In essence, this study extends the theory by elucidating how cuteness functions as a unique and potent factor in shaping consumer choices and, more notably, influencing pro-social motivations. The identified link between cuteness and heightened pro-social behavior provides a valuable theoretical foundation for future research exploring the psychological mechanisms underlying consumer preferences and charitable actions.

Therefore, in conclusion, consumers' donation behavior can be achieved through the cute appearance of the product, the consumer's prosocial motivation, and the consumer's empathy.

References

[1]. Aknin, L. B., & Whillans, A. V. (2021). Helping and happiness: A review and guide for public policy. Social Issues and Policy Review, 15(1), 3-34.

[2]. Liu, W., & Aaker, J. (2008). The happiness of giving: The time-ask effect. Journal of consumer research, 35(3), 543-557.

[3]. Smith, K. E., Norman, G. J., & Decety, J. (2020). Medical students’ empathy positively predicts charitable donation behavior. The journal of positive psychology, 15(6), 734-742.

[4]. Lehmann, Vicky, Elisabeth M. J. Huis in’t Veld, and Ad J. J. M. Vingerhoets (2013), “The Human and Animal Baby Schema Effect: Correlates of Individual Differences,” Behavioural Processes, 94 (March), 99–108.

[5]. Sherman, Gary D., Jonathan Haidt, Ravi Iyer, and James A. Coan (2013), “Individual Differences in the Physical Embodiment of Care: Prosaically Oriented Women Respond to Cuteness by Becoming More Physically Careful,” Emotion, 13 (1), 151–58.

[6]. Crilly, N., Moultrie, J., & Clarkson, P. J. (2004). Seeing things: consumer response to the visual domain in product design. Design studies, 25(6), 547-577.

[7]. Cavanaugh, L. A., Bettman, J. R., & Luce, M. F. (2015). Feeling love and doing more for distant others: Specific positive emotions differentially affect prosocial consumption. Journal of Marketing Research, 52(5), 657-673.

[8]. Lorenz, F. W. (1943). Fattening cockerels by stilbestrol administration. Poultry Science, 22(2), 190-191.

[9]. Schott, C., Neumann, O., Baertschi, M., & Ritz, A. (2019). Public service motivation, prosocial motivation and altruism: Towards disentanglement and conceptual clarity. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(14), 1200-1211.

[10]. Lorenz,Dijksterhuis, A., Smith, P. K., Van Baaren, R. B., & Wigboldus, D. H. (2005). The unconscious consumer: Effects of environment on consumer behavior. Journal of consumer psychology, 15(3), 193-202.

[11]. Shin, J., & Mattila, A. S. (2021). Aww effect: Engaging consumers in “non-cute” prosocial initiatives with cuteness. Journal of Business Research, 126, 209-220.

[12]. Isen, A. M. (1987). Positive affect, cognitive processes, and social behavior. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 20, pp. 203-253). Academic Press.

[13]. Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319(5870), 1687-1688.

[14]. Grant, A. M., & Berry, J. W. (2011). The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Academy of management journal, 54(1), 73-96.

[15]. Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. In White paper (pp. 1–39). Judd & Kenny MacKinnon. https://doi.org/978-1-60918-230-4

[16]. Shrout, P. E. & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422.

Cite this article

Cheng,Y. (2024). Cuteness Catalyst: Fostering Pro-Social Motivation and Enhancing Donating Behaviors . Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,112,13-18.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Economic Management and Green Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Aknin, L. B., & Whillans, A. V. (2021). Helping and happiness: A review and guide for public policy. Social Issues and Policy Review, 15(1), 3-34.

[2]. Liu, W., & Aaker, J. (2008). The happiness of giving: The time-ask effect. Journal of consumer research, 35(3), 543-557.

[3]. Smith, K. E., Norman, G. J., & Decety, J. (2020). Medical students’ empathy positively predicts charitable donation behavior. The journal of positive psychology, 15(6), 734-742.

[4]. Lehmann, Vicky, Elisabeth M. J. Huis in’t Veld, and Ad J. J. M. Vingerhoets (2013), “The Human and Animal Baby Schema Effect: Correlates of Individual Differences,” Behavioural Processes, 94 (March), 99–108.

[5]. Sherman, Gary D., Jonathan Haidt, Ravi Iyer, and James A. Coan (2013), “Individual Differences in the Physical Embodiment of Care: Prosaically Oriented Women Respond to Cuteness by Becoming More Physically Careful,” Emotion, 13 (1), 151–58.

[6]. Crilly, N., Moultrie, J., & Clarkson, P. J. (2004). Seeing things: consumer response to the visual domain in product design. Design studies, 25(6), 547-577.

[7]. Cavanaugh, L. A., Bettman, J. R., & Luce, M. F. (2015). Feeling love and doing more for distant others: Specific positive emotions differentially affect prosocial consumption. Journal of Marketing Research, 52(5), 657-673.

[8]. Lorenz, F. W. (1943). Fattening cockerels by stilbestrol administration. Poultry Science, 22(2), 190-191.

[9]. Schott, C., Neumann, O., Baertschi, M., & Ritz, A. (2019). Public service motivation, prosocial motivation and altruism: Towards disentanglement and conceptual clarity. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(14), 1200-1211.

[10]. Lorenz,Dijksterhuis, A., Smith, P. K., Van Baaren, R. B., & Wigboldus, D. H. (2005). The unconscious consumer: Effects of environment on consumer behavior. Journal of consumer psychology, 15(3), 193-202.

[11]. Shin, J., & Mattila, A. S. (2021). Aww effect: Engaging consumers in “non-cute” prosocial initiatives with cuteness. Journal of Business Research, 126, 209-220.

[12]. Isen, A. M. (1987). Positive affect, cognitive processes, and social behavior. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 20, pp. 203-253). Academic Press.

[13]. Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319(5870), 1687-1688.

[14]. Grant, A. M., & Berry, J. W. (2011). The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Academy of management journal, 54(1), 73-96.

[15]. Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. In White paper (pp. 1–39). Judd & Kenny MacKinnon. https://doi.org/978-1-60918-230-4

[16]. Shrout, P. E. & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422.