1. Introduction

Boom and busts are common in the economic cycle. From 2000 to 2024, the world economy undergoes countless expansions and recessions. Among them, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008 and the COVID-19 recently especially stand out for the huge undesirable effect on the world economy. In order to counter such economic shocks, macroeconomic control involving monetary and fiscal policies have played major roles. The macroeconomic regulation is significant because it regulates the direction and strength of the economy in a country, acting as an invisible hand. Although there are similarities in the macroeconomic policy regulations in both crises, it shows several differences in the implementation and effect of these policies due to the divergence in political, cultural, and economic circumstances in 2008 and 2020.

The most probable reason of the GFC was attributed to the subprime mortgage market in the US. Housing prices in the US were falling and an increasing number of borrowers could not repay loans. In essence, the crisis could be attributed to the sustainability of large global imbalances. This phenomenon was the outcome of long periods of extremely loose monetary policy in many advanced economies during the first decade after the millennium [1]. In order to combat the financial crisis, many countries used expansionary monetary policy to reduce interest rates close to 0. Central banks in the US and the UK switch to quantitative easing (QE) to sustain aggregate demand after quickly cutting short-term interest rates to effective lower bounds during the financial crisis in the 2008 [2]. However, at that time, money in the world economy was already contracting, and these QE programs did not lead to immediate money growth. The situation during the COVID-19 was different, after banking reforms, commercial banks held much higher levels of liquid assets and capital. The implementation of expansionary macroeconomic policies would be more effective. The shortage of monetary growth simply suggested that fiscal stimulus could not work. After the pandemic, however, there was a vigorous recovery in 2020 to 2021 due to the injection of substantial purchasing power into the US, the UK, and Euro zone economies in 2020 [3].

As discussed in the literature, the reasons behind each financial crisis were different, and the policy responses were slightly divergent. Subjecting to the political and economic background in 2008 and 2020, the effect of the macroeconomic regulation shows some differences as well. Taking China as an example, this paper compares the cause of the GFC and the COVID-19 shock, the macroeconomic policies’ responses to combating the recession, the effect of different policies, and lessons from both economic downturns.

2. Economic Impact of the GFC

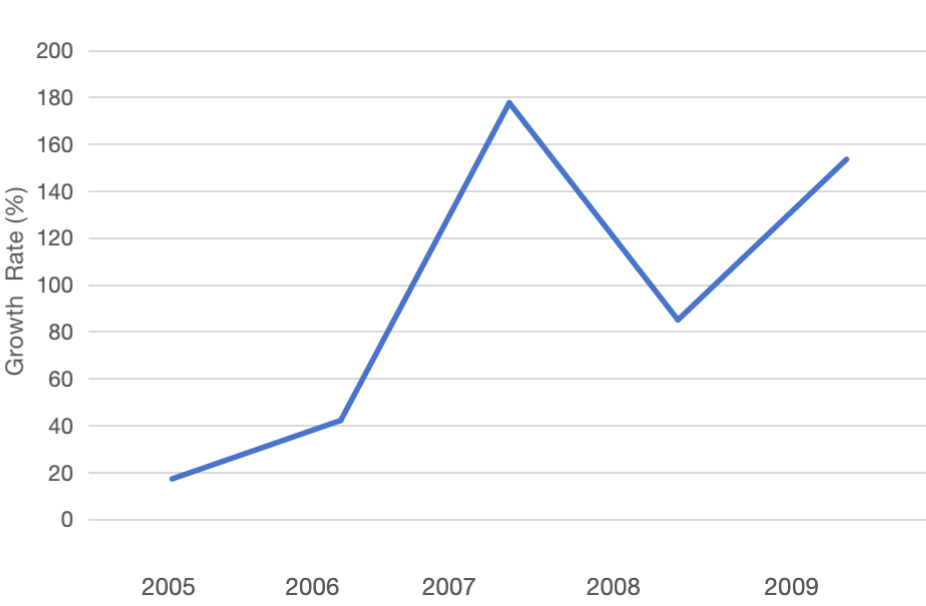

The GFC was one of the worst recessions in modern history. The crash of the US housing market and the subsequent failure of major financial institutions triggered the crisis. The three main reasons for the GFC were subprime mortgages with housing market speculation, the loose financial system regulation, and extreme risk-loving investors. The GFC had a major impact around the world, with many countries experiencing recessions that lasted for years. Businesses cut production and laid off workers. This had led to higher unemployment and lower consumer spending. With the increase in foreclosures, many people were losing their homes. This had a devastating impact on families and communities, with many struggling to make ends meet. As China's economy had become a major player, the downside of the GFC on China were considerably strong. The average increase in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2008 was significantly lower than that in 2007. The crisis spread through several channels. Starting in October 2007, the stock market in China collapsed, wiping out more than two-thirds of its market value. Figure 1 shows that the stock market total value dropped significantly in 2008. This circumstance also applied to the real estate market. A bubble started to grow with China’s booming economy [4].

Figure 1: Stock market total value traded to GDP for China.

In response to the challenge by the GFC, from the monetary side, the People’s Bank of China (PBC) loosened monetary policy by easing lending. The central bank targeted the total increase in bank loans at four trillion yuan. There was an extra 100 billion yuan allocated to policy banks. The broad money supply, M2, experienced a sharp increase of 27.7 percent, constituting 178 percent of GDP [5]. From the fiscal side, the four-trillion-yuan stimulus package could help China get rid of the trouble bring about by the GFC. The amount of the stimulus was huge, at 14 percent of GDP in 2008. In 2009, total government expenditure was 7.635 trillion yuan, up by 22.1 percent over the previous year and the total government deficit was the highest in six decades [6]. The expansionary fiscal and monetary policies managed to revive the economy from recession. However, China was already in a state of asset bubble before the four-trillion investment, and the plan continued to inject unlimited liquidity into the market, leading to further expansion of asset bubbles. The inflated land prices, housing prices, and commodity prices increased the production and manufacturing costs of Chinese enterprises, hurting the health of China’s real economy. In addition, China’s excessive production capacity was outdated and should have been abandoned. The four-trillion investment plan had further aggravated overcapacity, and enterprises have to produce even knowing that they are losing money. Such a stimulus package was a double-edged sword that needs further evaluation when used as a recovery tool for economic recession, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Economic Impact after the COVID-19 Pandemic

The GFC was a human social-economic shock as an internal product. On the contrary, the most significant feature of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 was the external impact on the human economy. It was not the product of the operation of human society, but the effect of the external natural environment on human society. The trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic was difficult to predict because it was caused by a new respiratory virus, which was poorly understood before the outbreak. Behind the COVID-19 shock, there were both the supply and demand shocks. The supply shock was primarily driven by the limitation of activities to control the spread of the virus [7]. Due to the high contagiousness of the virus, people were quarantined at home. Many businesses and factories were temporarily closed or unable to operate, resulting in a serious impact on the supply side. Problems in the supply of raw materials, along with the restricted mobility of human resources it led to a reduction in production. This supply shortfall had a negative effect on the economic recovery. After the supply shock, it came with the demand shock, that most people reduced their consumption as people took measures to avoid being infected by the virus, which resulted in a significant drop in demand side with a negative impact on economic growth.

The responses to the impact from the pandemic also involved fiscal and monetary policies in China. The PBC employed several expansionary monetary policies, including lowering the reserve requirement rate, loan prime rate (LPR), and re-lending and rediscount rates to cushion the economic blow of the pandemic. For the fiscal policy, the Chinese government enacted several tax relief measures, such as cutting the value-added tax, consumption tax, and corporate and individual income taxes [8]. The government also increased spending for new infrastructure construction. The Chinese government built “new” digital infrastructure across the country and the widely implemented the Internet of Things as policy responding to the COVID-19 shock [9]. With the use of proactive fiscal policy to provide funds for epidemic prevention and monetary policy to monetize fiscal deficit and stabilize financial markets, the Chinese economy gradually recovered.

4. Comparison and Discussion

4.1. Differences in Causes and Effects

The most apparent difference between the GFC and the COVID-19 shock is the cause of the recession. The GFC is an internal shock that is due to human intervention, but the COVID-19 shock is an external one that is hard to trace the origin. The GFC originated from the real estate bubble and the subprime crisis in the economic and financial system. It first affected the asset quality and cash flow of financial institutions, and the collapse and bankruptcy of financial institutions led to the credit crunch, which further affected the aggregate demand of society. The financial crisis spread from the virtual economy to the real economy, and the social supply capacity was not significantly damaged. In 2020, the COVID-19 epidemic first affected the supply capacity, and then affected the aggregate demand and financial system. The crisis spread from the real economy to the virtual economy. Supply chain shocks have affected industries such as automobiles and electronics.

All in all, internal shocks like GFC are the result of social and economic activities. Such shocks are detrimental to the society, but they are to some extent more predictable. External shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic shock is also harmful, but the extent of effect of external shocks on the economy as a whole is difficult to predict. The impact of the pandemic on China's economy is more complex, involving a public health crisis, a suspension of social-economic activities and industrial restructuring. The epidemic has caused a decrease in both demand and production, having a significant impact on consumption and investment. In the short term, China’s economy has been negatively affected, including a rising unemployment rate and a falling GDP growth rate. However, it has also encouraged China to speed up its industrial restructuring, transformation, and upgrading. The COVID-19 shock urged Chinese government to increase investment in education and medical insurance and develop new digital and online services to provide the foundation for economic recovery.

4.2. Policy Analysis and Implications

In response to the GFC, China followed the pace of many countries around the world to adopt expansionary policies, including four-trillion-yuan investment, industrial revitalization plans, and measures to stimulate consumption of automobiles, home appliances, and other measures. The four-trillion investment plan effectively increased output and promoted economic recovery and development in the short run. Before the crisis, the economy was assumed to be at an equilibrium state. The four-trillion plan was a strong expansionary fiscal policy, leading to an injection into the economy via government investment. In the Investment-Saving and Liquidity-Preference Money Supply (IS-LM) model, the expansionary fiscal policy would increase the investment and saving of the economy. Similarly, using the expansionary monetary policy with increased money supply, the central bank increased liquidity in the money market. Thus, the LM curve would also increase. At the new equilibrium, both output and interest rates would be higher than the original. In the short run, the expansionary fiscal policy can increase output at a constant price level. However, along with high output, high interest rates attracted capital flow into China, encouraging the expansion of asset market bubbles and stimulating the instability factors in China's monetary and financial system.

In the medium and long term, assuming that before the implementation of the four-trillion plan, the economy was located at the potential output level with the corresponding price level. In the Aggregate Supply-Aggregate Demand (AS-AD) model, the four-trillion investment and loose monetary policy both caused aggregate demand to rise. In the case of future economic expectations that the price would increase, it would then decrease the aggregate supply until reaching the original potential output. The new price level was higher than the initial price level. The growth rate of Consumer Price Index (CPI) increased from -1.6 in 2009 to 6.5 in 2011 due to the implementation of the expansionary policies [10]. The potential output would not increase due to the fact that expansionary fiscal policy cannot change the long-term economic growth rate. The output would return back to the potential output level and the price level would rise, increasing the inflationary pressure in China in the end.

The problem with the four-trillion investment is that the proportion of investment was mainly on the construction of railways, highways and other major infrastructure projects and the leveling-up of power grids, and the proportion in promoting people’s living standard was small. The government investment would lead to the crowding out effect, decreasing the savings rate. This would impede the accumulation of economic growth factors like human capital, contributing nearly nothing to the growth of GDP. The government deficit and inflation caused by huge government investment have a significant impact on the market economy system, and it took a long time for the market to absorb the negative impact. In short, the “four-trillion” plan allowed China to overcome the financial crisis in the short run rapidly. However, in the long term, it would not necessarily improve China's economic growth potential and national competitiveness, which was a shortsighted policy to save from the emergency. During the COVID-19 shock, the government did not use a stimulus method similar to the four-trillion yuan targeted on basic infrastructure because China's service industry contributed more than half of the economy. Consequently, after the epidemic, the government was more focused on the new technology and investment plan. The government had published venture plans for critical activities in 2020 with up to 33.8 trillion yuan. A “new foundation” is exceptionally outstanding in the plan. “New framework” is distinctive since it focuses on 5G foundation, Ultra High Voltage (UHV) power plant, intercity rapid rail line, metropolitan rail travel, and mechanical Internet [11]. The new foundation investment successfully helped China overcome the pandemic shock on the economy with an economic boost.

5. Conclusion

The GFC and the COVID-19 shock are both major crises that are detrimental to society and economies around the world. Although they are similar in effect and policy responses, there are some differences as well. The internal interactions among market participants ultimately created the GFC in 2008. That crisis was driven by deep weaknesses in the financial system that were hard to see at the time. The COVID-19 crisis was an exogenous economic shock. The essence of the COVID-19 shock lay not in the financial sector but in the real economy, where services and businesses had been closed, and incomes were shrinking. The Chinese government proposed the four-trillion plan to combat the GFC. Since 2008, central banks have continued to provide large amounts of liquidity and have kept interest rates low hoping to stimulate the economy. The side effect of these policies was that the private sector was heavily in debt and significantly more vulnerable to demand-side shocks from the coronavirus. In current circumstances, the government should employ moderate fiscal and monetary policies as the economy is gradually stepping out of the damage due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Chinese government should be more focused on technological advancement to increase its competitiveness.

The research primarily concentrated on the cause and effect along with policy analysis on the comparison between the GFC and the COVID-19 shock. The limitation is that the study only focuses on the policies and implications in China. It cannot be generalized to other countries around the world. Further research still needs to be done to analyze the effects and policies in other countries.

References

[1]. Mohan, R. (2009) Global financial crisis: Causes, impact, policy responses and lessons. Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, 879-904.

[2]. Ashworth, J. (2016). Quantitative easing by the major western central banks during the global financial crisis. In Banking Crises: Perspectives from The New Palgrave Dictionary. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK,251-270.

[3]. Greenwood, J. and Burton, A. (2020) Covid-19 pandemic recession–comparison with the GFC and Great Depression. Invesco.

[4]. Li, L., Willett, T. D. and Zhang, N. (2012) The Effects of the Global Financial Crisis on China′ s Financial Market and Macroeconomy. Economics Research International, 2012(1), 961694.

[5]. Han, M. (2013) The People's Bank of China during the global financial crisis: policy responses and beyond. In China's Economic Dynamics Routledge, 97-125.

[6]. Yu, Y. (2011) China’s policy responses to the global financial crisis. In the Impact of the Economic Crisis on East Asia. Edward Elgar Publishing.

[7]. Yeyati, E. L. and Filippini, F. (2021) Social and economic impact of COVID-19. Brookings Institution.

[8]. Zhao, B. (2020) COVID-19 pandemic, health risks, and economic consequences: Evidence from China. China Economic Review, 64, 101561.

[9]. Huang, Y., Qiu, H. and Wang, J. Y. (2021) Digital technology and economic impacts of COVID-19: Experiences of the People's Republic of China, ADBI Working Paper, No. 1276.

[10]. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Consumer Price Indices (CPIs, HICPs), COICOP 1999: Consumer Price Index: Total for China. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved from: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPALTT01CNM659N

[11]. Habibi, Z., Habibi, H. and Mohammadi, M. A. (2022) The potential impact of COVID-19 on the Chinese GDP, trade, and economy. Economies, 10(4), 73.

Cite this article

Li,C. (2024). The Comparative Analysis on the Impact of the Great Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 Shock in Response to Macroeconomic Policies. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,127,11-16.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICFTBA 2024 Workshop: Finance in the Age of Environmental Risks and Sustainability

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Mohan, R. (2009) Global financial crisis: Causes, impact, policy responses and lessons. Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, 879-904.

[2]. Ashworth, J. (2016). Quantitative easing by the major western central banks during the global financial crisis. In Banking Crises: Perspectives from The New Palgrave Dictionary. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK,251-270.

[3]. Greenwood, J. and Burton, A. (2020) Covid-19 pandemic recession–comparison with the GFC and Great Depression. Invesco.

[4]. Li, L., Willett, T. D. and Zhang, N. (2012) The Effects of the Global Financial Crisis on China′ s Financial Market and Macroeconomy. Economics Research International, 2012(1), 961694.

[5]. Han, M. (2013) The People's Bank of China during the global financial crisis: policy responses and beyond. In China's Economic Dynamics Routledge, 97-125.

[6]. Yu, Y. (2011) China’s policy responses to the global financial crisis. In the Impact of the Economic Crisis on East Asia. Edward Elgar Publishing.

[7]. Yeyati, E. L. and Filippini, F. (2021) Social and economic impact of COVID-19. Brookings Institution.

[8]. Zhao, B. (2020) COVID-19 pandemic, health risks, and economic consequences: Evidence from China. China Economic Review, 64, 101561.

[9]. Huang, Y., Qiu, H. and Wang, J. Y. (2021) Digital technology and economic impacts of COVID-19: Experiences of the People's Republic of China, ADBI Working Paper, No. 1276.

[10]. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Consumer Price Indices (CPIs, HICPs), COICOP 1999: Consumer Price Index: Total for China. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved from: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPALTT01CNM659N

[11]. Habibi, Z., Habibi, H. and Mohammadi, M. A. (2022) The potential impact of COVID-19 on the Chinese GDP, trade, and economy. Economies, 10(4), 73.