1. Introduction

Human capital is considered one of the most dynamic assets for the growth and development of any organization [1]. It has a critical role in driving economic growth, enhancing companies’ overall productivity, and propelling innovation of products. Job happiness is essential for employees. By improving job happiness, employees can increase productivity, improve well-being, and help make a positive organization culture.

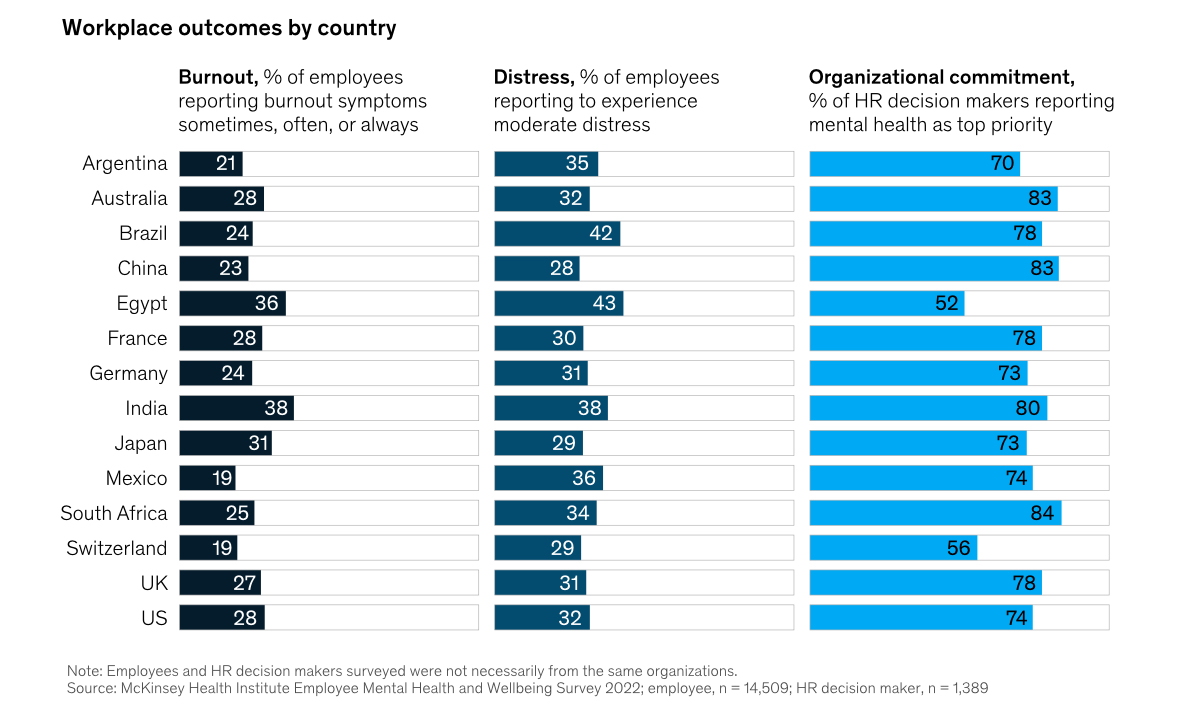

According to a study from McKinsey Health Institute, the highest and lowest job happiness index around the world is both found in Asian countries. This survey, conducted across 30 countries and involving over 30,000 employees to assess their physical, mental, social, and spiritual well-being. In Asia, the highest job happiness index is found in Turkey, with India and China ranking second and third, respectively. Japan, however, has the lowest index. As showing in Figure 1, workers from all over the world were asked if they felt exhausted, 22% of respondents reported that they had experienced job burnout. India led the world with 59% of respondents reporting burnout, while Singapore had 29% of respondents reporting burnout [2].

Figure 1: The rate of burnout and distress of employees from all over the world [2].

The data reveals significant differences in job happiness among Asian countries, despite their geographic proximity. Why does job happiness show such a great difference between neighboring countries in Asia? What factors play a role in job happiness?

By exploring those questions, this paper will help people have a better understanding of job happiness. The significance of studying job happiness is its profound impact on both employees and organizations. This paper will uncover insights into how job happiness influences employee productivity and job satisfaction. Moreover, this paper will explore what factors play a role in job happiness. Finally, this paper will give strategies to create a more supportive and fulfilling work environment for employees, leading to employees’ better mental and physical health. From a organization’s point of view, understanding how job happiness work and introducing policies to enhance employees’ job happiness can increase its overall performance, innovation, and competitive advantage in the market. As a result, job happiness is important to employees themselves and companies in the long run.

2. Literature Review

Wu et al. found that the positive emotional experience (job engagement) and cognitive evaluation (job satisfaction) of occupational well-being (job engagement, job burnout, turnover intention and job satisfaction) have a gain spiral process. They looked at ways to improve employee happiness at work and emphasized the use of psychological capital theory. Psychological capital theory not only focuses on the competitive advantage of the organization and employee performance, but also emphasizes the growth and development of employees, which opens up a new perspective for the study of employee career happiness [3].

Unggul Kustiawan et al. introduced several important factors that affect job happiness. Workers' job happiness is shaped by factors such as affective organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and employee engagement. Likewise, job performance is affected by job satisfaction, employee engagement, and the level of job happiness. Consequently, it is crucial for organizations, particularly those in the manufacturing sector, to consistently evaluate these factors during policymaking. Additionally, companies should regularly provide facilities and resources that support the improvement of employee conditions to ensure that job satisfaction and job happiness are well-maintained, thereby sustaining employee performance [4].

In research conducted by Waleed Al-Ali and colleagues, the team investigated the mediating effect of job happiness on the relationship between job satisfaction, employee performance, and turnover intentions within the UAE's oil and gas industry. The study, which randomly sampled 722 employees, found that job satisfaction significantly enhances employee performance, though it has a negligible impact on turnover intentions. Moreover, job happiness was found to have a direct and significant influence on both employee job performance and turnover intentions [1].Prior research endeavored to examine factors influencing job happiness and focus on the job happiness of a group of employees in certain fields. However, study on the differences of employees’ job happiness among Asian countries remains lacking. Therefore, this study attempts to examine the factors that influence the differences of employees’ job happiness among Asian countries to fill up the research gap. First, this paper will introduce the status of differences in job happiness among Asian countries. Next, case study will be given to examine the factors influencing job happiness. And then, this paper will explore the job performance of employees with high or low job happiness. Finally, this study will give the significance of job happiness and advice to improve employees’ job happiness among Asian countries.

In the fast-paced, rapidly evolving and competitive global business environment, both companies and employees are under unprecedented pressure. Especially following the pandemic, employees face not only health-related anxieties but also increased workloads and job uncertainty. The impact of these stressors is particularly evident in Asia, where burnout rates exceed the global average.

A recent report from insurance broker Aon and TELUS Health indicates that 35% of employees in Asia are at high risk for mental health problems, with another 47% being at moderate risk. The report also notes that 45% of Asian employees feel that their mental health is negatively affecting their workplace productivity, with significant losses reported in seven regions, including Malaysia, India, and the Philippines. Furthermore, the findings indicate that Asia faces a greater threat of workplace inefficiency, anxiety, and depression compared to other regions globally [5].

Starting on December 1, 2024, Singapore will introduce a comprehensive set of guidelines focused on flexible working arrangements. These guidelines will include the option for employees to work a four-day week, positioning Singapore to become the first country in Asia to adopt a four-day workweek at a national level. However, in the rest of Asia, most countries still strictly adhere to five-day workweek. Besides, overtime work culture is prevalent in Asian countries. In China, for instance, the phenomenon of overtime work is widespread, whether it is on mental or manual workers. 69.95% of the workers worked more than the 44 hours stipulated by the national law, and 25.24% worked 70 hours or more. Among them, manual laborers work overtime more seriously [6].

Overall, Asia is at a significantly greater risk for low work productivity, anxiety, and depression compared to other parts of the world, highlighting growing concerns about workplace well-being in the region. For example, Asia's work productivity score stands at 47.2 out of 100, which is considerably lower than the 66.7 in the U.S. and 60.1 in Europe [5].

3. Analysis

In this part, this paper will examine several factors of job happiness and find problems in real life situations.

3.1. Influence Factors

In the following text, this paper will explore three factors influencing job happiness.

3.1.1. Working Time

Research consistently shows that working time has a significant negative effect on workers' physical and mental health [7]. Physically, longer working hours reduce the time available for leisure and relaxation, which hinders the recovery of workers' energy and increases the risk of health issues such as hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and digestive disorders [8]. Additionally, extended working hours contribute to heightened mental stress, which can lead to unhealthy behaviors like excessive smoking, alcohol consumption, lack of exercise, obesity, and sleep deprivation [9]. Mentally, the increase in working hours results in greater fatigue and depletion of workers' resources, negatively impacting their overall well-being. And the increase of job burnout, which will lead to the decline of mental health, subjective well-being and job satisfaction [7]. At the same time, the increase in working hours reduces the leisure time of workers, aggravates the conflict between work and life, and increases work pressure, which in turn causes workers to have negative and even anxious emotions [10].

Take China as an example. Based on the 2016 China Family Panel Study (CFPS) data, research applies the ordered logistic regression method to analyze the impact of working hours on the physical and mental health of different types of workers and uses the Shapley value regression equation decomposition method to calculate the contribution degree of different working hours intervals to the health of workers. The study concludes as follows: First, excessive work hours are widespread among both intellectual and manual workers in China. The statistical results show that 69.95% of workers have working hours exceeding the national legal limit of 44 hours, and 25.24% of workers have working hours of 70 hours or more. Of these, manual workers have more serious excessive work hours. Second, working hours have a significant negative impact on the physical and mental health of workers. The regression results show that as working hours increase, the physical and mental health of both intellectual and manual workers deteriorates significantly. Of these, the impact of working hours on the physical health of intellectual workers is greater than that of manual workers. Third, there is a threshold effect of working hours on the physical and mental health of workers. When the weekly working hours of intellectual workers exceed 40 hours, and the weekly working hours of manual workers reach or exceed 50 hours, the health of workers begins to deteriorate. Working more than 70 hours per week, whether mentally or physically demanding, significantly worsens the mental and physical health of individuals [6].

Moreover, the research findings of the World Health Organization for 194 countries and regions also show that compared with workers who work 35-40 hours per week, those who work 55 hours or more per week have a higher risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke [11].

To sum up, working time has a significantly negative relationship with job happiness, influencing employees’ physical health, working load, and mental health.

3.1.2. Working Pressure

Malik & Noreen conducted research on teachers and discovered that organizational support mediates the impact of occupational stress on their affective well-being. The study employed Hierarchical Multiple Regression to investigate how perceived organizational support moderates the relationship between occupational stress and affective well-being. Initially, the analysis included occupational stress and perceived organizational support. In the subsequent step, the interaction between these variables was added, which significantly increased the explained variance in anxiety sensitivity, with a ∆R² value of .068, accounting for 6.8% of the variance in the dependent variable. The findings indicate that the interaction between occupational stress and perceived organizational support significantly influences affective well-being (β = -1.49, *p < .05). This underscores the essential moderating role of perceived organizational support in the relationship between occupational stress and affective well-being [12].

Another study conducted by Shen Yi and Zhou Zhen on Chinese employees explains the mediating mechanism of Chinese managers' work pressure on job satisfaction and verifies that work pressure has a significant negative impact on job satisfaction [13].

3.1.3. Supportive Human Resource

Supportive human resource management emphasizes providing "support" to employees, which includes offering emotional support (such as showing care, respect, listening, and making employees feel valued) as well as practical support (such as providing information, resources, tools, equipment, and trainings) [14]. These supports are an important signal that organizations are actively demonstrating their commitment to employees and value their contributions. Based on the reciprocity principle of social exchange theory, employees who receive support from their organization are likely to develop a stronger sense of identification with the organization, with this sense of connection being directly influenced by the amount of support they perceive. Proactive measures taken by the organization towards employees through supportive human resource management will be perceived by employees as valuing and respecting themselves [15], and employees will strengthen their identification with the organization when they feel respected [16].

A study conducted by Chen Jianan et al. shows that, based on the paired survey data of 347 employees from 71 enterprises, the impact of supportive human resource management on collective and individual work happiness. The results of this study show that supportive human resource management has a significant positive impact on collective and individual work happiness; Supportive human resources influence collective happiness at work by helping employees improve their sense of ownership. And by enhancing employee identity and self-efficacy affect job happiness [17].

3.2. Problem Analysis

In this part, this paper will propose problems of introducing job happiness in real life situations.

First of all, some scholars believe that the span of working time is an important factor affecting employees’ happiness. Increasing working hours will affect the psychological changes of employees [18] and physiological changes [19], which will further affect employees’ happiness negatively.

A study conducted through meta-analysis revealed that there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between work hours and job performance, encompassing both task performance and contextual performance [20]. Considering employee happiness, is the peak of the inverted U-shaped curve the best working hours most companies should promote? If not, what is a reasonable working time that takes both job happiness and job performance into account?

Resources that companies can provide to employees include training sessions like online courses and workshops, career counseling like mentorship programs, health insurance and mental health support, and etc. According to Chen Chunhua et al., job resources are an important variable to predict career happiness. Building a theoretical model of the internal mechanism of organizational support resources' impact on employee happiness, they empirically analyzed the positive impact of organizational support resources on employee happiness [21].

However, resources in an organization are scarce, which means not every employee can get resources equally. In this way, it might be difficult to organization allocate resources to improve overall job happiness to the maximum extent.

Researchers have found that job happiness is affected by individual factors. Age and work motivation are the two variables that are closely related to career happiness. In terms of age, Peter Warr investigated 1,686 employees and found that there was a U-shaped relationship between employee age and career happiness [22]. He showed that the happiness of middle-aged people was lower than that of young people and old people.

In terms of work motivation, Zheng Nan and Zhou Enyi took 912 grassroots civil servants in Shaanxi Province as research objects and found that there was a significant positive correlation between public service motivation and career happiness of grassroots civil servants [23].

4. Suggestions

The solution to the problem of balancing both job happiness and job performance will be changing the working time flexibly based on each company’s real situation. For example, if employees already feel very stressful and overwhelmed in a certain period, the working time should be shorten based on this situation. Bakker et al. studied the impact mechanism of job characteristics (job demand and job resources) on individual job happiness and concluded that job demand and career happiness were significantly negatively correlated [24]. When the demand for work increases, workers' energy consumption increases, and people's health, job satisfaction, and work motivation decline. Therefore, job demands have a negative effect on occupational happiness.

In this way, there is no exact working time that is suitable for every company. A company should change the working time positively and flexibly, which means it should investigate employees' work intensity and conditions regularly, paying attention to employees' mental health and job happiness.

The solution to the problem of allocating resources to maximize overall job happiness would be set a reasonable way of resource allocation and give all employees equal opportunities to get more work resources. The optimal approach is to encourage a balance between individual competition and group collaboration. Luft proposes that the rewards, whether monetary, psychological, or both, that individuals earn for a certain level of performance are influenced by the performance of their peers as well as their own efforts. However, an individual’s performance is generally independent of the actions of their peers [25]. By both considering an employee’s performance in both individual work and group corporation, managers can better assess an employee’s job ability, and allocate resources in a more comprehensive way.

Also, company promotions should be transparent and open to all employees. Cassar & Buttigieg found that organizational justice has a positive impact on employee happiness [26]. Moreover, Zheng Xiaoming and Liu Xin investigated 199 employees of a Chinese enterprise by using multi-time-point matching questionnaire [27]. Furthermore, it is found that there is a significant positive correlation between interactive justice and employee happiness in organizational justice. In this way, companies should supervise corruption strictly and give employees motivation to have a better performance.

Research on areas such as self-determined behavior, emotional intelligence, and work innovation converges on the idea of a virtuous organization. These organizations are characterized by cultures grounded in strong ethical and moral principles, with leaders who inspire the best in their employees. Virtuous organizations aim to achieve success by doing good, aligning their actions with ethical values. They focus on multiple bottom lines, not just economic outcomes, effectively integrating economic growth with the development of their people.

Employees under this environment will find their values and motivation more easily and quickly. As a result, because of the virtuous organizations cultures, they will apply more concepts related to positive psychology to their workplaces. Therefore, although factors like age may influence employees to some degree, employees still can find strong motivation and impulse to finish their job with passion if organizations provide a kind and moral environment for employees to work.

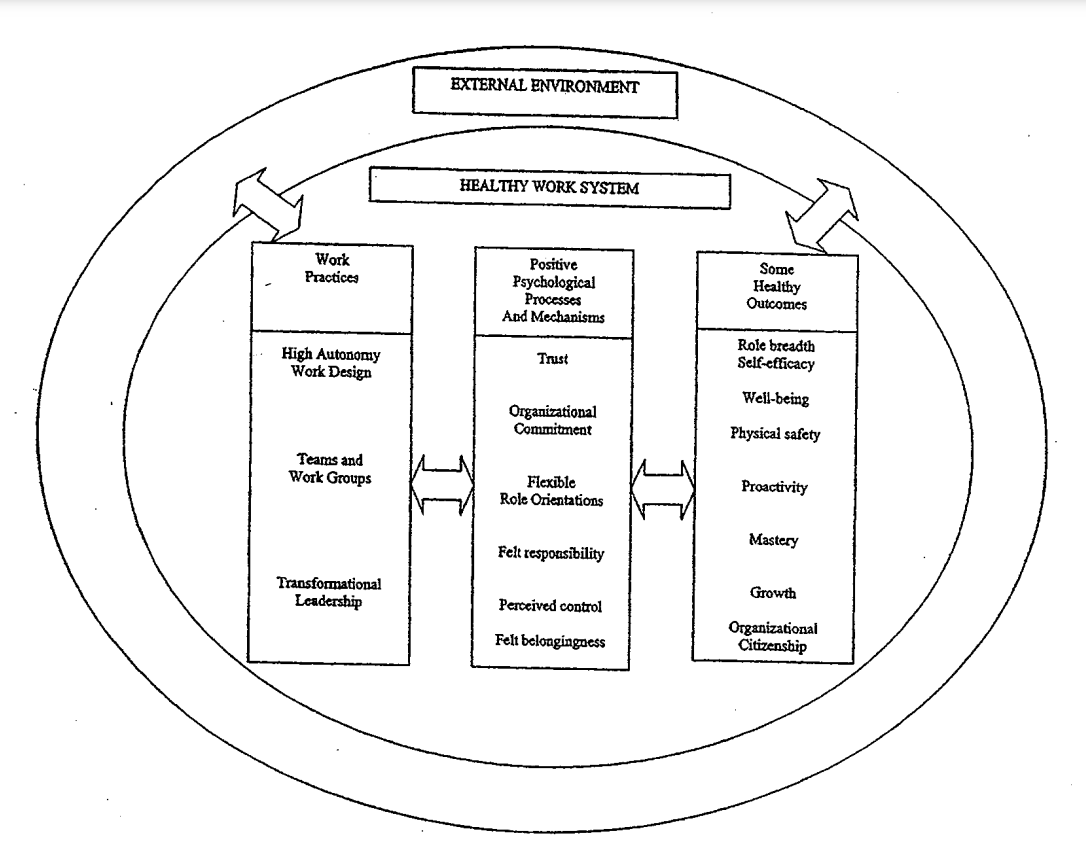

As showing in Figure 2, it presents essential for employees to have appropriate demands, as well as a suitable collective goal. Researchers have used the demand/control model to design jobs that increase psychological and physical well-being [28]. According to this model, healthy work environments are built by appropriate demands like suitable group production goals, trust, and healthy outcomes produced in a group.

Figure 2: A healthy work system [28].

Therefore, organizations should set a periodical group goal regularly, uniting employees to work hard for achieving a common goal. For employees, it is important to have suitable demands for their own work, and find motivation and values in their everyday work [29, 30].

5. Conclusion

This paper examines several factors of job happiness, finding problems and giving suggestions to organizations for increasing overall job happiness in the real-life situations. First, working time has a negative relationship with job happiness. Similarly, working pressure also has a negative impact on job happiness. Exceed working pressure may let employees feel overwhelmed, decreasing their job happiness. By contrast, supportive human resources will increase job happiness by enhancing employees’ identity and self-efficacy. Next, the apparent problems include balance between job happiness and job performance, allocation of resources and the methods of finding job happiness. To solve the problem of finding a balance between job happiness and job performance, this paper suggests companies to investigate employees regularly to set the most reasonable working time and justifies that there is no universal working time for every company. To allocate resources with an organization better, this paper suggests organizations to assess employees both individually and collectively. To help employees have more strong motivation, this paper suggests organizations to construct a virtuous and moral culture for employees to study. Also, employees should have appropriate demands and collective goals to work for. This paper aims to help employees self-actualize and have a stronger motivation to work. At the same time, this paper hopes that suggestions can help improve overall job happiness of organizations, improve the quality of human resources, and promote the long-term development of the industry. However, this paper still has some limitations to further consider. First, most data this paper uses are from case study rather than generic data, which means situations this paper discusses and suggestions it gives should be further justify. Second, because the difference of cultural soil, suggestions in this paper may be limited to Asia, while not apply to Europe or America. For future study, samplings and data can be examined through surveys and interviews rather than previous study. In this way, the value of samplings and data will more comply to nowadays trends and situations, and primary data can be discussed. Second, to explore job happiness in a broader scope, future study can use global data to study the situation in Europe and America also and give a more comprehensive solution adapt to global conditions.

References

[1]. Al-Ali, W., Ameen, A., Isaac, O., Khalifa, G. S., & Shibami, A. H. (2019). The mediating effect of job happiness on the relationship between job satisfaction and employee performance and turnover intentions: A case study on the oil and gas industry in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research, 13(4).

[2]. Brassey, J., Coe, E., Dewhurst, M., Enomoto, K., Giarola, R., Herbig, B., & Jeffery, B. (2022, May). Addressing employee burnout: Are you solving the right problem? McKinsey Health Institute. https://www.mckinsey.com.cn

[3]. Wu, W.-J., Liu, Y., Lu, H., & Xie, X.-X. (2012). The Chinese indigenous psychological capital and career well-being. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 44(10), 1349-1370.

[4]. Kustiawan, U., Marpaung, P. A. R. D. A. M. E. A. N., Lestari, U. D., & Andiyana, E. (2022). The effect of affective organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and employee engagement on job happiness and job performance in manufacturing companies in Indonesia. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, 19(52), 573-591.

[5]. Goh, C. T. (2023, September 19). 4 in 5 employees in Asia have moderate to high mental health risk, study shows. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com

[6]. Wang, G., & Su, Y. (2021). Threshold effect of working hours on health. Studies in Labor Economics, 4, 81-98.

[7]. Friedland, D., & Price, R. (2003). Underemployment: Consequences for the health and well-being of workers. American Journal of Community Psychology, 32(1-2), 33-45.

[8]. Sparks, K., Cooper, C., Fried, Y., & Shirom, A. (1997). The effects of hours of work on health: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70(4), 391-408.

[9]. Taris, T., Kompier, M., Geurts, S., Houtman, I., & van den Heuvel, F. (2010). Professional efficacy, exhaustion, and work characteristics among police officers: A longitudinal test of the learning-related predictions of the demand-control model. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(2), 455-474.

[10]. Unger, D., Niessen, C., Sonnentag, S., & Neff, A. (2014). A question of time: Daily time allocation between work and private life. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(1), 158-176.

[11]. Pega, F., Nafrádi, B., Momen, N., Ujita, Y., Streicher, K., Prüss-üstün, A., Technical Advisory Group, Descatha, A., Driscoll, T., Fischer, F., Godderis, L., Kiiver, H., Li, J., Hanson, L., Rugulies, R., Sprensen, K., & Woodruff, T. (2021). Global, regional, and national burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours for 194 countries, 2000-2016: A systematic analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environment International, 154, 106595.

[12]. Malik, S., & Noreen, S. (2015). Perceived organizational support as a moderator of affective well-being and occupational stress among teachers. Pakistan Journal of Commerce & Social Sciences, 9, 865-874.

[13]. Shen, Y., & Zhou, Z. (2016). The work stress and occupational well-being of managers: The role of self-efficacy and recovery experiences. Nanjing Social Sciences, (9), 24-30.

[14]. Allen, D. G., Shore, L. M., & Griffeth, R. W. (2003). The role of perceived organizational support and supportive human resource practices in the turnover process. Journal of Management, 29(1), 99-118.

[15]. Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., & Liden, R. C. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 40(1), 82-111.

[16]. Tsai, C. H. (2013). Mediating impact of social capital on the relationship between perceived organizational support and employee well-being. Journal of Applied Sciences, 13(21), 4726-4731.

[17]. Chen, J., Chen, M., & Jin, J. (2018). Supportive human resource management and employee work well-being: An empirical study based on the mediation mechanism. Frontiers of Economics in China, 13(1), 137-164. https://doi.org/10.16538/j.cnki.fem.2018.01.006.

[18]. Adkins, C. L., & Premeaux, S. F. (2012). Spending time: The impact of hours worked on work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 380-389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.09.003

[19]. Rudolf, R. (2014). Work shorter, be happier? Longitudinal evidence from the Korean five-day working policy. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 1139-1163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9468-1

[20]. Song, H., Gao, R., Zhang, Q., & Cheng, Y. (2022). Nonlinear relationship between working hours and job performance: A meta-analysis. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(12), 2666.

[21]. Chen, C., Song, Y., & Cao, Z. (2014). The internal mechanism of organizational support resources influencing employee well-being: A case study based on Visionary Technology. Journal of Management, 11(2), 206-214.

[22]. Warr, P. (1992). Age and occupational well-being. Psychology and Aging, 7, 37-45. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.7.1.37

[23]. Zheng, N., & Zhou, E. (2017). An empirical study on the impact of public service motivation on occupational well-being of grassroots civil servants in China. Chinese Public Administration, (3), 83-87.

[24]. Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD-R approach. The Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 389-411.

[25]. Luft, J. (2016). Cooperation and competition among employees: Experimental evidence on the role of management control systems.

[26]. https://s100.copyright.com/AppDispatchServlet?publisherName=ELS&contentID=S1044500516000214&orderBeanReset=true

[27]. Cassar, V., & Buttigieg, S. C. (2015). Psychological contract breach, organizational justice and emotional well-being. Personnel Review, 44, 217-235.

[28]. DeJoy, D. M., Wilson, M. G., Vandenberg, R. J., McGrath‐Higgins, A. L., & Griffin‐Blake, C. S. (2010). Assessing the impact of healthy work organization intervention. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(1), 139-165.

[29]. Zheng, X., & Liu, X. (2016). The impact of interactional fairness on employee well-being: The mediating role of psychological empowerment and the moderating role of power distance. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 48(6), 693-709.

[30]. Karasek, R. A., & Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. New York: Basic Books.This list incorporates the numbering format as requested and includes translations for the Chinese references.

Cite this article

Wu,Q. (2024). Exploring Job Happiness Across Asian Countries: Factors, Challenges, and Strategies for Enhancing Employee Well-being and Organizational Performance. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,113,45-53.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICFTBA 2024 Workshop: Human Capital Management in a Post-Covid World: Emerging Trends and Workplace Strategies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Al-Ali, W., Ameen, A., Isaac, O., Khalifa, G. S., & Shibami, A. H. (2019). The mediating effect of job happiness on the relationship between job satisfaction and employee performance and turnover intentions: A case study on the oil and gas industry in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research, 13(4).

[2]. Brassey, J., Coe, E., Dewhurst, M., Enomoto, K., Giarola, R., Herbig, B., & Jeffery, B. (2022, May). Addressing employee burnout: Are you solving the right problem? McKinsey Health Institute. https://www.mckinsey.com.cn

[3]. Wu, W.-J., Liu, Y., Lu, H., & Xie, X.-X. (2012). The Chinese indigenous psychological capital and career well-being. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 44(10), 1349-1370.

[4]. Kustiawan, U., Marpaung, P. A. R. D. A. M. E. A. N., Lestari, U. D., & Andiyana, E. (2022). The effect of affective organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and employee engagement on job happiness and job performance in manufacturing companies in Indonesia. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, 19(52), 573-591.

[5]. Goh, C. T. (2023, September 19). 4 in 5 employees in Asia have moderate to high mental health risk, study shows. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com

[6]. Wang, G., & Su, Y. (2021). Threshold effect of working hours on health. Studies in Labor Economics, 4, 81-98.

[7]. Friedland, D., & Price, R. (2003). Underemployment: Consequences for the health and well-being of workers. American Journal of Community Psychology, 32(1-2), 33-45.

[8]. Sparks, K., Cooper, C., Fried, Y., & Shirom, A. (1997). The effects of hours of work on health: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70(4), 391-408.

[9]. Taris, T., Kompier, M., Geurts, S., Houtman, I., & van den Heuvel, F. (2010). Professional efficacy, exhaustion, and work characteristics among police officers: A longitudinal test of the learning-related predictions of the demand-control model. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(2), 455-474.

[10]. Unger, D., Niessen, C., Sonnentag, S., & Neff, A. (2014). A question of time: Daily time allocation between work and private life. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(1), 158-176.

[11]. Pega, F., Nafrádi, B., Momen, N., Ujita, Y., Streicher, K., Prüss-üstün, A., Technical Advisory Group, Descatha, A., Driscoll, T., Fischer, F., Godderis, L., Kiiver, H., Li, J., Hanson, L., Rugulies, R., Sprensen, K., & Woodruff, T. (2021). Global, regional, and national burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours for 194 countries, 2000-2016: A systematic analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environment International, 154, 106595.

[12]. Malik, S., & Noreen, S. (2015). Perceived organizational support as a moderator of affective well-being and occupational stress among teachers. Pakistan Journal of Commerce & Social Sciences, 9, 865-874.

[13]. Shen, Y., & Zhou, Z. (2016). The work stress and occupational well-being of managers: The role of self-efficacy and recovery experiences. Nanjing Social Sciences, (9), 24-30.

[14]. Allen, D. G., Shore, L. M., & Griffeth, R. W. (2003). The role of perceived organizational support and supportive human resource practices in the turnover process. Journal of Management, 29(1), 99-118.

[15]. Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., & Liden, R. C. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 40(1), 82-111.

[16]. Tsai, C. H. (2013). Mediating impact of social capital on the relationship between perceived organizational support and employee well-being. Journal of Applied Sciences, 13(21), 4726-4731.

[17]. Chen, J., Chen, M., & Jin, J. (2018). Supportive human resource management and employee work well-being: An empirical study based on the mediation mechanism. Frontiers of Economics in China, 13(1), 137-164. https://doi.org/10.16538/j.cnki.fem.2018.01.006.

[18]. Adkins, C. L., & Premeaux, S. F. (2012). Spending time: The impact of hours worked on work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 380-389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.09.003

[19]. Rudolf, R. (2014). Work shorter, be happier? Longitudinal evidence from the Korean five-day working policy. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 1139-1163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9468-1

[20]. Song, H., Gao, R., Zhang, Q., & Cheng, Y. (2022). Nonlinear relationship between working hours and job performance: A meta-analysis. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(12), 2666.

[21]. Chen, C., Song, Y., & Cao, Z. (2014). The internal mechanism of organizational support resources influencing employee well-being: A case study based on Visionary Technology. Journal of Management, 11(2), 206-214.

[22]. Warr, P. (1992). Age and occupational well-being. Psychology and Aging, 7, 37-45. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.7.1.37

[23]. Zheng, N., & Zhou, E. (2017). An empirical study on the impact of public service motivation on occupational well-being of grassroots civil servants in China. Chinese Public Administration, (3), 83-87.

[24]. Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD-R approach. The Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 389-411.

[25]. Luft, J. (2016). Cooperation and competition among employees: Experimental evidence on the role of management control systems.

[26]. https://s100.copyright.com/AppDispatchServlet?publisherName=ELS&contentID=S1044500516000214&orderBeanReset=true

[27]. Cassar, V., & Buttigieg, S. C. (2015). Psychological contract breach, organizational justice and emotional well-being. Personnel Review, 44, 217-235.

[28]. DeJoy, D. M., Wilson, M. G., Vandenberg, R. J., McGrath‐Higgins, A. L., & Griffin‐Blake, C. S. (2010). Assessing the impact of healthy work organization intervention. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(1), 139-165.

[29]. Zheng, X., & Liu, X. (2016). The impact of interactional fairness on employee well-being: The mediating role of psychological empowerment and the moderating role of power distance. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 48(6), 693-709.

[30]. Karasek, R. A., & Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. New York: Basic Books.This list incorporates the numbering format as requested and includes translations for the Chinese references.