1.Introduction

South Korea’s economic transformation is a remarkable story of rapid development, hence nicknamed the “Miracle on the Han River.” In the 1960s, South Korea had one of the worst economies in the world, with its economy heavily reliant on agriculture and foreign aid. However, through the government’s new policies and its famous Five-Year Plans, the country embarked on an aggressive path of industrialization and export-led growth. Key industries such as textiles, steel, shipbuilding, and electronics were developed, fueling economic growth and increasing the country’s global competitiveness [1].

After the Korean War (1950-1953), South Korea was left devastated, with much of its infrastructure destroyed and its economy in ruins. The country had a predominantly agrarian economy, characterized by low productivity, limited industrial capacity, and widespread poverty. In 1960, South Korea’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita was around 79 dollars, placing it among the least developed countries, as shown in the data from the World Bank [2].

By the 1980s and 1990s, South Korea had emerged as a major player in the global economy, with conglomerates like Samsung and Hyundai becoming household names worldwide. The 1996 entry into numerous global economic organizations signaled its recognition as a high-income country. In the early 2000s, South Korea had achieved significant economic milestones: a high GDP per capita, advanced technological infrastructure, and a strong middle class. These factors, combined with its resilience in overcoming economic challenges, confirmed that South Korea had indeed become a developed country by this period.

The challenges South Korea faced were daunting. The nation lacked natural resources, suffered from political instability, and was heavily reliant on foreign aid, particularly from the United States. The country was also burdened by high population growth, which strained its limited resources. Additionally, South Korea had to contend with a lack of technological expertise and industrial infrastructure.

In response to these challenges, the South Korean government, led by Park Chung-Hee, embarked on a series of five-year economic plans starting in 1962. These plans focused on industrialization, export-led growth, and the development of key industries. The government also invested heavily in education, recognizing the need to build a skilled workforce to support its industrial ambitions [3].

This development in less than half a century was one of the biggest success stories in the history of development. The policies that have been implemented have improved the country, thus, this article looks into these policies to understand how other countries can improve their own policy and politics.

2.Five-Year Plans

As discussed in the previous session, South Korea’s five-year economic plans were reforms that the government began to implement in 1962 and played a critical role in transforming the country from poor into a highly industrialized and developed nation. These plans were created by the then President of the country, Park Chung-Hee, and were designed to promote rapid industrialization, technological advancement, and export-led growth. Table 1 summarizes all Five-Year Plans.

Table 1: A brief overview of every Five-Year Plan.

|

Year |

Content |

Effect |

|

1962-1966 |

Industrialization of key industries |

Established basic structure and set stage for development |

|

1967-1971 |

Heavy and chemical industries; Improved infrastructure |

Shifted towards export economy |

|

1972-1976 |

Heavy industries and export |

Prepared the basis for long-term economic resilience |

|

1977-1981 |

Technological advancement and education |

Increased productivity |

|

1982-1986 |

Economic stabilization and social welfare |

Increased GDP and welfare |

The First Five-Year Plan (1962-1966) focused on laying the groundwork for industrialization by developing key industries such as textiles, cement, and fertilizer. It aimed to reduce dependence on foreign aid by fostering self-sustained economic growth. The plan was successful in establishing a basic industrial structure and setting the stage for future development [4].

Subsequent plans built on this foundation, with each focusing on different aspects of economic growth. The Second Five-Year Plan (1967-1971) dramatically altered South Korea’s development strategy with new policy towards chemical industries. This marked the beginning of South Korea’s shift towards becoming an export-oriented economy. The government also invested heavily in infrastructure, including transportation networks and power plants, which were essential for supporting industrial growth. The drive created positive effects in treated industries long after major elements of the policy were retrenched.

The Third and Fourth Five-Year Plans (1972-1981) continued to prioritize heavy industries and exports, with a significant focus on technological advancement and education. During this period, South Korea began to develop its electronics industry, which would later become a cornerstone of its economy. The government also promoted research and development, leading to innovations that enhanced productivity and competitiveness.

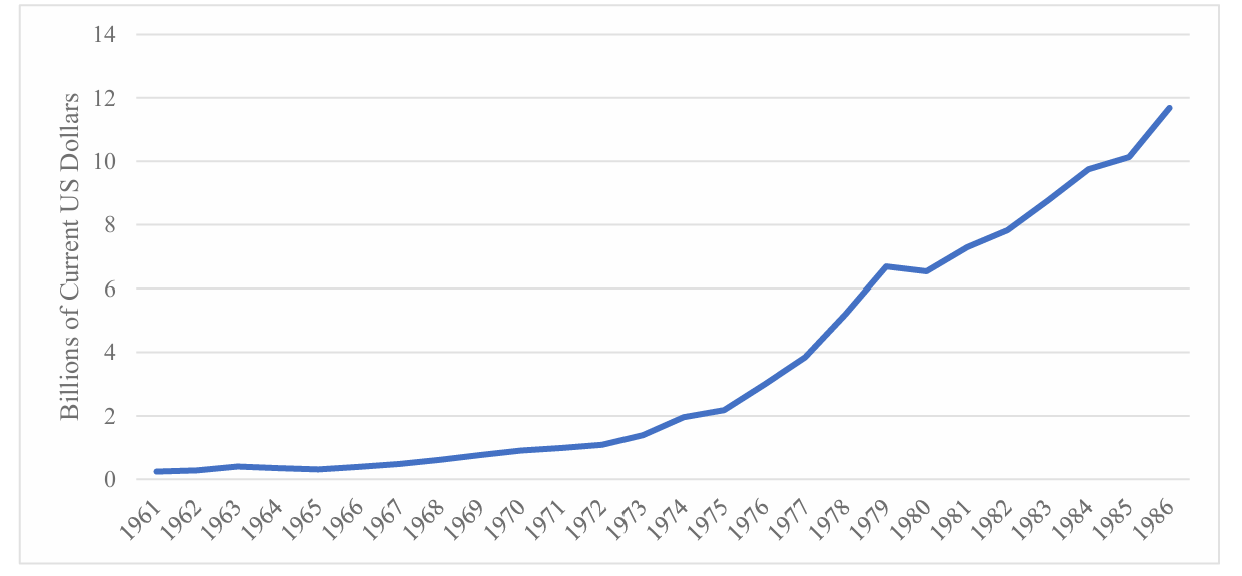

By the time the Fifth Five-Year Plan (1982-1986) was implemented, South Korea had established itself as a major player in the global economy. While the first four plans focused on rapid industrialization, export-led growth, and the development of heavy and chemical industries, the fifth plan aimed to stabilize the economy, reduce inflation, and improve social welfare. By emphasizing economic stabilization and enhancing living standards, the fifth plan ensured that the growth achieved in earlier decades was sustainable and inclusive. It helped South Korea transition from a rapidly growing industrial economy to a more mature and stable economic system, laying the groundwork for its eventual status as a developed country. These plans significantly improved living standards, reduced poverty, and created a skilled workforce. The plans also had a significant effect on the GDP of the country, where the GDP was 2.42 billion current day US dollars before the plans (1961), and increased to 101.3 billion after all five plans were implemented, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: GDP between 1961 and 1985 (Data Source: World Bank).

3.International Monetary Fund Bailout

While the Five-Year Plans set the road for South Korea’s economic success, the country soon faced new problems—the Asian Financial Crisis. A major international event that started from Japan and Thailand that spread to the entire continent, making South Korea one of the most hard-hit countries in this crisis. The Asian financial crisis was triggered by Japanese commercial banks. Their reduction of share in the Asian economy in response to caused troubles in Thailand and South Korea. When the Thai baht came under speculative pressure due to its overvaluation from a fixed exchange rate pegged to the US dollar, Thailand's economy, burdened by excessive foreign debt, became highly vulnerable. The Thai government's unsuccessful attempt to defend the baht led to its devaluation on July 2, 1997, triggering panic and a regional withdrawal of foreign investments [5].

South Korea was one of the hardest-hit countries during the Asian Financial Crisis. By late 1997, South Korea’s economy was in turmoil, with its currency, the won, losing over half its value against the US dollar. The crisis exposed the vulnerabilities of South Korea’s highly leveraged corporate sector, dominated by large conglomerates known as chaebols. These conglomerates had accumulated massive amounts of debt to finance their rapid expansion, much of it in foreign currencies. As the won depreciated, the cost of servicing this foreign debt skyrocketed, leading to widespread corporate insolvencies [6].

The crisis also revealed deep-seated weaknesses in South Korea’s banking sector. Banks had extended large amounts of credit to chaebols without proper risk assessment, leading to a sharp increase in non-performing loans. As corporate defaults rose, banks found themselves undercapitalized and unable to meet their obligations, leading to a liquidity crisis. In December 1997, South Korea was forced to seek help from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to stabilize its economy.

The IMF then provided 58 billion US dollars in worth of bailout support, used to stabilize the Korean won, which had depreciated sharply due to capital flight and loss of confidence in the economy. The infusion of foreign currency reserves helped to support the won, allowing the South Korean government to intervene in the foreign exchange market and prevent further devaluation. This stabilization of the currency was essential in curbing the spiraling inflation that had begun to take hold due to the falling won, thus preventing the crisis from worsening [7].

In addition to providing financial stability, the IMF package came with strict conditionality, requiring South Korea to implement a series of structural reforms aimed at addressing the root causes of the crisis. These reforms targeted the corporate sector, the banking system, and the labor market, and were designed to promote greater transparency, efficiency, and competitiveness in the economy.

4.Economic Reforms

4.1.Corporate Restructuring

One of the most significant reforms was the restructuring of South Korea’s large conglomerates, known as chaebols. Korean chaebols are powerful, family-controlled business groups that dominate South Korea’s economy. They own multiple companies across different industries, often linked through complex ownership structures. Chaebols, including modern companies such as Samsung and Hyundai, were key to South Korea’s rapid economic growth but have faced criticism for their monopolistic power and significant influence over government policies.

Before the crisis, these chaebols had accumulated massive amounts of debt through aggressive expansion, financed largely by short-term loans. This made them highly vulnerable to economic downturns and currency fluctuations. The IMF package required the South Korean government to enforce strict financial discipline on the chaebols, including reducing their debt-to-equity ratios, improving corporate governance, and increasing transparency in their financial operations [8].

The reform process involved the closure of insolvent companies, the reduction of cross-shareholding and mutual debt guarantees among chaebol subsidiaries, and the introduction of independent audits and stricter accounting standards. These measures helped to reduce the financial risks associated with the chaebols, leading to more sustainable corporate practices. Over time, this restructuring improved the financial health of South Korean businesses, making them more resilient to future economic shocks.

4.2.Banking Sector Reforms

The crisis exposed significant weaknesses in South Korea's banking sector, including poor risk management, inadequate capitalization, and a high proportion of non-performing loans. To address these issues, the IMF required South Korea to overhaul its financial system by closing down non-viable banks, recapitalizing viable ones, and improving regulatory oversight [9].

The government established the Korea Asset Management Corporation (KAMCO) to take over and dispose of non-performing loans, which helped to clean up the balance sheets of the banks. Additionally, the Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC) was created to enhance regulatory oversight and ensure the stability of the financial system. These reforms restored confidence in the banking sector, attracted foreign investment, and improved the overall efficiency of financial institutions. As a result, South Korea’s banking sector emerged stronger and more capable of supporting economic growth.

4.3.Labor Market Reforms

The IMF also pushed for labor market reforms to increase flexibility and competitiveness. Prior to the crisis, South Korea had a rigid labor market with strong job security protections, which made it difficult for companies to adjust their workforce in response to economic conditions. The IMF conditions included measures to increase labor market flexibility, such as easing restrictions on layoffs and promoting more flexible working arrangements [10].

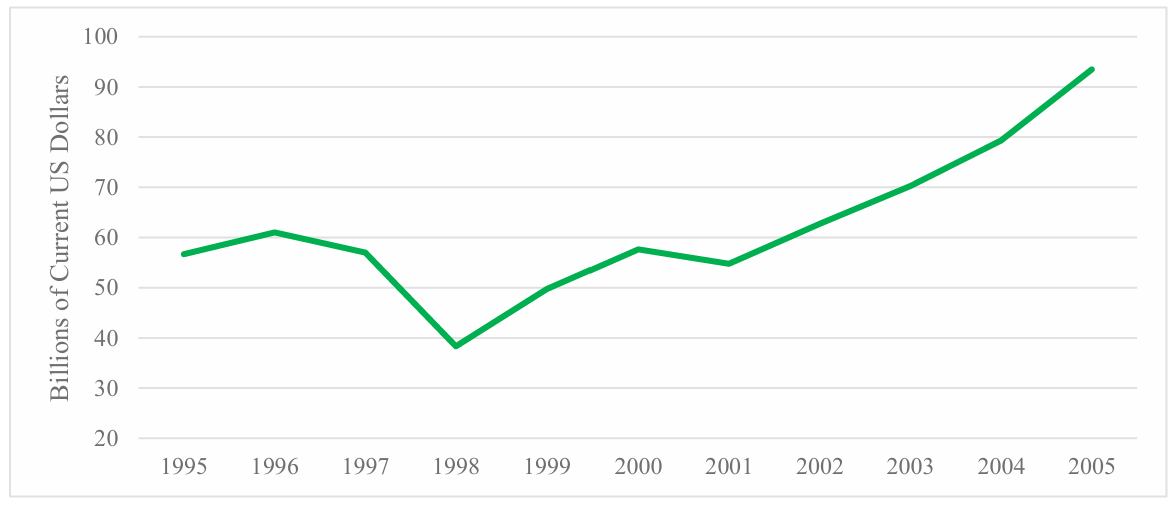

These reforms were controversial and met with resistance from labor unions, but they were crucial in allowing companies to restructure and adapt to the changing economic environment. Over time, the labor market reforms helped with reducing unemployment, increasing labor productivity, and making South Korean companies more competitive on the global stage. This increased flexibility also attracted foreign investment, as investors were more confident in the ability of South Korean businesses to adjust to market demands. In the years after the reforms, the country’s economy swiftly rebounded from the effects of the crisis, soon increasing its GDP to a historical high, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: GDP between 1995 and 2005 (Data Source: World Bank).

5.Discussion and Suggestions

The development of South Korea has been one of the biggest success stories in not only the modern, but the entire history of economic development. In just a few decades, South Korea’s economy changed from highly depending on agriculture to depending on exporting high-technology products such as cars, televisions, mobile phones or computers. To understand the effects of policies on the Korean economy, the policies can be analyzed from two different perspectives.

From a classical economics perspective, the combination of the IMF bailout and structural reforms in South Korea worked because they aligned with the principles of market efficiency, financial discipline, and minimal government intervention in the long term. The IMF's immediate injection of capital helped stabilize the currency and restore confidence, which, classical economists would argue is crucial for maintaining the free flow of capital and the functioning of markets. The structural reforms, particularly in the corporate and banking sectors, reduced inefficiencies by eliminating non-viable firms and cleaning up non-performing loans. This led to a more efficient allocation of resources, which classical economists believe is essential for long-term growth. By promoting transparency, improving corporate governance, and enhancing financial oversight, these reforms allowed market forces to operate more effectively, ultimately leading to a more stable and competitive economy [11].

From a Keynesian economics perspective, the IMF bailout and structural reforms in South Korea were effective because they addressed both demand-side and supply-side issues during the crisis. The Keynesian approach emphasizes the role of government intervention in stabilizing the economy during periods of crisis. The IMF's financial assistance provided the necessary liquidity to prevent a complete collapse in aggregate demand, which was critical in maintaining economic activity and preventing deeper recession. The structural reforms can be seen as supply-side interventions that improved productivity and efficiency in the long run. By restructuring the corporate and banking sectors, the reforms helped restore confidence in the economy, leading to increased investment and consumption. The labor market reforms, which increased flexibility, can also be viewed through a Keynesian lens as measures that helped adjust to the economic shock by allowing the labor market to absorb the impact more effectively.

Many developing countries still face economic stagnation and enormous development problems. These countries can learn valuable lessons from South Korea’s rapid economic transformation. Key takeaways include the importance of strategic government intervention in guiding industrial policy, the need for strong institutions and regulatory frameworks, and the benefits of investing in education and human capital. South Korea’s focus on export-led growth and innovation-driven policies also highlights the significance of integrating into global markets and continuously upgrading technological capabilities. Additionally, the country's response to the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis underscores the importance of financial stability and the ability to implement effective structural reforms during economic downturns [12].

6.Conclusion

South Korea’s transformation from a developing nation to a developed economy is a testament to the effectiveness of strategic planning, government intervention, and adaptability in overcoming economic challenges. This paper examines how South Korea’s Five-Year Plans laid the foundation for rapid industrialization and economic growth by focusing on infrastructure development, export-led growth, and the diversification into heavy industries. These plans not only facilitated the country's transition from an agrarian economy to an industrial powerhouse but also set the stage for the financial stability that would become crucial during the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. The crisis itself, though devastating, became a turning point for South Korea, prompting essential structural reforms in the corporate, banking, and labor sectors. These reforms, backed by the $58 billion IMF bailout, stabilized the economy, restored investor confidence, and paved the way for South Korea’s continued growth and resilience. The analysis underscores the importance of strong institutions, financial discipline, and proactive policy measures in achieving sustained economic development. South Korea’s experience offers valuable lessons for other developing countries on the critical role of strategic intervention and structural reforms in fostering long-term economic stability and growth.

Despite these insights, the analysis is not without limitations. The primary focus on qualitative analysis may not fully capture the complex economic dynamics at play, and the historical emphasis may overlook more recent developments that continue to shape South Korea’s economy. Moreover, while South Korea’s experience provides a robust framework for understanding economic development, the unique cultural, political, and historical contexts of other developing countries may limit the direct applicability of these strategies. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating quantitative analysis to provide a more comprehensive understanding of South Korea’s economic evolution. Additionally, examining the impact of contemporary global economic trends, technological advancements, and regional geopolitical shifts could offer a more nuanced perspective on South Korea’s ongoing economic journey. Further studies could also explore how other countries can adapt South Korea’s strategies to their specific contexts, contributing to a broader understanding of development economics in an increasingly interconnected world.

References

[1]. Bunge, F. M. (1982) South Korea, a country study. Headquarters, Department of the Army, DA Pam 550-41.

[2]. World Bank. (2022) GDP (current US$) - Korea, Rep. World Bank Database. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=KR

[3]. Korea Development Institute. (2017) Korea Development Institute: Promoting growth, sharing prosperity. Retrieved from https://www.kdi.re.kr/res/img/brochure/KDI_brochure_eng_2017.pdf

[4]. Chung, K. H. (1974) Industrial Progress in South Korea. Asian Survey, 14(5), 439-455.

[5]. King, M. R. (2001) Who triggered the Asian financial crisis? Review of International Political Economy, 8(3), 438-466.

[6]. Lee, J. W. (2000) The aftermath of the Asian financial crisis for South Korea. The Journal of the Korean Economy, 1(1), 1-21.

[7]. Crotty, J. and Lee, K.-K. (2004) Was the IMF's imposition of economic regime change in Korea justified? A critique of the IMF's economic and political role before and after the crisis. PERI Working Papers, 77.

[8]. Haggard, S., Lim, W. and Kim, E. (2003) Economic crisis and corporate restructuring in Korea: Reforming the Chaebol. Cambridge University Press.

[9]. Banker, R. D., Chang, H. and Lee, S. Y. (2010) Differential impact of Korean banking system reforms on bank productivity. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(7), 1450-1460.

[10]. Fleckenstein, T. and Lee, S. C. (2017) The politics of labor market reform in coordinated welfare capitalism: Comparing Sweden, Germany, and South Korea. World Politics, 69(1), 144-183.

[11]. Palley, T. I. (2013) Keynesian, classical and new Keynesian approaches to fiscal policy: Comparison and critique. Review of Political Economy, 25(2), 179-204.

[12]. Domjahn, T. M. (2013) What (if anything) can developing countries learn from South Korea?. Asian Culture and History, 5(2), 16-24.

Cite this article

Huang,J. (2024). South Korea: Becoming a Developed Nation Through Reforms and Macroeconomic Policies. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,141,37-43.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICFTBA 2024 Workshop: Finance's Role in the Just Transition

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Bunge, F. M. (1982) South Korea, a country study. Headquarters, Department of the Army, DA Pam 550-41.

[2]. World Bank. (2022) GDP (current US$) - Korea, Rep. World Bank Database. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=KR

[3]. Korea Development Institute. (2017) Korea Development Institute: Promoting growth, sharing prosperity. Retrieved from https://www.kdi.re.kr/res/img/brochure/KDI_brochure_eng_2017.pdf

[4]. Chung, K. H. (1974) Industrial Progress in South Korea. Asian Survey, 14(5), 439-455.

[5]. King, M. R. (2001) Who triggered the Asian financial crisis? Review of International Political Economy, 8(3), 438-466.

[6]. Lee, J. W. (2000) The aftermath of the Asian financial crisis for South Korea. The Journal of the Korean Economy, 1(1), 1-21.

[7]. Crotty, J. and Lee, K.-K. (2004) Was the IMF's imposition of economic regime change in Korea justified? A critique of the IMF's economic and political role before and after the crisis. PERI Working Papers, 77.

[8]. Haggard, S., Lim, W. and Kim, E. (2003) Economic crisis and corporate restructuring in Korea: Reforming the Chaebol. Cambridge University Press.

[9]. Banker, R. D., Chang, H. and Lee, S. Y. (2010) Differential impact of Korean banking system reforms on bank productivity. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(7), 1450-1460.

[10]. Fleckenstein, T. and Lee, S. C. (2017) The politics of labor market reform in coordinated welfare capitalism: Comparing Sweden, Germany, and South Korea. World Politics, 69(1), 144-183.

[11]. Palley, T. I. (2013) Keynesian, classical and new Keynesian approaches to fiscal policy: Comparison and critique. Review of Political Economy, 25(2), 179-204.

[12]. Domjahn, T. M. (2013) What (if anything) can developing countries learn from South Korea?. Asian Culture and History, 5(2), 16-24.