1. Introduction

With the revolution and rapid changes in technology, young leadership has emerged as a dominant force within contemporary companies. For instance, the average age of leaders at Google is 28, and the company asserts that young leaders excel in encouraging employees to voice their opinions, aligning with their slogan: “when employees speak up, the company wins.” Consequently, young leaders have become a focal point of interest, and research on leader age has expanded, particularly concerning antecedents, moderators, and outcomes, with a specific emphasis on employee voice behavior.

Albert Hirschman [1] was among the first to highlight the significance of employee voice behavior, wherein employees speak up to instigate change rather than accept an ineffective or inefficient status quo. He termed this behavior "employee voice" and argued that it plays a crucial role in helping organizations adapt to an ever-evolving business landscape. Management literature consistently underscores the importance of employee voice and the necessity of effective communication within organizations [2] [3]. Recognizing the critical role of voice behavior in achieving organizational success and averting potential crises, researchers have sought to identify the contextual and motivational factors that promote subordinates' voice behaviors. They have found that various leadership behaviors, including leadership style, class, and employee age, impact voice behavior. Among these factors, leader age has been identified as a key element, yet its specific influence remains underexplored.

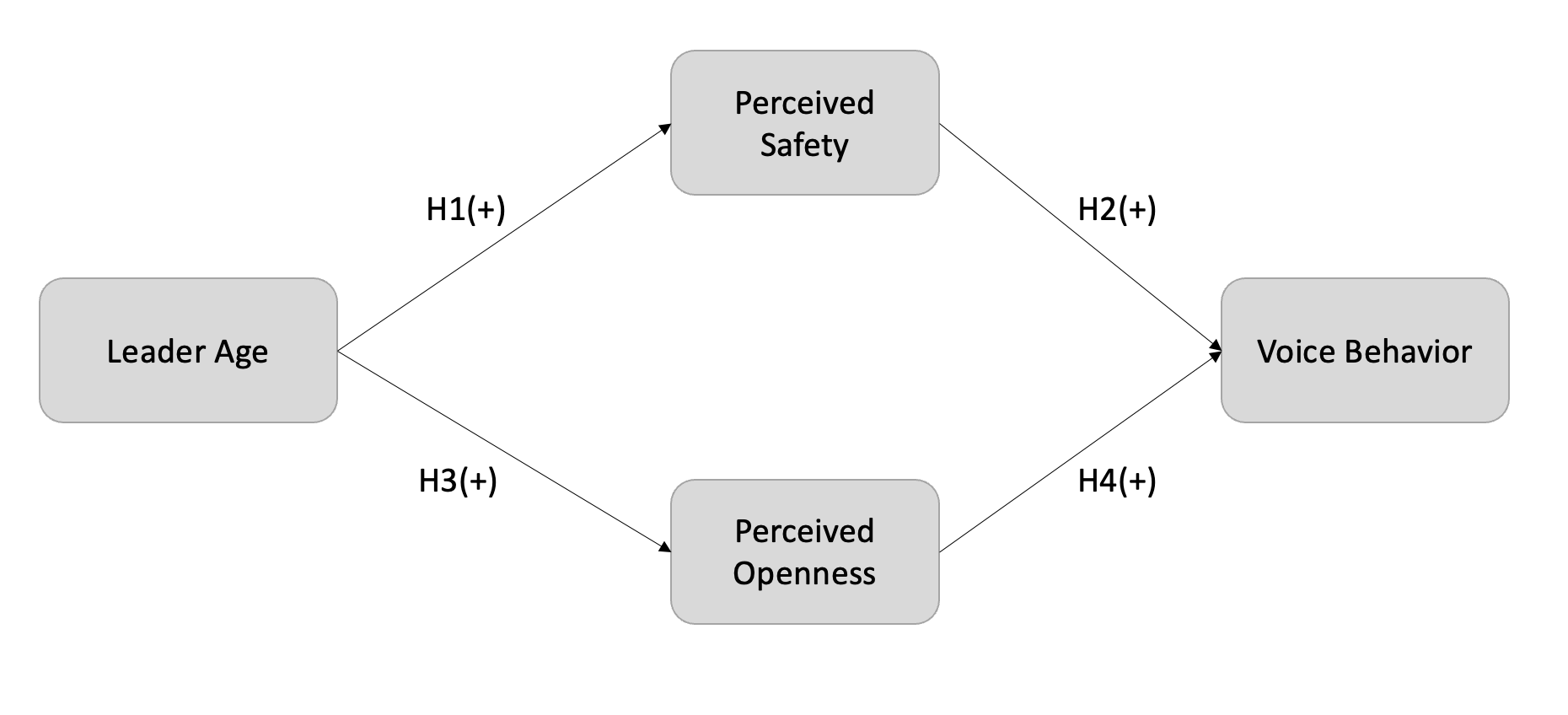

This study aims to address two primary questions: (1) How do young leaders affect employee voice behavior within groups? and (2) What role do perceived safety and openness play in this relationship? The objective is to fill the gap in existing research by examining the influence of young leaders on promoting subordinates' voice behaviors through these mediators.

Firstly, the study posits that young leaders can enhance voice behaviors through two mediators: perceived openness and perceived safety. Previous research has established a positive relationship between openness and subordinates' voice behaviors [4]. Additionally, perceived safety has been shown to be positively related to subordinates' voice behavior [5]. From a leadership perspective, young leaders are often seen as innovative and open to new ideas [6]. From the subordinates' perspective, they may feel more comfortable and trusting when presenting bold suggestions to young leaders, who are perceived as more receptive and supportive.

Secondly, this study investigates whether leader age can serve as an antecedent influencing employee voice behavior. Researchers have highlighted the growing importance of demographics within organizations, surpassing concerns related to technology or financial incentives [7].

Drawing on Resource-Based Theory, which suggests that resources are valuable and irreplaceable in entrepreneurship, this study identifies perceived safety and openness as two critical resources that can positively correlate with employees' voice behavior. To explore this, the study designed a field survey to investigate how does leadership age influences employee’s voice behavior through these two pipelines.

The findings from the study reveal that leader age is negatively correlated with perceived safety and openness. Specifically, young leaders are more likely to foster an environment where subordinates feel psychologically safe and open to expressing their ideas. This, in turn, enhances subordinates' voice behavior, with the effect being particularly pronounced among younger subordinates.

In conclusion, this study makes significant contributions to the literature on employee voice behavior. Firstly, it empirically and theoretically establishes leader age as a critical antecedent influencing subordinates' voice behavior. Secondly, it offers practical insights for organizations seeking to enhance employee voice behavior by highlighting the importance of fostering psychological safety and openness through young leadership. By addressing these factors, organizations can create a more dynamic and responsive work environment, ultimately driving success and innovation.

The article is structured as follows: the chapter 2 reviews previous studies and finds out research gaps. The chapter 3 of this article proposes hypotheses, and deeply discusses the role of psychological safety and openness. The chapter 4 describes the study process including how do we design the survey, distribute and collect data and illustrates the analysis process. The chapter 5 proposes contributions and limitations of the research, which enable a better understanding of how young leaders promote subordinates’ voice behavior.

2. Literature Review

In this section, I am going to review previous studies on voice behavior, perceived openness, perceived safety and leadership.

2.1. Voice Behavior

Extensive research has been conducted on voice behavior, yielding significant insights into its various dimensions and implications. Van Dyne et al. [8] defines voice behavior as the act of speaking up with suggestions and concerns. This definition has been expanded by other scholars who view voice behavior as actions that proactively challenge the status quo and advocate for constructive changes within an organization.

Voice behavior can be categorized into two primary types: promotive and prohibitive voice behavior [9]. Promotive voice behavior involves employees speaking up about their innovations, new ideas, and suggestions aimed at fostering an ideal future state. This type of voice behavior is forward-looking and seeks to enhance organizational processes and outcomes. In contrast, prohibitive voice behavior entails the expression of concerns or identification of undesirable situations within the working environment. This may include reporting incidents or pointing out colleagues' behaviors that could negatively impact the group.

The significance of voice behavior in organizational settings cannot be overstated. Whether promotive or prohibitive, voice behavior serves as a critical mechanism for improving the work environment. Several studies have underscored the importance of voice behavior in work groups, highlighting its role as a pivotal factor for organizational sustainability [10]. Voice behavior is often viewed as behavior that extends beyond normal role expectations or job requirements, ultimately benefiting the organization [11] [12] [13].

Over the decades, scholars have devoted considerable effort to understanding the repercussions of voice behavior failure within groups. For instance, Janis [14] and Kelman & Hamilton [15] have documented the detrimental effects that can arise when employees do not feel empowered to speak up. These failures can lead to missed opportunities for improvement, perpetuation of inefficiencies, and even catastrophic organizational outcomes. The literature on voice behavior has also explored the conditions under which employees are more likely to engage in voice behavior. Factors such as leadership style, organizational culture, and individual psychological safety have been identified as significant determinants. For example, leaders who foster an open and inclusive environment are more likely to encourage voice behavior among their subordinates. Similarly, organizations that prioritize psychological safety create a climate where employees feel secure in expressing their ideas and concerns without fear of retribution.

In conclusion, voice behavior is a multifaceted construct that plays a vital role in organizational dynamics. Its classification into promotive and prohibitive types provides a nuanced understanding of how employees can contribute to organizational improvement. The extensive body of research highlights the importance of fostering an environment that encourages voice behavior, thereby enhancing organizational sustainability and effectiveness. Future research should continue to explore the antecedents and outcomes of voice behavior, as well as the mechanisms through which it can be effectively promoted within organizations.

2.2. Psychological safety

Perceived safety, as defined by Ayim and Salminen [16], refers to the perception of the consequences of interpersonal risks within the working environment. It embodies the belief that engaging in behaviors perceived as risky, such as voicing ideas or concerns, will not result in personal harm [4]. From an individual perspective, perceived safety is the conviction that one will not face punishment or humiliation for expressing ideas, asking questions, voicing concerns, or admitting mistakes. From a team perspective, it is the collective belief among team members that they can speak up without fear of embarrassment, rejection, or retribution from their peers.

Extensive research has highlighted the pivotal role of psychological safety in various organizational outcomes. For instance, Mao and Tian [17] suggests that perceived psychological safety significantly influences work engagement, thereby enhancing employees' commitment and involvement in their tasks. Similarly, Higgins et al. [18] has demonstrated that psychological safety positively impacts organizational performance by fostering an environment conducive to innovation and productivity. Additionally, psychological safety acts as a boundary condition for self-leadership, as noted by Kirsi et al. [19], indicating that individuals are more likely to exhibit self-leadership behaviors in psychologically safe environments.

Moreover, psychological safety has been identified as a crucial factor influencing voice behavior. Ashford et al. [20] and Edmondson [21] have extensively documented the relationship between psychological safety and employees' willingness to speak up. When employees perceive their environment as psychologically safe, they are more inclined to share their ideas, concerns, and feedback, thereby contributing to organizational learning and improvement.

In conclusion, perceived safety is a multifaceted construct that plays a critical role in shaping various organizational behaviors and outcomes. From enhancing work engagement and organizational performance to facilitating voice behavior, psychological safety serves as a foundational element in creating a supportive and innovative work environment. Future research should continue to investigate the mechanisms through which psychological safety can be fostered and its broader implications for organizational success.

2.3. Perceived Openness

Perceived openness is a multifaceted construct encompassing imagination, creativity, intellectual curiosity, and an appreciation for aesthetic experiences. It broadly pertains to an individual's capacity and inclination to engage with and process complex stimuli [22]. This trait reflects a person's willingness to embrace new ideas, experiences, and perspectives, characterized by an open-minded approach and a natural curiosity about the world.

Individuals who exhibit high levels of openness are more likely to seek out novel experiences and engage in creative endeavors. They demonstrate a propensity for thinking innovatively and making connections between disparate concepts and ideas. This cognitive flexibility allows them to approach problems and opportunities with a fresh perspective, often leading to innovative solutions and creative outputs.

In organizational settings, perceived openness is a critical attribute for leaders. When leaders exhibit openness, they create an environment where subordinates feel encouraged to share their ideas and suggestions. According to Yue [23], subordinates perceive their leaders as open when they are receptive to input and incorporate these contributions into decision-making processes. This perceived openness fosters a culture of upward communication, where employees feel valued and heard.

Research has shown that managerial openness can significantly influence various organizational dynamics. For instance, Xu et al. [24] found that managerial openness moderates the relationship between issue importance and public voice tactics, suggesting that open leaders are more likely to consider and act upon critical issues raised by employees. Additionally, Ashford et al. [20] demonstrated that openness is positively correlated with employees' motivation to speak up, indicating that when leaders are perceived as open, employees are more likely to engage in voice behavior.

In conclusion, perceived openness is a vital trait that enhances both individual and organizational outcomes. Leaders who exhibit openness not only foster a culture of innovation and creativity but also encourage upward communication and employee engagement. This trait is instrumental in creating a dynamic and responsive organizational environment, where new ideas and perspectives are valued and leveraged for continuous improvement. Future research should continue to explore the mechanisms through which perceived openness can be cultivated and its broader implications for organizational success.

2.4. Leadership

Leadership has long been a popular topic of research, with numerous studies exploring its definition, classification, and effects from various perspectives. Leadership is often demonstrated through different forms of formal and informal interactions and exchanges between individuals [25]. From a process-oriented perspective, Yukl [26] defines leadership as the ability to exert significant influence on subordinates, motivating them to achieve specific objectives while maintaining group cohesion. Leadership is seen as a positive yet persuasive process that inspires followers and directs their efforts toward achieving individual, team, and organizational goals [27]. In addition, Glisson [28] highlights that leadership has the power to create an enthusiastic and optimistic organizational environment, emphasizing that this power stems from leaders’ ability to influence followers’ attitudes and perspectives. Therefore, leadership can be described as an undeniable force that shapes the behaviors and performance of colleagues and employees.

Leader age refers to the chronological age of individuals in leadership roles, which often serves as a proxy for life experience, maturity, and generational perspectives [29]. It is an essential demographic variable that can influence leadership style, decision-making processes, and interpersonal dynamics within organizations. Leader age affects not only how leaders perceive their roles but also how they are perceived by their subordinates. Research highlights significant variations in leadership styles across different age groups. Younger leaders are often associated with transformational and participative leadership styles, characterized by openness to innovation, risk-taking, and inclusivity. In contrast, older leaders may lean toward transactional or directive leadership styles, focusing on stability, structure, and efficiency [30]. These differences in leadership approaches can have downstream effects on organizational culture and employee behavior.

The age of a leader can impact various organizational outcomes, including employee performance, innovation, and team dynamics. Studies suggest that younger leaders may foster a more dynamic and adaptable work environment, whereas older leaders often emphasize long-term goals and organizational resilience [31]. However, excessive reliance on either younger or older leaders can lead to challenges, such as a lack of experience in the former or reduced adaptability in the latter [32]. In addition, leader age influences how subordinates perceive and respond to leadership. Younger leaders may face challenges in establishing credibility and authority, particularly in traditional or hierarchical organizations. Conversely, older leaders are often perceived as more credible and experienced but may encounter resistance in rapidly changing industries where adaptability is key.

3. Research Framework

3.1. Leader Age and Psychological Safety

Psychological safety is a crucial aspect of workplace dynamics, particularly as it pertains to how subordinates perceive the value of their proposed ideas within a group. When employees feel that they can contribute ideas without the fear of negative consequences, they are less concerned about making mistakes and more likely to engage actively in work-related discussions [33]. This environment fosters a culture where employees are not overly cautious and can focus on innovation and improvement without the threat of personal loss. Conversely, if employees feel threatened by their superiors and anticipate significant personal repercussions for suggesting ideas, they are more inclined to remain silent [8]. Both promotive and prohibitive voice behaviors—which include raising concerns, offering criticisms, and proposing improvements—require a supportive environment. The openness and inclusiveness of a leader play a critical role in determining whether employees feel safe to express their opinions.

Research indicates that older leaders, compared to their younger counterparts, are generally perceived as easier to get along with and more approachable [6]. Thus, employees are more likely to communicate with older leaders with relax. In addition, studies suggest that subordinates view older leaders as being more likely to resolve conflicts and reduce tensions in the workplace. For example, older leaders have been found to be significantly more effective in mitigating militarized disputes compared to younger leaders. With strong belief in older leaders, employees are more willing to express their opinions and concerns because they don’t worry about the consequences. Furthermore, older leaders are often seen as having more experience, wisdom, and a greater capacity for empathy, which can contribute to a more supportive and safer psychological environment for their subordinates. This increased sense of safety can encourage more open communication, greater collaboration, and a higher likelihood of subordinates voicing their opinions and concerns. Therefore, we predict:

Hypothesis 1: Leader age is positively correlated with perceived psychological safety of subordinates.

3.2. Perceived Safety and Voice Behavior

Previous research indicates that employees’ attitudinal evaluations of specific behaviors are significantly shaped by their perceptions of the outcomes, whether positive or negative. This notion is particularly pertinent in the context of organizational behavior, especially when considering the concept of psychological safety. Psychological safety is defined as an individual’s belief that they can express ideas, raise questions, voice concerns, or admit mistakes without fearing retaliation or adverse consequences to their professional standing or career. It serves as a critical component in fostering a workplace environment where employees feel acknowledged and respected, which subsequently influences their likelihood to engage in voice behavior.

Voice behavior, characterized as the proactive communication of suggestions, concerns, or feedback intended to enhance organizational effectiveness, is deeply impacted by psychological safety. When employees perceive the workplace as a space where they can share their thoughts without the risk of negative repercussions, their propensity to exhibit voice behavior increases. This behavior benefits organizations by facilitating innovation, optimizing processes, and enabling early detection of potential issues. Research by Van Dyne et al. [8] confirms the mediating role of psychological safety in the relationship between superior-subordinate interactions and voice behavior. Their findings emphasize that leaders who cultivate psychological safety create an environment where employees feel more comfortable voicing their opinions and recommendations, highlighting the critical role of leadership in shaping organizational communication climates. Additionally, Liang et al. [5] demonstrate that psychological safety not only encourages voice behavior but also plays a pivotal role in mitigating employee silence. Their study reveals that employees who feel psychologically safe are more likely to engage in promotive voice behaviors, such as offering constructive ideas and suggestions for improvement, and are less likely to withhold concerns or criticisms. This dual effect of fostering open communication while reducing fear of speaking up is essential for sustaining a dynamic and adaptive organizational culture.

In conclusion, the literature on the psychological antecedents of voice behavior underscores the central role of psychological safety. As a fundamental element, psychological safety enables employees to actively contribute to organizational dialogue, thereby driving innovation and continuous improvement. Based on these insights, this study posits:

Hypothesis 2: Perceived safety perceived by subordinates is positively correlated with their voice behaviors.

3.3. Leader Age and Perceived Openness

Voice behavior refers to the proactive action employees take to address workplace issues and challenges by communicating their suggestions, concerns, or ideas. This behavior plays a critical role in organizational problem-solving and innovation. When leaders exhibit positive signals, such as openness and appreciation for subordinates’ input, employees are generally more inclined to speak up. Such leadership behaviors are instrumental in fostering employees’ initial motivation to express their thoughts and engage in voice behavior. The perceived receptiveness of leaders is essential in creating a psychologically safe environment where employees feel valued and empowered to contribute to workplace improvements.

Theoretically, traits have been conceptualized as “intra-individually consistent and inter-individually distinct propensities to behave in some identifiable way”. This definition highlights that personality traits are stable characteristics within an individual while remaining unique across individuals. These traits can influence behaviors in organizational settings, including voice behavior. Leaders’ traits, particularly those associated with openness, play a significant role in shaping subordinates’ perceptions and behaviors. From a resource-based perspective, resources can be categorized into buyable and non-buyable assets. Leaders’ personality traits, particularly those that align with non-buyable resources, are invaluable as they cannot be replicated or purchased. Aged leaders are often endowed with traits that subordinates perceive as non-buyable resources, such as wisdom, tolerance, and openness. Openness, one of the Big Five personality dimensions, is a critical trait in fostering voice behavior. Subordinates often perceive openness as a signal that leaders are inclusive, tolerant, and open-minded. This perception is amplified in aged leaders, whose age itself may serve as a strong signal of these qualities. According to Sebba et al. [6], subordinates are more likely to interpret an older leader’s openness as an indication of their willingness to listen to diverse perspectives and value different opinions. The perception of openness is significant because it aligns with the psychological needs of subordinates to feel respected and supported when expressing their ideas. Furthermore, openness as a personality trait functions as a resource in the workplace, enhancing subordinates’ willingness to engage in voice behavior. When leaders demonstrate openness, subordinates are more likely to interpret this as an invitation to participate in organizational discourse. This perception reduces the psychological barriers often associated with speaking up, such as fear of rejection or criticism. As a result, subordinates are more inclined to share their insights, which can lead to organizational benefits such as innovation, improved processes, and better decision-making.

From a broader perspective, the resource-based view positions leaders’ traits, particularly those associated with openness, as essential organizational assets. Aged leaders, by virtue of their perceived experience and wisdom, are uniquely positioned to leverage this trait to foster an environment where subordinates feel empowered to voice their concerns and ideas. Their perceived inclusiveness and tolerance can significantly contribute to creating a collaborative and dynamic workplace culture.

In conclusion, voice behavior is a critical organizational process influenced by subordinates’ perceptions of their leaders’ traits. Leaders who exhibit openness, particularly aged leaders, send strong signals of inclusivity and tolerance, encouraging subordinates to speak up. This alignment of leadership traits with subordinates’ psychological needs underscores the importance of fostering an environment where voice behavior is not only accepted but actively encouraged, contributing to organizational growth and success. Therefore, we predict:

Hypothesis 3: Leader age is positively related to perceive openness.

3.4. Voice Behavior and Perceived Openness

Perceived openness is a critical factor in various organizational contexts, significantly influencing decision-making processes and shaping the dynamics between leaders and subordinates. Open communication between supervisors and subordinates fosters higher levels of job satisfaction among employees compared to when such relationships are perceived as “closed” [34]. The perception of openness originates from leaders and is characterized by a two-way interaction that resonates between leaders and their subordinates.

When leaders exhibit reluctance to accept input or feedback from their subordinates, employees are less likely to challenge their authority or express their opinions. Hornstein [35] highlights that many employees lack the confidence to voice concerns or ideas when their managers display an unwillingness to engage in open dialogue. This reluctance on the part of managers not only diminishes the level of openness within the organization but also undermines the trust and psychological safety necessary for constructive communication. Conversely, when managers demonstrate personal interest in their subordinates, actively listen to their concerns, and take tangible actions in response, they convey a sense of psychological safety. This behavior reduces the perceived risks associated with honest communication, encouraging employees to share their thoughts and suggestions [4]. In such an environment, employees are more inclined to engage in voice behavior, as they feel their input is valued and will be acted upon.

Thus, the degree of perceived openness within an organization, largely influenced by the attitudes and actions of leaders, plays a pivotal role in fostering an environment conducive to voice behavior. Leaders who prioritize active listening, responsiveness, and genuine interest in their subordinates’ perspectives create a culture of openness that enhances employee engagement and drives organizational growth. Therefore, we suggest:

Hypothesis 4: Perceived openness has a positive effect on voice behavior.

Figure 1: Research Framework and Hypotheses

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

This study employs a quantitative research design using a survey method to investigate the relationship between leader age and voice behavior. A survey approach was chosen for its efficiency in collecting data from a large sample and its ability to capture individual perceptions and attitudes. We selected the educational institute as the research context for several key reasons. First, the phenomenon could minimize potential confounding factors that could influence our findings. For example, in a social media company, variables such as performance pressure or salary could drive subordinates to voice their opinions regardless of the leader’s age, making it difficult to test our hypotheses accurately. Second, the chosen institute has a total of over 2,000 employees, providing a sufficient sample size for robust data analysis. Third, and importantly, the daily interactions between leaders and subordinates in this real-world setting allow for meaningful evaluations of perceived leader openness, psychological safety, and subordinates’ voice behavior, facilitating the empirical testing of our hypotheses.

4.2. Research Procedure

All surveys were administered in English and hosted on www.credamo.com, a reliable data collection platform frequently utilized in prior academic studies. The surveys were distributed to participants via WeChat, a widely used Chinese social media and communication application, ensuring convenient access for respondents. The data collection process was conducted over the course of several weeks. A total of 161 subordinates completed the survey. The questionnaire collected demographic information, including age, gender, etc., and participants were also asked to provide details about their leaders, such as their age, and to evaluate their leaders on scales measuring perceived openness and psychological safety. Additionally, the survey assessed how frequently the subordinates were likely to offer suggestions or feedback to their leaders, reflecting their voice behavior.

To facilitate data integration and ensure accurate matching between responses from leaders and subordinates, all participants were required to provide the last four digits of their phone numbers as identifiers. Similarly, they were asked to input the last four digits of their leader’s or subordinate’s phone number. This process streamlined the subsequent classification and merging of data from paired respondents, ensuring a seamless and efficient analysis.

4.3. Measures

Perceived Openness. Perceived openness was measured with 5 items (1) Do you agree that you can easily reach the leader of the company and get a response when you need it? (1= “Strongly disagree” to 5= “Strongly agree”). (2) Do you agree that you come up with new ideas, you are supported and valued in the organization? (1= “Strongly disagree” to 5= “Strongly agree”). (3) Do you agree that the organization should be transparent in its decision-making process and inform employees in a timely manner? (1= “Strongly disagree” to 5= “Strongly agree”). (4) Do you agree that there is an atmosphere of mutual trust within your organization that allows employees to share their true thoughts and feelings? (5) Do you agree that when a problem arises within the organization, management will invite relevant employees to participant in the discussion and resolution of the problem?

Perceived Safety. Perceived safety is measured with 6 items from prior research: (1) Do you agree that you feel safe in your workplace and are not under threat of any physical or psychological harm? (1= “Strongly disagree” to 5= “Strongly agree”). (2) Do you agree that you are free to express your opinions and ideas in a team without fear of ridicule or criticism? (1= “Strongly disagree” to 5= “Strongly agree”). (3) Do you agree that when you disagree or criticize, you fear negative repercussions or retaliation? (1= “Strongly disagree” to 5= “Strongly agree”). (4) Do you agree that in a high-pressure situation, you still feel that the organization is able to provide you with a safe and supportive environment? (1= “Strongly disagree” to 5= “Strongly agree”). (5) When conflicts or disputes arise, do you agree that the organization will handle them fairly and that the interests and opinions of all parties will be treated equally? (1= “Strongly disagree” to 5= “Strongly agree”). (6) Do you agree that you will be able to develop your career in the organization with a safe and supportive environment? (1= “Strongly disagree” to 5= “Strongly agree”).

Voice Behavior. We adapted straightforward item to measure voice behavior from Xia et al. (2016) to fit the company setting.

Control variables. We did not control for between-person level variable such as age, gender educational level, organizational tenure, and position in one’s organization because they were inherently controlled in this model; results were robust when we did control for them.

4.4. Analysis

According to literature, linear regression is used to demonstrate the hypotheses which is shown as follows:

Y = aX + b +e

Specifically, four research models are adopted in the study due to four distinct hypotheses.

Perceived Safety = a1*Leader Age + b1 +e

Where a1 represents the slope of the model (a), b1 means intercept of the model (a) and e is the residuals.

Voice Behavior = a2*Perceived Safety+ b2 +e

Where a2 represents the slope of the model (b), b2 means intercept of the model (b) and e is the residuals.

Perceived Openness = a3*Leader Age + b3 +e

Where a3 represents the slope of the model (c), b3 means intercept of the model (c) and e is the residuals.

Voice Behavior = a4*Perceived Openness + b4 +e

Where a4 represents the slope of the model (d), b4 means intercept of the model (d) and e is the residuals.

4.5. Results

Table 1: Empirical Results of Hypotheses

Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

Perceived Safety | 0.865*** | |||

Perceived Openness | 0.902*** | |||

Voice Behavior | 0.815*** | 0.761*** | ||

R2 | 0.796 | 0.705 | 0.781 | 0.674 |

The chart above presents the results of the analysis. In Model 1, the coefficient (b) is 0.865, which is greater than 0, and the p-value is 0.02, less than 0.1, indicating support for Hypothesis 1. In Model 2, the coefficient (b) is 0.815, greater than 0, with a p-value of 0.01, also less than 0.1, providing support for Hypothesis 2. In Model 3, the coefficient (b) is 0.902, greater than 0, and the p-value is 0.015, again below 0.1, suggesting that Hypothesis 3 is supported. Finally, in Model 4, the coefficient (b) is 0.761, greater than 0, and the p-value is 0.01, less than 0.1, which indicates support for Hypothesis 4.

5. Discussion

5.1. Contribution

This study makes significant contributions to the field of organizational behavior by exploring the impact of leader age on voice behavior, with a particular focus on the mediating roles of perceived openness and psychological safety. First, this research extends the literature on leadership and voice behavior by providing empirical evidence of how leader age influences employees’ willingness to speak up in organizational contexts. While prior studies have explored various leadership traits and behaviors, few have specifically examined the role of leader age as a factor shaping voice behavior, thereby filling a gap in the existing research.

The study also contributes to the growing body of knowledge on the importance of perceived openness and psychological safety in fostering voice behavior. The findings reveal that when leaders are perceived as open and inclusive, employees are more likely to engage in voice behavior, suggesting that a leader’s age, as a proxy for experience and perceived openness, plays a crucial role in shaping employees’ willingness to express concerns and ideas. Moreover, the mediation analysis confirms that perceived openness and psychological safety significantly mediate the relationship between leader age and voice behavior, highlighting the importance of creating an environment where employees feel safe to speak up without fear of negative repercussions.

Additionally, the use of survey data in a real-world organizational context strengthens the external validity of the study. By examining these dynamics in a practical setting, this research provides actionable insights for organizations aiming to improve employee engagement, communication, and innovation. Leaders, especially older ones, can use the findings to foster a more open and psychologically safe environment, thereby promoting voice behavior that leads to improved organizational outcomes.

5.2. Limitation

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the data collected was based on self-reported surveys, which may introduce biases such as social desirability bias or common method variance. Participants may have overestimated their perceived openness or safety within the organization, leading to potential inaccuracies in the data. Future studies could incorporate objective measures or multiple sources of data to validate these findings.

Second, the study’s cross-sectional design limits the ability to infer causality. While the results suggest a positive relationship between leader age, perceived openness, and voice behavior, the direction of causality cannot be conclusively established. Longitudinal studies that track changes over time would provide more robust insights into the causal mechanisms behind these relationships.

Third, the sample size and demographic homogeneity may limit the generalizability of the findings. The study was conducted within a single organization, which may not reflect the experiences of employees in different industries or organizational contexts. Future research could expand the sample to include a broader range of organizations to assess the external validity of the results.

Lastly, while the study focuses on leader age, other factors such as leadership style, organizational culture, or employee personality traits may also influence voice behavior. Further research could explore these additional variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that shape voice behavior in organizations.

6. Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into the impact of leader age on voice behavior within organizations, with a particular emphasis on the mediating roles of perceived openness and psychological safety. By examining how these factors interact, the study contributes to the understanding of the conditions under which employees are most likely to engage in voice behavior—an essential aspect of organizational communication, innovation, and improvement.

The findings reveal that leader age plays a significant role in shaping employees’ willingness to speak up. Older leaders, who are often perceived as more experienced and open-minded, create an environment where subordinates feel psychologically safe to share their ideas and concerns. This perception of openness is crucial in fostering a culture of constructive communication and organizational learning. Additionally, the study demonstrates that psychological safety and perceived openness act as mediators in the relationship between leader age and voice behavior, highlighting the importance of leaders’ ability to build an inclusive and supportive work environment.

The practical implications of these findings are far-reaching. Organizations seeking to improve employee engagement and foster innovation should consider the role of leadership characteristics—particularly leader age—in encouraging voice behavior. Leaders, especially those with greater experience, should be aware of the power they hold in shaping an organizational climate that promotes open communication. By actively demonstrating openness, listening to feedback, and addressing employee concerns, leaders can cultivate a work environment that empowers employees to contribute their ideas and suggestions.

While this study contributes to the understanding of the dynamics between leader age, perceived openness, and voice behavior, it also opens avenues for future research. Exploring additional factors such as leadership style, organizational context, and employee characteristics can provide further insights into the complex nature of voice behavior and the conditions that enhance it. Ultimately, fostering a culture of openness and psychological safety is crucial for organizations aiming to stay competitive and innovative in today’s rapidly changing work environment.

References

[1]. Hirschman, A. O. (1987). Exit and voice. The New Palgrave: A dictionary of economics, 1.

[2]. Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25, 706–725.

[3]. Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2008). Employee silence on critical work issues: The cross level effects of procedural justice climate. Personnel Psychology, 61, 37–68.

[4]. Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. 2007. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the. door really open? Academy of Management Journal.

[5]. Liang, J., Farh, C. I., & Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management journal, 55(1), 71-92.

[6]. Sebba, J., Hunt, F., Farlie, J., Flowers, S., Mulmi, R., & Drew, N. (2009). Youth-led innovation: Enhancing the skills and capacity of the next generation of innovators. NESTA.

[7]. Drucker, P. F. (1996). Your leadership is unique. Leadership, 17(4), 54.

[8]. Dyne, L. V., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of management studies, 40(6), 1359-1392.

[9]. Jian Liang, Crystal I. C. Farh.,& Jing-Lin Farh, 2012. A two-wave examination on: Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice. Academy of Management Journal.

[10]. Li, Y., Zhang, L., & Yan, X. (2022). How does strategic human resource management impact on employee voice behavior and innovation behavior with mediating effect of psychological mechanism. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 920774.

[11]. Groyecka-Bernard, A., Pisanski, K., Frąckowiak, T., Kobylarek, A., Kupczyk, P., Oleszkiewicz, A., ... & Sorokowski, P. (2022). Do voice-based judgments of socially relevant speaker traits differ across speech types?. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 65(10), 3674-3694.

[12]. George, J. M., & Brief, A. P. (1992). Feeling good-doing good: A conceptual analysis of the mood at work-organizational spontaneity relationship. Psychological bulletin, 112(2), 310.

[13]. Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). Organizations and the system concept. Classics of organization theory, 80(480), 27.

[14]. Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink: A psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and fiascoes.

[15]. Kelman, H. C., & Hamilton, V. L. (1989). Crimes of obedience: Toward a social psychology of authority and responsibility. Yale University Press.

[16]. Ayim Gyekye, S., & Salminen, S. (2007). Workplace safety perceptions and perceived organizational support: do supportive perceptions influence safety perceptions?. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 13(2), 189-200.

[17]. Mao, J., & Tian, K. (2022). Psychological safety mediates the relationship between leader–member exchange and employees' work engagement. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 50(3), 31-39.

[18]. Higgins, M. C., Dobrow, S. R., Weiner, J. M., & Liu, H. (2022). When is psychological safety helpful in organizations? A longitudinal study. Academy of Management Discoveries, 8(1), 77-102.

[19]. Sjöblom, K., Juutinen, S., & Mäkikangas, A. (2022). The importance of self-leadership strategies and psychological safety for well-being in the context of enforced remote work. Challenges, 13(1), 14.

[20]. Ashford, S. J., Wellman, N., Sully de Luque, M., De Stobbeleir, K. E., & Wollan, M. (2018). Two roads to effectiveness: CEO feedback seeking, vision articulation, and firm performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(1), 82-95.

[21]. Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav., 1(1), 23-43.

[22]. Tsai, M. H. (2023). Can conflict cultivate collaboration? The positive impact of mild versus intense task conflict via perceived openness rather than emotions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 29(4), 813.

[23]. Yue, D. K. (2024). Impact of Destructive Leadership on Innovative Work Behavior: Exploring the Role of Psychological Safety (Doctoral dissertation).

[24]. Xu, E., Huang, X., Ouyang, K., Liu, W., & Hu, S. (2020). Tactics of speaking up: The roles of issue importance, perceived managerial openness, and managers' positive mood. Human Resource Management, 59(3), 255-269.

[25]. White, L., Currie, G., & Lockett, A. (2016). Pluralized leadership in complex organizations: Exploring the cross network effects between formal and informal leadership relations. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(2), 280-297.

[26]. Portugal, E., & Yukl, G. (1994). Perspectives on environmental leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 5(3-4), 271-276.

[27]. Puni, A., Ofei, S. B., & Okoe, A. (2014). The effect of leadership styles on firm performance in Ghana. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 6(1), 177.

[28]. Glisson, C. (2015). The role of organizational culture and climate in innovation and effectiveness. Human service organizations: management, leadership & governance, 39(4), 245-250.

[29]. Kearney, E. (2008). Age differences between leader and followers as a moderator of the relationship between transformational leadership and team performance. Journal of occupational and Organizational Psychology, 81(4), 803-811.

[30]. McCann, J. T., & Holt, R. A. (2010). Defining sustainable leadership. International Journal of Sustainable Strategic Management, 2(2), 204-210.

[31]. Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2010). The relationships of age with job attitudes: A meta‐analysis. Personnel psychology, 63(3), 677-718.

[32]. Kunze, F., Boehm, S., & Bruch, H. (2013). Organizational performance consequences of age diversity: Inspecting the role of diversity‐friendly HR policies and top managers’ negative age stereotypes. Journal of Management Studies, 50(3), 413-442.

[33]. Gilson, L., Schneider, H., & Orgill, M. (2014). Practice and power: a review and interpretive synthesis focused on the exercise of discretionary power in policy implementation by front-line providers and managers. Health policy and planning, 29(suppl_3), iii51-iii69.

[34]. Jablin, F. M. (1978). Message-response and “openness” in superior-subordinate communication. Annals of the International Communication Association, 2(1), 293-309.

[35]. Hornstein, N. (1986). Situations and Attitudes.

Cite this article

Ding,J. (2025). Speaking or Keeping Silent? Investigating the Impact of Young Leadership on Voice Behavior. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,165,12-24.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Management Research and Economic Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Hirschman, A. O. (1987). Exit and voice. The New Palgrave: A dictionary of economics, 1.

[2]. Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25, 706–725.

[3]. Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2008). Employee silence on critical work issues: The cross level effects of procedural justice climate. Personnel Psychology, 61, 37–68.

[4]. Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. 2007. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the. door really open? Academy of Management Journal.

[5]. Liang, J., Farh, C. I., & Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management journal, 55(1), 71-92.

[6]. Sebba, J., Hunt, F., Farlie, J., Flowers, S., Mulmi, R., & Drew, N. (2009). Youth-led innovation: Enhancing the skills and capacity of the next generation of innovators. NESTA.

[7]. Drucker, P. F. (1996). Your leadership is unique. Leadership, 17(4), 54.

[8]. Dyne, L. V., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of management studies, 40(6), 1359-1392.

[9]. Jian Liang, Crystal I. C. Farh.,& Jing-Lin Farh, 2012. A two-wave examination on: Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice. Academy of Management Journal.

[10]. Li, Y., Zhang, L., & Yan, X. (2022). How does strategic human resource management impact on employee voice behavior and innovation behavior with mediating effect of psychological mechanism. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 920774.

[11]. Groyecka-Bernard, A., Pisanski, K., Frąckowiak, T., Kobylarek, A., Kupczyk, P., Oleszkiewicz, A., ... & Sorokowski, P. (2022). Do voice-based judgments of socially relevant speaker traits differ across speech types?. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 65(10), 3674-3694.

[12]. George, J. M., & Brief, A. P. (1992). Feeling good-doing good: A conceptual analysis of the mood at work-organizational spontaneity relationship. Psychological bulletin, 112(2), 310.

[13]. Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). Organizations and the system concept. Classics of organization theory, 80(480), 27.

[14]. Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink: A psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and fiascoes.

[15]. Kelman, H. C., & Hamilton, V. L. (1989). Crimes of obedience: Toward a social psychology of authority and responsibility. Yale University Press.

[16]. Ayim Gyekye, S., & Salminen, S. (2007). Workplace safety perceptions and perceived organizational support: do supportive perceptions influence safety perceptions?. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 13(2), 189-200.

[17]. Mao, J., & Tian, K. (2022). Psychological safety mediates the relationship between leader–member exchange and employees' work engagement. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 50(3), 31-39.

[18]. Higgins, M. C., Dobrow, S. R., Weiner, J. M., & Liu, H. (2022). When is psychological safety helpful in organizations? A longitudinal study. Academy of Management Discoveries, 8(1), 77-102.

[19]. Sjöblom, K., Juutinen, S., & Mäkikangas, A. (2022). The importance of self-leadership strategies and psychological safety for well-being in the context of enforced remote work. Challenges, 13(1), 14.

[20]. Ashford, S. J., Wellman, N., Sully de Luque, M., De Stobbeleir, K. E., & Wollan, M. (2018). Two roads to effectiveness: CEO feedback seeking, vision articulation, and firm performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(1), 82-95.

[21]. Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav., 1(1), 23-43.

[22]. Tsai, M. H. (2023). Can conflict cultivate collaboration? The positive impact of mild versus intense task conflict via perceived openness rather than emotions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 29(4), 813.

[23]. Yue, D. K. (2024). Impact of Destructive Leadership on Innovative Work Behavior: Exploring the Role of Psychological Safety (Doctoral dissertation).

[24]. Xu, E., Huang, X., Ouyang, K., Liu, W., & Hu, S. (2020). Tactics of speaking up: The roles of issue importance, perceived managerial openness, and managers' positive mood. Human Resource Management, 59(3), 255-269.

[25]. White, L., Currie, G., & Lockett, A. (2016). Pluralized leadership in complex organizations: Exploring the cross network effects between formal and informal leadership relations. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(2), 280-297.

[26]. Portugal, E., & Yukl, G. (1994). Perspectives on environmental leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 5(3-4), 271-276.

[27]. Puni, A., Ofei, S. B., & Okoe, A. (2014). The effect of leadership styles on firm performance in Ghana. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 6(1), 177.

[28]. Glisson, C. (2015). The role of organizational culture and climate in innovation and effectiveness. Human service organizations: management, leadership & governance, 39(4), 245-250.

[29]. Kearney, E. (2008). Age differences between leader and followers as a moderator of the relationship between transformational leadership and team performance. Journal of occupational and Organizational Psychology, 81(4), 803-811.

[30]. McCann, J. T., & Holt, R. A. (2010). Defining sustainable leadership. International Journal of Sustainable Strategic Management, 2(2), 204-210.

[31]. Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2010). The relationships of age with job attitudes: A meta‐analysis. Personnel psychology, 63(3), 677-718.

[32]. Kunze, F., Boehm, S., & Bruch, H. (2013). Organizational performance consequences of age diversity: Inspecting the role of diversity‐friendly HR policies and top managers’ negative age stereotypes. Journal of Management Studies, 50(3), 413-442.

[33]. Gilson, L., Schneider, H., & Orgill, M. (2014). Practice and power: a review and interpretive synthesis focused on the exercise of discretionary power in policy implementation by front-line providers and managers. Health policy and planning, 29(suppl_3), iii51-iii69.

[34]. Jablin, F. M. (1978). Message-response and “openness” in superior-subordinate communication. Annals of the International Communication Association, 2(1), 293-309.

[35]. Hornstein, N. (1986). Situations and Attitudes.