1. Introduction

Despite the regional conflicts and geographical politics, peace and development remain the primary theme of this era [1]. With the irrevocable trend of globalization, international trade has been and will still have been a significant constituent for domestic production. Extensive studies have shown that education imposes a positive influence on exports. Nevertheless, limited studies try to explain through what exact channel does education influence exports. This research focuses on the revelation of the mediation effect of education on exports if there is any.

Export has been an indispensable part in the constitution of an economy, like in one popular method of GDP calculation comprises consumption, investment, government purchases and net exports [2]. And in some Asian countries, for example China, Korea, and Singapore, export has once become one of the most powerful drives for their economies [3]. Export-Led Growth theory has also validated the positive correlation, with the data of 11 countries’, between exports and GDP [4].

This correlation can be roughly quantified. The World Bank Report 2020 mentioned every 1% increase in exports can bring about a 0.7% increase in GDP [5]. This report also declared this interaction is more distinctive in developing countries. Similar finding is also found by IMF. IMF Annual Report 2022 on developing countries over 1970 – 2015, it is declared that an increase of 10% in the proportion of exports to GDP will lead to an average increase from 0.4% to 0.6% in the annual GDP growth rate [6].

Previous research has demonstrated a strong correlation between export intensity and a country's economic development. In other words, it can be highly pragmatic to promote a country's economic development by expanding its export intensity.

When scientists try to study the fundamental drives that influence exports, education is one factor that cannot be overlooked [7]. Multiple theories have proved the impact of education to an economy’s development. New Growth Theory indicates educational accumulation is an endogenous driver of long-term economic growth, and human capital can generate externalities that stimulate growth across the entire economic sector [8]. In Skill-based Trade Theory similar ideas were also mentioned but from more of an export structure perspective. Comparative advantages among countries have been less influenced by resource endowments, but increasingly by human capital and skill composition. Highly skilled labor has become a key factor in shaping the structure of exports, particularly in knowledge-intensive industries [9]. Based on these studies, it is clear that education and exports are closely interlinked.

2. Literature review

As education and exports are both significant to economic development, many scholars have done their research to supplement the theoretical framework. Here are a few classical theories about the internal mechanism among education, exports, and GDP.

2.1. Relation between exports and GDP

Export-Led Growth (ELG) is one unavoidable theory talking about relation between exports and economic growth. The Export-Led Growth (ELG) theory posits that export expansion is a primary driver of economic growth, particularly for developing and emerging economies. Rooted in classical trade theory and gaining prominence in the 1970s and 1980s, ELG suggests that outward-oriented trade policies enhance economic performance by encouraging specialization, achieving economies of scale, and improving resource allocation efficiency [10]. Through export expansion, countries can gain access to larger international markets, attract foreign investment, increase foreign exchange earnings, and stimulate productivity growth.

Hossain formalized this view by demonstrating that the export sector often exhibits higher productivity than the non-export sector and generates positive externalities that spill over into the broader economy [11]. Empirical studies have found significant correlations between export growth and GDP growth in export-oriented countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore [12]. Furthermore, increased export activity can stimulate innovation, improve labor skills, and promote structural transformation in domestic industries.

In this context, the ELG framework provides a useful lens to explore how various factors—such as education and human capital can influence a country's export capacity, and in turn, economic development. It is natural to think developed countries which excel in education and knowledge accumulation will take over the majority of the global exports and dominate the trade. This intuitive concept is proved incorrect by Comparative Advantage Theory.

The theory of comparative advantage, first brought by David Ricardo in 1817, remains one of the foundational concepts in international trade theory. It asserts that countries should specialize in the production and export of goods and services in which they have a relative efficiency advantage, even if one country is more efficient in producing all goods. By focusing on comparative instead of absolute advantages, countries can trade to mutual benefit, leading to increased total output, resource efficiency, and economic welfare. Comparative Advantage Theory states that countries benefit by specializing in and exporting goods they can produce relatively more efficiently than others, thereby maximizing global output and mutual economic gains through trade.

Over time, the theory has been expanded and refined. Modern interpretations link comparative advantage with factors such as labor productivity, technology, and institutional quality. In dynamic trade models, comparative advantage evolves with human capital accumulation, innovation, and policy choices. Export activity, in this context, reflects a country’s underlying comparative strengths and contributes to growth through reallocation of resources to higher-productivity sectors.

Empirical studies have demonstrated that export specialization based on comparative advantage is associated with faster GDP growth, improved employment structures, and higher total factor productivity. Therefore, this theory provides a strong foundation for examining how education and human capital can shape a country's export structure and trade competitiveness, ultimately influencing long-term economic growth.

2.2. Relation between education and exports

The relation between education and exports is given equal attention and there are classic theories have revealed the causal logic between them.

Human Capital Theory posits that individuals’ education, skills, and health are forms of capital that enhance their productivity and, in turn, contribute to economic growth. Originally developed by economists such as Theodore Schultz and Gary Becker in the 1960s, the theory emphasizes that investments in human capital—particularly through formal education and training—lead to higher earnings for individuals and greater efficiency for economies. Education improves workers' cognitive abilities, adaptability, and innovative capacity, which ultimately boosts firm productivity and national competitiveness.

From a macroeconomic perspective, countries with higher levels of human capital are more likely to experience sustained economic growth, structural transformation, and successful integration into global markets. In the context of international trade, human capital plays a critical role in enabling economies to move up the value chain, produce more sophisticated export goods, and absorb foreign technologies through learning and innovation.

Therefore, Human Capital Theory provides a conceptual basis for understanding how education influences export performance. In particular, it supports the hypothesis that improved education leads to a more skilled labor force, which enhances a country’s comparative advantage and export capacity, ultimately contributing to long-term economic development.

New Growth Theory also asserts education can improve exports, and ultimately, boost the economy. However, there are a few different distinctions like the mechanism through which education can stimulate exports. While Human Capital Theory emphasizes how education improves individual productivity and labor efficiency—thereby enhancing export capacity, New Growth Theory extends this view by focusing on how education fosters innovation, knowledge accumulation, and technology diffusion, which are critical for sustaining long-term export competitiveness and economic growth in an open economy [13].

2.3. Research gaps

The current studies have concentrated on the relations among education, exports, and economic development. There are different theories argues that education can impose an effect through different channels, such as through uplifting individual productivity and labor efficiency, which is a complete economic channel; and through fostering innovation and ultimately, changing the export structure.

However, there is still a lack in quantified methods and proof of how education can affect exports. In other words, the mediation analysis about through what channel education affects exports remains blank. The purpose of this paper, is to provide an insight on how significant education affects exports through changing an economy’s export structure via a quantified method.

2.4. Research contribution

This study has not only been a supplement to the current theories but also provided insights into practice. Traditional international trade theories primarily focus on resource endowments and comparative advantages, with education often simplified as labor quantity [14]. This study expands the theoretical scope of education's impact on foreign trade by introducing the human capital mechanism, revealing how education quality and skill enhancement indirectly promote exports. This article aims to fill in the blank by concentrating on one mediator, export complexity, to understand how this mediator bridge tertiary education and exports.

Directly managing exports does not seem practicable for there are quite a number of variables jointly influencing exports. Trade and exports are affected by both domestic and foreign factors that cannot be easily managed. In contrast, education is a more controllable factor which can be drastically prioritized by domestic governments. By thorough understanding how education influences exports through changing the export structure, it can be more practical for policy makers to drive exports with the education leverage.

3. Methodology and model

In order to decompose the interrelation between tertiary education and export performance, a mediation analysis is necessary. The core idea of carrying out mediation analysis for consecutive variables is to utilize linear regression. Comparing different coefficients in the linear regression models can provide the insights on how close the relations are to each other. For consecutive variables, the linear regression part is the same. There is only a minor difference lying in the interpretation of regression model coefficients when adopting different approaches, e.g. Causal Steps Regression and Bootstrap method.

3.1. Variable selection

As for the variables for the research, the main steps of this research include checking the total effect of

3.2. Mediation analysis modeling

The nature of using linear regression to perform mediation analysis is about measuring the correlation between different variables by repetitive usage of linear regression. The overall steps can be concluded in the following equations followed by explanation on each.

For the letters in the equations above,

As for interpretation of Casual steps regression, we will combine all the previous regression results. In equation (1), the first thing is to check if the coefficient

Given the coefficient c is significant, the next step is about looking into the coefficients a and b in equation (2). Different combinations of coefficients a and b, in this approach, suggest 2 scenarios. One scenario happens when both coefficients turn out to be significant. In which case, the estimation turns to focusing on the coefficient c’. And when look at coefficient c’ for its statistical significance, the overall conclusion will be either the mediation effect is realized by full mediation through the mediator variable, or the mediation effect is only partial mediation. The other scenario happens when both shows to be insignificant, in which case a Sobel test is needed to determine the validity of mediation effect.

3.3. Robustness test

Robustness check is comprehensively used in mediation analysis to strengthen the conclusion by eliminating misled conclusion due to sample distribution and variable selection. This session will talk about the necessity and practical steps of robustness checks.

3.3.1. The underlying logic of robustness test

The conclusion drawn solely by the Causal Steps Regression method is not reliable all the time. There are multiple advantages explain why a robustness test is necessary: avoiding wrong conclusion drawn due to assumptive data distribution, reinforced conclusion by various methods, quantifying potential bias influence due to unmeasured variables, and strengthened result by placing with different variables or practicing with alternative model specifications (e.g., adding control variables or applying nonlinear models).

For this article in particular, the causal steps regression method proposed by Baron and Kenny does not directly test the statistical significance of the indirect effect i.e., the product of path coefficients [15]. Since this product term typically violates the normality assumption, the commonly used Sobel test may lack statistical power, especially in small samples or when data are skewed. To address this limitation and enhance the robustness of the mediation analysis, this study applies the non-parametric Bootstrap method to estimate confidence intervals for the indirect effect. The Bootstrap approach does not rely on distributional assumptions and is widely recognized as one of the most reliable and powerful methods for testing mediation effects in empirical research.

3.3.2. Robustness test method selection

To assess the robustness of the mediation effect, we employed a nonparametric bootstrap approach using the mediate function from the R mediation package. Specifically, we first estimated the mediator model (predicting the mediator from the independent variable) and the outcome model (predicting the dependent variable from both the independent variable and the mediator). We then conducted causal mediation analysis with 5,000 bootstrap simulations to obtain robust estimates of the average causal mediation effect (ACME), average direct effect (ADE), total effect, and the proportion mediated. The bootstrap method provides percentile-based confidence intervals that are less sensitive to violations of normality and small-sample biases, offering a more reliable inference than traditional methods such as the Sobel test. The consistency and statistical significance of the ACME across bootstrap samples confirm the robustness of the identified mediation effect

4. Results

This chapter covers the results of the whole mediation analysis, from the total effect model, to mediation model, and to direct effect model. The regression results of each model are put in separate sessions respectively.

4.1. Linear regression results

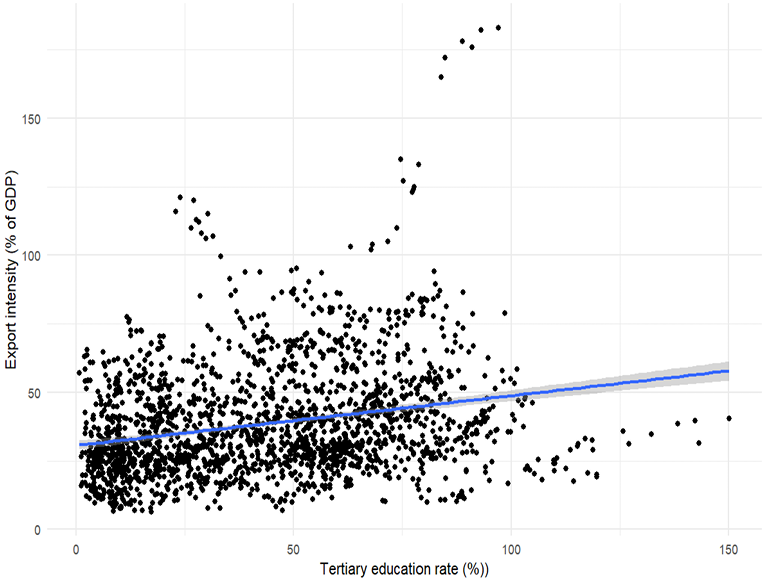

The purpose of this total effect validation as mentioned before is about to prove there exists a clear influence from X to Y. This step lays the theoretical foundation for further steps of a mediation analysis. The following graph is a standard linear regression model plotted by the R language.

As shown in Figure 1, despite a few outliners, the plot in the graph still indicates a linear correlation between the tertiary education rate

Table 1 below shows the linear regression results between

|

Linear regression statistics |

Value |

|

-Regression coefficient: x |

0.181 |

|

-p-value, t-statistic |

<0.01 |

|

Std. Error: coefficient |

0.016 |

|

Constant |

30.666 |

|

p-value, t-statistic |

<0.01 |

|

Std. Error: constant |

0.838 |

|

Observations |

2025 |

|

R2 |

0.058 |

|

Adjusted R2 |

0.058 |

|

Residual Std. Error |

20.139 (df=2023) |

|

F Statistic |

125.215 (df=1; 2023) |

|

p-value, F-statistic |

<0.01 |

4.2. Mediation analysis results

Based on the confirmed positive correlation between X and Y, we next carry on the Mediation analysis using involving all 3 factors. The following Table 2 comprises 2 models: one shows the influence that X exerts on M; the other is the combined influence X imposes on Y, through direct and mediated paths.

|

Linear regression statistics |

Value (Mediator model regression, M~X) |

Value (Direct effect model regression, Y~X+M) |

|

Regression coefficient: X |

0.024 |

0.042 |

|

p-value, t-statistic |

<0.01 |

0.071 |

|

Std. Error: coefficient |

0.001 |

0.023 |

|

Regression coefficient: M |

5.742 |

|

|

p-value, t-statistic |

<0.01 |

|

|

Std. Error: coefficient |

0.686 |

|

|

Constant |

-0.920 |

35.946 |

|

p-value, t-statistic |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

|

Std. Error: coefficient |

0.027 |

1.038 |

|

Observations |

2025 |

2025 |

|

R2 |

0.523 |

0.090 |

|

Adjusted R2 |

0.523 |

0.089 |

|

Residual Std. Error |

0.642 (df=2023) |

19.804 (df=2022) |

|

F-statistic |

2217.943(df=1; 2023) |

99.744(df=2; 2022) |

|

p-value, F-statistic |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

As regards the mediated effect model, the regression coefficient turns out to be 0.024 meaning every 1% increase in tertiary education rate can possibly lead to 2.4% increase in Export complexity index. In addition, this coefficient is proved to be statistically significant (p<0.01). Education, especially tertiary education is proved to contribute to more than half of the change in export complexity (

Table 2 above also reveals the results of the direct effect linear regression model of

The mediated effect model presents to be significant and explanatory (p-value: F statistic <0.01), indicating there is a valid correlation between

With all the linear regression results, the following mediation model coefficient table can be drawn.

|

Coefficient |

Model/Path |

p-value |

Statistically significant? |

|

Mediation effect model |

<0.01 |

Yes |

|

|

Meditation effect model |

<0.01 |

Yes |

|

|

Total effect model |

<0.01 |

Yes |

|

|

Direct effect model |

0.071 |

No |

As showing Table 3, According to the causal step regression approach, if coefficients a, b, and c are all statistically significant while c' is insignificant when the mediator is independently considered, then this pattern indicates that it is a fully mediated effect through the export complexity index.

4.3. Robustness test results

To ensure the reliability of conclusion drawn from Causal steps regression, Table 4 is the robust test result with Bootstrap method. In particular, Bootstrap can fill in the blank of significance test of mediated effect,

|

Mediation effect |

Estimate |

95% CI lower |

95% CI upper |

p-value |

|

ACME (Average causal mediation effect) |

0.1395 |

0.1066 |

0.1724 |

<0.001 |

|

ADE (Average direct effect) |

0.0417 |

0.0007 |

0.0850 |

0.0476 |

|

Total effect |

0.1812 |

0.1471 |

0.2169 |

<0.001 |

|

Proportion mediated |

0.7699 |

0.5765 |

0.9957 |

<0.001 |

Bootstrap approach reveals a similar conclusion with a small distinction. This method also suggests there exists a strong mediated effect like the causal steps regression approach does. Nonetheless, it points out that the direct effect still remains significant and cannot be overlooked. Besides, Bootstrap suggests a proportion mediated effect of 77%.

5. Further discussion

This chapter wraps up the primary findings of this research so as to give highlight on the insights. Moreover, based on the conclusion, a few policy making suggestions are also rendered in the hope of resolving real life challenges especially for developing countries.

5.1. Primary research findings

There is a positive and strong correlation between tertiary education and export intensity, meaning education is a confirmed contributor to exports (p-value significant <0.01). On the other hand, education is clearly not the only one drive for export intensity as education in this model only seem to explain 5.8% of the variance of the change in export intensity (

Bootstrap approach and Causal steps regression method gives different conclusions on if export structure should be full mediation or partial mediation. Causal steps regression sees this as full mediation as the direct effect presents to be insignificant (

5.2. Extensions on existing theories

A number of theories have stated that education can boost exports and GDP through different channels, such as uplifting individual productivity and fostering innovation. But the majority did not quantify the influences from different channels and leave the subjects incomparable.

This research reveals the logical chain from tertiary education to export structure and, ultimately to export intensity with statistical grounds. We confirm that education is a clear but not dominant driving force for exports intensity, and the limited influence originated from education advantage is primarily passed down by raising the complexity in export structure.

5.3. Insights into policy making

This study sheds light on the mechanism through which education contributes to export growth by enhancing the quality of human capital, offering significant implications for public policy. The findings suggest that education is not only a foundation for human development but also a strategic driver of export competitiveness. For policymakers, this underscores the importance of investing in higher education and vocational training, to strengthen a country’s position in global trade. Moreover, the identified mediator of export structure suggests that diversity in higher education disciplines is one prerequisite to foster a coherent education–skills–exports pathway which ultimately supporting long-term, sustainable economic growth.

6. Conclusion

This study intends to figure out the interrelation among higher education, export structure, and export intensity on a global scale. Selecting higher education enrollment rate, ECI, and export intensity as the key variables, a mediation analysis is introduced to quantify the effect of higher education on export intensity through export structure as a mediator. The initial conclusion that exports structure plays full mediation is drawn by Causal step regressions approach, which later is modified into partial mediation by introducing Bootstrap method for a robustness test. Further research based on this study can test with other variables. Other education indicators such as tertiary education graduation rate, doctorate percentage of the popularity, are also worth consideration. Such replacement of variables is similarly meaningful for export-related variable selection. Apart from variable replacement, future study may try to focus on a longer period and to segment countries into different groups. Pre-grouping countries prior to analysis allows for better control of regional heterogeneity.

References

[1]. Mamadouh, V. (2023). Geography and war, geographers and peace: Expanding research and political agendas. Making geographies of peace and conflict, 12-36.

[2]. Ali, A., Fatima, N., Rahman Ali, B. J. A., & Husain, F. (2023). Imports, Exports and Growth of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)-A Relational Variability Analysis. International Journal of Sustainable Development & Planning, 18(6).

[3]. Jia, Z., Wang, Y., Chen, Y., & Chen, Y. (2022). The role of trade liberalization in promoting regional integration and sustainability: The case of regional comprehensive economic partnership. Plos one, 17(11). 2

[4]. Odhiambo, N. M. (2022). Is export-led growth hypothesis still valid for sub-Saharan African countries? New evidence from panel data analysis. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 31(1), 77-93.

[5]. Anyanwu, J. C., & Salami, A. O. (2021). The impact of COVID‐19 on African economies: An introduction. African Development Review, 33(Suppl 1), S1.

[6]. Kumar, S., Shahid, A., & Agarwal, M. (2024). Is BRICS expansion significant for global trade and GDP?. BRICS Journal of Economics, 5(4), 5-36.

[7]. Udeagha, M. C., & Ngepah, N. (2023). Towards climate action and UN sustainable development goals in BRICS economies: do export diversification, fiscal decentralisation and environmental innovation matter?. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 15(1), 172-200.

[8]. Mankiw, N. G. (2021). Principles of economics. http: //thuvienso.thanglong.edu.vn/handle/TLU/11469

[9]. Dosi, G., & Tranchero, M. (2021). The role of comparative advantage, endowments, and technology in structural transformation. New perspectives on structural change: causes and consequences of structural change in the global economy, 442-474.

[10]. Mulliqi, A. (2021). The role of education in explaining technology-intensive exports: A comparative analysis of transition and non-transition economies. Eastern Journal of European Studies, 12(1), 141–172.

[11]. Hossain, J. Exploring the Role of Exports in Economic Growth: A Panel Study Across Diverse Income Economies.

[12]. Reed, T. (2024). Export-led industrial policy for developing countries: Is there a way to pick winners?. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 38(4), 3-26.

[13]. Tran, H. T., Santarelli, E., & Wei, W. X. (2022). Open innovation knowledge management in transition to market economy: Integrating dynamic capability and institutional theory. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 31(7), 575-603.

[14]. Reyes-Heroles, R. (2018). Globalization and structural change in the united states: A quantitative assessment. In 2018 Meeting Papers (Vol. 1027). Society for Economic Dynamics.

[15]. World Bank. (2020). World Development Report 2020: Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains. Washington, DC: World Bank. https: //doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1457-0

Cite this article

Zou,S. (2025). Exporting Through Complexity: The Indirect Influence of Higher Education on Export Intensity. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,211,61-72.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICEMGD 2025 Symposium: Resilient Business Strategies in Global Markets

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Mamadouh, V. (2023). Geography and war, geographers and peace: Expanding research and political agendas. Making geographies of peace and conflict, 12-36.

[2]. Ali, A., Fatima, N., Rahman Ali, B. J. A., & Husain, F. (2023). Imports, Exports and Growth of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)-A Relational Variability Analysis. International Journal of Sustainable Development & Planning, 18(6).

[3]. Jia, Z., Wang, Y., Chen, Y., & Chen, Y. (2022). The role of trade liberalization in promoting regional integration and sustainability: The case of regional comprehensive economic partnership. Plos one, 17(11). 2

[4]. Odhiambo, N. M. (2022). Is export-led growth hypothesis still valid for sub-Saharan African countries? New evidence from panel data analysis. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 31(1), 77-93.

[5]. Anyanwu, J. C., & Salami, A. O. (2021). The impact of COVID‐19 on African economies: An introduction. African Development Review, 33(Suppl 1), S1.

[6]. Kumar, S., Shahid, A., & Agarwal, M. (2024). Is BRICS expansion significant for global trade and GDP?. BRICS Journal of Economics, 5(4), 5-36.

[7]. Udeagha, M. C., & Ngepah, N. (2023). Towards climate action and UN sustainable development goals in BRICS economies: do export diversification, fiscal decentralisation and environmental innovation matter?. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 15(1), 172-200.

[8]. Mankiw, N. G. (2021). Principles of economics. http: //thuvienso.thanglong.edu.vn/handle/TLU/11469

[9]. Dosi, G., & Tranchero, M. (2021). The role of comparative advantage, endowments, and technology in structural transformation. New perspectives on structural change: causes and consequences of structural change in the global economy, 442-474.

[10]. Mulliqi, A. (2021). The role of education in explaining technology-intensive exports: A comparative analysis of transition and non-transition economies. Eastern Journal of European Studies, 12(1), 141–172.

[11]. Hossain, J. Exploring the Role of Exports in Economic Growth: A Panel Study Across Diverse Income Economies.

[12]. Reed, T. (2024). Export-led industrial policy for developing countries: Is there a way to pick winners?. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 38(4), 3-26.

[13]. Tran, H. T., Santarelli, E., & Wei, W. X. (2022). Open innovation knowledge management in transition to market economy: Integrating dynamic capability and institutional theory. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 31(7), 575-603.

[14]. Reyes-Heroles, R. (2018). Globalization and structural change in the united states: A quantitative assessment. In 2018 Meeting Papers (Vol. 1027). Society for Economic Dynamics.

[15]. World Bank. (2020). World Development Report 2020: Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains. Washington, DC: World Bank. https: //doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1457-0