1. Introduction

In the era of rapid digitalization, social media has become an integral part of daily life, with billions of users worldwide. In early 2023, China had over 1.05 billion internet users, with 1.03 billion actively engaging on social media, representing 73.7% and 72% of the population, respectively [1,2]. However, the widespread use of social media has also brought to light the troubling phenomenon of online stigmatization. Individuals, particularly women, who engage in activities traditionally deemed unconventional, such as sports, are often subject to severe stigmatization [3]. This issue is particularly pronounced among Chinese youth, including Generation Z, who are not only active on social media but also highly susceptible to its psychological impacts. Therefore, this study is vital as it explores the underlying factors of online stigmatization, particularly affecting Chinese women in non-traditional activities like sports, within the pervasive social media landscape.

Studies have shown that social media stigmatization can have traumatic effects, especially on young people. The constant exposure to negative comments and stereotypes can lead to serious psychological consequences, including anxiety, depression, and a decrease in self-esteem. Despite the growing awareness of these issues, there is a significant gap in research, particularly in examining the formation and propagation of gender-based sports stigmatization among Gen Z females on social media, Therefore, this study seeks to explore stigmatization from the Gen Z perspective, as they represent the future of consumer power in China. Understanding their experiences and perceptions is crucial for effectively combating stigmatization and promoting the de-stigmatization of golf in China.

This study examines gender-based sports stigmatization by analyzing 22,354 comments tagged with "golf yuan" on Xiaohongshu using grounded theory. The goal is to develop a theoretical model that explains the stigmatization of women in sports, particularly golf, and its impact on public opinion. NVivo software was used to systematically extract categories from the data.

2. Literature review

2.1. Stigmatization theory development: a summary

The concept of stigma has been extensively theorized and researched across various disciplines, particularly in sociology and psychology. The initial theoretical foundation was laid by Erving Goffman in 1963, who defined stigma as an "attribute that is deeply discrediting." [4] Goffman's work highlighted the social construction of stigma and the ways in which individuals move between more or less stigmatized categories depending on their knowledge and disclosure of their stigmatizing condition [5].

Based on their studies, Link and Phelan introduced a conceptual model for the stigma process which specifies four important elements in this context including labelling, stereotyping, separation and status loss & discrimination [6]. The focus in that model was on power and its connection to the social inequalities involved in stigmatizing.

In recent years, social psycholo- gists have created a series of theories to account for the ways in which stigma may operate at various levels: public stigma (also called enacted or institutionalized stigmatization), self-stigma and associative, structural forms of stigmaareas where Dominance theory has logical implications as well [7,8]. For example, attribution theory describes how the public attributes bipolar disorder to specific characteristics of its sufferers and thereby exerts different levels of stigma. The social-cognitive model, on the other hand proposes that internalized stigma develops via awareness (of societal beliefs about a stigmatized identity), agreement (with those societal perceptions of one’s group), application(apply these stereotypes to self), and harm(recognize harm caused by applying stereotype) [9].

In addition, researchers have identified the importance of multi-level frameworks to conceptualize stigma complexity such as Mental Illness Stigma Framework and Health/illness-Stigma Discrimination framework. These approaches focus on how individual, interpersonal, community and societal factors intersect to influence stigmatization [10].

While the concept of stigmatization is still evolving, researchers have begun to examine novel perspectives (e.g. religiocultural and structural violence approaches) that can further delineate and broaden this theory in an increasingly complex field [11]. Theories like these have been central to deciphering the reasons for and consequences of stigma as well its reduction in different contexts.

2.2. Factors contributing to stigmatization and the mechanism behind it

Scholars have pinpointed a variety of factors that contribute to the process of stigmatization. Public perceptions and beliefs about mental and substance use disorders are influenced by knowledge about these disorders, contact with affected individuals, media portrayals, and social norms concerning cause and perceived dangerousness. Race, ethnicity, and culture also play a role in shaping stigmatizing attitudes [12].

The stigmatization process occurs at multiple levels. At the individual level, anticipated stigma refers to expecting discrimination, enacted stigma refers to experiencing past discrimination, and internalized stigma refers to feeling shame or self-loathing. At the interpersonal level, stigma mechanisms include dyadic social interactions, social network homogeneity, and social support. At the sociocultural level, stigma influences hazardous environmental exposures, health care access and quality, and public policy [13].

More recently, researchers have proposed multi-level frameworks like the Mental Illness Stigma Framework and the Health and Stigma Discrimination Framework to capture the complex interplay between individual, interpersonal, community, and societal factors in shaping stigmatization experiences [14,15]. Integrating time into stigma research has also emerged as an important approach to understand how stigma evolves over historical, developmental, and status course timescales [16].

2.3. Gender-based sports stigmatization: a summary

The study of gender-based sports stigmatization has evolved significantly, beginning with early feminist critiques of sports as a domain dominated by masculine ideals. Initial theories, such as those proposed by Goffman, highlighted how stigma arises from societal expectations and stereotypes, particularly regarding femininity and athleticism. Early research indicated that female athletes faced stereotypes portraying them as less capable and more focused on appearance than performance.

Significant milestones include the enactment of Title IX in the United States in 1972, which aimed to promote gender equity in sports, leading to increased participation of women. Unfortunately, new research finds that even in 2015, women athletes competing in conventionally male sports are still judged to be abnormal, if not outright un-womanly. Recent research has explored the mechanisms through which being stigmatized impacts female athletes and has employed a combination of both quantitative (9, 15) as well as qualitative approaches, indicating that implicit and explicit prejudices continue to be connected with perceptions by members of the public in relationship to what it means for females pursue sports.

Intersectionality, in the most recent iterations of these models, attention has broadened to include intersectionalities among race, class and sexuality as potential moderators that intensify stigmatization responses. Social Identity Theory and Gender Role Theory are often used to examine how acceptance of social norms can influence the process of stigmatization. More recently, scholars have called for a more nuanced perspective of these dynamics that emphasizes the relational dimensions of stigma and how media portrayals might influence female athletes' self-acceptance or acceptance by society. This evolving knowledge further highlights the necessity of continuous work for gender equity in sports.

3. Research design

3.1. Research method

The grounded theory method applies to this study by collecting posts and comments across social media on “Golf Yuan”. We ultimately extracted meaningful sub- and main categories of the text data using NVivo software, which enabled a systematic comprehension of mechanisms studied in the category FORMATION OF STIGMATIZATION; in addition to influences examined within stigmatization.

3.2. Data collection

This study analyzes discussions about "golf girls" on the Xiaohongshu platform, targeting the period from July 16, 2020, to July 27, 2024. According to official data, Xiaohongshu's user base exceeds 300 million. As a rapidly growing platform in recent years, its content and user interaction data are more representative, making it suitable as a research sample [17]. A web crawler tool was used to retrieve original posts containing the keyword "Golf Yuan" on Xiaohongshu, resulting in 998 original posts and 22,354 comments. All data in this study are based on publicly available texts from Xiaohongshu and do not involve any personal user privacy.

3.3. Data processing

This study uses Python software to clean all collected comments, including:

1)Removing texts containing only emoji or other non-meaningful content.

2)Checking for and deleting duplicate texts to ensure data uniqueness.

The final dataset comprises 5,051 valid comments, totaling 99,435 words. Of these, 4,800 comments were selected for category extraction and relationship construction, and 200 comments were used for theoretical saturation testing.

4. Category extraction and relationship construction

4.1. Open coding

Open coding involves analyzing the collected data word by word, breaking down the data, assigning concepts, and initially categorizing these concepts [18]. During the open coding phase, this study imported 5,000 Xiaohongshu texts into NVivo 14. Through repeated comparisons of the texts, 24 initial concepts and 12 categories were ultimately identified (Table 1).

|

Categories |

Initial Concepts |

Original Sentences |

|

Negative Emotion |

Questioning |

Isn't it better to just watch a video to see how well they play? |

|

Devaluation |

There are many "Yuan" and they all claim that they have plenty of money. None of them likes to pay the bill themselves. They even wait for others to tip and say it's to give the guys face. |

|

|

Positive emotion |

Sympathy |

The figure is great. Why are there so many malicious remarks for this which is not overly revealing? |

|

Appreciation |

I saw the vlog of the little beauty participating in the competition. I followed it and liked it very much. Her posture is elegant, her mood is stable, and she has a strong core. I really like watching you chip the ball. Enjoy golf. It's a whole life sport. |

|

|

Stereotypes |

Golf Stigmatization |

I think golf is a sport for the rich. |

|

Stigma Resistance Independent Self-Awareness |

Denial of Stigma Condemnation of Stigma Self-Expression |

Golf skirts are designed for convenience of movement and they all have built-in pants inside. I don't understand what some people are trying to pry into. The best solution is not to prove whether you are a "Yuan" or not. When you reach your level and realm, no one can consider you a "Yuan". For those who haven't experienced or seen much, or are still at a lower level or just hanging around in the practice range and evaluating others as "Yuan" or not, you don't need to care at all. After all, who would explain advanced mathematics problems to primary school students? I started playing golf initially because I was in a slump during that period. Since getting involved with golf and going to the training ground every day, I began to care about my appearance, ponder over outfits and dress up a little. Anything that is beneficial to physical and mental pleasure should be pursued without caring about others' opinions and persisted in well. |

|

Ignoring Comments |

No one can control others' mouths, but one can control one's own behavior. Just be happy yourself. I can't control cognitive biases either. |

|

|

Interactive Contradictions Behavioral Motivation Labeling Cultural Dynamics and Evolution Social Atmosphere External Bias Behavioral Performance |

Cognitive Dissonance Discourse Conflict Sense of Superiority Peer Comparison Conceptual Labeling Cultural Concepts Evolution of Meaning Pretended Preferences False Trends Behavioral Characteristics Clothing Characteristics Physical Appearance Characteristics Image Comparison Avoidance Behavior Body Language |

I think golf is a sport that requires skills and concentration. However, some people always confuse the fashionable outfits of female golfers with the scenes on the golf course, believing that it's for attracting attention. They have to wipe (the lens), take overhead shots, and then say, "Oh, I'm not. It's a normal shot. I'm wearing leggings." Are you a "Yuan" or not? How do you like to take photos? How many sets of clothes? I don't care, but just don't hinder my progress in playing golf. Having afternoon tea is said to be "group-buying Yuan", playing frisbee is said to be "frisbee Yuan", and playing golf is said to be "golf Yuan". A girl with a bit of good looks playing golf is just a "golf Yuan", isn't she? I don't know why one dresses like this to play golf... They haven't even figured out the most basic etiquette of what to wear where. Or do they simply not care that much about this sport? Originally, "Yuan" is a very good character. It's just been stigmatized. This clearly shows that one doesn't exercise regularly. It's deliberately done for the video just to create an effect. A girl spent her life savings learning golf, yoga, equestrian and other programs in order to marry into a wealthy family. She did get to know some second-generation rich people. Unfortunately, she didn't enter the wealthy family and was slept with by five people for free five times. Could the posture be any more fake? Many "golf Yuan" have such short skirts that their butts are exposed... They really dare to go all out. Applying such heavy makeup to do sports and then claiming not to be a "Yuan"...??? Normally, who would put on makeup just to do sports? I, who look all dusty and disheveled when practicing golf, really envy those young ladies who can take great photos. I'd rather stay away from those women who play golf. This hobby really disgusts me. Looking at you women playing golf makes me so angry. I really want to rush up and teach you a lesson! |

4.2. Axial coding

Axial coding aims to further classify and organize the initial concepts obtained from open coding to extract main categories. In this study, the 12 initial categories were condensed into 7 main categories (Table 2).

|

Main category |

Subcategory |

Category content |

|

Emotional dimension |

Negative emotion |

It refers to the emotions such as doubt and disparagement that stigmatizers have towards the stigmatized. |

|

Positive emotion |

It refers to the emotions such as sympathy and appreciation that stigmatizers have towards the stigmatized. |

|

|

Social environment |

Social atmosphere |

It refers to the prevalent cultural atmosphere or behavioral hobbies. |

|

Escalation of discourse |

Interactive contradictions |

It refers to the mutually conflicting or contradictory words that occur in the communication process. |

|

Behavioral motivation |

It refers to the motivation of the stigmatizer to show themselves or attract others' attention through behavior or words. |

|

|

Resistance behavior |

Stigma Resistance |

The resistance behaviors such as denial and condemnation of the stigmatized individuals after being stigmatized |

|

Behavioral dimension Cultural factors Cognitive dimension |

Independent Self-Awareness Behavioral motivation Labeling Cultural Dynamics and Evolution Stereotypes External Bias |

It refers to the autonomous decision-making of the stigmatized individuals in their thinking and actions, reflecting the self-dominance that does not rely on others or external influences. It refers to the specific behaviors and manners displayed by the stigmatizer in a particular situation. It refers to the act of the stigmatizer affixing specific labels to the stigmatized individuals. It refers to the process by which culture gradually changes and develops in society over time. It refers to the fixed and simplified views or perceptions that the stigmatizer holds towards a certain group or individual. It refers to the negative impressions that the stigmatizer holds towards the stigmatized individuals based on external characteristics such as appearance and behavior. |

4.3. Selective coding

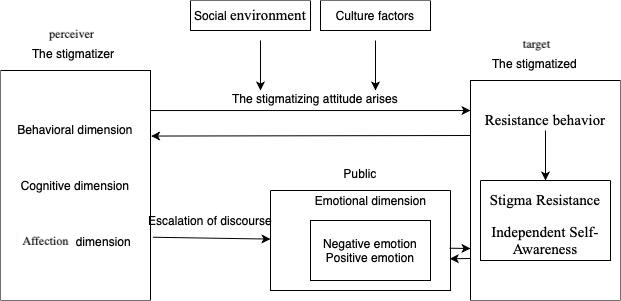

Selective coding aims to establish a systematic theoretical framework by organically integrating the extracted main categories to form a complete theoretical model (Table 3). Specifically, the behavioral and cognitive dimensions are the internal driving factors of the stigmatization of the frisbee sport, while social environment, escalation of discourse, and cultural factors are the external driving factors. Emotional tendencies act as a mediating factor between the stigmatizers and the stigmatized. Ultimately, this theoretical model elucidates the influencing factors of sports stigmatization in the context of big data (Figure 1).

|

Functional path |

Relational structure |

Connotation of the path |

|

Behavioral dimension- The stigmatization of golf sports |

Internal drivers |

The behavioral dimension is an internal driving factor for the stigmatization of golf. The stigmatizers directly promote the formation of stigmatizing attitudes through behavioral motivation and label assignment. |

|

Cognitive dimension- The stigmatization of golf sports |

Internal drivers |

The cognitive dimension is an internal driving factor for the stigmatization of golf. The stereotypes and external biases of the stigmatizers themselves promote the formation of stigmatizing attitudes. |

|

Emotional dimension- The stigmatization of golf sports |

Internal drivers/ Intermediary factor |

Emotional dimension is both an internal driving factor and a mediating factor for the stigmatization of golf. That is, the stigmatizers have negative emotions, thereby generating stigmatizing attitudes. At the same time, the stigmatizers will influence the emotions of individuals in society, thereby triggering stigmatization of specific targets. |

|

The stigmatization of golf sports- Resistance behavior |

Internal drivers |

The stigmatization of golf directly affects the resistance behaviors of the stigmatized individuals, thereby leading to the emergence of their independent self-awareness and behaviors against stigmatization. |

|

Escalation of discourse- The stigmatization of golf sports |

External driver |

The behavior pattern of the stigmatizers intensifying through words can affect the emotions of individuals in society, thereby triggering stigmatization of specific targets. |

|

Social environment- The stigmatization of golf sports Cultural factors- The stigmatization of golf sports |

External driver External driver |

The behavioral dimension, cognitive dimension and emotional dimension can have an impact on the stigmatization of golf, and this impact is externally driven by social environmental factors. The behavioral dimension, cognitive dimension and emotional dimension can have an impact on the stigmatization of golf, and this impact is externally driven by culture factors. |

4.4. Theoretical saturation test

To ensure the reliability and validity of the study, a theoretical saturation test was conducted on the 200 texts reserved in the preliminary stage. During the analysis process, the repetition and consistency of the data were observed. It was found that the new data did not provide any new concepts or categories, indicating that the concepts proposed in this study had reached theoretical saturation.

5. Results

5.1. The stigmalizaer analysis -psychological perspective

Scholar Guan Jian posits that the formation of stigmatizing attitudes is underpinned by the interaction of three fundamental components: affection, behavior, and cognition. These elements do not operate in isolation but rather engage in a dynamic interplay, giving rise to a complex stigmatization system [19].

The relationship between the affection and cognitive dimensions of stigmatization is significantly influenced by cultural and societal factors. Traditional Chinese culture has long held that women should primarily focus on domestic responsibilities, such as being housewives and raising children. This cultural norm creates an intuitive reaction—rooted in what Daniel Kahneman refers to as "System 1" thinking—where men, upon encountering images of women displaying strength and beauty, may instinctively feel discomfort or dislike. This reaction is almost an automatic one, driven by cultural expectations and biases [5].

Golf has been further stigmatized in China as a sport for many years, hence making the situation more complex. A number of political, economic, social and technological factors have contributed to the stigma surrounding golf in China. They include government policies and anti-corruption campaigns that influenced public perception of this sport; economic exclusivity as well as cultural disconnect with mainstream understanding which marginalised it even more; environmental concerns and low uptake of sustainability practices that all negatively impact on how Chinese people understand golf.

This intersection of cultural norms and the golf stigma causes a higher degree of emotions as can be seen above. An image of a strong woman in golf, which is already stigmatized, makes the discomfort even more pronounced amongst onlookers. In turn, these heightened emotions then impact System 2 thinking or cognitive dimension making individuals more prone to cognitive biases. Such prejudices influenced by societal and anthropological forces result into misinterpretation and negative opinions about women who break from traditional roles and succeed in stigmatized fields such as golf.

Therefore, the emotional aspect rooted in instinctive aversion powers cognitive biases that will later be evident as stigmatic comments under posts made by women playing golf. This cycle highlights how complicated it is for prejudiced attitudes to develop due to interactions between cultural norms, emotions and cognition.

For example, a netizen commented, "Am I the only one who thinks that her dress combined with her repetitive movements look more and more ridiculous and have no aesthetic feeling at all? Moreover, for such an elegant sport, how come I only see violence from her? Is this the so-called excessive force in all aspects?"

5.2. Social media analysis - media studies perspective

Media research monitor that social media plays a significant function in molding public perceptions and narratives round gender in sports activities. The particularly anonymous and disinhibited nature of social media structures is essential to the spreading of stigmatizing discourse. Anonymity permits individuals to make stigmatizing or discriminatory feedback with much less worry of punishment, which has led to an increase in gender-primarily based harassment and stigmatization [20]. This hassle is compounded by means of methods wherein gender and gender-related issues are portrayed at the said structures. There are severa methods advantageous and diverse portrayals of marginalized classes like LGBTQ can mission biases and reduce stigma. Conversely, bad or stereotypical representations can strengthen harmful prejudices main to the perpetuation and dissemination of stigma.

The trouble is in addition compounded with the aid of the impact social constructs and network norms within precise on-line communities have on it. In communities upholding strict heteronormative values, there's an inclination for members who defy those norms to be stigmatized, which includes the Fujoshi community, who're regarded negatively for his or her hobby in homoerotic content material. Thus emphasizing the significance on-line subcultures play in perpetuating gender-based totally stigmatization [21].

Additionally, social media algorithms, which prioritize content that generates excessive engagement—frequently divisive or sensational—make contributions to the amplification of negative stereotypes and stigmatizing content material. This algorithmic amplification creates an "records cocoon," in which customers are much more likely to encounter and have interaction with divisive content, consisting of that which boosts gender stereotypes. As these new social media norms become entrenched, the algorithms preserve to boost and propagate stigmatization, making it even extra pervasive and challenging to counteract [22].

For example, “A girl spent her life savings learning golf, yoga, equestrian and other programs in order to marry into a wealthy family. She did get to know some second-generation rich people. Unfortunately, she didn't enter the wealthy family and was slept with by five people for free five times.” from our false trend data shown.

This study reveals that the widespread adoption of such stigmatizing discourse styles on social media not only reflects individual psychological states but also profoundly shapes social public opinion and values. The interplay of anonymity, representation, social constructs, and algorithmic amplification creates a feedback loop that perpetuates and deepens stigmatization, particularly gender-based biases, in the digital age.

5.3. Social environment and culture factors analysis - sociological and gender studies perspective

From a sociological and gender studies viewpoint, social media often perpetuates traditional gender norms and ideologies. Women athletes, particularly in strength sports, face significant online abuse and gender-based violence. This abuse often manifests through "Virtual Manhood Acts" (VMAs), which are designed to uphold a hierarchical gender order by promoting misogyny and questioning women's capabilities and appearances [23]. These acts not only marginalize women's achievements but also reinforce the notion that strength sports are male-dominated domains.

This study identifies a similar pattern in the stigmatization of women in golf. Although only a small number of women may feign interest in the sport, stigmatizers often generalize these isolated behaviors and apply them to the entire group. This generalization leads to a skewed perception of the social environment and atmosphere surrounding women in golf.

The stigmatization process is deeply rooted in the preexisting biases of the social environment, which often overlooks the genuine motivations and behaviors of the majority of women engaged in golf. Stigmatizers exploit the rapid dissemination and extensive coverage provided by the internet to amplify individual negative cases, thereby creating a broader, negative stereotype of the group as a whole. This process of stigmatization, which begins with the individual, escalates to group-level stigmatization and eventually solidifies into public stigmatization, reinforcing societal biases and perpetuating negative stereotypes on a larger scale.

For instance, “Could the posture be any more fake?”, from our data.

From a sociological perspective, this phenomenon illustrates how societal biases towards both the sport of golf and Chinese women can transform an individual’s failure to meet social expectations into group stigmatization. As these biases are amplified, the stigmatization extends from the group to the public domain, reinforcing and entrenching stigmatization within the broader society. This progression from individual to group to public stigmatization underscores the powerful role of social media in shaping and perpetuating societal biases.

6. Discussion

This study examines the mechanisms behind gender-based sports stigmatization, particularly in the context of Chinese women in golf. From a psychological perspective, the study highlights how traditional cultural norms and emotional triggers lead to intuitive biases (System 1), which are then reinforced by cognitive biases (System 2), ultimately resulting in stigmatizing behaviors. From a media studies perspective, the rapid spread and amplification of stigmatizing content on social media, driven by algorithms that prioritize divisive content, exacerbate these biases and contribute to the widespread stigmatization of women in sports. Sociologically, the study reveals how societal biases towards both golf and Chinese women lead to the escalation of individual stigmatization into group and public stigmatization. This progression illustrates how social media can reinforce and perpetuate existing societal biases, solidifying them into entrenched public stigmas.

6.1. Practical implications

Based on our findings, 5 strategies can be implemented to promote golf in China and counteract stigmatization:

(1).Social Events and Community Engagement: Organize large-scale golf events with widespread social media sharing, and establish youth-oriented golf clubs that create a fun, fashionable environment for young people to participate and invite friends, normalizing the sport among the younger generation.

(2).Content Creation and Storytelling: Produce vlogs, documentaries, and reality shows that document participants' experiences, highlight diverse perspectives within the golf community, and focus on the true stories of female golfers. This content can challenge stigmas and showcase the sport's broader appeal.

(3).Influencer and Celebrity Promotion: Partner with influencers and celebrities, such as Justin Bieber, to make golf more appealing to Gen Z and create positive associations with the sport among young audiences.

(4).Interviews and Personal Stories: Conduct interviews across different age groups to highlight personal stories and the positive impact of golf on individuals' lives. These stories can inspire others and reshape public perceptions of the sport.

(5).Innovative Golf Experiences: Introduce modern, engaging experiences like night golf events with DJ music, similar to LIV Golf, to combine elements that resonate with young audiences and create a vibrant, contemporary golf culture.

This reorganization consolidates the strategies into broader categories that focus on engagement, content creation, influencer promotion, storytelling, and innovation.

To reshape public opinion, it’s crucial to first educate the public about the true nature of golf and the reality of female golfers. This can be achieved through promoting the Netflix documentary <Full Swing> and the Japanese anime <Rising Impact>, giving audiences insight into the spirit of golf and reducing stigmatization.

6.2. Limitations and future directions

According to Gu Xueqiang, emoticons effectively reflect and convey the psychological states of individuals and groups, aiding in understanding, analyzing, and grasping social media behavior. However, web scraping technology struggles to capture public usage of emoticons, resulting in significant data gaps. These limitations pose challenges to the comprehensiveness and accuracy of research on stigma and its impact mechanisms. Future research should consider employing advanced technological tools and methods, such as artificial intelligence and big data analysis, to enhance the scope and accuracy of research.

7. Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the stigmatization of women in sports, particularly golf, within the Chinese social media context. By integrating grounded theory with data mining, we have unveiled the complex interplay between psychological, media, and sociological factors that drive stigmatization. The results highlight the role of social media's anonymity and algorithms in amplifying individual biases and societal stereotypes, which in turn perpetuates the stigmatization of women in golf. In conclusion, this study demonstrates the power of interdisciplinary research in solving complex social problems. Not only does it enrich our theoretical understanding of stigma, but it also serves as a call to action to promote gender equality and embrace the transformative potential of sport for all.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Matthew Grimes and Dr Xiangyuan Peng for their valuable help in finishing this painting and addressing issues about the overuse of AI. AI enabled us to recognise the middle aspects of our studies and efficiently complete the work. Our findings aim to do away with stigmatizing behaviors and permit more woman excellence in every field, keeping with Professor Feifei Li's latest booklet.

References

[1]. Kemp, S. (2023, February 9). Digital 2023: China [Report]. DataReportal. https: //datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-china

[2]. Xinhua News. (2023, August 28). China's internet users total 1.079 bln with vibrant digital infrastructure, internet app growth. State Council of the People's Republic of China.

[3]. Toffoletti, K., Ahmad, N., & Thorpe, H. (2022). "Critical Encounters with Social Media in Women's Sport and Physical Culture, " in Sport, Social Media, and Digital Technology (Vol. 15), Emerald Publishing Limited.

[4]. AlAfnan, M. A. (2024). Social Media Personalities in Asia: Demographics, Platform Preferences, and Behavior Based Analysis. Studies in Media and Communication, n. pag.

[5]. Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[6]. Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363-385. https: //doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

[7]. Jones et al.(1984). Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. W.H. Freeman and Company.

[8]. Ahmedani, B. K. (2011). Mental Health Stigma: Society, Individuals, and the Profession. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 8(2), 41-416. PMID: 22211117; PMCID: PMC3248273.

[9]. Major, B., Dovidio, J. F., Link, B. G., & Calabrese, S. K. (2020). Theoretical Models to Understand Stigma of Mental Illness. In The Cambridge Handbook of Stigma and Mental Health. Cambridge University Press. Available from [https: //www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/cambridge-handbook-of-stigma-and-mental-health/theoretical-models-to-understand-stigma-of-mental-illness/8437D63FA64D4C148789EB4A7DBED600](https: //www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/cambridge-handbook-of-stigma-and-mental-health/theoretical-models-to-understand-stigma-of-mental-illness/8437D63FA64D4C148789EB4A7DBED600)

[10]. Glossenger, D., & Cowell, A. (2021). Equity and Ability Grouping: A Study of Whole-School Practices and Reflections on Vocal Music Education.

[11]. Manzo, G. (2023). Stigmatization in Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 84(2), 8969461. [https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8969461/](https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8969461/)

[12]. Gray, D. M., & Smoczynski, A. (2024). Stigma: Advances in Theory and Research. Advances in Social Work, 24(1), 235349425. Available from [https: //www.researchgate.net/publication/235349425_Stigma_Advances_in_Theory_and_Research](https: //www.researchgate.net/publication/235349425_Stigma_Advances_in_Theory_and_Research)

[13]. National Research Council (US) Committee on the Science of Adolescence. (2011). The Science of Adolescent Risk-Taking: Workshop Report. National Academies Press (US). Available from [https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK384923/](https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK384923/)

[14]. Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2013). Labeling and Stigma. Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health, 525–541. [https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4276-5_25](https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3666955/)

[15]. Pescosolido, B. A., & Martin, J. K. (2019). The Stigma Complex. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 216. [https: //doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3](https: //bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3)

[16]. Quinn, D. M., & Earnshaw, V. A. (2011). Understanding Conceptualizations of Stigma in Conditions with Concealable Stigmatized Identities. Journal of Social Issues, 67(3), 493–507. [https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01712.x](https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3248273/)

[17]. Chaudoir, S. R., Earnshaw, V. A., & Andel, S. (2023). Disentangling the Psychological Impact of Stigma. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 8900470. [https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.8900470](https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8900470/)

[18]. Ge Ying. (2024). User Experience Evaluation of Online Platforms: A Case Study of Xiaohongshu APP. Statistics and Applications, 13(2).

[19]. Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

[20]. Guan Jian. (2007). The Conceptual Development of Stigma and the Construction of a Multidimensional Model.. Nankai Journal (Philosophy, Literature and Social Science Edition), (5)

[21]. Straton, N. (2022). COVID vaccine stigma: Detecting stigma across social media platforms with computational model based on deep learning. Applied Intelligence (Dordrecht), 1-26. Advance online publication. https: //doi.org/10.1007/s10489-022-04311-8

[22]. Tariuni, K., Musa, D. T., & Gaffar, Z. H. (2022). Komunitas Fujoshi di Pontianak dan Stigma Identitas Gender yang Melekat dalam Lingkungan Masyarakat. Balale' : Jurnal Antropologi, n. pag.

[23]. Rathje, S., Robertson, C., Brady, W. J., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2023). People Think That Social Media Platforms Do (but Should Not) Amplify Divisive Content. Perspectives on Psychological Science. Advance online publication. https: //doi.org/10.1177/17456916231190392

Cite this article

Liang,J.;Pan,J. (2025). Breaking the Bias: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Addressing Gender-based Sports Stigmatization on Social Media. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,215,107-120.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Kemp, S. (2023, February 9). Digital 2023: China [Report]. DataReportal. https: //datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-china

[2]. Xinhua News. (2023, August 28). China's internet users total 1.079 bln with vibrant digital infrastructure, internet app growth. State Council of the People's Republic of China.

[3]. Toffoletti, K., Ahmad, N., & Thorpe, H. (2022). "Critical Encounters with Social Media in Women's Sport and Physical Culture, " in Sport, Social Media, and Digital Technology (Vol. 15), Emerald Publishing Limited.

[4]. AlAfnan, M. A. (2024). Social Media Personalities in Asia: Demographics, Platform Preferences, and Behavior Based Analysis. Studies in Media and Communication, n. pag.

[5]. Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[6]. Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363-385. https: //doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

[7]. Jones et al.(1984). Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. W.H. Freeman and Company.

[8]. Ahmedani, B. K. (2011). Mental Health Stigma: Society, Individuals, and the Profession. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 8(2), 41-416. PMID: 22211117; PMCID: PMC3248273.

[9]. Major, B., Dovidio, J. F., Link, B. G., & Calabrese, S. K. (2020). Theoretical Models to Understand Stigma of Mental Illness. In The Cambridge Handbook of Stigma and Mental Health. Cambridge University Press. Available from [https: //www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/cambridge-handbook-of-stigma-and-mental-health/theoretical-models-to-understand-stigma-of-mental-illness/8437D63FA64D4C148789EB4A7DBED600](https: //www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/cambridge-handbook-of-stigma-and-mental-health/theoretical-models-to-understand-stigma-of-mental-illness/8437D63FA64D4C148789EB4A7DBED600)

[10]. Glossenger, D., & Cowell, A. (2021). Equity and Ability Grouping: A Study of Whole-School Practices and Reflections on Vocal Music Education.

[11]. Manzo, G. (2023). Stigmatization in Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 84(2), 8969461. [https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8969461/](https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8969461/)

[12]. Gray, D. M., & Smoczynski, A. (2024). Stigma: Advances in Theory and Research. Advances in Social Work, 24(1), 235349425. Available from [https: //www.researchgate.net/publication/235349425_Stigma_Advances_in_Theory_and_Research](https: //www.researchgate.net/publication/235349425_Stigma_Advances_in_Theory_and_Research)

[13]. National Research Council (US) Committee on the Science of Adolescence. (2011). The Science of Adolescent Risk-Taking: Workshop Report. National Academies Press (US). Available from [https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK384923/](https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK384923/)

[14]. Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2013). Labeling and Stigma. Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health, 525–541. [https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4276-5_25](https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3666955/)

[15]. Pescosolido, B. A., & Martin, J. K. (2019). The Stigma Complex. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 216. [https: //doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3](https: //bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3)

[16]. Quinn, D. M., & Earnshaw, V. A. (2011). Understanding Conceptualizations of Stigma in Conditions with Concealable Stigmatized Identities. Journal of Social Issues, 67(3), 493–507. [https: //doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01712.x](https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3248273/)

[17]. Chaudoir, S. R., Earnshaw, V. A., & Andel, S. (2023). Disentangling the Psychological Impact of Stigma. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 8900470. [https: //doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.8900470](https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8900470/)

[18]. Ge Ying. (2024). User Experience Evaluation of Online Platforms: A Case Study of Xiaohongshu APP. Statistics and Applications, 13(2).

[19]. Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

[20]. Guan Jian. (2007). The Conceptual Development of Stigma and the Construction of a Multidimensional Model.. Nankai Journal (Philosophy, Literature and Social Science Edition), (5)

[21]. Straton, N. (2022). COVID vaccine stigma: Detecting stigma across social media platforms with computational model based on deep learning. Applied Intelligence (Dordrecht), 1-26. Advance online publication. https: //doi.org/10.1007/s10489-022-04311-8

[22]. Tariuni, K., Musa, D. T., & Gaffar, Z. H. (2022). Komunitas Fujoshi di Pontianak dan Stigma Identitas Gender yang Melekat dalam Lingkungan Masyarakat. Balale' : Jurnal Antropologi, n. pag.

[23]. Rathje, S., Robertson, C., Brady, W. J., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2023). People Think That Social Media Platforms Do (but Should Not) Amplify Divisive Content. Perspectives on Psychological Science. Advance online publication. https: //doi.org/10.1177/17456916231190392