1. Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are the backbone of most economies; they represent about 90% of all businesses and more than 50% of employment worldwide [1]. Despite their crucial role, SMEs often face persistent financing problems, barriers that limit their capacity to innovate, expand, and compete for larger market shares in both domestic and international markets [2]. According to a study released by the World Bank, supply chain finance (SCF) has emerged as an effective alternative to traditional forms of commercial lending, which allows SMEs to unlock working capital through their supply chain relationships [3]. From Danh’s economic analysis, in Vietnam, SMEs account for 98% of all enterprises, yet contribute only 50% of employment and 40% of GDP, primarily due to generally small scale and low productivity [4]. Access to suitable and affordable financing remains a critical challenge for Vietnamese SMEs, as many of them face high borrowing costs, lack sufficient assets as collateral and have limited credit histories. While SCF has the potential to ease these constraints, the significance could be limited due to low and uneven adoption across Vietnam and SME employment growth could be further hindered by underdeveloped digital infrastructure, insufficient regulatory support and the high cost of implementing green supply chain practices [5][6]. While prior studies have engaged with SME’s financing challenges and the adoption of SCF in various contexts, research focusing on Vietnam remains limited. Existing discussions in Vietnam primarily address traditional credit constraints and banking reforms, but systematic analyses of how SCF operates within the country’s evolving legal, technological, and institutional landscape are still lacking. To address this gap, this study adopts data analysis, case study and comparative policy review, aiming to analyse the financing constraints, evaluate the potential of SCF in alleviating those barriers and identify the institutional, technological and market factors influencing its implementation in the Vietnamese context. The ultimate goal is to provide evidence-based recommendations for policymakers, financial institutions and SMEs to enhance SCF adoption and enhance sustainable growth in Vietnam.

2. Methodology

2.1. Theory framework

This study builds its theoretical foundation primarily on the Financial Constraint Theory, the Trade Credit Channel and Technology-Enabled Finance Models, which jointly explain the mechanisms through which SCF adoption can affect SME performance under financing constraints.

Firstly, Financial Constraint Theory posits that firms facing borrowing frictions, such as insufficient collateral, lack of formal credit history, information asymmetries or high lending costs, are unable to invest optimally, especially small and medium-sized enterprises [7]. SCF, by leveraging the creditworthiness of larger buyers, which is reflected in their credit ratings, payment reliability and established transaction records, potentially allows constrained SMEs to access liquidity without traditional collateral, thereby easing underinvestment problems. Secondly, the Trade Credit Channel supports the idea that interfirm credit within supply chains can act as a substitute for bank finance. However, without formal financial intermediation or digital validation of receivables, this channel remains informal and limited. SCF institutionalizes and scales up the trade credit channel by enhancing reliability and enforceability”, “institutionalizes and scales up [8]. In Vietnam, the persistence of a large informal economy and weak contract enforcement further amplify these financing constraints, limiting the effectiveness of traditional trade credit arrangements. Thirdly, Technology-Enabled Financed Model highlights that the effectiveness of SCF solutions is amplified when digital infrastructure reduces verification costs, strengthens contract enforceability and mitigates information asymmetries [9]. In contexts like Vietnam, digital readiness functions as a moderating variable: its underdevelopment directly impedes SCF’s effectiveness. Together, these theoretical lenses justify why SCF can be a powerful policy and market tool for SME development and clarify why implementation outcomes vary across institutional contexts.

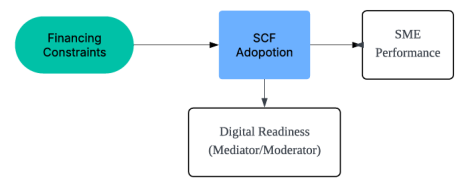

2.2. Research framework

This research proposes a conceptual framework to illustrate the hypothesized relationships between financing constraints, SCF adoption and SME performance, with digital readiness acting as a mediating or moderator variable. SCF is an alternative financing channel that can alleviate liquidity constraints for SMEs, particularly those lacking sufficient collateral or formal credit history, by enabling access to more working capital through supply chain [10]. However, the effectiveness of SCF is highly dependent on the digital readiness of SMEs. Firms with stronger technological capability, especially those adopting database management, blockchain, and AI technologies, show significantly better SCF outcomes through reduced information asymmetry, enhanced transparency and improved risk management [11].

2.3. Data framework

The data in Table 1 are complied from multiple authoritative sources. Macroeconomic indicators such as GDP and government budget are drawn from Worldometer and Vietnam’s official budget statistics, while lending interest is taken from the World Bank database [12][13][14]. SME-related figures, including employment share and GDP contribution, are based on Roles of Access to Finance in SME Development in Viet Nam (PSOWP 2) [15]. Trade finance and supply chain finance indicators are sourced from the WTO-IFC (2023) report on boosting trade finance in the Mekong region [16].

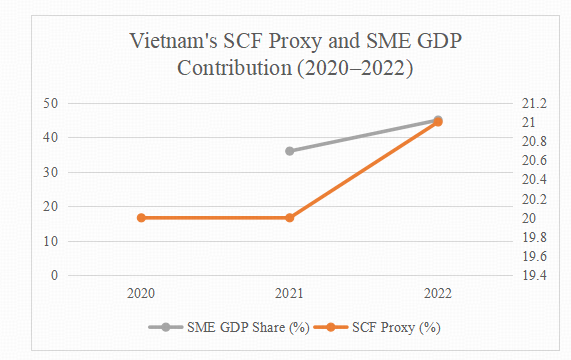

As shown in Table 1, to evaluate the development of SCF and its relationship with SMEs in Vietnam, this study examines key macroeconomic and sector-specific indicators for the period 2020–2022. Due to the absence of official SCF volume data, this study uses trade finance as a percentage of trade as a proxy, since SCF instruments are often embedded within broader trade finance activities and this indicator reflects the extent to which financial institutions support transactions across supply chains. Theoretically, both trade finance and SCF operate to improve liquidity for supply chain firms, especially SMEs reliant on trade flows rather than collateral-based credit [17]. However, trade finance penetration in Vietnam remained relatively low, rising slightly from less than 20% to 21%. In fact, according to AMRO using FCI data, Vietnam’s factoring volume in 2022 was just $ 1.1 billion, representing a mere 0.15% of its total trade volume [18]. During the same period, SMEs contributed significantly to employment, accounting for over 35% of the national labor force, though it was presented in a slowly decreasing trend, partly due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Notably, SME’s contribution to GDP increased from 36% in 2021 to 45% in 2022, increasing stronger output performance despite a decline in workforce. This expansion can be partly attributed to government support measures during the post-pandemic recovery, sectoral shifts toward manufacturing and services with higher value-added and improvements in SME integration into global supply chains. Meanwhile, Vietnam’s GDP expanded from $346.6 billion to $410.3 billion, supported by active fiscal policies, as evidenced by rising fiscal expenditures and consistent budget deficits, while lending rates remain around 8%, reflecting the credit constraints faced by SMEs and highlighting the critical role of SCF as an alternative financing channel to support liquidity and business continuity.

|

Year |

SCF as % of trade |

SCF Proxy (Trade Finance as % of Trade) |

SME Employment Share (%) |

GDP $ in billion |

GDP Generated by SME |

Fiscal Expenditure (% of GDP) |

Government Budget (% of GDP) |

Lending Interest Rate (%) |

|

2020 |

NA |

|

36.3 |

346.62 |

NA |

2.3 |

-3.2 |

7.6 |

|

2021 |

NA |

20 |

36.1 |

366.48 |

36% |

3.7 |

-3.41 |

7.8 |

|

2022 |

0.15 |

21 |

35 |

410.32 |

45% |

9.7 |

-4.1 |

8 |

3. Empirical Analysis

3.1. Current constraint

Although SCF is designed to shift credit risk away from small suppliers towards stronger buyers, its implementation continues to face significant challenges. In theory, SCF programs allow suppliers to access working capital based on the creditworthiness of their buyers. However, banks and financial institutions still require verified transaction data, such as electronic invoices, purchase orders, delivery receipts and legally enforceable receivables assignments, to evaluate creditworthiness and ensure repayment [19].

In Vietnam, the adoption of digital and legal infrastructures, such as electronic invoicing systems, receivables registration frameworks and mechanisms for contract enforcement, remains limited. From 2020 to 2022, the proportion of Vietnam’s total trade supported by trade finance instruments used here as a proxy for SCF remained low, fluctuating between 20 and 21% despite strong trade performance during the same period. Notably, Vietnam recorded a consistent trade surplus in each of these three years, with its trade balance rising from USD 6.8 billion in 2020 to USD 7.3 billion in 2022 [20]. Concurrently, SME employment share declined from 36.3% in 2020 to 35% in 2022, although their GDP contribution ranged between 36% and 45%.

One persistent constraint is Vietnamese commercial banks’ reliance on immovable collateral such as land-use rights and buildings, and audited financial statements to underwrite SME credit. Many SMEs, however, operate with thin balance sheets, informal bookkeeping and limited audited records, making it difficult to demonstrate cash flow capacity or pledge sufficient collateral [21].

The limited scale of Vietnam’s Credit Guarantee Fund underscores its insufficient coverage. With a total charter capital of only about VND 1.5 trillion (approximately USD 60 million) and a maximum guarantee capacity of around VND 4.5 trillion (USD 180 million), the scheme falls far short of SMEs’ aggregate financing needs, estimated in the billions of USD annually [22]. Given that negligible fraction of the sector, both in terms of volume and beneficiary enterprises. This disparity highlights why the current guarantee mechanism is inadequate to substantially ease credit constraints for SMEs. In practice, banks still prefer fixed assets over receivables or inventory as collateral. The national credit bureau also lacks access to rich transactional data from tax records, e-commerce platforms and enterprise systems. This makes it difficult for SMEs without real estate to access affordable credit and SCF programs, even when their trade flows are stable and low-risk.

To unlock the full potential of SCF for SMEs, Vietnam must prioritize investments in digital infrastructure, such as nationwide e-invoicing systems. Furthermore, improving the legal environment for receivables assignment and expanding credit information coverage will be critical to scaling up inclusive, sustainable SCF models.

On the informational side, Vietnam’s credit system remains underdeveloped, with limited coverage of smaller firms and insufficient integration of alternative data sources such as tax filings, and e-commerce activity [23]. Consequently, credit histories for many SMEs are incomplete or unavailable. Even when SMEs maintain regular trade flows with large buyers, the lack of digital footprint and enforceable receivables leads banks to treat SCF exposures as quasi-unsecured, thereby limiting the size and scalability of such programs.

3.2. Horizontal comparison

To put Vietnam’s SME performance in perspective, a horizontal comparison with regional peers is revealing. In Vietnam, formal SMEs (1-249 employees) employ about 47% of the labour force and generate 36% of GDP, significantly below the OECD average. By contrast, based on 2018-2019 )ECD data, in South Korea, SMEs account for approximately 99% of enterprises and 80-88% of employment. In Mexico, SMEs generate roughly 52% of GDP and account for 72% of formal employment [21]. These comparisons underscore that Vietnamese SMEs remain under-leveraged relative to peers, which signals untapped policy and financial integration opportunities.

In Mexico, trade and supply chain finance flows are notably larger than those in Vietnam. In 2023, Mexican banks intermediated approximately USD 91.3 billion in trade and supply chain finance, accounting for 8% of the country’s merchandise trade volume and 11% of total bank assets [24]. Despite this relatively high penetration, most SCF still benefits large firms, while smaller exporters face liquidity gaps, reflecting structural credit access issues similar to Vietnam’s.

In South Korea, while detailed SCF adoption data in open sources are scarce, the broader trade finance market is mature and growing rapidly, with a forecast compound annual growth rate of 6-7% through the late 2020s [25]. Notably, major global and local banks, including Woori, KB and Citibank, play active roles in the expanding trade finance ecosystem, using advanced technologies and export-oriented financing models to support SMEs and larger exporters.

These contrasting case studies indicate that while Mexico has achieved higher SCF penetration by bank asset share than Vietnam, South Korea’s SCF infrastructure benefits from a sophisticated, technology-enabled banking sector, which could offer valuable lessons for Vietnam’s financial modernization efforts and policy formulation.

4. Future Pathways

Providing effective SCF to SMEs hinges on a healthy policy environment. In the short term, Vietnam should expand the collateral framework to include receivables and inventory, and simplify the legal enforcement of these movable assets, strengthening lenders’ confidence in SCF practices. Additionally, partial credit guarantee schemes must be scaled up to reduce banks’ risk aversion when lending to SMEs [23]. Over the long term, institutional reforms are needed to enhance judicial efficiency around contract enforcement and integrate alternative data sources, such as tax filing and e-commerce transactions, into national credit assessment systems. These reforms can reduce information asymmetry and unlock SMEs’ access to formal finance [26].

Digital technologies are pivotal for facilitating SME access to SCF, a priority also reflected in Vietnam’s National Digital Transformation Program to 2025 (with orientation toward 2030), which emphasizes universal adoption of e-invoicing, digital payment systems and electronic business registries to strengthen transparency and financial inclusion. Rapid adoption of electronic invoicing systems lowers verification costs and mitigates information gaps, enabling “faster, more reliable financing decisions [27]. Looking forward, establishing a national SCF platform that leverages e-KYC, blockchain, and AI-based risk evaluation can modernize the landscape, ensuring transaction-level reliability and scalability for both banks and fintech providers. Industrywide digital integration gives banks confidence to underwrite SCF on the strength of real transaction data, rather than collateral alone [28].

Global sustainability trends are reshaping supply chain expectations. In the short term, incentives that encourage SMEs to adopt greener practices, such as energy-efficient upgrades or eco-certifications, can prepare them for sustainability-linked SCF models have been promoted in order markets and carbon reduction goals. These sustainability-linked financing models that have been promoted in other markets to drive SME alignment with buyer-driven ESG standards [29]. Such green financing channels not only improve SME’s competitive positioning in global value chains, particularly in the face of regulatory mechanisms like the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, but also contribute to domestic environmental goals.

5. Conclusion

This study has examined the financing challenges of Vietnamese SMEs and the role of SCF as a potential solution. SMEs remain vital, contributing 36-45% of GDP and 35-36% of employment from 2020 to 2022, but they still face persistent financing barriers, primarily stemming from banks’ reliance on collateral-based lending, SMEs’ incomplete credit histories, and underdeveloped digital infrastructure. While SCF is designed to ease liquidity by shifting credit risk to stronger buyers, adoption in Vietnam remains limited. Trade finance covered only 20-21% of trade, and SCF as a percentage of trade accounted for just 0.15% in 2022. Compared to Mexico and Korea, where SMEs contribute a larger share of GDP and employment, Vietnam’s SMEs remain under-leveraged, reflecting missed opportunities. To unlock SCF’s potential, short-term reforms must prioritize wider use of receivables as collateral, stronger credit guarantees, and nationwide adoption of e-invoices. Long-term success requires judicial enforcement, deeper credit-information systems, and sustainability-linked SCF instruments to align with global green supply chain pressures. In short, Vietnam’s SCF is still nascent but carries significant promise. With targeted reforms, it can expand SME access to finance, foster inclusive growth, and strengthen Vietnam’s competitiveness in the global supply chain.

References

[1]. Nguyen, D. N., et al. (2022). The effect of supply chain finance on supply chain risk, supply chain risk resilience, and performance of Vietnam SMEs in global supply chain. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 10(1), 225–238.

[2]. G. Falavigna, R. Ippoliti, & Ramello., G. B. (2025). Financial constraints, institutional quality and import trade flows: An empirical investigation on Italian manufacturing SMEs. International Business Review, 34.

[3]. Bank, W. (2023). Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Finance. World Bank. Retrieved Auguest 8th from https: //www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance

[4]. Le, D. V., Le, H. T. T., Pham, T. T., & Vo, L. V. (2023). Innovation and SMEs performance: evidence from Vietnam. Applied Economic Analysis, 31(92), 90-108. https: //doi.org/10.1108/aea-04-2022-0121

[5]. Khoa Dang Duong, et al. (2024). How do financial constraints and market competition affect innovations: Evidence from Vietnam Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 10(3).

[6]. Le, T. T., Vo, X. V., & Venkatesh, V. G. (2022). Role of green innovation and supply chain management in driving sustainable corporate performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 374, 133875.

[7]. Fazzari, S. M., Hubbard, G. R., & Petersen, B. C. (1988). Financing constraints and corporate investment. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 141–206. https: //doi.org/10.2307/2534426

[8]. Petersen, M. A., & Rajan, R. G. (1997). Trade credit: Theories and evidence. Review of Financial Studies, 10(3), 661–691. https: //doi.org/10.1093/rfs/10.3.661

[9]. Lou, Z., Xie, Q., Shen, J. H., & Lee, C.-C. (2024). Does Supply Chain Finance (SCF) alleviate funding constraints of SMEs? Evidence from China. Research in International Business and Finance, 67(PA).

[10]. Zhaohui Lou, Qizhuo Xie, Jim Huangnan Shen, & Chien-Chiang Lee. (2024). oes Supply Chain Finance (SCF) alleviate funding constraints of SMEs? Evidence from China. Research in International Business and Finance. https: //doi.org/https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2023.102157

[11]. Wang Jia, Nur Aima Shafie, & Kasim., E. S. (2025). The Impact of Digital Technology on Supply Chain Finance Performance of Chinese SMEs - A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 12(01). https: //doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v15-i1/

[12]. Worldometer. (2025, September 6). Vietnam GDP. Retrieved from https: //www.worldometers.info/gdp/vietnam-gdp/

[13]. Vietnam General Statistics Office. (n.d.). State budget expenditure as a percentage of GDP [Data set]. Retrieved from National Statistics Office of Vietnam website: https: //www.nso.gov.vn/en/px-web?pxid=E0316& theme=National+Accounts+and+State+budget

[14]. World Bank. (n.d.). Lending interest rate (%) (FR.INR.LEND) [Data set]. Retrieved September 6, 2025, from https: //data.worldbank.org/indicator/FR.INR.LEND

[15]. Nguyen, N. A. (2024). Roles of Access to Finance in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Development in Viet Nam (PSOWP 2) [Policy research working paper]. Asian Development Bank. Retrieved from https: //www.adb.org/publications/access-finance-sme-development-viet-nam

[16]. World Trade Organization & International Finance Corporation. (2023, December 13). Trade Finance in the Mekong Region [News release]. Retrieved from https: //www.wto.org/english/news_e/news23_e/publ_13dec23_e.htm

[17]. Organization, W. T. (2023). Trade Finance in the Makong Region. https: //www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/tf_mekong_e.pdf

[18]. ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office. (2025, March). Vietnam: 2024 Annual Consultation Report (ACR/2503). Bangkok, Thailand: AMRO. Retrieved from https: //amro-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/2024-Vietnam-ACR_publication_21Feb2025.pdf

[19]. International Finance Corporation. (2024, January 11). Knowledge Guide on Factoring Regulation and Supervision. World Bank Group. Retrieved from https: //www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2024/knowledge-guide-on-factoring-regulation-and-supervision

[20]. Doan, B. T. (2025). Trends and determinants of Vietnam’s trade balance: Evidence from import–export data. Financial Economics Insights, 2(1), 1–8. https: //soapubs.com/index.php/FEI

[21]. OECD. (2021). SME and entrepreneurship policy in Viet Nam (OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship). OECD Publishing. https: //doi.org/10.1787/30c79519-en

[22]. ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office. (2023). Vietnam: 2023 Annual Consultation Report – Supplementary Information on Credit Guarantee. Singapore: AMRO. Retrieved from https: //amro-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Vietnam_2023-Annual-Consultation-Report_-SI-on-Credit-Guarantee-1.pdf

[23]. Asian Development Bank. (2024, December). Access to finance for SME development in Viet Nam (Working Paper Series No. 2). Manila: ADB. Retrieved from https: //www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/1016211/psowp-2-access-finance-sme-development-viet-nam.pdf

[24]. World Trade Organization & International Finance Corporation. (2025, April 29). Trade finance in Central America and Mexico: A study of Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico. WTO. Retrieved from https: //www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/tradefinance_centam_chap2_e.pdf

[25]. Mordor Intelligence. (2025, January 10). South Korea Trade Finance Market Size & Share Analysis (2025–2030). Retrieved from https: //www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/south-korea-trade-finance-market

[26]. Nguyen Viet Hung, Thanh, T. T., Hoa, H. Q., Dat, T. T., & Nam, P. X. (2020). Constraints of Small and Medium Enterprises Access to Bank Loans: Evidence from Vietnam Manufacturing Firms. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 24(1). Retrieved from https: //www.abacademies.org/articles/constraints-of-small-and-medium-enterprises-access-to-bank-loans-evidence-from-vietnam-manufacturing-firms-8951.html

[27]. Tiwari, A. K., Marak, Z. R., Paul, J., & Deshpande, A. P. (2023). Determinants of electronic invoicing technology adoption: Toward managing business information system transformation. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 8(3), Article 100366. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2023.100366

[28]. World Bank Group. (2021). Vietnam Country Private Sector Diagnostic. Washington, DC: World Bank and IFC.This report highlights that Vietnamese banks supported about 21% of exports and imports with trade finance, and that SCF accounted for only 0.1%–0.4% of surveyed banks' assets, underscoring the limited penetration of SCF in Vietnam’s financial ecosystem.

[29]. Alvarez & Marsal. (2024, October 3). Alvarez & Marsal: Unlocking Sustainable Supply Chain Finance. Supply Chain Digital. Retrieved from https: //supplychaindigital.com/sustainability/alvarez-and-marsal-sustainable-scf-report

Cite this article

Deng,S. (2025). Supply Chain Finance for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises in Vietnam: Current State and Future Pathways. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,221,68-75.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICFTBA 2025 Symposium: Global Trends in Green Financial Innovation and Technology

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Nguyen, D. N., et al. (2022). The effect of supply chain finance on supply chain risk, supply chain risk resilience, and performance of Vietnam SMEs in global supply chain. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 10(1), 225–238.

[2]. G. Falavigna, R. Ippoliti, & Ramello., G. B. (2025). Financial constraints, institutional quality and import trade flows: An empirical investigation on Italian manufacturing SMEs. International Business Review, 34.

[3]. Bank, W. (2023). Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Finance. World Bank. Retrieved Auguest 8th from https: //www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance

[4]. Le, D. V., Le, H. T. T., Pham, T. T., & Vo, L. V. (2023). Innovation and SMEs performance: evidence from Vietnam. Applied Economic Analysis, 31(92), 90-108. https: //doi.org/10.1108/aea-04-2022-0121

[5]. Khoa Dang Duong, et al. (2024). How do financial constraints and market competition affect innovations: Evidence from Vietnam Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 10(3).

[6]. Le, T. T., Vo, X. V., & Venkatesh, V. G. (2022). Role of green innovation and supply chain management in driving sustainable corporate performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 374, 133875.

[7]. Fazzari, S. M., Hubbard, G. R., & Petersen, B. C. (1988). Financing constraints and corporate investment. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 141–206. https: //doi.org/10.2307/2534426

[8]. Petersen, M. A., & Rajan, R. G. (1997). Trade credit: Theories and evidence. Review of Financial Studies, 10(3), 661–691. https: //doi.org/10.1093/rfs/10.3.661

[9]. Lou, Z., Xie, Q., Shen, J. H., & Lee, C.-C. (2024). Does Supply Chain Finance (SCF) alleviate funding constraints of SMEs? Evidence from China. Research in International Business and Finance, 67(PA).

[10]. Zhaohui Lou, Qizhuo Xie, Jim Huangnan Shen, & Chien-Chiang Lee. (2024). oes Supply Chain Finance (SCF) alleviate funding constraints of SMEs? Evidence from China. Research in International Business and Finance. https: //doi.org/https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2023.102157

[11]. Wang Jia, Nur Aima Shafie, & Kasim., E. S. (2025). The Impact of Digital Technology on Supply Chain Finance Performance of Chinese SMEs - A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 12(01). https: //doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v15-i1/

[12]. Worldometer. (2025, September 6). Vietnam GDP. Retrieved from https: //www.worldometers.info/gdp/vietnam-gdp/

[13]. Vietnam General Statistics Office. (n.d.). State budget expenditure as a percentage of GDP [Data set]. Retrieved from National Statistics Office of Vietnam website: https: //www.nso.gov.vn/en/px-web?pxid=E0316& theme=National+Accounts+and+State+budget

[14]. World Bank. (n.d.). Lending interest rate (%) (FR.INR.LEND) [Data set]. Retrieved September 6, 2025, from https: //data.worldbank.org/indicator/FR.INR.LEND

[15]. Nguyen, N. A. (2024). Roles of Access to Finance in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Development in Viet Nam (PSOWP 2) [Policy research working paper]. Asian Development Bank. Retrieved from https: //www.adb.org/publications/access-finance-sme-development-viet-nam

[16]. World Trade Organization & International Finance Corporation. (2023, December 13). Trade Finance in the Mekong Region [News release]. Retrieved from https: //www.wto.org/english/news_e/news23_e/publ_13dec23_e.htm

[17]. Organization, W. T. (2023). Trade Finance in the Makong Region. https: //www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/tf_mekong_e.pdf

[18]. ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office. (2025, March). Vietnam: 2024 Annual Consultation Report (ACR/2503). Bangkok, Thailand: AMRO. Retrieved from https: //amro-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/2024-Vietnam-ACR_publication_21Feb2025.pdf

[19]. International Finance Corporation. (2024, January 11). Knowledge Guide on Factoring Regulation and Supervision. World Bank Group. Retrieved from https: //www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2024/knowledge-guide-on-factoring-regulation-and-supervision

[20]. Doan, B. T. (2025). Trends and determinants of Vietnam’s trade balance: Evidence from import–export data. Financial Economics Insights, 2(1), 1–8. https: //soapubs.com/index.php/FEI

[21]. OECD. (2021). SME and entrepreneurship policy in Viet Nam (OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship). OECD Publishing. https: //doi.org/10.1787/30c79519-en

[22]. ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office. (2023). Vietnam: 2023 Annual Consultation Report – Supplementary Information on Credit Guarantee. Singapore: AMRO. Retrieved from https: //amro-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Vietnam_2023-Annual-Consultation-Report_-SI-on-Credit-Guarantee-1.pdf

[23]. Asian Development Bank. (2024, December). Access to finance for SME development in Viet Nam (Working Paper Series No. 2). Manila: ADB. Retrieved from https: //www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/1016211/psowp-2-access-finance-sme-development-viet-nam.pdf

[24]. World Trade Organization & International Finance Corporation. (2025, April 29). Trade finance in Central America and Mexico: A study of Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico. WTO. Retrieved from https: //www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/tradefinance_centam_chap2_e.pdf

[25]. Mordor Intelligence. (2025, January 10). South Korea Trade Finance Market Size & Share Analysis (2025–2030). Retrieved from https: //www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/south-korea-trade-finance-market

[26]. Nguyen Viet Hung, Thanh, T. T., Hoa, H. Q., Dat, T. T., & Nam, P. X. (2020). Constraints of Small and Medium Enterprises Access to Bank Loans: Evidence from Vietnam Manufacturing Firms. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 24(1). Retrieved from https: //www.abacademies.org/articles/constraints-of-small-and-medium-enterprises-access-to-bank-loans-evidence-from-vietnam-manufacturing-firms-8951.html

[27]. Tiwari, A. K., Marak, Z. R., Paul, J., & Deshpande, A. P. (2023). Determinants of electronic invoicing technology adoption: Toward managing business information system transformation. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 8(3), Article 100366. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2023.100366

[28]. World Bank Group. (2021). Vietnam Country Private Sector Diagnostic. Washington, DC: World Bank and IFC.This report highlights that Vietnamese banks supported about 21% of exports and imports with trade finance, and that SCF accounted for only 0.1%–0.4% of surveyed banks' assets, underscoring the limited penetration of SCF in Vietnam’s financial ecosystem.

[29]. Alvarez & Marsal. (2024, October 3). Alvarez & Marsal: Unlocking Sustainable Supply Chain Finance. Supply Chain Digital. Retrieved from https: //supplychaindigital.com/sustainability/alvarez-and-marsal-sustainable-scf-report