1. Introduction

With the rapid development of social media in China, social media platforms and relevant industries (e.g., multi-channel networks [MCN]) achieved unprecedented development simultaneously. As a result, some contributors gain a large following, establish a fan base, and serve as a resource for their followers due to the internet's scale and speed of dispersion, becoming social media influencers (SMIs). Instagram, YouTube, and Facebook have created a large audience for digital influencers to promote their content, primarily for commercial goals, such as brand endorsement [1,2]. Parallel to the popularity of SMIs, Influencer marketing has become a type of social media marketing that uses endorsements made by people, organizations, and groups seen as influential or experts in a particular area [3].

Previous studies on influencer marketing provide an overview of who SMIs are and how they influence consumers. However, the previous study seems to have partially overlooked the relationship between SMIs and their followers. There remains substantially unknown about the interaction between SMIs and followers [4,5]. Current studies mainly focus on celebrity capital structuring framework and optimization of such capital [6,7]. This study aims to explain consumers' preferences when they follow an SMI and their parasocial relationship and endorsement effectiveness with followers. This research merely focuses on the Douyin platform in China. Douyin (Chinese: 抖音), known as the Chinese version of TikTok, is a short-form video hosting service owned by the Chinese company ByteDance [8]. Douyin is the most used social network in China, with a user share of 76%, and 40% of Douyin users state that they have bought products because celebrities or SMIs advertised them [9]. Therefore, this study takes Douyin as an example and would provide some optimization and insights for influencer marketing strategy in China.

2. Theoretical Basis and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Influencer Marketing in China

Social media development led marketing to a revolutionary stage, as well as differing the relationships between SMIs, consumers, and brands [10]. The comparison of traditional marketing tools and digital marketing illustrated by marketing managers showed that influencer marketing might generate higher returns than traditional marketing strategies [11]. With fierce competition in China, it is challenging to stand out from the rest of the market. Chinese consumers were tired of traditional advertising and have started looking for recommendations or reviews from people who are similar to them and share the same evaluative criteria [12]. This study explores the relationship between Chinese SMIs and followers and Chinese followers' preferences.

2.2. Gender Difference

Previous studies revealed that the gender of the endorser affects the consumer’s attitude and behaviour toward celebrity endorsement [13]. Moreover, Females are relatively more sensitive and other-focused. However, men are more likely to be self-focused. In contrast to men, women are more susceptible to influence and persuasion, specifically when exposed to specific informational sources like friends, magazines, and publications [14,15]. Therefore, it could be inferred that female and male users act differently on social media, and this study should warrant further research into gender differences in influencer marketing. To summarize,

• H1. Female and male users act differently in following an SMI.

• H2. Douyin users prefer to follow SMIs of the same gender as them.

Likewise, it is rational to suggest that differences between the different age groups of followers and SMIs also may show a difference in their interactions. Thus, this study also assumes that:

• H3. Douyin users prefer to follow SMIs of their age.

2.3. Parasocial Interaction

Social media platforms like YouTube and TikTok are viral because such platforms provide the opportunity for social connections with other users, including real-life friends and even SMIs. The boundaries seem flexible and vague [16]. Followers consider they build connections, although unbalanced, with SMI by like, comment, and share functions. Such a phenomenon could be explained as parasocial interaction. The concept of "parasocial interaction" refers to the one-sided, virtual relationship that people have with media personalities to seek guidance and treat them as friends desiring to meet media performers during media interactions. This process is analogous to realistic interpersonal communication [17,18]. In influencer marketing, SMIs build interpersonal relationships with their followers, affect followers' cognition and emotion, and eventually influence their behaviour [19]. Therefore, this study assumes that SMIs could affect followers' use and purchase behaviour on social media platforms. To summarize:

• H4. Douyin users who follow more SMIs spend more time browsing content generated by these following SMIs.

• H5. The number of SMIs Douyin users followed correlates with the number and the average price of influencer-motivated purchases.

Taken together, H1, H2, and H3 suggest that people prefer to follow SMIs of their gender and age. Furthermore, H4 and H5 assume that the more SMIs people follow, the more time and money they spend affected by SMIs. In conclusion, this study could elucidate users' choices when following an SMI and their parasocial interactions and endorsement effect with followers.

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire Design

The current study used a survey instrument with three sections to conduct a quantitative analysis. The first section collected respondents' demographic information, including gender, age, and job. The second section concerns respondents' social media user behaviour, including daily duration, preferred content category, and SMI following status. The last section collected the respondent's purchasing behaviour information (e.g., purchasing frequency, motivation, SMI's effect on purchasing).

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

The questionnaire, including multiple choice and short answer questions, was designed and distributed through dominant Chinese social media (e.g., Sina Weibo, Wechat) by QR code and link. A total of 341 surveys were initially gathered. Screening questions and responders' recollection questions were checked to exclude unqualified participants. After data cleaning, a total of 293 valid results were used for analysis in general. Approximately 41.4% of responders were male, and 58.3% were male, ranging from 15 to 63. Regarding employment, 41.4% were students, 43.8% worked full-time, 4.5% worked part-time, 1.5% were retired, and 8.6% were others. However, the sample number requires an extra screening for the different hypotheses.

3.3. Procedure and Data Analysis

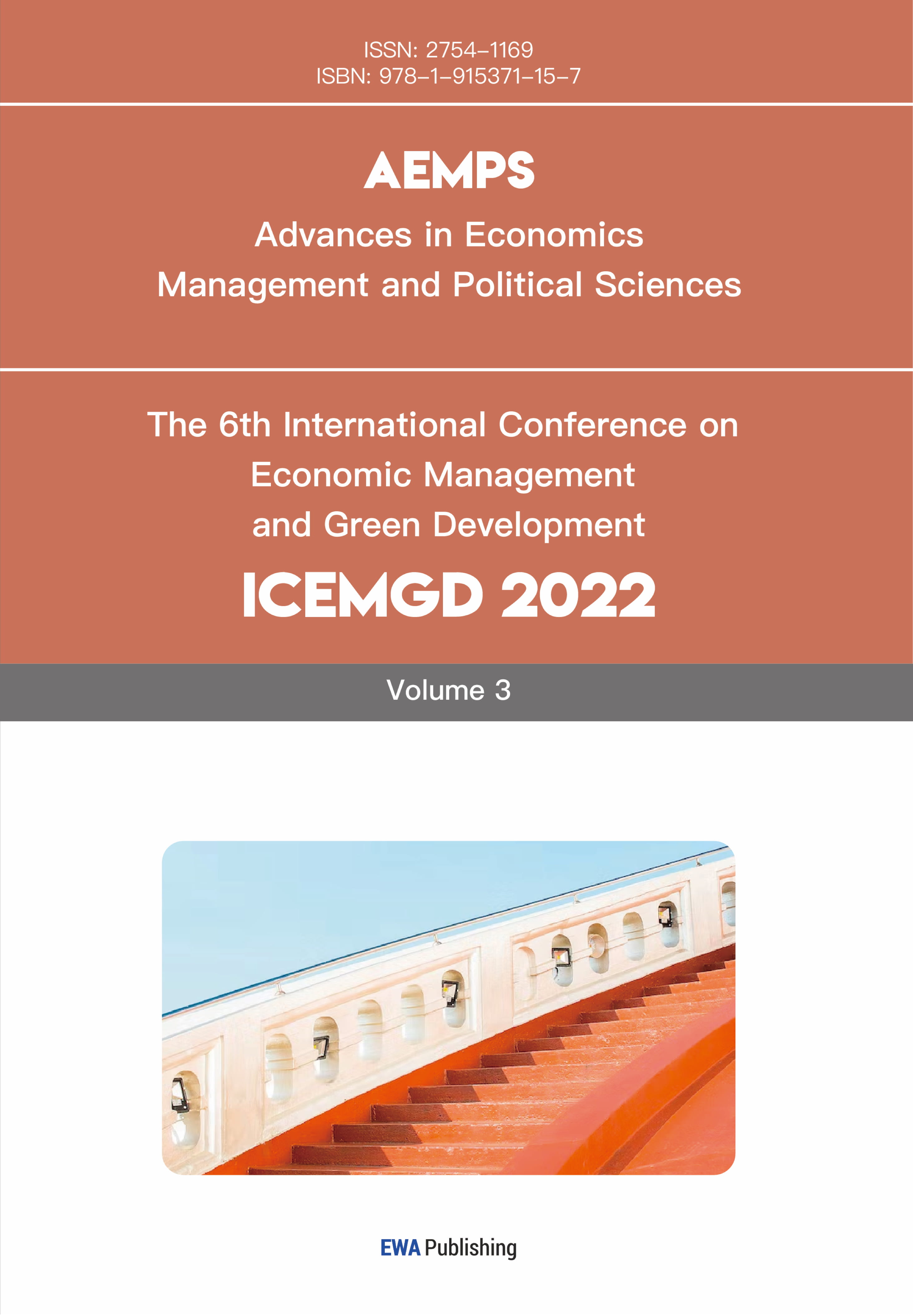

\( {H_{1}} \) followed a two-sample t-test to compare the behaviour of the number of following SMIs in female and male users. There was a significant difference in user behavior regarding the number of following SMIs between female users ( \( M =86.7, SD =125 \) ) and male users ( \( M = 37.4, SD = 61.5); t (293) = 4.0225, (p =7.334×{10^{-5}} \) ). Figure 1 shows the difference in user behaviour regarding the number of following SMIs between female and male users. The result of the T-test and visualization suggests that \( {H_{1}} \) was supported.

Figure 1: Boxplot of H1.

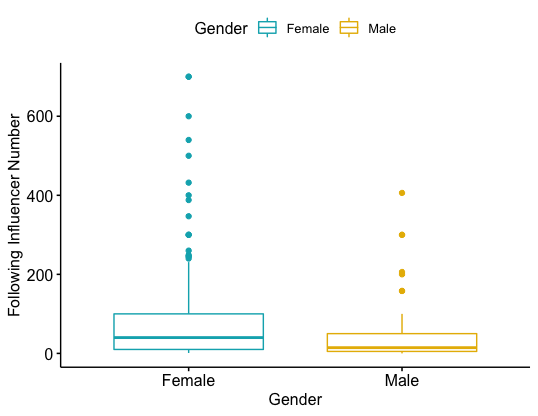

To test \( {H_{2}} \) , the 2 X 2 Contingency Chi-square test was performed to compare male and female users on the gender of the SMI they followed. Results indicated that 77.9% of female SMIs ’followers were female, whereas 67.0% of male SMIs’ followers were male. This difference was significant between the two variables, \( {χ^{2}}(1,N=243) = 47.45, p =5.642×{10^{-12}} \) .

The visualization of Pearson residuals (Figure 2) was used in a Chi-Square Test of Independence to analyze the difference between observed responses [20]. The blue positive residuals show an association between the column of female SMIs and the row of female users. Similarly, there is a strong positive association between the column male SMIs and the row male users. Conversely, harmful residuals in red implied repulsions (negative association).

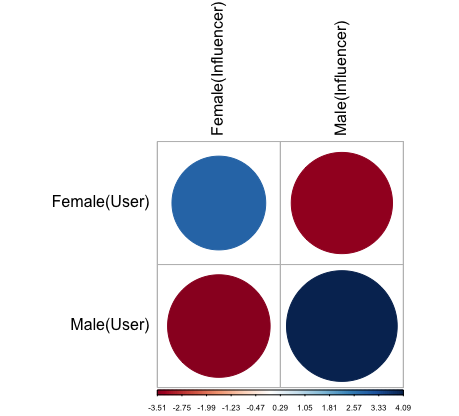

Like \( {H_{2}} \) , \( {H_{3}} \) followed a chi-square test to examine whether the user’s age group and SMI’s age group are statistically significantly associated. There was a significant relationship between the two variables, \( {χ^{2}}(16,N=277) = 209.68, p =2.2×{10^{-16}} \) .

Figure 2: Pearson residual visualization of H2.

Continuing, as Figure 3 illustrates, positive residuals are in blue. Positive values in cells specify an attraction (positive association) between the user’s age group and the age group of SMIs they followed. There is a strong positive association between the column 10-19, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, >50 and the row 10-19, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, >50 respectively. Hence, \( {H_{2}} and {H_{3}} \) were all supported.

Figure 3: Pearson residual visualization of H3.

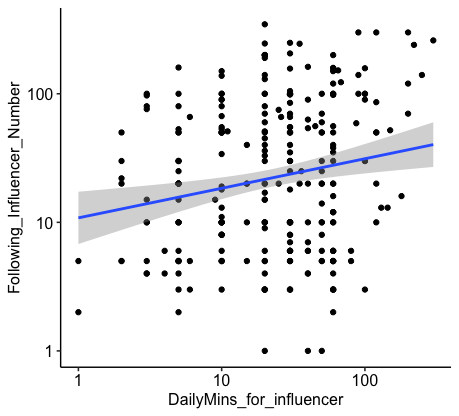

\( {H_{4}} \) implied a simple linear regression model to evaluate the correlation coefficient measuring the association level between the number of SMIs users followed and the time spent browsing content generated by these following SMIs. Besides, log transformations are performed for skewed data. After a log transformation, the original data became more symmetric to meet the normality assumption. As a result, there is a significant relationship ( \( p =0.00158 \lt 0.01 \) ) between the number of SMIs users followed and the time spent browsing content generated by these following SMIs.

Additionally, the visualization of \( {H_{4}} \) was generated in Figure 4. Therefore, \( {H_{4}} \) was supported.

Figure 4: Regression line and the scatter plot of H5.

To test \( {H_{5}} \) , a multiple linear regression model was used to examine whether the number of SMIs that users followed correlates with the number and the average price of influencer-motivated purchases. The P-value of the F-statistic is \( p =27.921×{10^{-5}} \lt 0.001 \) , which is highly significant. The regression equation is \( y=-2.8034+24.436{x_{1}}+0.27{x_{2}} \) . In 234 samples, there are significant relationships between the number of SMIs that users followed and the number and the average price of influencer-motivated purchases ( \( p=0.00209 \lt 0.01, p=0.01465 \lt 0.05 \) , respectively). Hence, \( {H_{5}} \) was supported.

3.4. Followers’ Preference and Motivation Analysis

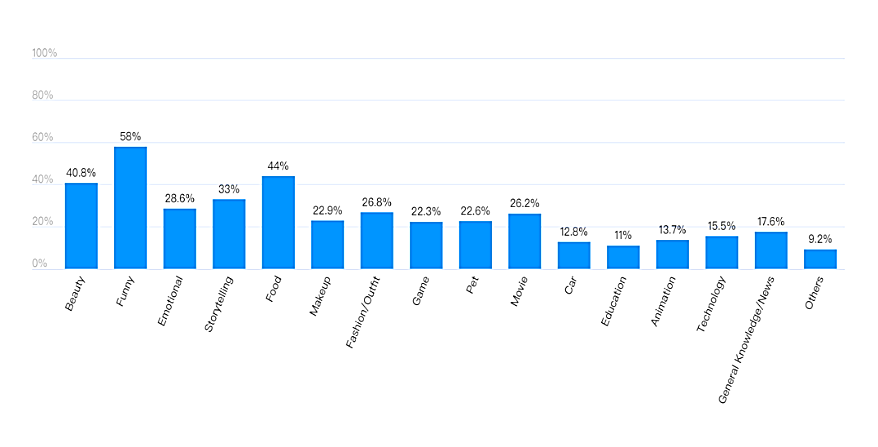

According to the result of the select short-video category (Figure 5), the top three welcomed categories are funny (58%), food (44%), and beauty (40.8%).

Figure 5: Distribution by content category.

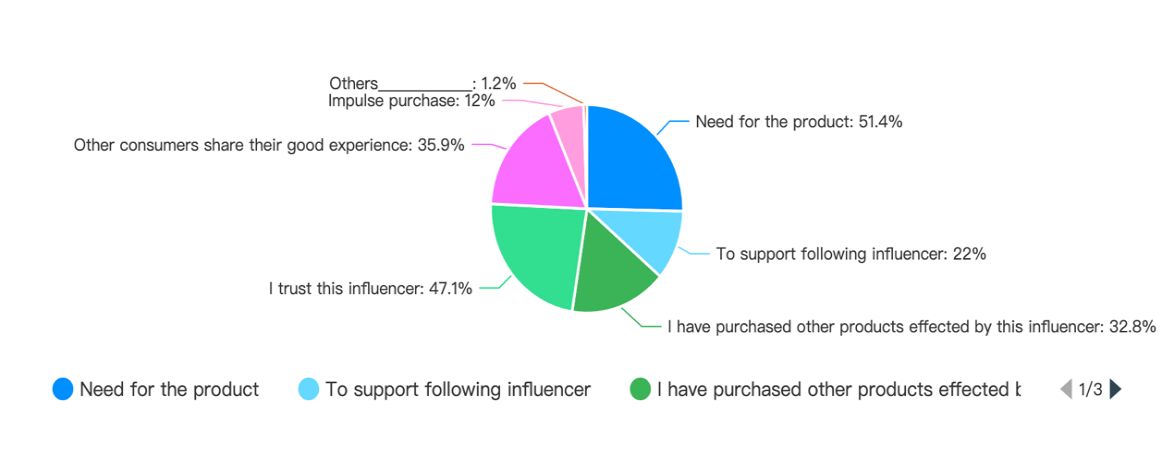

Moreover, the reason for an influencer-motivated purchase shows that 51.4% of responders need the product and 47.1% of responders purchased for the SMI's credibility.

Rather than merely focusing on SMIs' endorsement effectiveness, reasons were collected among responders who were not willing to purchase any products recommended by SMIs. For example, in 37 responders who answered why they did not buy the product recommended by an SMI, 19% of responders claimed that they do not trust the recommendation of SMIs, and 19% of responders illustrated that the product price would be higher if an SMI recommended it.

The widespread effect of advertising and consumer culture, characterized by increasing speed, fragmentation, and subject decentering, leads to the development of ad-avoidance tactics that secure the consumer's psychological space by filtering out excess advertisement clutter [21]. As a result, consumers tend to choose and decide by themselves. Once they knew that the SMI's recommendation was a kind of advertising. Hence, such recommendation makes consumers feel a threat to their freedom, and they will reject this persuasive message, and a boomerang effect occurs [22,23].

Figure 6: Reason for influencer-motivated purchase.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Practical Implications

Instead of the fixed ad cost of traditional media, the influencer marketing budget can vary greatly depending on the company goals, industry, targeted platforms, posting frequency, and other factors. [24]. Hence, it is crucial to identify the right SMI for different campaigns or brands. According to \( {H_{1}},{ H_{2}} \) and \( {H_{3}} \) , there are significant differences in consumer behaviour of males and females. A company could achieve its campaign goal more efficiently by collaborating with SMIs of the same gender and age as its target audience demographic. Moreover, people following more SMIs tend to spend more time and money on the products which SMIs recommended. Hence, it is a particle conclusion when the company aims to find the right target audience on different social media platforms.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

In China, the traditional commercial marketing pattern has been changed, and new e-commerce patterns, like live streaming marketing, have emerged. From celebrities to government staff to corporate leaders participating in a live streaming room to promote products, the economic effect of live streaming has grown steadily [19]. However, this study merely illustrated the relationships between SMIs and followers on the short-video function on Douyin. The live streaming function shows an entirely different scenario than the relationship between SMIs and followers or even users more synchronously and interactively. Hence, a solid and comprehensive understanding of SMIs in live steaming marketing is needed in further studies.

References

[1]. Seno, D., & Lukas, B. A. (2007). The equity effect of product endorsement by celebrities: A conceptual framework from a co-branding perspective. European Journal of Marketing. https://doi-org.proxy.library.nyu.edu/10.1108/03090560710718148

[2]. Spry, A., Pappu, R., & Cornwell, T. B. (2011). Celebrity endorsement, brand credibility and brand equity Ambushing: A meta-analytic review of the influence on sponsorship-linked marketing View project HMP-Authenticity View project. Article in European Journal of Marketing, 45(6), 882-909. https://doi-org.proxy.library.nyu.edu/10.1108/03090561111119958

[3]. Lipiner, B. (2020). What Is Influencer Marketing? An Industry on the Rise · Babson Thought & Action. Retrieved from https://entrepreneurship.babson.edu/what-is-influencer-marketing/

[4]. Carrillat, F. A., & Ilicic, J. (2019). The celebrity capital life cycle: A framework for future research on celebrity endorsement. Journal of Advertising, 48(1), 61–71.

[5]. Jin, S. A. A., & Phua, J. (2014). Following celebrities' tweets about brands: The impact of twitter-based electronic word-of-mouth on consumers' source credibility perception, buying intention, and social identification with celebrities. Journal of Advertising, 43(2), 181–195.

[6]. Torres, P., Augusto, M., & Matos, M. (2019). Antecedents and outcomes of digital influencer endorsement: An exploratory study. Psychology &Amp; Marketing, 36(12), 1267-1276. doi: 10.1002/mar.21274

[7]. Freberg, K., Graham, K., McGaughey, K., & Freberg, L. (2011). Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relations Review, 37(1), 90-92. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.11.001

[8]. TikTok - Wikipedia. (2022). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TikTok

[9]. Statista Global Consumer Survey (GCS). (2022). Social media: Douyin users in China. Statista Global Consumer Survey (GCS). Retrieved from https://www-statista-com.proxy.library.nyu.edu/study/94969/social-media-douyin-in-china-brand-report/

[10]. Nascimento, T.C.D., Campos, R.D. and Suarez, M. (2020), “Experimenting, partnering and bonding: a framework for the digital influencer-brand endorsement relationship”, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 36 Nos 11/12, pp. 1-22.

[11]. Geraghty, G. and Conway, A. (2016) The Study of Traditional and Non-traditional Marketing Communications: Target Marketing in the Events Sector. Paper presented at the 12th Annual Tourism and Hospitality Research in Ireland Conference, THRIC 2016, 16th and 17th June, Limerick Institute of Technology.\

[12]. Chen, K., Lin, J., & Shan, Y. (2021). Influencer marketing in China: The roles of parasocial identification, consumer engagement, and inferences of manipulative intent. Journal Of Consumer Behaviour, 20(6), 1436-1448. doi: 10.1002/cb.1945

[13]. Knoll, J., & Matthes, J. (2017). The effectiveness of celebrity endorsements: A meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0503-8

[14]. Eagly, A.H. (1987), Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation, Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

[15]. Wolin, L.D. (2003), “Gender issues in advertising: an oversight synthesis of research: 1970-2002”, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 43 No. 1, pp. 111-130.

[16]. Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73.

[17]. Rubin, A.M., Perse, E.M. and Powell, R.A. (1985), “Loneliness, parasocial interaction, and local television news viewing”, Human Communication Research, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 155-180.

[18]. Horton, D. and Wohl, R.R. (1956), “Mass communication and para-social interaction”, Psychiatry, Vol. 19 No. 3, pp. 215-229.

[19]. Wang, L., Wang, Z., Wang, X., & Zhao, Y. (2021). Assessing word-of-mouth reputation of influencers on B2C live streaming platforms: the role of the characteristics of information source.

[20]. Newsom (2020). Psy 521/621 Univariate Quantitative Methods. Retrieved 2 September 2022, from https://web.pdx.edu/~newsomj/uvclass/ho_chisq.pdf

[21]. Rumbo, J. (2002). Consumer resistance in a world of advertising clutter: The case ofAdbusters. Psychology And Marketing, 19(2), 127-148. doi: 10.1002/mar.10006

[22]. Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. New York, NY: Academic Press.

[23]. Moyer-Guse ́, E. (2008). Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Communication Theory, 18, 407–425. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00328.x

[24]. Influencer Marketing (2020), “Influencer rates: how much do influencers really cost in 2020?”, available at: https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-rates/

Cite this article

Yan,N. (2023). Interaction between social media influencers (SMI) and followers with different demographic characteristics: Understanding user’s behavior on Douyin short-video platform in China. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,10,149-158.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Business and Policy Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Seno, D., & Lukas, B. A. (2007). The equity effect of product endorsement by celebrities: A conceptual framework from a co-branding perspective. European Journal of Marketing. https://doi-org.proxy.library.nyu.edu/10.1108/03090560710718148

[2]. Spry, A., Pappu, R., & Cornwell, T. B. (2011). Celebrity endorsement, brand credibility and brand equity Ambushing: A meta-analytic review of the influence on sponsorship-linked marketing View project HMP-Authenticity View project. Article in European Journal of Marketing, 45(6), 882-909. https://doi-org.proxy.library.nyu.edu/10.1108/03090561111119958

[3]. Lipiner, B. (2020). What Is Influencer Marketing? An Industry on the Rise · Babson Thought & Action. Retrieved from https://entrepreneurship.babson.edu/what-is-influencer-marketing/

[4]. Carrillat, F. A., & Ilicic, J. (2019). The celebrity capital life cycle: A framework for future research on celebrity endorsement. Journal of Advertising, 48(1), 61–71.

[5]. Jin, S. A. A., & Phua, J. (2014). Following celebrities' tweets about brands: The impact of twitter-based electronic word-of-mouth on consumers' source credibility perception, buying intention, and social identification with celebrities. Journal of Advertising, 43(2), 181–195.

[6]. Torres, P., Augusto, M., & Matos, M. (2019). Antecedents and outcomes of digital influencer endorsement: An exploratory study. Psychology &Amp; Marketing, 36(12), 1267-1276. doi: 10.1002/mar.21274

[7]. Freberg, K., Graham, K., McGaughey, K., & Freberg, L. (2011). Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relations Review, 37(1), 90-92. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.11.001

[8]. TikTok - Wikipedia. (2022). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TikTok

[9]. Statista Global Consumer Survey (GCS). (2022). Social media: Douyin users in China. Statista Global Consumer Survey (GCS). Retrieved from https://www-statista-com.proxy.library.nyu.edu/study/94969/social-media-douyin-in-china-brand-report/

[10]. Nascimento, T.C.D., Campos, R.D. and Suarez, M. (2020), “Experimenting, partnering and bonding: a framework for the digital influencer-brand endorsement relationship”, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 36 Nos 11/12, pp. 1-22.

[11]. Geraghty, G. and Conway, A. (2016) The Study of Traditional and Non-traditional Marketing Communications: Target Marketing in the Events Sector. Paper presented at the 12th Annual Tourism and Hospitality Research in Ireland Conference, THRIC 2016, 16th and 17th June, Limerick Institute of Technology.\

[12]. Chen, K., Lin, J., & Shan, Y. (2021). Influencer marketing in China: The roles of parasocial identification, consumer engagement, and inferences of manipulative intent. Journal Of Consumer Behaviour, 20(6), 1436-1448. doi: 10.1002/cb.1945

[13]. Knoll, J., & Matthes, J. (2017). The effectiveness of celebrity endorsements: A meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0503-8

[14]. Eagly, A.H. (1987), Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation, Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

[15]. Wolin, L.D. (2003), “Gender issues in advertising: an oversight synthesis of research: 1970-2002”, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 43 No. 1, pp. 111-130.

[16]. Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73.

[17]. Rubin, A.M., Perse, E.M. and Powell, R.A. (1985), “Loneliness, parasocial interaction, and local television news viewing”, Human Communication Research, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 155-180.

[18]. Horton, D. and Wohl, R.R. (1956), “Mass communication and para-social interaction”, Psychiatry, Vol. 19 No. 3, pp. 215-229.

[19]. Wang, L., Wang, Z., Wang, X., & Zhao, Y. (2021). Assessing word-of-mouth reputation of influencers on B2C live streaming platforms: the role of the characteristics of information source.

[20]. Newsom (2020). Psy 521/621 Univariate Quantitative Methods. Retrieved 2 September 2022, from https://web.pdx.edu/~newsomj/uvclass/ho_chisq.pdf

[21]. Rumbo, J. (2002). Consumer resistance in a world of advertising clutter: The case ofAdbusters. Psychology And Marketing, 19(2), 127-148. doi: 10.1002/mar.10006

[22]. Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. New York, NY: Academic Press.

[23]. Moyer-Guse ́, E. (2008). Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Communication Theory, 18, 407–425. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00328.x

[24]. Influencer Marketing (2020), “Influencer rates: how much do influencers really cost in 2020?”, available at: https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-rates/