1. Introduction

Beth E. Meyerowitz and Shelly Chaiken examined the framing hypothesis in a study. The study found that different degrees of persuasion were obtained to convince women to engage in breast self-examination (BSE) by emphasizing the hazards and advantages of not doing so.

Their prediction that persuasive arguments emphasizing the negative implications of non-compliance would be more potent than arguments emphasizing the positive effects of implementing BSE was validated. The constraint, in this case, is the presumption that completing a BSE is a risk-seeking behavior and that refraining from performing a BSE is a risk-averse behavior [1]. When arguments are made to emphasize the benefits of continuing with BSE, women may understand them as relative gains from a neutral reference point, the widely held belief that there is no cancer [2].

The researchers then recruited about 90 female college students to participate in the experiment. The subjects worked in groups of three to eight and were randomly assigned to one of four conditions. In the lab, a female experimenter introduced issues to a "healthy attitude" survey and asked them to complete background questionnaires [1]. The first survey is a 34-item Monitor Blunter scale [3], the second is a 20-item Trait Anxiety Scale [4], and the next two are a 13-item Social Desirability Scale [5] and 16-item Health Opinion Survey [6], respectively. In a fifth questionnaire, the individuals were then asked to indicate how frequently they had done a BSE throughout the previous year. After completing the questionnaires, it was determined through several measures, data collection, and analysis that a negative framing emphasizing the potential risks of not implementing BSE was more likely to persuade subjects to enter BSE than a positive framing underlining the advantages of doing so.

According to Levin, Schneider, and Gaeth, the experiment shows that the framing used by information to state the behavior outcome or goal affects the information's ability to persuade. The goal-framing effect is the name given to this phenomenon [7].

Three goal framing can be identified: hedonic, gain, and normative [8]. Hedonic goal framing considers emotional and self-improvement factors. People wish to change their subjective emotions.

A gain goal framing relates to significant personal resources like money [8, 9].

The normative goal framing, concerned with individually or socially acceptable norms like commonly accepted behavioral patterns [8, 9].

This essay will discuss the use of goal framing and highlight its advantages over other framing effects. First and foremost, its goal is to encourage the same favorable or unfavorable outcomes. Second, positive and negative frames are discussed here. Positive framing emphasizes the advantages of doing something. The negative frame, in contrast, highlights the potential loss if the thing is not finished [10].

2. Methodology

Currently, researchers mainly explain the goal framing effect through prospect theory, psychological reactance theory, dual-process theory, and regulatory focus theory.

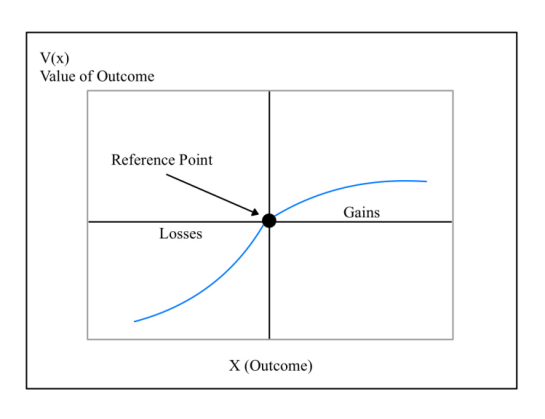

2.1. Prospect Theory

The prospect theory is behavioral economics and behavioral finance theory that Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky created in 1979 [11]. Loss aversion, which demonstrates that agents experience losses far more profoundly than equal benefits, is the cornerstone of prospect theory. Its core idea is that individuals determine their utility by assessing their "gains" and "losses" about a specific benchmark. Every individual has a distinct "reference point". In contrast to what rational agents would do, decisions are therefore made in terms of relative values rather than absolute values [12, 13].

According to the prospect theory, the goal framing effect is caused by individuals' different risk attitudes in the face of gains and losses under different risk perceptions [7]. Specifically, if he is faced with a loss situation, he is more likelier to seek danger and perform this behavior. At this point, a negative framing message that emphasizes the loss of not implementing is more convincing than a positive framing message that underscores the gain of implementing. However, when individuals perceive performing a specific behavior as risk-free or low-risk, positive framing information that emphasizes the benefits of performing is more convincing than negative framing information that highlights the losses of not acting.

2.2. Psychological Reactance Theory

Brehm proposed the psychological reactance theory, believing that individuals always expect to have certain freedom when doing something. When such freedom is threatened, psychological reactance will be generated to maintain or rebuild such freedom [11].

Therefore, when a piece of certain persuasive information is threatened by the perception of their freedom of action, individuals will have psychological reactance and tend to refuse to accept it, which weakens the persuasiveness of the information [14].

Negative framing can produce danger for people to produce more psychological reactance [15]. Therefore positive goal framing is more accessible than negative goal framing of information expression to let people accept it. However, the negative framing will be more persuasive than the positive framing [7, 16] when the individual in the decision-making process of negative deviation will make people pay more attention to the negative information.

Nan introduced negative bias based on psychological reactance theory to clarify this paradoxical phenomenon. He thought that negative prejudice and psychological reactance were in direct competition. Positively framed information is more persuasive than negatively framed information when the resistance tendency is strong. When a person's tendency to resist is low, the information presented in a negative frame will be more persuasive [15].

2.3. Dual-Process Theory

The mechanism of the goal framing effect is further examined using the dual-process theory based on the information processing process. Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) and Heuristic Systematic Model are the most prominent of them (HSM).

According to ELM, people receive information regarding persuasion in two largely separate ways. One uses the "middle fire route" mode, which makes decisions after carefully analyzing the data. Contrarily, the edge route model employs simple contextual indicators (such as emotional information, attractiveness, and source authenticity) to examine data and make conclusions [17]. Although HSM focuses more on how motivation affects a person's information processing than ELM does, it is generally compatible with ELM [18].

The double processing theory states that the system processing mode will be used to process the information when individual motivation is high. The negative framing information is persuasive at this moment because it has greater weight in the individual central policy. When motivation is lacking, people's ability to analyze information systematically is inhibited and heuristic processing mode takes over. Information framed positively nowadays is persuasive since it is simpler to encourage people's favorable attitudes about information.

2.4. Regulatory Focus Theory

Higgins established the regulatory focus theory, which divided individual regulatory orientation into promotion and prevention focus to emphasize the interaction between people and framing information. The first examines if it is possible to achieve Japanese norms, while the second examines whether it can prevent undesirable outcomes [19]. The regulatory Fit theory is based on the idea that when people with different regulatory orientations use their preferred behavioral strategies, regulatory matching will be achieved. [20].

Additionally, some researchers have noted that the description of the frame information rather than the valence of the information determines how well the frame information matches the regulatory orientation [21].

Because goal framing effect positive framing of information not only can be described as "profit," can also be described as "avoid losses," negative information framing can be described as a "loss," can also be described as "to give up interest," so when the emphasis is to be a positive framing information behavior to avoid losses, to the prevention of orientation are more persuasive; However, when the negative framing message emphasizes that not doing a particular behavior means the individual gives up the benefit, it is more persuasive to the person who holds the promotion orientation [21].

3. Applications about HIV and CO2

3.1. Application 1: HIV Testing

Anne Marie Apanovitch, Danielle McCarthy, and Peter Salovey investigated whether perceptions of the certainty of HIV test results affected the effectiveness of framing information that focused on the advantages of getting an HIV test (gain-framed) or the costs of not getting an HIV test (loss-framed) in their study encouraging low-income minority women to test for HIV [22].

The researchers made videos in Spanish and English and translated the two languages into each other for 531 participants. And the four sets of educational videos with the same content but different frames. The goal is to make the argument the same in each video.

In the baseline experiment, women were asked to watch randomly assigned videos and answer in their preferred language in one-on-one interviews at 3, 6, and 9 months after data collection.

Here is a sample of how the two examples in the video are constructed. Moreover, they are all accompanied by a picture of a couple hugging on a couch [23, 24].

Gain and desirable (gain frame): You may receive many positive things and experience the peace of mind that comes from knowing health status if tested for HIV.

Not attain and undesirable (loss frame): You may not reap many positive outcomes and have the peace of mind that comes from knowing the health status if you choose not to get tested for HIV.

Gain and undesirable (loss frame): You may have adverse outcomes and have more anxiety of worrying the potential health problems if you are not tested for HIV.

Not attain and undesirable (gain frame): You may not encounter many problems and be less anxious that comes from knowing health status if tested for HIV.

The participant's age, race, income, religious affiliation, prior HIV testing, or baseline willingness to accept HIV did not change between the four video conditions, according to chi-square tests and analyses of variance (all ps>.20). But following the two Post videos, baseline's goals change. Initial results showed that he couldn't test for HIV positive individuals (M = 2.94, SD = 1.30), in contrast to those who believed they could (M = 3.45, SD = 1.07), F (1, 467) = 18.63, p.001. possesses a weaker baseline intent.

Last, they found that positive framing messages of gain were more likely to encourage HIV testing than negative framing messages of loss for subjects who believed they were at low risk of testing positive. Furthermore, for subjects who thought they were at higher risk of testing positive, negative framing messages were more likely to encourage them to get tested [25-27].

Table 1: Means and standard deviations for self-reported variables across conditions.

Variable n M (range) or % SD | |||

Baseline intentions | 480 | 3.11 | 1.25 |

Post video intentions | 473 | 3.65 | 1.02 |

Perceived certainty | 471 | 1.66 | 0.39 |

Objective risk | |||

-Unprotected sex acts in past 30 days | 480 | 7.08 (0-300) | 19.12 |

-STD history | 480 | 51.2% | |

-IDU history | 479 | 5.0% | |

Number of partners | |||

-Past 30 days | 480 | 0.84 (0-20) 4.6%>1 | 1.17 |

-Past year | 480 | 3.17 (1-602) 27.7%>1 | 28.92 |

-Lifetime | 479 | 14.22 (1-999) 29.4%>9 | 67.12 |

Partner riska | |||

-Had an STD | 477 | 2.19 54.7%>1 | 1.37 |

-Injected drugs | 478 | 1.60 24.1%>1 | 1.23 |

-Been in prison | 477 | 3.04 71.3%>1 | 1.62 |

-Had sex with men | 474 | 1.33 15.6%>1 | 0.90 |

Notes: STD=sexually transmitted disease; IDU=injection drug use.

a Items relating to partner risk were scored on a 5-point scale, with one being the least likely and five being the most likely.

Table 1 from Apanovitch, Anne & Mccarthy, Danielle & Salovey, Peter. (2003). Using message framing to motivate HIV testing among low-income, ethnic minority women. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association.

Table 2: Self-Reported HIV testing behavior predicted by a hierarchical logistic regression model within six months of message exposure.

Predictor variable | b | SE | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | Δx2 |

Step 1 Previous HIV testing | 0.20*** | 0.04 | 1.22 | 1.13, 1.32 | 36.54***a |

Step 2 Previous HIV tesing Baseline intentions | 0.14*** 0.49*** | 0.04 0.10 | 1.15 1.63 | 1.07, 1.24 1.33, 1.98 | 26.02***a |

Step 3 Previous HIV testing Baseline intentions Post video intentions | 0.15*** 0.18 0.59* | 0.04 0.14 0.20 | 1.16 1.20 1.81 | 1.08, 1.25 0.92, 1.56 1.22, 2.69 | 9.41**a |

Step 4 Previous HIV testing Baseline intentions Post video intentions Certainty Message framing Framing * Certainty | 0.16*** 0.15 0.61** 0.88* 0.63* -1.05* | 0.04 0.14 0.21 0.35 0.29 0.47 | 1.17 1.16 1.85 2.41 1.87 0.35 | 1.09, 1.27 0.89, 1.53 1.23, 2.76 1.22, 4.76 1.07, 3.28 0.14, 0.88 | 7.98*b |

Final Model | 79.95***c |

Notes: For all chi-squares, N=419. *p< .05. **p< .01. ***p< .001. a df=1. b df=3. c df=6

Table 2 from Apanovitch, Anne & Mccarthy, Danielle & Salovey, Peter. (2003). Using message framing to motivate HIV testing among low-income, ethnic minority women. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association.

The term "message framing" here refers to the various ways researchers convey information. However, it is also goal framing. The various ways that information is provided results in various outcomes, but the objective to have women tested for HIV remains the same.

3.2. Application 2: CO2 Emission

The study evaluated and contrasted carbon dioxide emissions by using goal framing. The researchers made the difference in CO2 emissions from various means of transportation more apparent to people by using both positive and negative frames [28].

The carbon dioxide emissions per passenger for bicycles, full-size cars, and sports utility vehicles over a five-mile distance are used to compare emissions. Furthermore, they weigh 132 grams, 500 grams, and 3400 grams. They employed the following four sets of phrases on a sample of 194 adults between the ages of 19 and 76 (with a 39-year-old average age).

Gain framing and loss framing made up the first set. Set 1's gain framing is that mode X generates 500g of carbon dioxide for a 5-mile trip while mode Y produces 368g less, while set 1's loss framing is that mode X produces 132g of carbon dioxide for a 5-mile trip while mode Y produces 368g more. Additionally, the second set will be split into gain and loss framing. In set 2, the gain framing is that mode X generates 3400g of carbon dioxide for a 5-mile trip, and mode Y produces 2900g fewer, but in this set, the loss framing is that mode X produces 500g of carbon dioxide for the same distance, and mode Y produces 2900g more.

First, statistically, the proportion of participants who judged the mode of transportation as "extremely different" increased significantly in both Settings. Second, the statistics were remarkably similar despite being compared at various carbon dioxide concentrations. Finally, the second group showed a more substantial negative framing effect [29-31].

Finally, the researchers found that using the negative framing was more effective than using the positive framing to make people aware of the differences in the amount of carbon dioxide emitted by different travel modes and thus was more likely to influence people's choice of travel mode.

Figure 1: A hypothetical value function.

Table 3: Gain and loss framing for two comparison sets of CO2 emissions.

Set 1 (132g against 500g) |

For comparison set 1, gain framing: |

A 5-mile trip in Mode X results in 500g of CO2 emissions. |

Mode Y produces 368 g less than mode A. |

For comparison set 1, loss framing: |

A 5-mile trip in Mode X results in 132g of CO2 emissions. |

Mode Y produces 368g more than mode X. |

Set 2 (500g against 2400g) |

For comparison set 2, gain framing: |

A 5-mile trip in Mode X results in 3400g of CO2 emissions. |

Mode Y produces 2900g less than mode A. |

For comparison set 2, loss framing: |

A 5-mile trip in Mode X results in 3400g of CO2 emissions. |

Mode Y produces 2900g more than mode X. |

Notes: Table 3 from Avineri, Erel & Waygood, Edward. (2022). Applying goal framing to enhance the effect of information on transport-related CO 2 emissions.

4. Limitations and Future Outlooks

Goal framing is often influenced by the source credibility, behavior types, emotions and other factors.

Firstly, one of the key variables impacting the impact of goal framing is source credibility. Generally speaking, information with a positive framing is more persuasive when it is highly credible, whereas information with a negative framing is more persuasive when it is less credible. Jones, Sinclair, and Courneya found that when the information was more credible, students who read the positive framing information were more motivated to engage in physical activity and continued to engage in physical activity more often on subsequent tests. In contrast, the negative framing information was more repulsive [32].

According to prospect theory, people with different risk probabilities will show different goal framing effects. This difference mainly manifests in detection and prevention behavior [33]. Prevention is generally seen as no risk.

Thirdly, positive framing information is more persuasive because, according to certain studies, people experiencing good emotions are more receptive to peripheral cues and tend to absorb information heuristically. However, people tend to pay attention to and analyze information systems when they are in a state of negative emotional arousal, making them more open to accepting the information offered by the negative framing [34].

It is challenging for researchers to run studies without interference from outside factors in light of the enumeration and explanation of the effectiveness of goal framing provided above.

For future research on goal framing, other external factors that can influence the effectiveness of goal framing, such as personality and environment, can be explored. At the same time, methods to enhance the effectiveness of goal framing are also worth further exploration. At present, studies on the goal framing effect are all about grouping subjects into groups and presenting them with a specific type of framing information respectively, and then determining whether there is a goal framing effect by comparing the adoption rate of subjects' behaviors after reading positive framing information and negative framing information. However, in real life, the information received by individuals is often not a particular type of frame information but the interweaving of multiple frame information.

5. Conclusion

Goal framing exists everywhere in our lives. It influences how people think and changes their decisions. Of course, the goal framing effect also has many limitations because it is difficult for people to achieve that in a whole situation, which means guiding behavior without any interference from other information and only influenced by goal framing. Based on the information description, which leads to different information impact effects, Prospect theory, psychological reactance theory, Dual-process theory, and Regulatory focus theory explain the goal framing effect. This paper also gives two practical applications of goal framing, through which people further understand how the goal framing effect affects people's decision-making through information representation and the actual situation.

References

[1]. Meyerowitz, B. E., & Chaiken, S. (1987). The effect of message framing on breast self-examination attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 500–510.

[2]. Weinstein, N. D. (1982). Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems. Journal of behavioral Medicine, 5, 441-460.

[3]. Miller, S. M. (1981). Predictability and human stress: Toward a clarification of evidence and theory. In L. Berkowtiz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 14, pp. 204-256). New York: Academic Press.

[4]. Spielberger, C. D. (1972). Anxiety: Current trends in theory and research (Vol. 1). New York: Academic Press.

[5]. Reynolds, W. M. (1982). Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 8, 199-125.

[6]. Krantz, D. S., Baum, A., & Wideman, M. V. (1980). Assessment of preferences for self-treatment and information in health care. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 977-990.

[7]. Levin I P, Schneider S L & Gaeth G J. All frames are not created equal: A typology and critical analysis of framing effects. Orginazational behavior and Human Decision Processes, 1998, 76: 149-188.

[8]. Lindenberg, S., & Steg, L. (2007). Normative, gain and hedonic goal frames guiding environmental behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 63(1), 117-137.

[9]. Lindenberg, S. (2008). Social Rationality, Semi-Modularity and Goal-Framing: what is it all about?. Analyse & Kritik, 30(2), 669-687

[10]. Joan Meyers-Levy and Durairaj Maheswaran (1990) ,"Message Framing Effects on Product Judgments", in NA - Advances in Consumer Research Volume 17, eds. Marvin E. Goldberg, Gerald Gorn, and Richard W. Pollay, Provo, UT : Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 531-534.

[11]. Brehm J W. A theory of psychological reactance. New York: Academic Press, 1966.

[12]. Barberis, Nicholas; Heung, Ming; Thaler, Richard H. (2006). "Individual preferences, monetary gambles, and stock market participation: a case for narrow framing". American Economic Review. 96 (4): 1069–1090

[13]. Cartwright, E. (2018). behavioral Economics (3rd ed.). Routledge.

[14]. Kihara K & Osaka N. Early mechanism of negativity bias: An attentional blink study. Japanese Psychological Research, 2008, 50: 1-11

[15]. Nan X L. Does psychological reactance to loss-framed messages dissipate the negativity bias? An investigation of the message framing effect. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, TBA, San Francisco, CA, 2007, May.

[16]. McCormick M & Seta J J. Lateralized goal framing: How selective presentation impacts message effectiveness. Journal of Health Psychology,2012, 17: 1099-1109.

[17]. Petty R E & Cacioppo J T. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Psychology, 1986, 19: 124-203.

[18]. Chaiken S, Liberman A & Early A. H. Heuristic and systematic information processing within and beyond the persuasion context. In J. S. Ulemana & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), Unintended Thought. New York: Guilford Press, 1989: 212-252.

[19]. Higgins E T. Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 1997, 52: 1280-1300.

[20]. Higgins E T. Making a good decision: Value from fit. American Psychologist, 2000, 55: 1271-1230.

[21]. Meyer-Levy J & Maheswaran D. Exploring message framing outcomes when systematic, heuristic, or both types of precessing occur. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2004, 14: 159-167.

[22]. Banks, S. M., Salovey, P., Greener, S., Rothman, A. J., Moyer, A., Beauvais, J., & Epel, E. (1995). The effects of message framing on mammography utilization. Health Psychology, 14, 178–184.

[23]. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1982). The psychology of preferences. Scientific American, 246, 160–170.

[24]. Kalichman, S. C., & Coley, B. (1995). Context framing to enhance HIV antibody-testing messages targeted to African American women. Health Psychology, 14, 247–254.

[25]. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decisions under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291.

[26]. Rothman, A. J., Salovey, P., Antone, C., Keough, K., & Martin, C. (1993). The influence of message framing on intentions to perform health behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 29, 408–433.

[27]. Apanovitch, Anne & Mccarthy, Danielle & Salovey, Peter. (2003). Using message framing to motivate HIV testing among low-income, ethnic minority women. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association.

[28]. Coulter, A., Elwyn, G., Chatterton, T. And Musselwhite, C. B. A. (2007). Exploring public attitudes to personal carbon dioxide emission information.

[29]. Gaker, D., Vautin, D., Vij, A., and Walker, J.L. (2011). The power and value of green in promoting sustainable transport behavior. Environmental Research Letters 6, 034010.

[30]. Gaker, D., Zheng, Y. and Walker, J. (2010). Experimental economics in transportation. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2156, 47-55.

[31]. Gonzales, M.H., Aronson, E. and Costanzo, M.A. (1988). Using social cognition and persuasion to promote energy conservation: a quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 18(12), 1049-1066.

[32]. Jones L W, Sinclair R C & Courtney K S. The effects of source credibility and message framing on exercise intentions, behaviors, and attitudes: An integration of the elaboration likelihood model and prospect theory, 2003, 33: 176-196.

[33]. Rothman A J & Salvoes P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: The role of message framing, 1997, 121: 3-19.

[34]. Tong E M W, Tan C R M, Latheef N A, et al. Conformity: Moods matter, 2008, 38: 601-611.

Cite this article

Gu,R. (2023). A Holistic Introduction of Goal Framing. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,13,168-176.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Business and Policy Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Meyerowitz, B. E., & Chaiken, S. (1987). The effect of message framing on breast self-examination attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 500–510.

[2]. Weinstein, N. D. (1982). Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems. Journal of behavioral Medicine, 5, 441-460.

[3]. Miller, S. M. (1981). Predictability and human stress: Toward a clarification of evidence and theory. In L. Berkowtiz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 14, pp. 204-256). New York: Academic Press.

[4]. Spielberger, C. D. (1972). Anxiety: Current trends in theory and research (Vol. 1). New York: Academic Press.

[5]. Reynolds, W. M. (1982). Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 8, 199-125.

[6]. Krantz, D. S., Baum, A., & Wideman, M. V. (1980). Assessment of preferences for self-treatment and information in health care. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 977-990.

[7]. Levin I P, Schneider S L & Gaeth G J. All frames are not created equal: A typology and critical analysis of framing effects. Orginazational behavior and Human Decision Processes, 1998, 76: 149-188.

[8]. Lindenberg, S., & Steg, L. (2007). Normative, gain and hedonic goal frames guiding environmental behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 63(1), 117-137.

[9]. Lindenberg, S. (2008). Social Rationality, Semi-Modularity and Goal-Framing: what is it all about?. Analyse & Kritik, 30(2), 669-687

[10]. Joan Meyers-Levy and Durairaj Maheswaran (1990) ,"Message Framing Effects on Product Judgments", in NA - Advances in Consumer Research Volume 17, eds. Marvin E. Goldberg, Gerald Gorn, and Richard W. Pollay, Provo, UT : Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 531-534.

[11]. Brehm J W. A theory of psychological reactance. New York: Academic Press, 1966.

[12]. Barberis, Nicholas; Heung, Ming; Thaler, Richard H. (2006). "Individual preferences, monetary gambles, and stock market participation: a case for narrow framing". American Economic Review. 96 (4): 1069–1090

[13]. Cartwright, E. (2018). behavioral Economics (3rd ed.). Routledge.

[14]. Kihara K & Osaka N. Early mechanism of negativity bias: An attentional blink study. Japanese Psychological Research, 2008, 50: 1-11

[15]. Nan X L. Does psychological reactance to loss-framed messages dissipate the negativity bias? An investigation of the message framing effect. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, TBA, San Francisco, CA, 2007, May.

[16]. McCormick M & Seta J J. Lateralized goal framing: How selective presentation impacts message effectiveness. Journal of Health Psychology,2012, 17: 1099-1109.

[17]. Petty R E & Cacioppo J T. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Psychology, 1986, 19: 124-203.

[18]. Chaiken S, Liberman A & Early A. H. Heuristic and systematic information processing within and beyond the persuasion context. In J. S. Ulemana & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), Unintended Thought. New York: Guilford Press, 1989: 212-252.

[19]. Higgins E T. Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 1997, 52: 1280-1300.

[20]. Higgins E T. Making a good decision: Value from fit. American Psychologist, 2000, 55: 1271-1230.

[21]. Meyer-Levy J & Maheswaran D. Exploring message framing outcomes when systematic, heuristic, or both types of precessing occur. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2004, 14: 159-167.

[22]. Banks, S. M., Salovey, P., Greener, S., Rothman, A. J., Moyer, A., Beauvais, J., & Epel, E. (1995). The effects of message framing on mammography utilization. Health Psychology, 14, 178–184.

[23]. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1982). The psychology of preferences. Scientific American, 246, 160–170.

[24]. Kalichman, S. C., & Coley, B. (1995). Context framing to enhance HIV antibody-testing messages targeted to African American women. Health Psychology, 14, 247–254.

[25]. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decisions under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291.

[26]. Rothman, A. J., Salovey, P., Antone, C., Keough, K., & Martin, C. (1993). The influence of message framing on intentions to perform health behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 29, 408–433.

[27]. Apanovitch, Anne & Mccarthy, Danielle & Salovey, Peter. (2003). Using message framing to motivate HIV testing among low-income, ethnic minority women. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association.

[28]. Coulter, A., Elwyn, G., Chatterton, T. And Musselwhite, C. B. A. (2007). Exploring public attitudes to personal carbon dioxide emission information.

[29]. Gaker, D., Vautin, D., Vij, A., and Walker, J.L. (2011). The power and value of green in promoting sustainable transport behavior. Environmental Research Letters 6, 034010.

[30]. Gaker, D., Zheng, Y. and Walker, J. (2010). Experimental economics in transportation. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2156, 47-55.

[31]. Gonzales, M.H., Aronson, E. and Costanzo, M.A. (1988). Using social cognition and persuasion to promote energy conservation: a quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 18(12), 1049-1066.

[32]. Jones L W, Sinclair R C & Courtney K S. The effects of source credibility and message framing on exercise intentions, behaviors, and attitudes: An integration of the elaboration likelihood model and prospect theory, 2003, 33: 176-196.

[33]. Rothman A J & Salvoes P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: The role of message framing, 1997, 121: 3-19.

[34]. Tong E M W, Tan C R M, Latheef N A, et al. Conformity: Moods matter, 2008, 38: 601-611.