1. Introduction

The 1980s marked the inception of the information and communication technology (ICT) revolution, accompanied by swift advancements in the Internet domain. These developments paved the way for the emergence of numerous sizable Internet-based enterprises, such as Amazon and Google. The sheer volume can allow these companies to gain significant market power to influence the price of their products or services. Verticals, however, have many different links throughout the production process, commonly known as upstream and downstream. In general, vertical market power is the ability of a company to influence the price of upstream or downstream companies throughout the entire chain. In light of the considerable vertical market power wielded by online platforms, this article aims to examine the range of issues arising from this power, explore the means of assessing these issues through quantitative and qualitative measures, and propose effective solutions to address them.

2. Problems Caused by Vertical Market Power

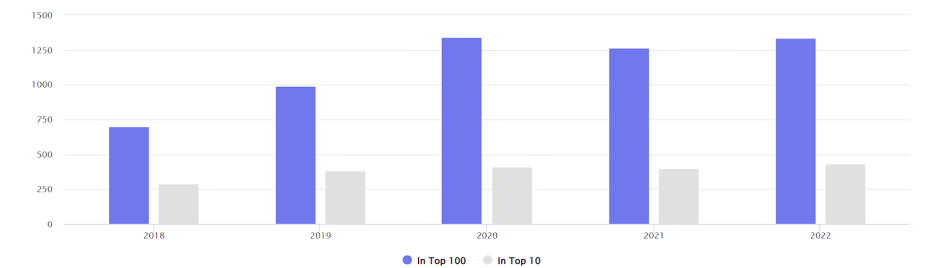

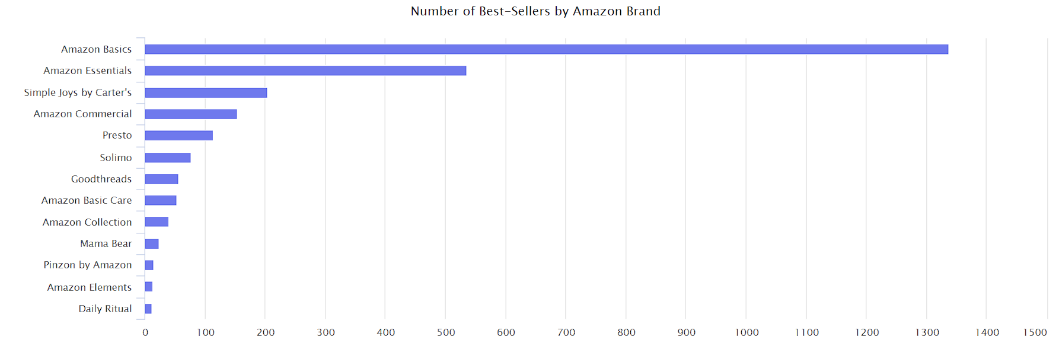

The primary issue with Amazon is unfair competition. E-commerce platforms, like Amazon Marketplace, are commonly multi-faceted, wherein buyers stand to gain from a more significant number of sellers available on the platform. Meanwhile, sellers seek to join a platform that provides access to a vast customer base. This results in network externalities and economies of scale, enabling a competitive edge for the platform. According to Table 1 from Marketplace Pulse, Amazon's website in the US had 2.2 billion visits in February 2023 alone [1]. In addition, it is clear from Amazon's published 2022 proxy that today's Amazon works with over 2 million independent partners in the US, including sellers, developers, content creators, authors, and delivery providers [2]. These staggering figures reveal that today Amazon has grown into an online platform giant, with several areas of involvement that have further expanded its market power. Nonetheless, these platforms are prone to exhibiting bias towards their own products or services, such as prioritised display in product search results, in contrast to those of third-party sellers. Furthermore, third-party sellers incur advertising costs on the platform, while the platform's products do not bear such costs. For example, Amazon can collect sales data on third-party products and use it to enter profitable market segments for its proprietary brands and compete with third-party suppliers without buying products as a traditional retailer or sharing data with other brands [3]. As can be seen from Figure 1, Amazon Basics has 1338 best-sellers in 2022 [4]. Best-sellers are products in the top 100 in any category or subcategory on Amazon. Figure 2 shows that Amazon has private-label brands in various industries. These private labels enjoy the dividends of the platform itself and have an inherent advantage when competing with third-party sellers. The cost savings can make the products more cost-effective. The brand value of Amazon itself can also make users unconsciously trust the free brand when they see that it is a private label and are influenced by the Halo effect. These advantages would put third-party sellers in unfair competition.

Table 1: Amazon.com traffic by country in February 2023 [1].

Website | Traffic in February 2023 |

amazon.com (US) | 2.2b |

amazon.co.jp (Japan) | 533m |

amazon.de (Germany) | 408m |

amazon.co.uk (UK) | 328m |

amazon.in (India) | 286m |

amazon.it (Italy) | 160m |

amazon.fr (France) | 153m |

amazon.com.br (Brazil) | 152m |

Figure 1: Number of Amazon Basics Best-Sellers [4].

Figure 2: Number of Best-Sellers by Amazon Brand [4].

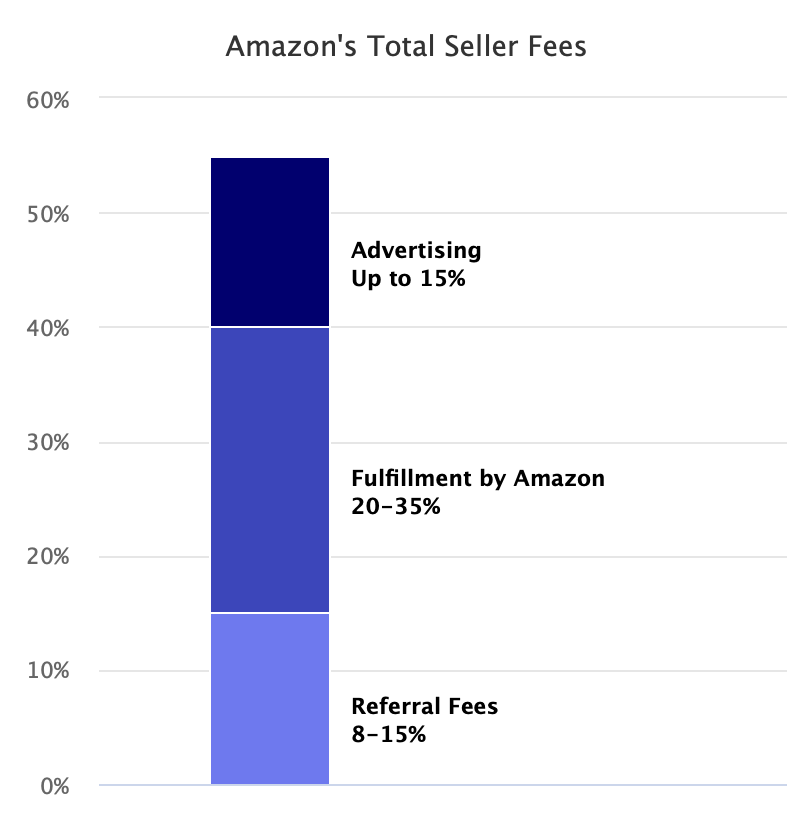

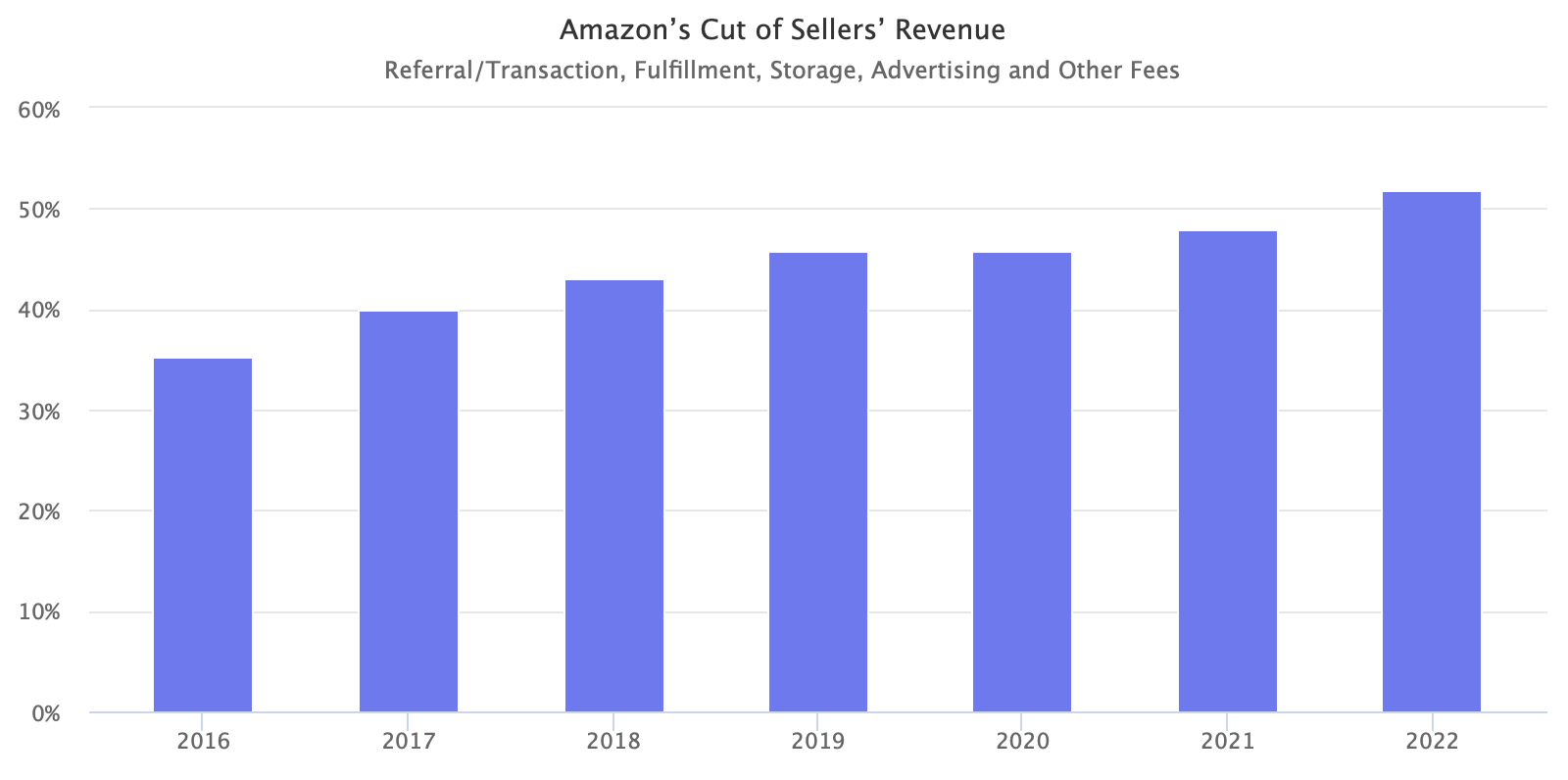

The range of bundled services that Amazon offers to third-party sellers, such as payment processing, shipping and customer service, can also lead to platform providers having more control over sellers. Nowadays, Amazon tries to create an ecosystem that offers a range of services to its customers. AWS, Amazon's extensive cloud platform for both buyers and sellers, provides a range of cloud services, such as elastic computing, storage, databases, and IoT, aimed at helping businesses minimise their IT investment and maintenance expenses. In 2019, AWS generated $35 billion in annual revenue, and its revenue grew by 30% in 2020 [5]. Amazon also offers shipping and delivery services, including same-day and next-day delivery, through its vast network of warehouses and fulfilment centres, further tying it to sellers. According to a study in Marketplace Pulse (Figure 3), the typical Amazon seller pays 15% in transaction fees (which Amazon calls sales commissions), 20-35% in Amazon logistics fees (including storage and other expenses), and up to 15% in Amazon advertising and promotion fees. Total costs vary by category, product price, size, weight and the seller's business model [6]. From Figure 4, we can see that the percentage of sales paid by Amazon sellers is increasing yearly, and by 2022 it will have exceeded 50%. These huge fees burden sellers, and they have to raise prices to maintain their meagre net margins.

Figure 3: Amazon’s Toral Seller Fees [6].

Figure 4: Amazon’s Cut of Sellers’ Revenue (Referral/Transaction, Fulfillment, Storage, Advertising and Other Fees) [6].

Amazon has offered bundles to platform sellers while expanding its brands as well, and in 2017 Amazon acquired Whole Foods for $13.4 billion, the first significant acquisition in Amazon's history. The Austin, Texas-based supermarket, founded in 1978, is the world's premier natural and organic food supermarket and was the first in the US to have organic certification. The deal not only gave Amazon the Whole Foods brand but also buried a network of more than 460 prime shipping locations where Whole Foods is located. Not only has Amazon made a splash in the food market, but on 26 May 2021, it announced the acquisition of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, commonly known as MGM, which was founded in 1924 and rose to prominence during the Hollywood era with the rights to more than 400 films and 17,000 TV shows, for US$8.45 billion [7]. A tremendous help to its own Amazon Prime Video. These acquisitions show that Amazon is reaching out to all walks of life, using the influence of these markets to feed back into itself and further enhance its market power. These market forces from other markets can help Amazon improve its own production chain and increase its vertical market power over upstream and downstream companies in this segment of the online platform as a way to gain more profit.

Amazon has also been accused of using its power to negotiate lower prices with suppliers. In early 2010, for example, Amazon had control of around 90% of the e-book market, but the then Big Six book publishing company was at odds. The publisher argued that Amazon's pricing for e-books was unreasonably low, fearing that Amazon's pricing practices were undermining consumer perceptions of the value of its products and undermining demand for its more profitable new books, hardcovers and print products. Before 2010, publishers charged Amazon a fixed fee for wholesale eBooks, but when publishers increased this wholesale price, Amazon responded by maintaining its retail prices and adopting a loss-making strategy. Subsequently, even though several publishers tried "window" distribution, they could not push Amazon to raise the cost of their ebooks. At this point, Amazon had enormous power to take a hard line on any e-book and retaliate against individual publishers, disrupting their physical book sales [8]. Amazon's prescribed terms and conditions for these suppliers act as a shackle that allows its vertical market power to be amplified indefinitely, potentially leading to suppliers receiving a squeeze on their profits. Sellers encounter the vertical market power wielded by the platform but need help to switch to a different platform due to the high costs involved. For example, a favorable reputation on eBay results in higher seller prices [9]. However, transferring such reputations from one platform to another is challenging, further augmenting the platform's vertical market power. These forces can confer upon Amazon the capability to impose higher fees or practice discriminatory measures against certain sellers, thereby diminishing competition. Consequently, buyers may need more high-quality products or encounter elevated prices.

The vertical market power held by Amazon can also give rise to data privacy and security concerns. For example, Amazon maintains a record of consumers' product purchases, which can be utilised to analyse their individual price preferences and product needs. As a result, the platform highlights products highly likely to be purchased in a prominent position on its homepage, thereby increasing the likelihood of these products being bought and sellers spending money on advertising for them. At the same time, the platform can engage in price discrimination. The more comprehensive the data, the higher the likelihood of achieving First-degree price discrimination, which can increase social welfare. However, it is noteworthy that consumer surplus may gradually diminish, thereby jeopardising consumers' interests and causing apprehension among users concerning privacy and security.

3. Measuring the Vertical Market Power of Amazon

3.1. Quantitative Aspects

When assessing the vertical market power of online platforms, regulators can employ quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative measures may include various indicators, one of which is market share. Companies with a high market share are more likely to hold greater market power and have the potential to engage in anti-competitive behaviours. For example, in 2021, Amazon will have annual sales of $ 469.8 billion, compared to $ 7.43 billion for the same type of online platform eBay, a whopping 63 times more than eBay. In addition, Amazon's advertising business is thriving, with sales approaching $ 40 billion in 2022, a tenfold increase in five years by the end of 2022 [5][10]. Much of this growth comes from more network coverage; for example, brands that don't sell on Amazon, such as restaurants and hotels, can also advertise on its live streaming platform Twitch, which sits on the same ad network. This impressive growth rate has led Amazon to go all out to chase Google and Facebook. In comparison, Google's advertising revenue, including all Google properties and YouTube, grow by just 2.5% to $ 54.4 billion in 2022. Combined with the Amazon acquisitions of Whole Foods and MGM mentioned above, Amazon's market share and the number of areas it covers make it a "behemoth". The dramatic market shares observed among these online platforms indicate their formidable market power. As per EU law, substantial market shares give rise to a presumption of dominance by a single company.

The second quantitative measure relates to the pricing level, where regulators can compare product or service prices on a platform concerning prices observed in other markets. The platform's employment of market power to bolster profits can be inferred from the price rise over time. For example, a survey conducted in the first quarter of 2022 (Figure 5) revealed that 40% of US consumers choose to shop at Amazon mainly because of the platform's low shipping costs; this US consumer share is followed by fast shipping at 37%, affordable product prices at 36% and Prime membership at 36% [11]. As can be seen from this data, Amazon's prices are lower than other online platforms. These low prices mainly originate from third-party sellers but help Amazon enhance its platform’s brand value and image. An example of a price comparison indicator is observed in the toy market, where Amazon's pricing behaviour following the exit of Toys R Us (a prominent physical retailer specialising in toys and baby products) was assessed. Amazon experienced a price increase of approximately 5%, reducing its original pricing advantage by half. Although Amazon continues to offer relatively low prices, consumer benefits are expected to diminish further with the rise of more brick-and-mortar retailers. If online prices remain low, consumers may be willing to forgo the chance to browse and evaluate products as physical retailers continue to disappear [12]. Combined with the previously mentioned year-on-year increase in fees charged by Amazon to third parties, the range of examples of pricing power held by the e-book market confirms that Amazon has unparalleled vertical market pricing power and derives higher margins from it.

Figure 5: Reasons why US consumers will choose Amazon to shop in 2022 [11].

The third point is the barriers to entry and switching costs. High barriers to entry may result in fewer competitors in the market and greater market power for those companies already in the market. As mentioned earlier, Amazon's AWS today allows it to build a solid barrier to entry in this area of the web platform, as illustrated by its year-on-year revenue growth. Conversion costs are even easier to find on Amazon. Reputation is often platform-specific, as the user’s reputation is a function of the number of transactions already carried out on the platform [13]. Best-sellers on Amazon find it challenging to give up their already well-established product image, and the switching costs of changing platforms are unacceptable to them. Not only is it difficult to convert the product image of third-party sellers, but bundled services add to this cost. According to research by Marketplace Pulse, over 90% of Best-sellers on Amazon use FBA storage services [4]. Amazon's FBA logistics and storage system demonstrates the significant control it already has over its supply chain. Consumers also have switching costs. For example, when consumers decide to use another platform, they have to get used to the new terms and processing of transactions, etc. [13]. The sheer volume of visitors to Amazon's website shapes exaggerated network externalities, and these indirect network effects add to the switching costs for third-party sellers and buyers.

3.2. Qualitative Aspects

Qualitative measures can commence with evaluating the customer experience. One approach could be establishing survey panels to gauge customer perception of the quality of products and services on the platform and assess if they feel they have sufficient options. For instance, a certain number of random buyers on Amazon can be questioned regularly regarding their experience using the platform. Moreover, in evaluating the vertical market power of online platforms, it is essential to consider the perspective of sellers. Data collection can be done to understand how Amazon treats its sellers, such as examining whether they are subjected to unfair fees or terms and the degree of ease with which they can switch to another platform. Lastly, the level of innovation can be evaluated to determine if the dominant player, Amazon, is limiting the entry of new, innovative products or services, thus reducing competition. Considering these aspects necessitates a comprehensive assessment of Amazon's impact on the market.

4. Some Sensible Solutions

Several countries, including the US, EU, India, China, and others, have implemented competition laws to curb the monopolistic tendencies of large companies in their respective domains. These regulations can mandate divestment of business segments, unbundling or denying the power of dominant platforms. For instance, platform providers may be required to separate their platform business from product sales to mitigate the potential adverse effects of bundled services. Additionally, equal treatment for sellers and reduced switching costs for them can enhance competition. Several European countries, for example, have launched separate investigations into MFN treatment, this time directly involving Amazon, concerning the imposition of MFN clauses in distribution agreements between Amazon and publishers and sellers on the Amazon marketplace, which could lead to an abuse of a dominant position [3]. The MFN clauses, for example, require publishers to offer Amazon terms similar to or better than those provided to their competitors and to notify Amazon of more favorable or substitute terms offered to them by Amazon's competitors, such as distribution models [14]. These terms may lead to less consumer choice, less innovation and higher prices. Other European competition regulators have therefore prosecuted Amazon for the price evaluation terms enforced on the Amazon marketplace platform [15]. These competition laws and competition regulators could limit Amazon's vertical market power to some extent and protect the interests of third-party sellers and buyers. Regarding Amazon's vertical integration through mergers, competition law can be reviewed when it acquires its upstream and downstream industries for multiple market and business line expansions. An example is the case of Amazon's acquisition of potential rivals Zappos and Diapers.com, which was allegedly the result of a predatory threat previously made by Amazon, which, after attempting to acquire them, open competing shops and sold goods at a loss, forcing both companies to eventually sell to it [16]. Competition regulators can scrutinise such acquisitions when they occur to see if this acquisition will allow Amazon to gain a dominant position, driving out smaller competitors through the exclusionary behaviour of predatory pricing strategies.

The subsequent course of action should involve enhancing transparency by mandating Amazon to furnish more details about its pricing, terms, and data practices to decrease the likelihood of problems such as discrimination, downgrading, or misuse of data by Amazon. In addition, regulators can enforce disclosure requirements regarding the algorithms used to rank products and data usage and restrict Amazon from selling user information. The third measure involves promoting competition by facilitating the development of alternative platforms to break Amazon's monopoly, incentivising innovation. Lastly, consumer protection can be strengthened by requiring Amazon to implement measures to prevent the sale of counterfeit products or to provide enhanced security for consumers who purchase products or services. This can encourage competition and improve the overall consumer experience on the platform.

5. Conclusion

Amazon's sheer size has allowed it to gain incredible vertical market power. However, these vertical market forces can lead to unfair competition, making it more expensive for third-party sellers to compete with Amazon's brands. This is followed by a series of bundled services that make the situation worse for third-party sellers, who, even in the face of high fees, are unable to switch to a new platform due to the enormous switching costs associated with being deeply tied to Amazon on AWS, FBA and other services. In addition, Amazon's upstream and downstream acquisitions and expansion into other markets have further increased its vertical market power, reducing market competition to the detriment of consumers. Finally, data privacy issues can also lead to consumers receiving unfair price discrimination, again hurting consumers. The vertical market power of online platforms, for example, Amazon, can be measured in two main ways, quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative aspects can be considered regarding Amazon's market share, control of pricing power, barriers to entry and conversion to cost. The qualitative aspect can be determined by regular random surveys of the environment of third-party sellers and buyers on the platform to decide whether Amazon has a surprising vertical market power that ultimately leads to a monopoly. The final and potentially effective solution would still be regulation by competition regulators and government intervention to scrutinise Amazon's behaviour in terms of pricing, acquisitions, etc., and to increase transparency further so that more people regulate Amazon’s behaviour, ultimately limiting Amazon's vertical market power. Amazon is a good example of an online platform; other platforms, such as eBay, have problems with vertical market power and can have the example of Amazon as a reference.

References

[1]. Marketplace Pulse: Amazon’s Fastest Growing Markets (2023). https://www.marketplacepulse.com/articles/amazons-fastest-growing-markets.

[2]. Amazon 2022 Proxy statement. https://s2.q4cdn.com/299287126/files/doc_financials/2022/ar/Amazon-2022-Proxy-Statement.pdf.

[3]. Ducci, F.: E-Commerce Marketplaces. In Natural Monopolies in Digital Platform Markets (Global Competition Law and Economics Policy, pp. 76-96). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108867528.004 (2020).

[4]. Marketplace Pulse: Marketplace Pulse Year in Review 2022 (2022). https://www.marketplacepulse.com/year-in-review-2022.

[5]. Amazon 2021 Annual Report https://s2.q4cdn.com/299287126/files/doc_financials/2022/ar/Amazon-2021-Annual-Report.pdf.

[6]. Marketplace Pulse: Amazon Takes a 50% Cut of Seller’s Revenue (2023). https://www.marketplacepulse.com/articles/amazon-takes-a-50-cut-of-sellers-revenue.

[7]. Birkinbine, B., Bilić, P.: The Amazon–MGM Deal. The Political Economy of Communication, 9(2) (2022).

[8]. Flood, Z. C.: Antitrust Enforcement in the Developing E-Book Market: Apple, Amazon, and the Future of the Publishing Industry. Berkeley Technology Law Journal, 31(2), 879–904 (2016). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26377775.

[9]. Melnik MI., Alm J.: Does a seller’s ecommerce reputation matter? Evidence from ebay auctions. J Ind Econ 50:337–349 (2002).

[10]. eBay 2021 Anuual Report https://ebay.q4cdn.com/610426115/files/doc_financials/2021/ar/2021-Annual-Report-(1).pdf.

[11]. Yltaevae L.: Reasons U.S consumers shop at Amazon 2022 (2023). https://www.statista.com/statistics/1311765/reasons-to-shop-on-amazon-united-states/?locale=en.

[12]. He, L., Reimers, I., & Shiller, B.: Does Amazon Exercise Its Market Power? Evidence from Toys“R”Us. The Journal of Law and Economics (2022). https://doi.org/10.1086/720824

[13]. Haucap, J., Heimeshoff, U.: Google, Facebook, Amazon, eBay: Is the Internet driving competition or market monopolization?. Int Econ Econ Policy 11, 49–61 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-013-0247-6

[14]. European Commission, Antitrust: Commission Accepts Commitments from Amazon

[15]. Bundeskartellamt: Amazon Removes Price Parity Obligation for Retailers on Its Marketplace Platform, Case Report B6-46/12 (2013).

[16]. Brad Stone, The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon (New York: Little, Brown, 2013).

Cite this article

Lyu,M. (2023). The Vertical Market Power of Online Platforms Case Study: The Vertical Market Power of Amazon. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,32,98-105.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Economic Management and Green Development

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Marketplace Pulse: Amazon’s Fastest Growing Markets (2023). https://www.marketplacepulse.com/articles/amazons-fastest-growing-markets.

[2]. Amazon 2022 Proxy statement. https://s2.q4cdn.com/299287126/files/doc_financials/2022/ar/Amazon-2022-Proxy-Statement.pdf.

[3]. Ducci, F.: E-Commerce Marketplaces. In Natural Monopolies in Digital Platform Markets (Global Competition Law and Economics Policy, pp. 76-96). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108867528.004 (2020).

[4]. Marketplace Pulse: Marketplace Pulse Year in Review 2022 (2022). https://www.marketplacepulse.com/year-in-review-2022.

[5]. Amazon 2021 Annual Report https://s2.q4cdn.com/299287126/files/doc_financials/2022/ar/Amazon-2021-Annual-Report.pdf.

[6]. Marketplace Pulse: Amazon Takes a 50% Cut of Seller’s Revenue (2023). https://www.marketplacepulse.com/articles/amazon-takes-a-50-cut-of-sellers-revenue.

[7]. Birkinbine, B., Bilić, P.: The Amazon–MGM Deal. The Political Economy of Communication, 9(2) (2022).

[8]. Flood, Z. C.: Antitrust Enforcement in the Developing E-Book Market: Apple, Amazon, and the Future of the Publishing Industry. Berkeley Technology Law Journal, 31(2), 879–904 (2016). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26377775.

[9]. Melnik MI., Alm J.: Does a seller’s ecommerce reputation matter? Evidence from ebay auctions. J Ind Econ 50:337–349 (2002).

[10]. eBay 2021 Anuual Report https://ebay.q4cdn.com/610426115/files/doc_financials/2021/ar/2021-Annual-Report-(1).pdf.

[11]. Yltaevae L.: Reasons U.S consumers shop at Amazon 2022 (2023). https://www.statista.com/statistics/1311765/reasons-to-shop-on-amazon-united-states/?locale=en.

[12]. He, L., Reimers, I., & Shiller, B.: Does Amazon Exercise Its Market Power? Evidence from Toys“R”Us. The Journal of Law and Economics (2022). https://doi.org/10.1086/720824

[13]. Haucap, J., Heimeshoff, U.: Google, Facebook, Amazon, eBay: Is the Internet driving competition or market monopolization?. Int Econ Econ Policy 11, 49–61 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-013-0247-6

[14]. European Commission, Antitrust: Commission Accepts Commitments from Amazon

[15]. Bundeskartellamt: Amazon Removes Price Parity Obligation for Retailers on Its Marketplace Platform, Case Report B6-46/12 (2013).

[16]. Brad Stone, The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon (New York: Little, Brown, 2013).