1. Introduction

In 1997, Thailand's transition from a fixed to a floating exchange rate system triggered the rapid spread of the Asian financial crisis [1]. Thailand, once an economic marvel among Asia's "Four Tigers," bore the brunt of this upheaval, as evidenced by a plummeting GDP growth rate from 5.5% in 1996 to a staggering -10.1% in 1998 [2]. This crisis engulfed numerous nations, raising concerns that China would be the next to succumb. However, China's resilience defied these expectations. Despite facing similar challenges, such as a sharp decline in foreign trade and capital accounts, China maintained an impressive average GDP growth rate of 8.2% from 1997 to 1999 [3]. This paper delves into the reasons behind China's successful navigation through the Asian economic crisis by juxtaposing the macroeconomic policies of China and Thailand with the renowned "Impossible Triangle" macroeconomic theory. This paper therefore uses this comparative case to explore in depth what kind of important role capital controls have in times of economic crisis.

2. The "Impossible Triangle" theory

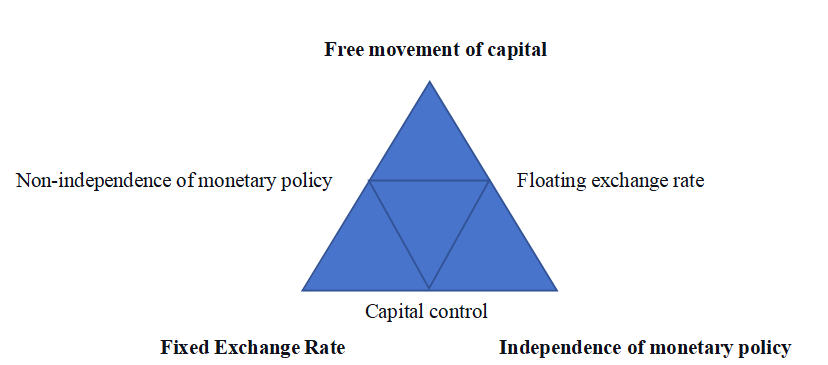

The Impossible Triangle is the theory that in a country's macroeconomic system, the free flow of capital, a fixed exchange rate, and the independence of monetary policy cannot exist together but must coexist in two, as shown in Figure.1[4]. This implies that in each combination there must be an opposing policy to the one not included:

If the choice is to open up free capital flows and a fixed exchange rate, that will necessarily result in monetary policy dependence, which Thailand initially insisted on.

Suppose the free movement of capital and monetary policy independence is chosen. In that case, only a floating exchange rate regime will be accepted, something Thailand was forced to accept under the pressure of the economic crisis.

If an independent monetary policy and a fixed exchange rate were chosen, then capital would have to be controlled, which is what China has insisted on.

Figure 1: Impossible triangle [4]

2.1. Free movement of capital

2.1.1. False prosperity under Thailand's insistence on the free movement of capital

Thailand's economic development is characterized by an excessive relaxation of restrictions on capital flow, which has attracted substantial short-term foreign capital inflows that could potentially render its stability precarious. Since the early 1990s, Thailand has been part of the 'East Asian miracle,' exhibiting an average annual GDP growth rate exceeding 5% [5]. The primary catalyst for its rapid economic expansion lay in the widespread adoption, among ASEAN countries, of the Western capitalist model known as the "fast-track capitalist" economic strategy [3]. The essence of this strategy is to promote unimpeded capital flow through the extensive liberalization of financial markets, thereby attracting significant foreign investments that foster economic growth. In its pursuit of increased foreign investment, the Thai government dismantled various financial controls. Most notably, the establishment of the Bangkok International Bank Facility (BIBF) permitted domestic and foreign banks to engage in nearly tax-free offshore and re-shore activities, including lending in US dollars at rates significantly lower than the baht rate [6]. This channel became the primary conduit for foreign investments into Thailand, particularly in US dollars. By 1996, its size had ballooned to as much as US$50 billion (Ibid).

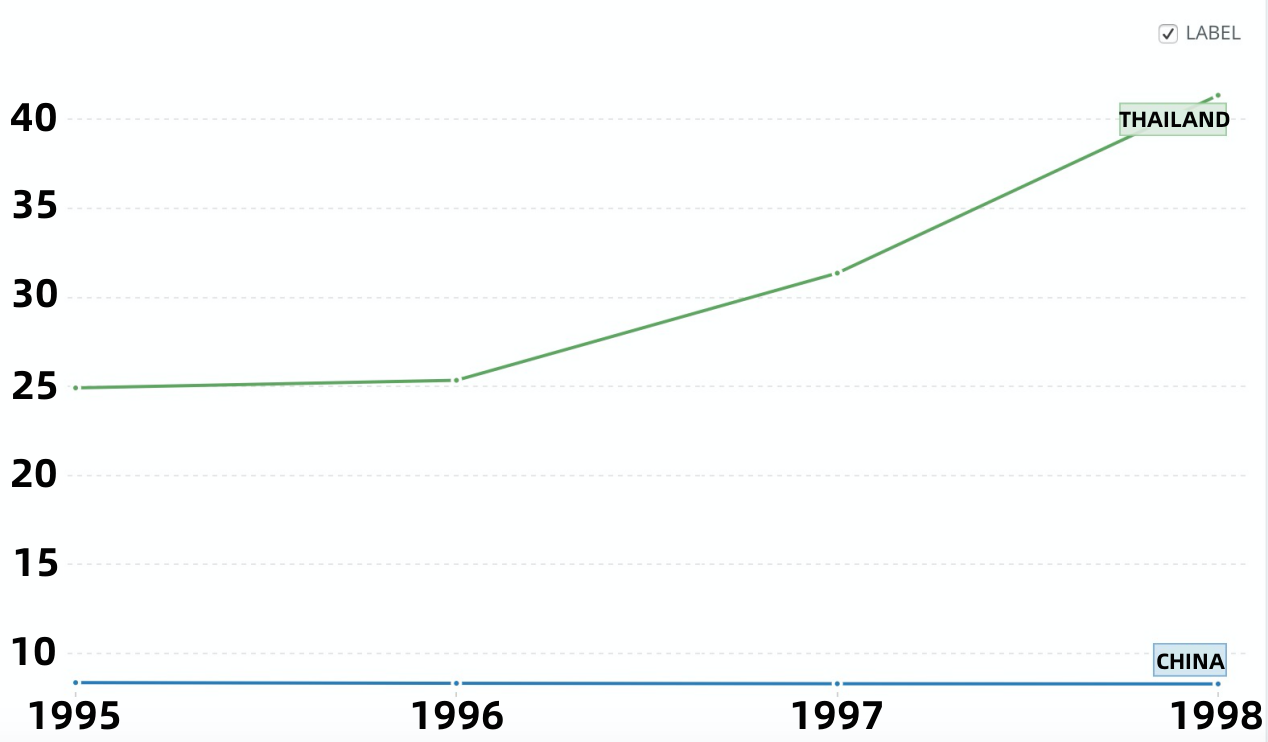

These measures promoting capital flow liberalization rapidly transformed Thailand into an economy heavily reliant on foreign capital, with foreign investments already surpassing domestic savings and investments in contributing to economic development. However, this economic approach, which is overly dependent on foreign investment, is highly unstable, and there are two fundamental reasons for this instability. First, the absence of regulatory measures led to the majority of foreign investments being short-term, driven by the pursuit of significant profits. This resulted in a situation where a substantial portion of unregulated short-term investments flowed into high-return, high-risk, long-term projects such as the real estate sector. Statistics reveal that Thailand accounted for 40% of total bank loans for real estate investment before the crisis [7]. Before reaping long-term benefits, the Thai government had to bear substantial capital costs and the risk of a real estate bubble burst. Second, excessively lax capital inflow restrictions facilitated the unhindered, rapid exit of these funds during times of crisis [6]. This was exemplified by the immediate withdrawal of foreign capital at the onset of the Asian financial crisis, as illustrated in Figure 2, where Thailand's investment-to-GDP ratio sharply declined in 1997 [8]. With the withdrawal of foreign capital, Thailand's foreign capital-dependent economic development model rapidly crumbled, leading to an economic downturn. This also underscores the vulnerability of unregulated financial markets in the face of economic crises.

Figure 2: Exchange Rate between China and Thailand from 1995 to 1998 [9]

2.1.2. China's control of capital markets effectively protects the domestic economy

China's stringent control over capital flows has effectively shielded its economy from the detrimental impacts of external financial crises. In contrast to Thailand's relatively simplistic controls, China has implemented rigorous restrictions on capital movements. This approach finds its roots in the Chinese government's intervention in financial markets, a hallmark of its unique socialist market economy system, known for its efficacy in safeguarding market stability [10]. China's control measures manifest in two primary ways. First, the Renminbi (RMB) is not freely convertible in the capital account due to robust government oversight [3] Consequently, RMB conversion is restricted to current account transactions and necessitates government approval [10]. This mechanism allows for meticulous scrutiny of the nature and quality of foreign investments, enabling the selection of capital types that align with the country's economic development goals rather than indiscriminately absorbing all forms of capital. This is evident in the second point, wherein the majority of investments in China constitute long-term and stable foreign direct investment (FDI), in stark contrast to Thailand's prevalence of short-term inflows [3]. This prudent approach to capital flow management in China prevents the undue concentration of capital in a single industry, as witnessed in Thailand. Furthermore, China has established the State Administration for Foreign Exchange (SAFE) to regulate substantial foreign capital transactions [10]. This regulatory infrastructure ensures that China is less susceptible to a sudden and significant capital outflow-induced liquidity vacuum, which could potentially result in economic paralysis. The contribution of Chinese investment to GDP as a percentage, underscores the stability engendered by China's restrictions on the free flow of capital (Figure 2). This stability remained nearly constant during the crisis, in stark contrast to the situation in Thailand.

2.2. Fixed Exchange Rate Regime

2.2.1. Thailand - adherence to fixed exchange rates

Thailand's insistence on maintaining a fixed exchange rate policy to support the Thai baht's value, despite inadequate international foreign exchange reserves, was fundamentally at odds with sound economic development. This inflexible exchange rate regime is widely recognized as the primary catalyst for the Asian financial crisis [11]. As previously mentioned, Thailand's highly open financial markets at that time exposed it to external financial vulnerabilities. Consequently, the Thai government viewed a less risky fixed exchange rate system as an attractive choice to stabilize the baht's exchange rate.However, Aizenman and Hansamnn contended that the more integrated a domestic market becomes with international markets, the more suitable a flexible floating exchange rate regime becomes [12]. The underlying rationale for this argument was that the Thai government, in their pursuit of economic stability, overlooked the fact that their limited foreign exchange reserves would not suffice to mitigate the risks posed by a volatile global market. By 1997, Thailand held only a few billion dollars in foreign exchange reserves, equivalent to approximately 70% of its short-term debt [13]. The Greenspan-Guidotti rule stipulates that this value should ideally be at least 100% (Ibid). This shortfall in foreign exchange reserves left Thailand ill-equipped to absorb excess baht supply and stabilize the exchange rate in the face of international speculators who borrowed substantial amounts of baht from the Thai government and then hurriedly sold it on the international market.Consequently, as depicted in Figure 2, Thailand's determined efforts to maintain the baht's fixed exchange rate ultimately faltered in 1996, precipitating the outbreak of the Asian financial crisis.

2.2.2. China - Reasonableness of insistence on a fixed exchange rate system

China's steadfast commitment to a fixed exchange rate system served as a shield for its domestic economy, effectively mitigating the wider impact of the 1997 Asian financial crisis that had swept through East Asia. During that tumultuous period, many East Asian currencies, including the Japanese yen and the South Korean won, experienced significant devaluations akin to the Thai baht's plunge. These currency devaluations naturally posed a considerable challenge to China's export competitiveness. By 1998, China's traditional manufacturing exports to East Asia had declined by 10.5%, to Japan by 4.3%, and to South Korea by a significant 30.2% [14]. The Chinese Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation advocated for RMB devaluation to sustain China's export-import momentum [15]. However, the Bank of China (PBC) and the People's Development Council of China (SPC) have emphasized the adverse domestic and international repercussions of a depreciation of the RMB. A domestic RMB devaluation wouldn't be effective in boosting export competitiveness, since a substantial portion of China's exports relied on imported technology and products. Any gains in export competitiveness from RMB devaluation would be offset by increased import costs. Secondly, in the global context, RMB devaluation would exacerbate the competitive devaluation of currencies among East Asian countries, thus triggering a further escalation of the financial crisis [16]. In January 1998, PBC Governor announced China's commitment to maintaining the RMB's fixed exchange rate, which unwavering policy stance played a pivotal role in bolstering the domestic economy and containing the Asian financial crisis. China earned high international praise for its responsible conduct as a major power, with Thailand's Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai and Information Minister George Yeo publicly expressing their gratitude and admiration for China's steadfast refusal to devalue the RMB [10].

Another crucial factor contributing to the successful implementation of the no-devaluation policy was China's substantial foreign exchange reserves. In stark contrast to Thailand's meager reserves, China had amassed a significant pool of international foreign exchange reserves during the crisis. By July 1998, these reserves had reached approximately US$140 billion [12]. This substantial war chest endowed China with the robust capacity to uphold the RMB's exchange rate in the foreign exchange market. International financial speculators found it challenging to target the RMB as they had with the Thai baht. China's ample reserves also alleviated concerns about maintaining a fixed exchange rate, reinforcing the stability of its exchange rate policy.

2.3. Independence of monetary policy

2.3.1. Thailand-Incompatibility of independent interest rate policy with its exchange rate regime

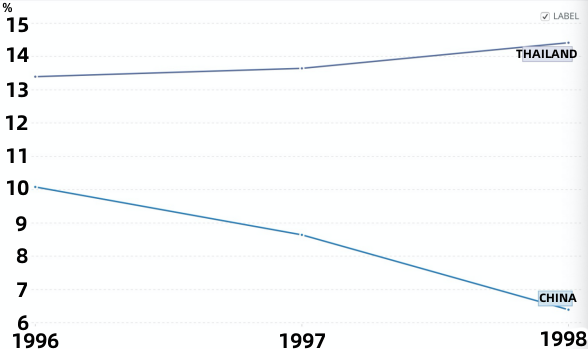

The Thai government's adherence to a fixed exchange rate regime during the crisis aggravated the country's economic woes. Under a fixed exchange rate system, fiscal policy is effective while monetary policy is rendered ineffective, whereas the opposite holds true under a floating exchange rate regime, assuming an open capital and current account with free capital movement [11]. Thailand found itself trapped in this very dilemma. Thailand's extensive unregulated capital liberalization resulted in a preponderance of short-term foreign debt investments, fostering a pattern of borrowing from abroad and lending domestically to finance turnovers. By 1996, foreign debt had ballooned to half of Thailand's GDP and a staggering 123% of exports [17]. This surge in low-quality investment debt compelled Thai banks to issue substantial non-performing loans to sustain the credit boom [7]. With mounting pressure on commercial banks and foreign capital exiting the country, the ability of the domestic economy to drive domestic demand dwindled.This necessitated the swift implementation of an expansionary monetary policy, encompassing interest rate cuts, increased money supply, and a lowered exchange rate to stimulate investment and exports. However, the imperative to maintain a stable peg to the US dollar and alleviate domestic credit strains compelled authorities to raise interest rates, as evidenced in Chart 3. Lending rates surged from 13% in 1996 to 14.4% in 1998, deposit rates from 10.3% to 10.6%, and interbank lending rates from 11% to 20% [17]. While this move temporarily stabilized inflation and mitigated the risk of domestic financial institutions collapsing, it further strained the fragile Thai economy.Ultimately, when besieged by international speculators and confronted with massive foreign capital outflows, Thailand found itself unable to service its substantial foreign debts.

2.3.2. China - The independence of monetary policy

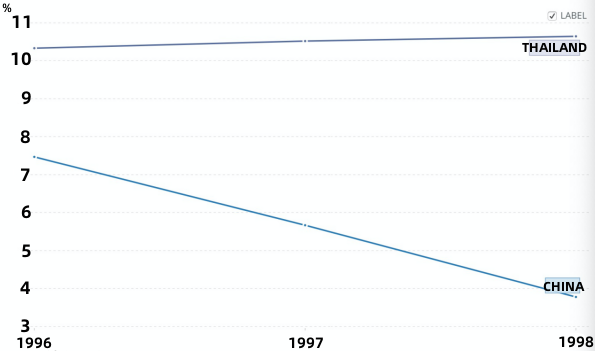

China's adept management of capital flow regulations has allowed it to effectively navigate economic crises and stabilize its domestic economy. China smoothly executed an expansionary monetary policy during the crisis to alleviate export pressures and combat deflation resulting from the devaluation of neighboring currencies [18]. China's robust capital controls during this period deterred foreign capital from easily entering its market. Furthermore, China's commitment to a fixed exchange rate for the Renminbi (RMB) diminished foreign direct investment (FDI) interest. In 1997, FDIs contributed 11.2% to China's economic growth, but this figure dwindled to a mere 0.07% by 1998 [3]. Consequently, China grappled with worsening domestic economic challenges, witnessing a decline in real economic growth from 9.7% in 1996 to 7.8% two years later. Concurrently, issues of unemployment and inflation exacerbated. Addressing these concerns necessitated the implementation of an expansionary monetary policy aimed at stimulating investment and consumption, bolstering domestic demand to counterbalance the withdrawal of FDIs. Consequently, the People's Bank of China (PBC) initiated a series of lending rate reductions from 1997 onward. As depicted in Figure 3 (a) and (b), China's lending rates dropped from 10.1% to 6.4%, while deposit rates decreased from 7.5% to 3.8%. Additionally, in 1998, a deposit reserve system was introduced, earmarking substantial reserves to ensure timely withdrawal by depositors for investment and consumption purposes [18]. Crucially, China's capital controls acted as a robust barrier against external currency market turbulence affecting its domestic currency. This pivotal factor facilitated the smooth implementation of these monetary policies, promoting economic development within China.

Figure 3: China and Thai deposit and loan interest rates change. Lending interest rates and Deposit interest rates between China and Thailand from 1996 to 1998 [9] (a)Lending interest rates; (b)Deposit interest rates

3. Analysis

Firstly, Thailand's pursuit of economic liberalization, devoid of robust regulatory measures, left it exposed to financial vulnerability due to the influx of lower-quality foreign capital during its economic boom. In contrast, China boasts a well-established regulatory system governing the type, quality, and flow of capital, resulting in healthier capital flows that acted as a buffer against external economic crises.

Secondly, Thailand's unwavering commitment to a fixed exchange rate regime, while neglecting the regulation of its exchange rate, rendered it susceptible to speculative attacks by international actors, ultimately precipitating an economic crisis. Conversely, China, equipped with ample foreign exchange reserves, steadfastly maintained a fixed exchange rate, effectively insulating itself from the contagion of the crisis.

Ultimately, Thailand's combination of capital liberalization and a fixed exchange rate system hindered its ability to independently implement effective monetary policy, given the incongruence between its domestic economic conditions and currency valuation. In contrast, China's judicious blend of capital controls and a fixed exchange rate enabled the seamless execution of monetary policy, fostering stable domestic economic development. In essence, Thailand's miscalculation of its domestic economic landscape and an imprudent amalgamation of macroeconomic policies precipitated the financial crisis, while China's more rational policy mix played a pivotal role in containing the propagation of the Asian economic crisis and upholding domestic economic stability.

4. Conclusion

This study delves into the divergent macroeconomic strategies of Thailand and China, focusing on capital liberalization, fixed exchange rates, and monetary policy autonomy through the lens of the impossible triangle framework. It is important to note that the research scope of this paper is confined to three specific variables—exchange rate regime, monetary policy, and free capital flows—employed for a comparative analysis of the two countries within the context of the impossible triangle theory. However, we do not extensively explore certain external environmental variables, such as differences in regional policies and the activities of multinational enterprises, as they are not the primary focus of this investigation. Although these factors undeniably impact the main variables under scrutiny, this paper deliberately avoids in-depth exploration in these areas. It is crucial to recognize that a more specific, topic-oriented study may be necessary to comprehensively consider the influence of these external variables. Therefore, the conclusions of this study should be interpreted with caution, and future research is encouraged to delve more deeply into these external factors within a broader context.

References

[1]. Aizenman, J., & Hausmann, R. (2000). Exchange rate regimes and financial-market imperfections.

[2]. Bello, W. (1999) ‘THE ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISIS: Causes, dynamics, prospects’, Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 4(1), pp. 33–55. doi:10.1080/13547869908724669.

[3]. Girardin, E., Lunven, S. & Ma, G. (2017) China's evolving monetary policy rule: From inflation-accommodating to anti-inflation policy, The Bank for International Settlements. Available at: https://www.bis.org/publ/work641.htm (Accessed: January 1, 2023).

[4]. Jansen, K. (2001) ‘Thailand, Financial Crisis and Monetary Policy’, Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 6(1), pp. 124–152. doi:10.1080/13547860020024567.

[5]. Kim, Y. (1999) ‘The Asian Financial Crisis: Causes, Cures, and Ssytemic Implications’, Growth and Change, 30(1), p. 148.

[6]. Liew, Leong H. (2004) ‘Policy Elites in the Political Economy of China’s Exchange Rate Policymaking’, Journal of Contemporary China, 13(38), pp. 21–51. doi:10.1080/1067056032000151328.

[7]. Liew, L. (1999) ‘The Impact of the Asian Financial Crisis on China: The Macroeconomy and State-owned Enterprise Reform’, MIR: Management International Review, 39(4), pp. 85–104.

[8]. Xu, Z. (2018) ‘China’s exports, export tax rebates and exchange rate policy’, World Economy, 41(5), pp. 1288-1308–1308. doi:10.1111/twec.12570.

[9]. World Bank Open Data (1998). ‘Deposit and Lending Interest Rate - China and Thailand’ and ‘Exchange Rate - China and Thailand’ .Available at: https://www.data.worldbank.org (Accessed: January 1, 2023).

[10]. Maroney, N., Naka, A. and Wansi, T. (2004) ‘Changing Risk, Return, and Leverage: The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis’, Journal of Financial & Quantitative Analysis, 39(1), pp. 143–166. doi:10.1017/S0022109000003926.

[11]. Prommawin, B. (2013) ‘International Reserves Adequacy Analysis: The Optimal Level for Thailand’, International Journal of Intelligent Technologies & Applied Statistics, 6(2), pp. 145–169. doi:10.6148/IJITAS.2013.0602.04.

[12]. Shalendra D. Sharma (2020) ‘Why China Survived the Asian Financial Crisis?’, Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, 22(2), pp. 225–252. doi:10.1590/0101-31572002-1235.

[13]. Sheel, A. (2014) ‘A Monetary Policy Rule for Emerging Market Economies: The Impossible Trinity and the Taylor Rule’, Economic and Political Weekly, 49(4), pp. 39–42.

[14]. Sufian, F. & Habibullah, M.S. (2009) ‘The Impact of Asian Financial Crisis on Bank Performance: Empirical Evidence Form Thailand and Malaysia’, Savings and Development, 33(2), pp. 153–181.

[15]. Xi C.. The impact of further opening of economy on macrofinance and countermeasures--an analysis based on the theory of "impossible triangle"[J]. Future and Development,2017,41(10):54-61.

[16]. Xiong, P. & Wang, F (2006) ‘The Choice of Exchange Rate Regime Based on the Affecting Factors of Exchange Rate Regime: A Theoretical Review’, Journal of Guangdong University of Finance, 21(1), pp. 17–22. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-1625.2006.01.003.

[17]. Wade, R. (2000) ‘WHEELS WITHIN WHEELS: Rethinking the Asian Crisis and the Asian Model’, Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), p. 85. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.85.

[18]. Wang H. (1999) ‘The Asian financial crisis and financial reforms in China’, Pacific Review, 12(4), p. 537.

Cite this article

Li,H. (2024). A Comparison of the Macroeconomic Systems in China and Thailand under Impossible Triangle Theory. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences,71,163-169.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Business and Policy Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Aizenman, J., & Hausmann, R. (2000). Exchange rate regimes and financial-market imperfections.

[2]. Bello, W. (1999) ‘THE ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISIS: Causes, dynamics, prospects’, Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 4(1), pp. 33–55. doi:10.1080/13547869908724669.

[3]. Girardin, E., Lunven, S. & Ma, G. (2017) China's evolving monetary policy rule: From inflation-accommodating to anti-inflation policy, The Bank for International Settlements. Available at: https://www.bis.org/publ/work641.htm (Accessed: January 1, 2023).

[4]. Jansen, K. (2001) ‘Thailand, Financial Crisis and Monetary Policy’, Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 6(1), pp. 124–152. doi:10.1080/13547860020024567.

[5]. Kim, Y. (1999) ‘The Asian Financial Crisis: Causes, Cures, and Ssytemic Implications’, Growth and Change, 30(1), p. 148.

[6]. Liew, Leong H. (2004) ‘Policy Elites in the Political Economy of China’s Exchange Rate Policymaking’, Journal of Contemporary China, 13(38), pp. 21–51. doi:10.1080/1067056032000151328.

[7]. Liew, L. (1999) ‘The Impact of the Asian Financial Crisis on China: The Macroeconomy and State-owned Enterprise Reform’, MIR: Management International Review, 39(4), pp. 85–104.

[8]. Xu, Z. (2018) ‘China’s exports, export tax rebates and exchange rate policy’, World Economy, 41(5), pp. 1288-1308–1308. doi:10.1111/twec.12570.

[9]. World Bank Open Data (1998). ‘Deposit and Lending Interest Rate - China and Thailand’ and ‘Exchange Rate - China and Thailand’ .Available at: https://www.data.worldbank.org (Accessed: January 1, 2023).

[10]. Maroney, N., Naka, A. and Wansi, T. (2004) ‘Changing Risk, Return, and Leverage: The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis’, Journal of Financial & Quantitative Analysis, 39(1), pp. 143–166. doi:10.1017/S0022109000003926.

[11]. Prommawin, B. (2013) ‘International Reserves Adequacy Analysis: The Optimal Level for Thailand’, International Journal of Intelligent Technologies & Applied Statistics, 6(2), pp. 145–169. doi:10.6148/IJITAS.2013.0602.04.

[12]. Shalendra D. Sharma (2020) ‘Why China Survived the Asian Financial Crisis?’, Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, 22(2), pp. 225–252. doi:10.1590/0101-31572002-1235.

[13]. Sheel, A. (2014) ‘A Monetary Policy Rule for Emerging Market Economies: The Impossible Trinity and the Taylor Rule’, Economic and Political Weekly, 49(4), pp. 39–42.

[14]. Sufian, F. & Habibullah, M.S. (2009) ‘The Impact of Asian Financial Crisis on Bank Performance: Empirical Evidence Form Thailand and Malaysia’, Savings and Development, 33(2), pp. 153–181.

[15]. Xi C.. The impact of further opening of economy on macrofinance and countermeasures--an analysis based on the theory of "impossible triangle"[J]. Future and Development,2017,41(10):54-61.

[16]. Xiong, P. & Wang, F (2006) ‘The Choice of Exchange Rate Regime Based on the Affecting Factors of Exchange Rate Regime: A Theoretical Review’, Journal of Guangdong University of Finance, 21(1), pp. 17–22. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-1625.2006.01.003.

[17]. Wade, R. (2000) ‘WHEELS WITHIN WHEELS: Rethinking the Asian Crisis and the Asian Model’, Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), p. 85. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.85.

[18]. Wang H. (1999) ‘The Asian financial crisis and financial reforms in China’, Pacific Review, 12(4), p. 537.