1. Introduction

Claude Monet, a painter who dedicated his life on paint landscapes and people’s lives, was also the pioneer of Impressionism, leading French painting in the second half of the 19th century [1]. He rose to prominence after the publication of Impression, Sunrise (Figure 1) in 1872, and has become a master of Impressionism.

Figure 1: Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872. Oil on canvas, 48 cm * 63 cm, Paris: Musèe Marmottan Monet.

Previous researchers have already done a lot of research and written books on this Impressionist master. For example, Monet or the Triumph of Impressionism, by Daniel Wildenstein, is about Monet’s life with accurate details and many illustrations [2]; Claude & Camille: A Novel of Monet, by Stephanie Cowell, is a novel about the love story between Monet and his wife Camille [3]. Claude Monet: A Biography, by Jason Thompson, is, obviously, a biographic book about Monet [4]. However, so far there is still no study to analyze, objectively, the relationship between Monet and Camille and the changes in this relationship as time passed, from the perspective of Monet’s paintings.

Starting from Monet’s paintings for the first time, this paper analyzes dozens of Monet’s representative paintings related to Camille and depicts the love story of the two based on literature, books and letters and the paintings. Studying the relationship between Monet and Camille is important to the whole history of art, not only because he was a great Impressionist master, but also because it made his paintings full of shine, warmth and love. Through this study, people can learn more about the artist Monet, his life a hundred years ago, and the stories behind his paintings.

The whole paper logically analyzes the relationship between Monet and his wife Camille through paintings. It is divided into three sections according to the time sequence of painting creation. The first section starts from Monet’s acquaintance with Camille to the time when they moved to Argenteuil in 1871; The second section begins with the time they moved to Argenteuil and ends with Camille’s death; The third section describes Monet’s emotional changes after Camille’s death.

2. First Period (1865-1871): From First Met to Argenteuil

As mentioned above, Claude Oscar Monet was born in Paris in the winter of 1840 [5]. When he was five, the family moved to Le Havre, a port city in northwestern France [6]. He developed his enthusiasm and love of art at an early age, and then became known for his caricature portraits (Figure 2) in Le Havre [7].

Figure 2: Claude Monet, Caricature of Eugène Marcel, 1855-1856. Graphite with white chalk on gray wove paper, 23.9 cm * 13.6 cm, Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago.

However, he really began his painting career in 1858 after meeting Eugène Boudin, who recognized his talent, introduced him to landscape paintings, and recommended him to study at Acadèmie Suisse. “Come on, Claude -- your caricatures are fun, but it’s not real art, I mean art; I mean painting, Claude, painting!” Boudin said to Monet [8].

From then on, Monet was on his painting journey. At Acadèmie Suisse, he met Camille Pissarro and the future prime minister of France, Georges Clemenceau, and continued training his skills in landscape painting [9]. After that, he briefly served in the army for a year, then went to Charles Gleyre’s workshop to continue his work with the future Impressionist Alfred Sisley, Frèdèric Bazille, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir [6]. As his skills improved, in 1865, two of his paintings which painted the waterscape of Seine (Figure 3-4) were accepted by the salon -- an annual art event in Paris [10]. The two paintings were well received, which encouraged Monet’s confidence.

Figure 3 (left): Claude Monet, The Seine Estuary at Honfleur, 1865. Oil on canvas, 89.5 cm * 150.5 cm, Pasadena: Norton Simon Museum.

Figure 4 (right): Claude Monet, The Headland of the Heve at Low Tide, 1865. Oil on canvas, 90 cm * 150 cm, Fort Worth: Kimbell Art Museum.

Not long ago, Édouard Manet created The Luncheon on the Grass (Figure 5), but it was rejected by the salon because of its “obscene” content and caused controversy [11]. Monet, who wanted to make a name for himself, saw an opportunity, discarded the dross and selected the essence, drew a painting of his own (Figure 6-7) from Manet’s subject and decided to send it to the salon. It was this painting that introduced him to Camille Doucieux, his future wife.

Figure 5 (left): Édouard Manet, The Luncheon on the Grass, 1863. Oil on canvas, 208 cm * 264.5 cm, Paris: Musèe d’Orsay.

Figure 6 (center): Claude Monet, Lunch on the Grass (left panel), 1865. Oil on canvas, 248 cm * 217 cm, Paris: Musèe d’Orsay.

Figure 7 (right): Claude Monet, Lunch on the Grass (central panel), 1865. Oil on canvas, 217 cm * 248 cm, Paris: Musèe d’Orsay.

Camille has begun work as a model for painters in her teens [12]. She met Monet through the work of Lunch on the Grass and soon fell in love with him. In this painting, Monet painted Camille as the woman in a white dress carrying a plate in the central panel. This painting gives us a glimpse of the impression Monet had on Camille when they first met -- quiet, demure and gentle.

Unfortunately, due to Monet’s mismanagement of time and the size of Lunch on the Grass, the painting never made it to the salon. So Monet asked Camille to model again and created another painting Woman in a Green Dress (Figure 8). This painting was highly praised by the salon for its unique and delicate light and shade on the silk green dress [13]. At the same time, he became acquainted with Camille, as reflected in the painting Camille with a Small Dog (Figure 9) he did privately for Camille.

Figure 8 (left): Claude Monet, Woman in a Green Dress, 1866. Oil on canvas, 228 cm * 149 cm, Bremen: The Kunsthalle Bremen.

Figure 9 (right): Claude Monet, Camille with a Small Dog, 1866. Oil on canvas, 73 cm * 54 cm, Zurich: Foundation E.G. Bührle Collection.

Monet and Camille soon fell in love. Despite the two being still unmarried and Monet’s family objecting to their relationship, Camille was pregnant [14]. Thanks to the rapid development of the railway line, Monet was able to return to Le Havre from Paris, stayed at home in Le Havre and painted the paintings that his familiy brought from him (Figure 10). In August 8, 1867, Camille gave birth to Monet’s eldest son, Jean Monet. Monet’s Jean Monet in the Cradle (Figure 11) shows the scene of his wife taking care of their newborn son.

Figure 10 (left): Claude Monet, Garden at Sainte-Adresse, 1867. Oil on canvas, 98.1 cm * 129.9 cm, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 11 (right): Claude Monet, Jean Monet in the Craddle, 1867. Oil on canvas, 50.8 cm * 37.5 cm.

The baby in the painting is lying quietly in a white cradle, holding a small rattle-drum and smiling curiously at his mother, Camille, who looks at him tenderly. Unlike Monet’s other paintings, which are designed to accurately record light and shadow, this one is warm and full of love, reflected in both its tone and subject matter. It also marked the beginning of the happiest time between Monet and Camille. It doesn’t matter about shadow, brushwork, and salon’s aesthetic. All we can feel in it is love, love for his son, love for his wife. Love is one of the biggest themes in Monet’s paintings and a prequel to his missing of his wife and relatives in his later years.

Monet loved his wife and children deeply. They finally married in 1870 and spent the whole summer at the beach of Trouville, where Monet painted many paintings for Jean (Figure 12), Camille (Figure 13-14) and their poor but happy life (Figure 15) [14]. Their steady life continued until the Franco-Prussian War broke out [15]. Monet took refuge in London alone. During his time in London, he got to know John Constable and Turner, acquainted with Paul Durand-Ruel, who later became the biggest proponent of Impressionism [16].

Figure 12 (L1): Claude Monet, Portrait of Jean Monet Wearing a Hat with a Pompom, 1869. Oil on canvas, Toulouse: The Bemberg Foundation.

Figure 13 (L2): Claude Monet, Camille on the Beach at Trouville, 1870. Oil on canvas, 38.1 cm * 46.4 cm, New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery.

Figure 14 (R2): Claude Monet, The Red Cape (Madame Monet), 1870. Oil on canvas, 99 cm * 79.8 cm, Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art.

Figure 15 (R1): Claude Monet, The Dinner, 1869. Oil on canvas, 50.5 cm * 65.5 cm, Zürich: E.G. Bührle Foundation.

In 1871, after Paris Commune ended, Monet returned to Paris from London [17]. Monet finally had an income by selling paintings to Durand-Ruel; Meanwhile, Monet’s father died in early 1871 and left him a legacy. Monet and his family were suddenly freed from poverty and moved to Argenteuil [14].

3. Second Period (1871-1879): Sweet Years and Grievous Years

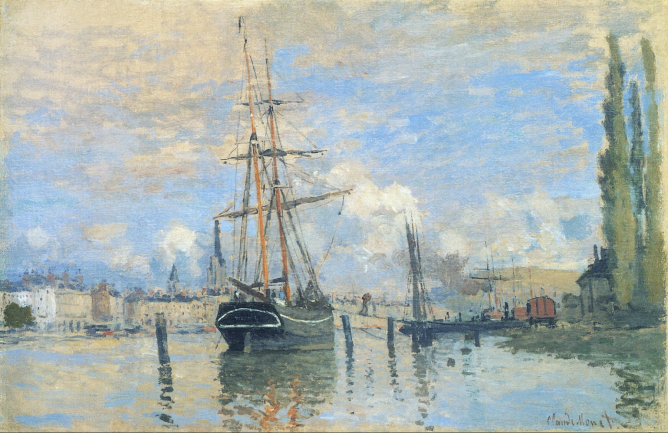

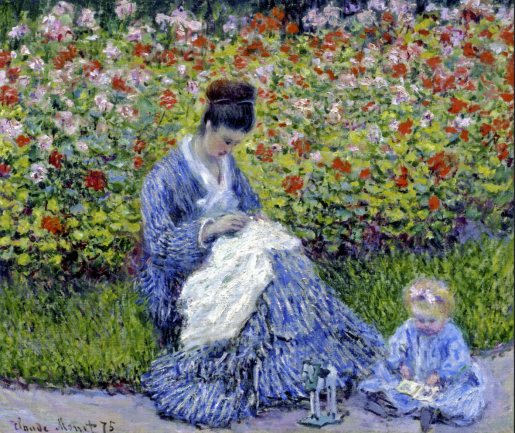

Monet’s family rented a large house with a garden near the Seine River in Argenteuil and lived a very rich and happy life [14]. This comfortable life, where he did not have to worry about livelihood, strengthened Monet’s relationship with Camille, and also dulled some of Monet’s ambitions. He concentrated on painting landscapes (Figure 16-17); on the beautiful, rich life of his family (Figure 18-19); And on his wife whom he had painted so many times (Figure 20-21). It is worth mentioning that none of these paintings were traditional styles that would have pleased the Salon. By that time, Monet had already developed his own style (although the term “Impressionism” hadn’t been invented), namely the painterly brushstrokes, precise capture of light and shade, and colorful depictions [18]. Monet’s paintings at Argenteuil, especially those depicting water scenes of the Seine, laid the foundation for his sensational work Impression, Sunrise (Figure 22) in 1872.

Figure 16 (left): Claude Monet, The Seine at Rouen, 1872. Oil on canvas, 54 cm * 66 cm, Saint Petersburg: Hermitage Museum.

Figure 17 (right): Claude Monet, Autumn Effect at Argenteuil, 1873. Oil on canvas, 55 cm * 74.5 cm, London: Courtauld Institute of Art.

Figure 18 (L1): Claude Monet, A Corner of the Apartment, 1875. Oil on canvas, 81.5 cm * 60.5 cm, Paris: Musèe d’Orsay.

Figure 19 (L2): Claude Monet, Camille Monet and a Child in the Artist’s Garden in Argenteuil, 1875. Oil on canvas, 55.3 cm * 64.7 cm, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

Figure 20 (R2): Claude Monet, Camille Monet on a Garden Bench, 1873. Oil on canvas, 61 cm * 80 cm, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 21 (R1): Claude Monet, Camille Monet at the Window, Argenteuil, 1873. Oil on canvas, 60.3 cm * 49.8 cm, Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Figure 22: Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872. Oil on canvas, 48 cm * 63 cm, Paris: Musèe Marmottan Monet.

In 1874, Monet, along with Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and other painters of a similar style, organized an exhibition in Paris called the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers, which exhibited many artworks including Impression, Sunrise [19]. The exhibition created a furor in Paris, with the critic Louis Leroy commenting that “all the paintings were just ‘impressions’”, and jokingly named their style as “Impressionism” [20]. It was for this reason that Impressionism finally got its name.

The longer the two lived together, the more intense their affection became. Over the next year, as winter turned to spring, Monet painted Camille endlessly: as she embroidered (Figure 23), as she sat in the grass (Figure 24), as she wore a Japanese kimono (Figure 25), as she promenaded with a parasol (Figure 26). His paintings for Camille during this period all reflected the deep love between them, of which The Promenade, Woman with a Parasol (Figure 26) is the most typical. This painting depicts his wife Camille and his son Jean promenading in the meadow. The color of the azure sky and the tender green meadow are reflected in Camille’s long white dress. She and Jean are standing on a hill, the wind breeze gently, the clouds flow slowly, grass grow lively.

Figure 23 (L1): Claude Monet, Madame Monet Embroidering, 1875. Oil on canvas, 65 cm * 55 cm, Philadelphia: Barnes Foundation.

Figure 24 (L2): Claude Monet, In the Meadow, 1876. Oil on canvas.

Figure 25 (R2): Claude Monet, Japan’s (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume), 1876. Oil on canvas, 231.8 cm * 142.3 cm, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

Figure 26 (R1): Claude Monet, The Promenade, Woman with a Parasol, 1875. Oil on canvas, 100 cm * 81 cm, Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art.

Unfortunately, this was the end of their sweet years together. The economic downturn in France meant that Durand-Ruel had no money left to buy Monet’s paintings, and Ernest Hoschedè, who had met Monet in 1875 and provided him with financial support, had gone bankrupt in 1777 [14]. As a result, Monet returned to a life of poverty. At the same time, Camille was suffering from metastatic cervical cancer and was pregnant with her second child with Monet [21].

Due to financial constraints, Monet and his family moved from Argenteuil to Vètheuil with Hoschedè’s family [14]. Some of the letters Monet wrote reflect his desperation at the time. In March 30, 1878, he wrote, “My wife just had another baby and I am unable to pay for medical care that mother and child must have.” [22]. In March 10, 1879, he wrote, “For a month I have been unable to paint because I lack the colours. That’s not important. Right now it’s my wife’s life in jeopardy that terrifies me. It is unbearable to see her suffer.” [22]. Monet’s paintings reflected their life in Vètheuil (Figure 27-29). In Vètheuil, Camille gave birth to her and Monet’s second son, Michel Monet, on March 17, 1878, but her health condition deteriorated, and died at her home in Vètheuil on September 5th of the year after she gave birth to Michel [21].

Figure 27 (left): Claude Monet, Park Monceau, 1878. Oil on canvas, 72.7 cm * 54.3 cm, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 28 (center): Claude Monet, Portrait of Germaine Hoschedè with a Doll, 1876-1877. Oil on canvas.

Figure 29 (right): Claude Monet, The Garden, Hollyhocks, 1877. Oil on canvas, 73 cm * 54 cm, private collection.

Camille Monet on her Deathbed (Figure 30) is Monet’s last painting for Camille, depicting her death on her deathbed. The dead Camille laid lifelessly on her deathbed with her eyes closed, the bedding wrapped around her just like cold, messy feathers. The entire painting is in blue and purple tones, frozen, still and grieved, just like Monet’s emotions when he painted it, which depicts not only Monet’s wife but also Monet’s heart.

Figure 30: Claude Monet, Camille Monet on Her Deathbed, 1879. Oil on canvas, 90 cm * 68 cm, Paris: Musèe d’Orsay.

Monet left more than two thousand paintings during his lifetime, except for this one, which has a small heart behind his signature - a testament to his undying love for Camille. After her death, Monet asked a friend to retrieve the medal - the only souvenir Camille had saved - he had pawned at Montpellier, and hung it around Camille’s neck and accompanied her forever.

4. Third Period (1879-1926): Long Missing at Giverny

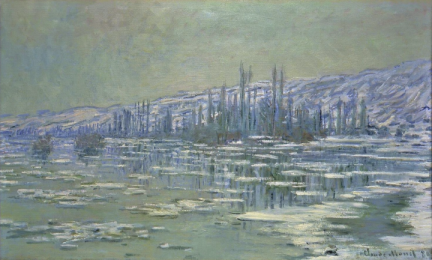

Because of his wife’s death and his lack of income, Monet was devastated for a long time after Camille’s death and lived a depressed life for several years, which is reflected in his paintings. 1875, when Camille was still alive, Monet’s snowy scene paintings (Figure 31) were warm, bright, and joyful; However, in 1880, his snowy scenes (Figure 32) became dilapidated, dead, and hopeless. He tried to relieve his depressed mood by painting. He painted the Seine in winter (Figure 33), the snowy landscape (Figure 34), the road in front of the town (Figure 35), the cliffs (Figure 36) and the sea in his hometown (Figure 37), but all these scenes were extremely lonely.

Figure 31 (left): Claude Monet, Frost, 1875. Oil on canvas, 50 cm * 61 cm, Postdam: Museum Barberini.

Figure 32 (right): Claude Monet, The Frost, 1880. Oil on canvas.

Figure 33 (left): Claude Monet, Ice Floes on Seine, 1880. Oil on canvas.

Figure 34 (right): Claude Monet, Frost near Vètheuil, 1880. Oil on canvas, 61 cm * 100 cm, Paris: Musèe d’Orsay.

Figure 35 (left): Claude Monet, The Road to Vètheuil, Snow Effect, 1879. Oil on canvas, 61.3 cm * 81.6 cm, private collection.

Figure 36 (center): Claude Monet, Calm Weather, Fecamp, 1881. Oil on canvas, 59.7 cm * 73.7 cm, Philadelphia: Matted Museum.

Figure 37 (right): Claude Monet, The Thaw at Vètheuil, 1881. Oil on canvas, 60 cm * 100 cm, Madrid: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza.

Monet finally got better. The ‘worn-out armor’ was restored to a ‘new military uniform’, allowing the lonely painter to face up to his unfortunate life. In 1882, the bottomed-out economy slowly rebounded, the previously bankrupt Durand-Ruel’s business got better [23]. Thanks to Durand-Ruel’s financial support, Monet’s life slowly improved. Colorful colors reappeared in Monet’s paintings, just as they had in Path at Le Cavee, Pourville (Figure 36) and View from the Cliff at Pourville, Bright Weather (Figure 37).

Figure 36 (left): Claude Monet, Path at Le Cavee, Pourville, 1882. Oil on canvas, 105.4 cm * 142.8 cm, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

Figure 37 (right): Claude Monet, View from the Cliff at Pourville, Bright Weather, 1882. Oil on canvas.

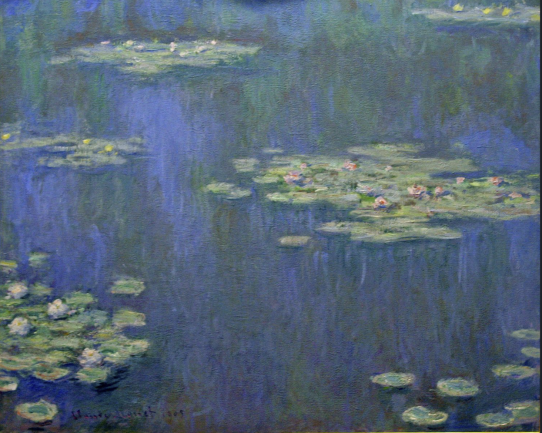

Monet hardly painted any more figures after Camille died; he truly became a landscape painter. He began to create series paintings intentionally, such as the Rouen Cathedral series (Figure 38), the Haystacks series (Figure 39) and the Water Lilies series (Figure 40). The only exception was another two Woman with a Parasol (Figure 41-42), painted for Hoschedè’s eldest daughter, later his daughter-in-law, in which the girl stands quietly on a hillside with a parasol, just as his wife Camille had done eleven years earlier.

Figure 38 (left): Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral, 1892-1893. Oil on canvas, 107 cm * 73.5 cm, Paris: Musèe d’Orsay.

Figure 39 (center): Claude Monet, Haystacks, 1890. Oil on canvas, 73 cm * 92.5 cm, Paris: Musèe d’Orsay.

Figure 40 (right): Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1905. Oil on canvas, 82 cm * 101 cm, Cardiff: National Museums & Galleries of Wales.

Figure 41 (left): Claude Monet, Woman with a Parasol (Study of a Figure Outdoors, Facing Left), 1886. Oil on canvas, 131 cm * 88 cm, Paris: Musée d’Orsay.

Figure 42 (right): Claude Monet, Woman with a Parasol, Facing Right (Study of a Figure Outdoors, Facing Right), 1886. Oil on canvas, 131 cm * 88 cm, Paris: Musée d’Orsay.

Both Monet and Hoschedè have grown old, their children have grown up. Only Camille is left in time, in Monet’s heart.

In 1883, Monet rented the house in Giverny [14]. Seven years later, he saved enough money to buy Giverny and spent the rest of his life there.

5. Conclusion

Overall, Monet and Camille’s relationship, which lasted for 14 years, was loyal, deep, and undying. Although Camille died young and Monet married Alice (the wife of Hoschedè who died in 1891) in 1892, Monet’s longing for Camille persisted -- as can be seen in his paintings. Future scholars could begin by studying Monet’s relationship with Camille in a specific painting or by comparing two paintings, or to study other aspects of Monet, such as his correspondence with his family, his series paintings, or his financial situation.

References

[1]. Auricchio, L. (2004). Claude Monet (1840-1926). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cmon/hd_cmon.htm%20(October%202004).

[2]. Wildenstein, D. (2010). Monet or the Triumph of Impressionism. TASCHEN GmbH.

[3]. Cowell S. (2011). Claude & Camille: A Novel of Monet. Crown.

[4]. Thompson J. (2016). Claude Monet: A Biography. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

[5]. Artincontext. (2022). Claude Monet - The Life and Impressionist Paintings of Monet the Artist. Retrieved from https://artincontext.org/claude-monet/.

[6]. Stace, C. L. (2022). Claude Monet: Life and Art of the Founder of Impressionism. Retrieved from https://magazine.artland.com/claude-monet-bio-paintings-impressionism/.

[7]. Edwards, H. (1943). The Caricatures of Claude Monet. Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951), 37(5), 71-72.

[8]. Strickland M. Features: Eugène Boudin, Monet’s Mentor. Retrieved from https://portraitsocietyofatlanta.org/features-eugene-boudin-monets-mentor/#:~:text=Even%20at%20a%20young%20age%2C%20Monet%20became%20well,talent%20and%20encouraged%20him%20to%20begin%20painting%20landscapes.

[9]. Stephens, H. G. (1904). Camille Pissarro, Impressionist. Brush and Pencil, 13(6), 411-435.

[10]. (2021) Claude Monet, An Impression of His Paintings at the Salon. Retrieved from https://www.impressionism.nl/monet-salon/.

[11]. GalleryIntell. The Luncheon on the Grass by Edouard Manet. Retrieved from https://galleryintell.com/artex/luncheon-on-the-grass-edouard-manet/.

[12]. Hagen R. (1998). What Great Paintings Say. TASCHEN. p. 391.

[13]. Bremen, K. (2022). Woman in a Green Dress by Monet. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/image/15613/woman-in-a-green-dress-by-monet/.

[14]. Cauderlier, A. (2006). Monet and Camille: A Relationship Biography. Retrieved from http://www.intermonet.com/exhibit/bremen/biography.html.

[15]. de B. WEBB, C. (1966). The Origins of the Franco-Prussian War: A Re-Interpretation. Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, 27, 9-20.

[16]. Takac, B. (2021). Paul Durand-Ruel, an Art Dealer Who Launched Impressionists. Retrieved from https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/paul-durand-ruel-art-dealer.

[17]. Bernstein, S. (1941). The Paris Commune. Science & Society, 5(2), 117-147.

[18]. (2022). Characteristics of Claude Monet’s Paintings. Retrieved from https://alianzahipotecaria.com/characteristics-of-claude-monets-paintings/.

[19]. Samu, M. (2004). Impressionism: Art and Modernity. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/imml/hd_imml.htm#:~:text=In%201874%2C%20a%20group%20of%20artists%20called%20the,Monet%2C%20Edgar%20Degas%2C%20and%20Camille%20Pissarro%2C%20among%20others.

[20]. Leroy, L. (1874). Exhibition of the Impressionists.

[21]. Harris, J. C. (2003). Camille on Her Deathbed. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 60(1). 13. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.13.

[22]. (2017). Claude Monet’s Life Through His Letters and Paintings. Retrieved from https://www.maturetimes.co.uk/claude-monets-life-letters-paintings-showing-21st-february/.

[23]. White, E. (2007). The Crash of 1882 and the Bailout of the Paris Bourse. Cliometrica, Journal of Historical Economics and Econometric History, 1, 115-144. 10.1007/s11698-007-0008-2.

Cite this article

Bai,Y. (2023). Monet’s Memory of Camille: A Theme-Based Analysis of Monet’s Paintings. Communications in Humanities Research,3,379-389.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies (ICIHCS 2022), Part 1

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Auricchio, L. (2004). Claude Monet (1840-1926). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cmon/hd_cmon.htm%20(October%202004).

[2]. Wildenstein, D. (2010). Monet or the Triumph of Impressionism. TASCHEN GmbH.

[3]. Cowell S. (2011). Claude & Camille: A Novel of Monet. Crown.

[4]. Thompson J. (2016). Claude Monet: A Biography. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

[5]. Artincontext. (2022). Claude Monet - The Life and Impressionist Paintings of Monet the Artist. Retrieved from https://artincontext.org/claude-monet/.

[6]. Stace, C. L. (2022). Claude Monet: Life and Art of the Founder of Impressionism. Retrieved from https://magazine.artland.com/claude-monet-bio-paintings-impressionism/.

[7]. Edwards, H. (1943). The Caricatures of Claude Monet. Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951), 37(5), 71-72.

[8]. Strickland M. Features: Eugène Boudin, Monet’s Mentor. Retrieved from https://portraitsocietyofatlanta.org/features-eugene-boudin-monets-mentor/#:~:text=Even%20at%20a%20young%20age%2C%20Monet%20became%20well,talent%20and%20encouraged%20him%20to%20begin%20painting%20landscapes.

[9]. Stephens, H. G. (1904). Camille Pissarro, Impressionist. Brush and Pencil, 13(6), 411-435.

[10]. (2021) Claude Monet, An Impression of His Paintings at the Salon. Retrieved from https://www.impressionism.nl/monet-salon/.

[11]. GalleryIntell. The Luncheon on the Grass by Edouard Manet. Retrieved from https://galleryintell.com/artex/luncheon-on-the-grass-edouard-manet/.

[12]. Hagen R. (1998). What Great Paintings Say. TASCHEN. p. 391.

[13]. Bremen, K. (2022). Woman in a Green Dress by Monet. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/image/15613/woman-in-a-green-dress-by-monet/.

[14]. Cauderlier, A. (2006). Monet and Camille: A Relationship Biography. Retrieved from http://www.intermonet.com/exhibit/bremen/biography.html.

[15]. de B. WEBB, C. (1966). The Origins of the Franco-Prussian War: A Re-Interpretation. Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, 27, 9-20.

[16]. Takac, B. (2021). Paul Durand-Ruel, an Art Dealer Who Launched Impressionists. Retrieved from https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/paul-durand-ruel-art-dealer.

[17]. Bernstein, S. (1941). The Paris Commune. Science & Society, 5(2), 117-147.

[18]. (2022). Characteristics of Claude Monet’s Paintings. Retrieved from https://alianzahipotecaria.com/characteristics-of-claude-monets-paintings/.

[19]. Samu, M. (2004). Impressionism: Art and Modernity. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/imml/hd_imml.htm#:~:text=In%201874%2C%20a%20group%20of%20artists%20called%20the,Monet%2C%20Edgar%20Degas%2C%20and%20Camille%20Pissarro%2C%20among%20others.

[20]. Leroy, L. (1874). Exhibition of the Impressionists.

[21]. Harris, J. C. (2003). Camille on Her Deathbed. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 60(1). 13. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.13.

[22]. (2017). Claude Monet’s Life Through His Letters and Paintings. Retrieved from https://www.maturetimes.co.uk/claude-monets-life-letters-paintings-showing-21st-february/.

[23]. White, E. (2007). The Crash of 1882 and the Bailout of the Paris Bourse. Cliometrica, Journal of Historical Economics and Econometric History, 1, 115-144. 10.1007/s11698-007-0008-2.