1. Introduction

The integration of anthropology and psychology with art is an innovation since modern times. Through a "bottom-up" approach, art has been interpreted in a completely different way, making them perfectly applicable to ordinary people.Gestalt psychology aesthetics has been the most recognized method for studying aesthetics through psychological approaches over the past century. It posits that people possess an inherent ability to appreciate art, a process grounded in visual perception theory that creates a "field effect" between the artwork and the viewer, leading to an emotional experience of "heterogeneous isomorphism." This approach emphasizes the "structure" and "organization" of perception and advocates for incorporating cognitive science research into aesthetic studies from a psychological perspective. Current research in this field primarily focuses on theories and experiments related to vision, often critiquing, comparing, or expanding upon the aesthetic theories proposed by various Gestalt psychologists [1]. Aesthetic research goes beyond using scientific theories to explain and test emotions or analyze psychological phenomena. Gestalt theory can be applied to everyday aesthetic activities, making its abstract concepts more accessible and universal. Many people feel uncertain and lack confidence when interpreting or commenting on art, often fearing criticism for their opinions[2]. However, art originates from and enriches life, and everyone should feel empowered to express their views on it. Gestalt psychology aesthetics can serve as a foundational tool for this purpose. This article employs theoretical analysis and case studies to explore the role of Gestalt psychology in art analysis and its influence on ordinary people's appreciation and understanding of art, with a focus on the impact of aesthetic anthropology.

2. Reviewing and Understanding the Application of Gestalt Psychology in Art Appreciation

2.1. Definition of Gestalt Psychology

Several major theories of Gestalt psychology align perfectly with the perception process of artworks. According to Arnheim's theory of visual perception, perception begins with universality, focusing on capturing the most prominent features of objects, which shapes our cognition of what we perceive. This interaction between the subject (viewer) and object (artwork) within this psychological framework is known as the "gestalt" result, emphasizing the viewer's active participation and subjective interpretation. The "field effect" in perception suggests that human perception creates a "perceptual force field" encompassing both physiological reactions and psychological factors. When an object disrupts the balance of the nervous system, it triggers a physiological reaction, forming a "basic structural pattern of force." When this pattern reaches equilibrium, it produces a sense of beauty. Thus, the gestalt function of both the artwork and the appreciator is to achieve "heterogeneous isomorphism," creating an emotional appeal that reflects the interaction between external objective elements and the viewer's inner characteristics [3].

2.2. The Operational Model of Gestalt Psychology in Art Appreciation

Figure 1: Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss

This section will further illustrate these principles using Antonio Canova’s sculpture “Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss” as an example. When viewers observe this piece, they immediately notice the intertwined figures, focused expressions, and entwined arms. While each viewer may focus on different aspects, everyone can perceive the overall emotion conveyed by the work and feel the beautiful love between the two characters. Typically, the general audience remains at this surface level of perception, but an analysis based on Gestalt theory can offer a deeper understanding of the artwork[4].

Shape is the most intuitive visual recognition method for viewers, determined by the overall visual experience. Although "Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss" is not presented in simple geometric shapes, viewers can still naturally extract the corresponding shapes and contours through simplified visual processing. For example, in the sculpture, Cupid's arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and legs are obscured by Psyche, and Psyche's chest is obscured by Cupid's arms. This overlapping visual arrangement expresses a more intimate relationship between the two figures[2]. Furthermore, the outer lines of the sculpture form a stable and balanced X-shaped composition, while the inner lines, determined by the body movements, convey a smooth and soft feeling. These lines do not create a sense of flatness like two-dimensional works; however, their visual unity is governed by the Gestalt law of simplification, integrating the various parts into an organic whole.

In addition, mastering space in sculpture is more challenging than in two-dimensional art. The spatial sense of "Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss" is substantial, with raised and sunken parts interacting to give a sense of depth and dynamics between the two figures. This mastery of space not only highlights the texture and form of the figures but also enhances the sculpture's realism and tactile quality. Moreover, Gestalt psychology emphasizes that visual objects are a structure of forces. The dynamic gestures and tilted lines in "Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss" demonstrate the directionality of force. These visual elements reflect the dynamic and balanced state in the work through the deformation of form and space. Through the postures, body movements, and interactions of Cupid and Psyche, viewers can sense a dynamic state of power and balance.

Lastly, the most profound meaning in a work of art is conveyed directly to the viewer through the perceptual characteristics of its compositional pattern. Even if viewers are unfamiliar with the legend of Psyche and Eros, the sculpture clearly expresses the deep emotions between the two characters. This visual perception relies not on professional artistic knowledge but on humans' innate ability to understand and desire to interpret visual information.

Arnheim argued that: "In great works of art the deepest significance is transmitted to the eye with powerful directness by the perceptual characteristics of the compositional pattern[2]."This can also be understood as an indication that when interpreting a work of art, excessive reliance on conventions or background knowledge can sometimes dilute the artwork's expressive power. Using the analysis of "Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss" as an example, even if viewers are unfamiliar with the story of Psyche and Cupid, they can still easily recognize the deep emotional connection between the lovers depicted. The sculpture conveys a narrative where despite facing challenges, they ultimately find their way to a happy resolution, evoking a profound sense of redemption.This also underscores that ordinary people possess an innate ability to understand art and are naturally inclined to interpret what they see. Therefore, it is crucial to awaken and stimulate this inherent potential. The following exploration aims to demonstrate the practicality of this theory among ordinary individuals.

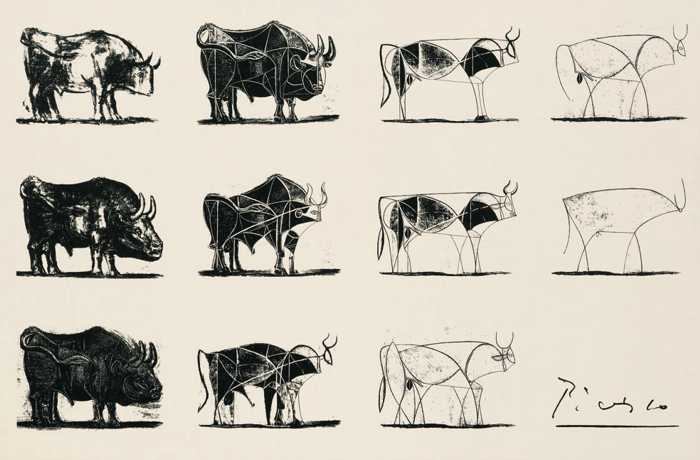

3. Case Study --- Pablo Picasso “Bull”

Gestalt theory encompasses numerous aspects of art appreciation, emphasizing the importance of selecting and applying specific, accessible theories [2]. In this article's case analysis, which combines classic artworks with empirical research—though not statistically significant—it holds significant value for understanding Gestalt theory. This study focuses on the concept of shape within visual perception theory, aiming to explore whether ordinary people can discern the imagery conveyed in artworks through their shapes.

After careful selection, this article chooses Picasso's renowned series "Bull" (consisting of eleven lithographs) as a case study. The objective is to investigate whether ordinary individuals can recognize the depicted image solely through the shapes presented. This choice aligns with the typical application of shape simplification in Gestalt visual perception theory, offering insights into how ordinary people perceive and interpret shape elements within artworks.

3.1. Introduction Pablo Picasso “Bull”

Figure 2: Pablo Picasso “Bull”, 1945 (a series of eleven lithographs)

Picasso's choice of the bull as a recurring motif in his artwork reflects deeper symbolic and artistic intentions. The bull, traditionally seen as a symbol of strength, virility, and cultural identity in Spanish culture, held personal significance for Picasso. During a concentrated period of lithographic activity following World War II, Picasso utilized the bull to explore the transformative power of art. Through a series of 11 prints created over 45 days from a single lithographic stone, Picasso demonstrated his ability to abstract and reinterpret reality[5]. This artistic endeavor not only celebrated the end of the war and the liberation of Paris but also showcased Picasso's innovative approach to blending traditional subject matter with modern artistic techniques.

Great works of art are inherently complex yet meticulously structured, organizing a wealth of meaning into a cohesive whole where every detail finds its defined place and function [2]. This results in paintings characterized by profound orderliness. "Having simplicity" refers to a relative simplicity of shape, requiring harmony between the underlying meaning's structure and the visual pattern it presents, as exemplified by Picasso's paintings. When people use media to replicate something, they exhibit logic and consistency: first, similarity between two perceived and abstracted objects is not based on the equality of their small parts but on the consistency of their essential structural features; second, a sound and healthy mind can instinctively grasp a specific object instantaneously, following the law of linking past experiences with present perceptions—a specific process in forming comprehensive perception by capturing distinctive features [5].

3.2. Practical Exploration and Analysis: Surveying the Appreciation of Famous Works among Ordinary Individuals

In this study, the experimental group was asked to individually identify pictures and write down the intentions depicted in the artwork. Among the ordinary people surveyed, only about 60% successfully identified the image of a "bull" that Picasso intended to express. Other responses included "clothes rack" and "flower-pot shoes." This outcome supports the view of art appreciation in Gestalt psychology. For participants who correctly identified the works, it can be inferred that ordinary people possess a certain level of perception and aesthetic ability. However, for those who had different understandings, this verifies Gestalt psychology’s view that vision is a subjective behavior, emphasizing that viewing is an autonomous and rational ability. This leads to different interpretations based on personal memory and visual information integration. The varied responses, such as "clothes rack" or "flower-pot shoes," are rooted in individual experiences and result from complex integration of perceptual information.

Gestalt psychology posits that "all aesthetic activities start from perception and aim at aesthetic experience" [6], a point this study aims to prove. Although individual perceptual differences lead to diverse interpretations of the same artwork, in this experiment, differences in understanding may extend beyond pure perceptual differences. For instance, while a five-year-old child may have innate perceptual abilities to recognize the image, they would likely struggle to grasp the deeper meaning of "Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss" due to a lack of rich life experience. This highlights the need to find common cognitive points that can be universally applied while considering individual differences. This exploration touches on the impact of individual living environments on experience and cognition, which is understood as "contextual aesthetics" in aesthetic anthropology.

4. Analysis of the influence of aesthetic anthropology

Van Dam, a prominent figure in the emerging field of aesthetic anthropology, views aesthetic activities as a universal human characteristic. He believes that human aesthetics are universal and that aesthetic phenomena are relevant and pervasive in human life. For example, people unconsciously engage in aesthetic activities daily, such as evaluating a person's appearance, the design of clothing, the furnishings of a room, and the layout of an environment.

Van Dam divides human aesthetics into three levels: "evolutionary aesthetics," "contextual aesthetics," and "philosophical aesthetics." "Evolutionary aesthetics" is rooted in the evolution of organisms, particularly the human visual nervous system, positing that "human evolution enables us to perceive the world through the senses, especially through vision" [7]. "Contextual aesthetics" refers to the influence of social and cultural context on aesthetic experience. It is a significant method in anthropological research and the primary basis for applying aesthetic understanding to ordinary people. "Philosophical aesthetics" is considered a reflective existence based on cross-cultural comparative studies, and it is currently controversial in the academic community. It is not particularly relevant to the topic of this article. Given that “evolutionary aesthetics” aligns closely with Gestalt theory and can be effectively replaced and refined by it, this section primarily draws on Van Dam’s experimental conclusions regarding “contextual aesthetics” [7].

As an interdisciplinary subject that bridges anthropology and aesthetics, aesthetic anthropology focuses on "embedded aesthetics" experienced and integrated into the daily lives of people. It is committed to examining aesthetic evaluations and choices people make in their everyday lives. Through extensive and rigorous "field surveys," it demonstrates the universal and particular aesthetic phenomena influenced by social and cultural differences across various nationalities, regions, and cultural circles.

Interestingly, while people are adept at casually evaluating any aesthetic object in their daily lives, they become cautious and hesitant when commenting on artworks in exhibitions. This may stem from the longstanding empirical study of aesthetics, where artists are seen as key sources of information about art and beauty. People tend to entrust the interpretation of art to so-called "professionals," including the artists themselves and experts in related fields, placing high trust in their authority. This trust is based on respect and recognition for the creators and acceptance of the professional knowledge, experience, and judgment of the experts[8].

However, once artworks are publicly presented, the right to interpret them is equally transferred to all viewers. In this process, the creators' intended ideas and the viewers' interpretations can diverge or even contradict each other, as art is inherently subjective and cannot be defined by right or wrong. Aesthetic judgments are not quantifiable. Take Duchamp's "Fountain" as an example. Duchamp's original intention was to liberate art from the conventional definitions of "beauty and ugliness," yet people have continuously copied, spread, and explored its aesthetic value from various perspectives. This does not imply that everyone's understanding is incorrect. Rather, it reflects the diverse exploration on the path of aesthetics, illustrating that everyone can interpret works of art according to their own ideas.

5. Conclusion

This paper finds that integrating anthropology and psychology with art has fundamentally changed how people understand and appreciate art, making it more accessible to ordinary individuals. The application of Gestalt psychology in art appreciation, as demonstrated through Antonio Canova's sculpture "Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss," shows that viewers can perceive and emotionally resonate with the artwork's themes even without extensive artistic knowledge. Similarly, Picasso's "Bull" series illustrates how ordinary people can recognize and interpret shapes in art, supporting the idea that individuals have innate perceptual abilities and aesthetic tastes.

Additionally, this paper explores how social and cultural contexts influence aesthetic experiences from the perspective of aesthetic anthropology, particularly "contextual aesthetics." This field emphasizes that aesthetic activities are embedded in daily life, with people continuously evaluating their surroundings aesthetically. In the process of art appreciation, barriers should be removed to encourage active participation and subjective interpretation by everyone. The concept that anyone can become a "great artist" reflects not just a profession but an attitude and belief. This paper further enriches the understanding and appreciation of art through this open perspective, promoting a more inclusive and dynamic engagement with artistic expression.

However, the study relied on qualitative analysis through subjective interpretations and emotional responses. Future studies could incorporate more quantitative methods, such as surveys with scaled responses or neurological measurements, which could provide more robust data.

References

[1]. Peng, J. X. (2006). Introduction to Art Studies (Chapter 12). Peking University Press.

[2]. Arnheim, R. (1974). Art and Visual Perception (X. Expression, p. 458). University of California Press.

[3]. Yi, Z. T. (2019). Lectures on Aesthetics (Lecture 4). Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House.

[4]. Xing, C.T. (2007). Introduction to World Art (Volume 2) (Chapter 5). Liaohai Publishing House.

[5]. Goldstein, J. L. (2010). How to win a lasker? take a close look at Bathers and Bulls. Nature Medicine, 16(10), 1091-1096.

[6]. Zhao, Y.L. (2023). Muse Returns: Literary Psychology in the New Era (Chapter 2, Section 3). Zhejiang University Press.

[7]. Fan, D. (2022). Aesthetic Anthropology. Culture and Art Publishing House.

[8]. Schellekens, E. (2022). Conceptual art. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2022 Edition).

Cite this article

Wang,X. (2024). Analyzing the Impact of Aesthetic Anthropology on Art Appreciation Through the Lens of Gestalt Psychology. Communications in Humanities Research,39,184-189.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Peng, J. X. (2006). Introduction to Art Studies (Chapter 12). Peking University Press.

[2]. Arnheim, R. (1974). Art and Visual Perception (X. Expression, p. 458). University of California Press.

[3]. Yi, Z. T. (2019). Lectures on Aesthetics (Lecture 4). Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House.

[4]. Xing, C.T. (2007). Introduction to World Art (Volume 2) (Chapter 5). Liaohai Publishing House.

[5]. Goldstein, J. L. (2010). How to win a lasker? take a close look at Bathers and Bulls. Nature Medicine, 16(10), 1091-1096.

[6]. Zhao, Y.L. (2023). Muse Returns: Literary Psychology in the New Era (Chapter 2, Section 3). Zhejiang University Press.

[7]. Fan, D. (2022). Aesthetic Anthropology. Culture and Art Publishing House.

[8]. Schellekens, E. (2022). Conceptual art. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2022 Edition).