1. Introduction

Language loss signifies not merely a loss of a communication tool but also an entire worldview, along with the oral traditions, belief systems, and collective memories embedded within it. According to UNESCO, one language dies every two weeks, and nearly half of the world’s 6,000+ languages are at risk of disappearing by the end of the century. Scholars have long documented the decline of Indigenous languages under the influence of dominant cultures, a process accelerated by state policies, urban migration, mainstream media, and the socioeconomic pressure to assimilate. While assimilation may grant access to material, educational, or occupational opportunities, it often comes at the cost of cultural continuity. Resistance to assimilation takes many forms, from language revitalization movements to the preservation of oral traditions, rituals, and intergenerational knowledge. Within these preservation efforts, the influence of gender roles in shaping how culture and language are passed down has long been acknowledged.

The Hmong American community, which this study focuses on, offers a compelling case study of these dynamics. The Hmong are a kinship-based ethnic group that originated in southern China, primarily in the provinces of Hunan, Guizhou, and Yunnan, and later migrated throughout Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand. Following the Indochinese Wars, particularly the US involvement in the “Secret War” in Laos, tens of thousands of Hmong refugees resettled in the United States between 1975 and 1980, forming a diaspora that now numbers over 330,000 people. Hmong communities also formed in other countries such as France, Australia, Germany, and Canada. In the United States, some Hmong Americans live in close-knit communities, particularly in Minnesota, California, and Wisconsin. Others are more dispersed, facing greater challenges in maintaining cultural ties. Like many displaced communities, Hmong Americans continue to navigate the difficult balance between cultural preservation and assimilation. For example, research by [1] suggests that Hmong elders who strive to uphold traditional beliefs often face challenges navigating a Western healthcare system grounded in the biomedical model, which frequently overlooks or misunderstands Hmong cultural values.

The Hmong language, a tonal language belonging to the Hmong-Mien linguistic subfamily, is traditionally oral and has been used for centuries to pass down cultural knowledge through chants, ritual rites, poems, folktales, and ceremonial songs. Writing systems have historically not been prioritized, and many elders continue to fear that increased literacy in written scripts may further undermine oral tradition. Of the two dozen or so scripts created for the Hmong language, the most widely used today is the Romanized Popular Alphabet (RPA), developed by Christian missionaries in 1953 [2].

Language and cultural preservation is closely tied to gender roles. Traditionally, Hmong society has operated under a patriarchal structure in which men held authority as clan leaders, while women were expected to preserve domestic customs through cleaning, cooking, caregiving, and embroidery. Under the patrilineal clan system, wives and their children become members of the husband’s clan, and all social support and decision-making traditionally come from male elders [3,4]. However, as Hmong Americans adapt to US society, gender roles are shifting. Women are increasingly pursuing higher education and contributing financially to their families, sometimes more than men, as skills such as sewing, caretaking, and garment work translate into economic opportunity [5,6]. Still, many women continue to uphold traditional cultural responsibilities at home, creating a complex tension between modern values and inherited expectations.

Despite a growing body of research on Hmong gender dynamics and identity negotiation, there is limited empirical work that explores how these evolving gender roles affect the transmission of Hmong language and culture. Most studies treat gender roles and cultural loss as separate trajectories, without fully examining their intersection. This study seeks to fill that gap by investigating how Hmong men and women in the US perceive their responsibilities in preserving linguistic and cultural heritage and how those roles may be evolving across generations. By focusing on gender within the broader context of diaspora, assimilation, and cultural preservation, this research aims to contribute to more inclusive and effective strategies for sustaining Hmong identity in an increasingly globalized world.

2. Literature review

Scholars have documented the decline of indigenous languages under the powerful influence of dominant languages, often exacerbated by government policies and the socioeconomic pressure to assimilate into mainstream culture. Balazs Huszka et al. highlight these tensions in their study of Indonesia, where more than 700 regional languages face growing endangerment [7]. Over half are at risk of extinction due to weak institutional support, disrupted intergenerational transmission, and the dominance of the national language. These dynamics reflect a global pattern in which minority communities must continuously negotiate between cultural survival and assimilation within an encroaching mainstream. Around the world, minority groups have implemented innovative strategies to counteract language and cultural erosion. For example, the Māori of New Zealand revived their language through Kōhanga Reo (language nest) preschool programs [8]. Hawaiians saw a resurgence due to immersion schools and official recognition of their language. In Wales, government policies have normalized bilingualism in education, media, and public life [9]. These examples underscore the vital role of institutional support, community engagement, and intergenerational transmission in preserving linguistic heritage. Within the Hmong community, a similar tension between cultural preservation and assimilation into dominant cultures exists.

The Hmong began arriving in the United States in 1975 following their alliance with the CIA during the Vietnam War. Recruited to fight in the “Secret War” in Laos, they were promised resettlement support should the US mission fail [10,11]. After US withdrawal in 1973, thousands of Hmong fled persecution, and the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1976 enabled their resettlement. Today, over 335,000 Hmong Americans live in the United States, primarily in California, Minnesota, and Wisconsin [12].

To understand cultural preservation within this diaspora, it is essential to examine Hmong religion and ritual. Most Hmong traditionally practice Animism, believing that individuals have multiple souls (plig) that maintain spiritual balance [13]. Illness is often attributed to soul loss, prompting healing rituals led by shamans who mediate between physical and spiritual worlds. One common ritual, hu plig, calls the soul back to the body after sickness, shock, or childbirth. Items such as silver neck rings (xauv) are used to “bind” the soul, especially in children and those recovering from illness. In more serious cases, shamans travel to the spirit world to recover the lost plig. Prior to burial, txiv xaiv, a funeral song, is performed to guide the soul to the ancestral world and to comfort the living [14].

The endangerment of the Hmong language is the result of multiple intersecting factors, including war, forced migration, and assimilation into dominant culture [15,16]. Scholars emphasize that academic success among students of color is closely tied to their understanding of their own linguistic and cultural identities [17]. Yet within the Hmong American community, there is a growing perception that Hmong language and culture are economically uncompetitive and therefore expendable in pursuit of the American Dream [18]. Fluency in English and assimilation into white, mainstream culture are often seen as prerequisites for success, while Hmong language use is increasingly limited to informal or weekend settings [19]. As a result, many Hmong youth no longer speak the language fluently or maintain traditional worldviews, a cultural shift that has occurred within just a few decades of resettlement [20].

Despite these sacrifices, the vast majority of Hmong Americans remain among the most socioeconomically marginalized due to their agricultural background and limited education, with 35% of Hmong children living below the federal poverty line, three times the rate of the general US population [21]. Hmong youth are, in effect, giving up their language, culture, and thousands of years of oral tradition to survive within a capitalist society that prioritizes conformity to dominant norms [22]. This erasure of language comes at a cost: research has linked cultural and linguistic loss to increased rates of depression, substance abuse, and other social challenges [23]. In response, the Hmong American community has launched several efforts to preserve their heritage. Community-driven efforts to preserve Hmong language and culture have taken several forms, including: (1) after-school and weekend programs focused on Hmong language and traditional cultural activities; (2) specialized public charter schools in states like Minnesota, California, and Wisconsin that prioritize Hmong language instruction and cultural heritage in their mission; and (3) heritage language classes and bilingual education tracks offered in public school systems with significant Hmong student populations. These initiatives represent an urgent attempt to reclaim language as a form of resilience and cultural survival in the face of ongoing marginalization [24].

In the span of 40 years in the United States, the majority of Hmong youth no longer espouse traditional Hmong worldviews [25]. Hmong society is historically patrilineal and patriarchal. Clan identity is passed through the father, and decisions are made by male elders [3]. Upon marriage, women and children join the husband’s clan. While these structures continue in diaspora, migration has altered traditional roles. Hmong women, whose domestic skills like sewing and caregiving translate well into wage labor, increasingly support families financially and challenge male dominance [5]. Meanwhile, generational gaps in language fluency and cultural knowledge have widened, with youth slowly acculturating to US norms [26].

This cultural shift is particularly influenced by traditional gender roles. Historically, Hmong society has adhered to a rigid gender hierarchy, positioning men as decision-makers, while women have been tasked with upholding domestic and caregiving responsibilities [27]. However, research by Bao Lo and Kao Lee Yang suggests that this dynamic is shifting [28,29], especially among young Hmong American women who increasingly endorse more egalitarian gender roles. Their findings reveal a growing internal conflict: while younger Hmong women embrace modern values, many still conform outwardly to traditional expectations, particularly in cultural and familial settings. This tension is further complicated by the educational pursuits of second-generation Hmong American women, who often view academic success as a pathway to mainstream integration and a means of challenging traditional gender norms.

A growing body of scholarship has explored how second-generation Hmong American women navigate traditional gender expectations alongside mainstream American ideals. Many Hmong girls equate gender equality with white femininity and associate it with the perceived freedom and success of middle-class American families [30,31]. Therefore, they often pursue higher education not only as a path to economic mobility but also as a means to reject traditional Hmong gender roles, which they view as limiting or outdated. Pyke and Johnson frame this dynamic through the concepts of hegemonic and subordinated femininities, suggesting that racialized hierarchies influence how young Hmong women construct their gender identities [30]. As a result, American notions of gender equality are idealized, while traditional Hmong femininity is often internalized as deficient. Hmong girls model their aspirations after dominant images of American family life, leading them to reframe their own cultural expectations as restrictive [31].

Traditional Hmong gender roles emphasize patriarchy and female submission. Women are expected to domestically support the male head of household, obey elders, and take on caretaking responsibilities from a young age [32,29]. Men are raised to lead clans and represent the family in public life [33], while women perform the domestic and cultural labor that sustains everyday traditions. Yet, as Hmong families resettle in the US, these structures are evolving. Both Hmong men and women are moving away from traditional expectations in favor of more egalitarian roles [29], with education acting as a major driver of this shift. Suh notes that Asian American women broadly experience identity conflict as they navigate contrasting ideals from Eastern and Western cultures. While some embrace modern gender roles and autonomy, others continue to support traditional ideals of male authority [34].

These tensions reflect a broader cultural negotiation in which both Hmong men and women are increasingly navigating the space between cultural preservation and adaptation to mainstream society. While Hmong women have often been at the center of discussions about negotiating traditional expectations and modern aspirations, shifting gender roles are also influencing how men participate in cultural transmission. Men are not only continuing their roles as ritual leaders and clan representatives but are also adapting to new responsibilities in domestic and educational settings. This study builds on previous findings by examining how evolving gender dynamics impact the preservation of Hmong language and cultural practices across generations, with particular attention to the dual pressures of tradition and assimilation.

3. Methods

This study aims to explore gendered practices of maintaining the community language and cultural practices amongst members of the Hmong American community using a mixed-method survey design. This survey includes both quantitative (multiple-choice) and qualitative (short answer) questions, allowing for both statistical and thematic analysis. See Appendix for survey questions.

A total of 32 individuals participated in the study. Participants were Hmong Americans, recruited through community networks, social media platforms, and word-of-mouth. The survey was distributed via Google Forms and completed anonymously to ensure privacy and encourage honest responses.

The questionnaire covers four main areas: (1) demographics, (2) language use and transmission, (3) participation in cultural practices (e.g., embroidery, storytelling, cooking), and (4) perceptions of gender roles in cultural preservation. It also asks participants whether these roles have changed across generations or become more inclusive in diaspora settings.

Data will be analyzed to identify patterns by gender, age group, and cultural involvement. Quantitative responses are automatically visualized through Google Sheets and python, while qualitative responses will be summarized in the results section. The goal is to gain insight into how cultural and linguistic preservation is negotiated within a gendered framework, and how these dynamics are evolving across generations.

4. Results

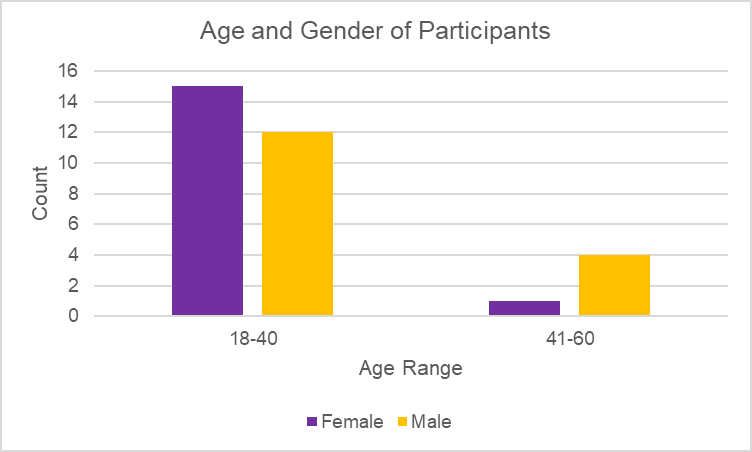

The majority (84%) of participants were between the ages of 18 and 40, including 15 females and 12 males. In the 41–60 age group, there were five participants: one female and four males.

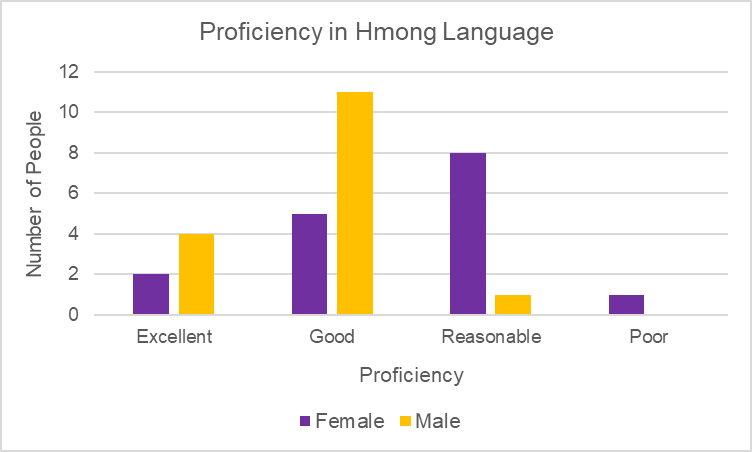

There exists a gendered difference between perceived language abilities, with male participants tending to express greater confidence in their language abilities than female participants. This disparity raises questions about language exposure and usage patterns. It is possible that men receive more Hmong instruction because traditionally men are more valued within Hmong culture as individuals. The lower self-reported fluency among women could also reflect limited usage outside the home, pointing to potential gaps in both access and practice that should be further researched.

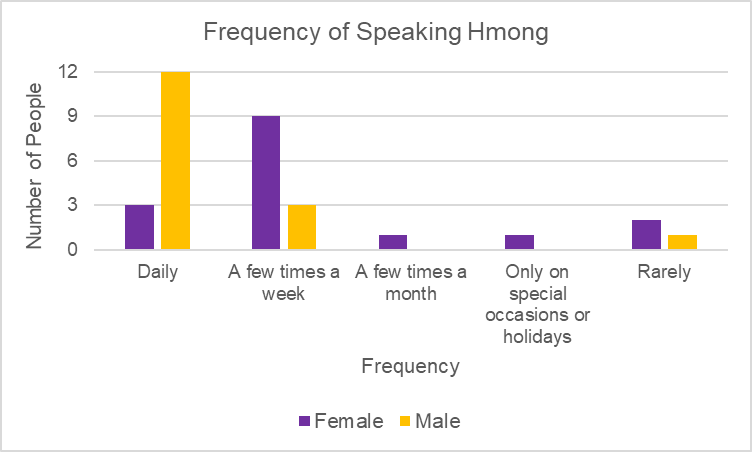

In the highest frequency category, daily usage, 12 men said they use Hmong daily while only 3 women did. This suggests that men are more likely than women to use Hmong regularly in their daily lives, indicating a gender disparity in high-frequency language use. Conversely, women made up the majority in lower-frequency usage categories. One possible explanation is interracial marriage; many women are married to non-Hmong partners and therefore do not speak Hmong regularly within their own households [35]. Instead, they may primarily use the language when interacting with elders or peers.

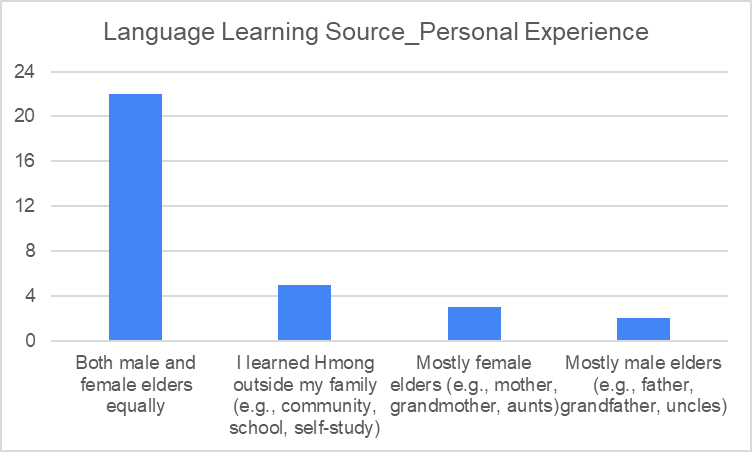

The majority of Hmong American participants reported learning the Hmong language equally from both male and female elders, indicating that cultural and linguistic education is a shared responsibility across genders. In addition to family influence, some respondents also acquired Hmong through community schools or self-study. Notably, three participants said they learned primarily from female elders, while only two reported learning mostly from male elders, further underscoring the prominent role of women in language transmission.

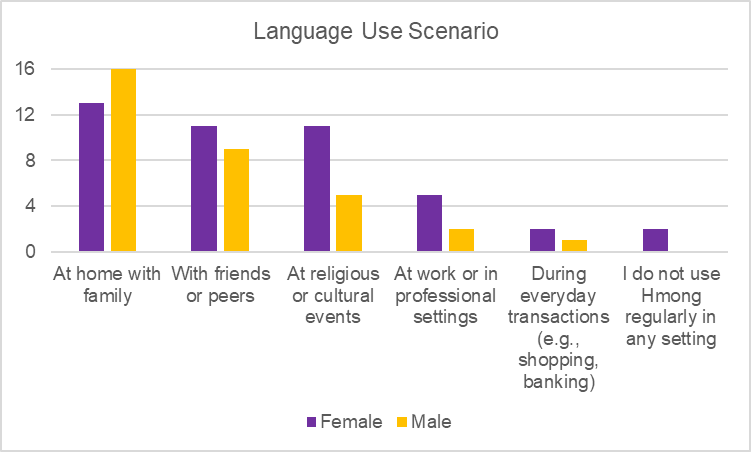

All 16 male respondents reported using Hmong at home with their family, while female participants indicated a broader range of usage settings, including professional and transactional contexts. Interestingly, women reported using Hmong more frequently at religious or cultural events, despite the fact that such rituals have traditionally been male-dominated. This bar chart suggests that women engage with the Hmong language in a more diverse range of contexts than men. Outside the home, they are more likely to use Hmong when interacting with friends, colleagues, or during cultural or religious events. This indicates that, overall, women tend to take a more active role in using the Hmong language for communication across various settings.

Hmong is primarily spoken in intimate, interpersonal settings, typically among close friends and family members. This data suggests that Hmong language acquisition and preservation are largely dependent on proximity and closeness of relations. Hmong is primarily used in personal and family settings, as few individuals report using it in public or professional contexts. This pattern highlights the intimate nature of Hmong language use and suggests that efforts to preserve it may need to focus on strengthening familial and community networks wherein the language naturally thrives.

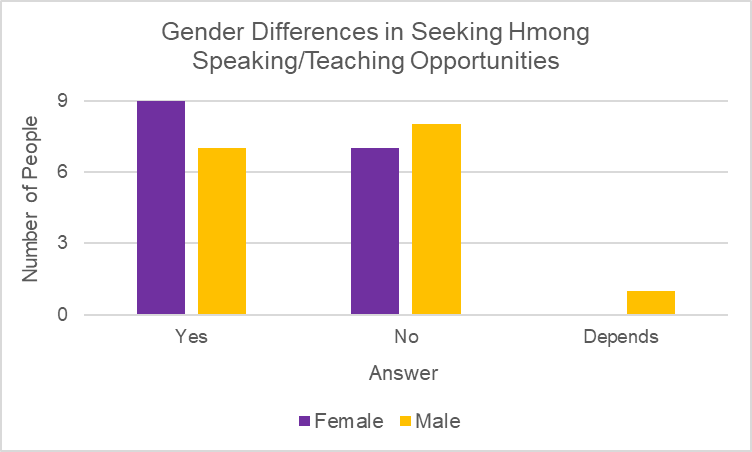

Half of the participants indicated that they would actively seek out opportunities to speak or teach Hmong. This limited initiative may be a key factor contributing to the ongoing decline of the language. In the Hmong American community, there exists a discrepancy between genders regarding efforts to maintain the Hmong language in their communities. Female participants were 12% more likely to report actively engaging in language transmission compared to male participants. Additionally, the unique response regarding music-based teaching came from a female respondent, suggesting that women may more frequently incorporate creative or culturally rooted strategies to preserve the language. When asked about cultural practices, one respondent noted that women often serve as storytellers, using poems and songs to pass down the Hmong language and history. Male respondents, by contrast, were 7% more likely to report not actively teaching or speaking Hmong, and fewer offered nuanced or conditional responses. These findings suggest that while Hmong language maintenance remains inconsistent overall, women may be playing a more active role in cultural and linguistic preservation, reflecting broader patterns of gendered responsibility in intergenerational knowledge transfer within the Hmong American community.

When asked whether they would teach Hmong to their children, all female respondents indicated that they would, demonstrating a strong commitment to intergenerational language transmission among Hmong women. In contrast, one male respondent explicitly stated that he would not teach Hmong to his children. While the sample size is limited, this gendered difference suggests that women may feel a greater sense of responsibility or motivation to preserve the language within the family context.

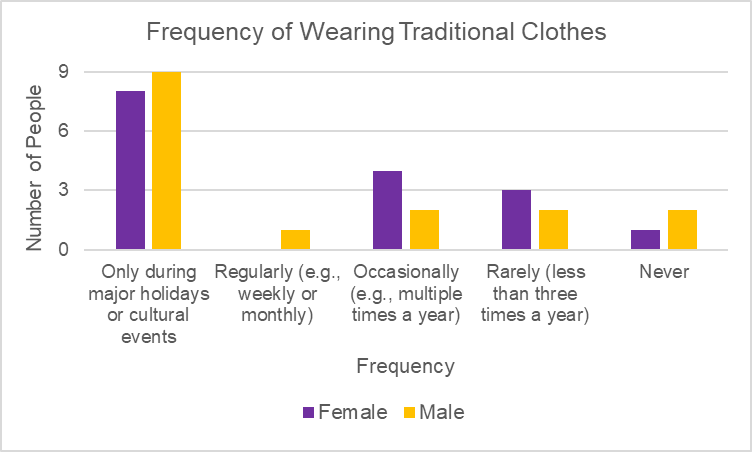

The vast majority of both male and female participants reported wearing traditional Hmong clothing during major cultural events. The data shows nearly identical patterns across genders, indicating no statistically significant difference in this practice. Aside from holidays, several female respondents noted that they also wear traditional Hmong clothing at other times throughout the year, suggesting that women engage with traditional dress in a more varied range of contexts. Overall, participants, regardless of gender, approach the wearing of Hmong attire in similar ways, highlighting it as a shared expression of cultural identity.

The expected practices of a woman and how many people think women are supposed to do these tasks.

The survey also asked participants to list cultural practices and indicate which ones are associated with specific genders.

|

Cultural Practices of Female |

Count of Answers |

|

Cooking |

14 |

|

Caretaking |

8 |

|

Sewing |

6 |

|

Embroidery |

5 |

|

Cleaning |

4 |

|

Farming |

3 |

|

Butcher chickens |

2 |

|

Preparing/wearing Hmong clothes |

2 |

|

Craft Hmong inspired arts |

1 |

|

Gardening |

1 |

|

Teaching children |

1 |

|

Herbal remedies |

1 |

|

Improvised Sung Poetry |

1 |

The most common responses for female cultural practices emphasized domestic labor and caregiving. Cooking was the most frequently cited activity by far, with 14 mentions, followed by caretaking (8), sewing (6), embroidery (5), and cleaning (4). Several respondents also listed tasks related to cultural preservation, including preparing and wearing traditional Hmong clothing, crafting Hmong-inspired art, and passing on herbal remedies. While farming was one of the few overlapping roles shared with male respondents, women’s responsibilities were generally rooted in everyday cultural maintenance and nurturing. Notably, only one respondent cited “teaching children” as a cultural practice, suggesting that despite women’s central role in household and community life, intentional intergenerational transmission may not be explicitly emphasized or widely recognized. One respondent noted that because men often receive more formal education than women, there tends to be a greater expectation for them to educate the next generation. These responses affirm that traditional gender divisions remain influential in shaping how cultural practices are learned and sustained within Hmong American communities. Many female respondents said they learned from their mothers and grandmothers, indicating that women’s skills are passed down from generation to generation. In contrast, men rarely mentioned this; it’s possible they learned from clan leaders, other senior male relatives, or through formal apprenticeship.

|

Cultural Practices of Male |

Count of Answers |

|

Rituals (eg. Shaman, Soul Calling) |

10 |

|

Butcher animals (cow/pig) |

4 |

|

Customs (eg, wedding and funeral) |

4 |

|

Cooking at mass gatherings |

3 |

|

Hunting/Fishing |

3 |

|

Farming |

3 |

|

Clan leadership |

2 |

|

Ancestral Worship |

2 |

|

Acquiring an adult name (npe laus) |

1 |

|

Playing Qeej |

1 |

|

Teaching |

1 |

Survey data on male-associated cultural roles highlights the continued influence of patriarchal traditions in the Hmong community. The most frequently cited practice among male respondents was performing rituals such as shamanism and soul calling, with 10 mentions. Other commonly noted roles included butchering animals (4), managing wedding and funeral customs (4), and cooking at mass gatherings (3). Practices like hunting, farming, and clan leadership were each cited by three or fewer individuals, reflecting both traditional subsistence activities and positions of communal authority. Less frequently mentioned but culturally significant roles included ancestral worship, acquiring an adult name (npe laus), and playing the qeej, a traditional reed instrument. These responses suggest that Hmong men are largely associated with spiritual, ceremonial, and leadership roles, as well as tasks requiring physical labor and symbolic knowledge. This reflects that Hmong culture is a patriarchy because the rituals that are perceived to be important are completed by men.

Embroidery, sewing, caretaking, and cooking were most commonly associated with women, typically taught by mothers, grandmothers, and other female relatives. However, responses varied; some participants affirmed clear gender divisions in cultural practices, while others emphasized increasing flexibility or rejected the existence of gendered roles altogether. One respondent detailed the traditional distinctions:

New Year/Ancestral Worship/ Soul-Calling: Some rituals (like certain shamanic ceremonies) are traditionally male dominated. Women often prepare food and clothing for these events. Embroidery & Sewing: Traditionally a female-dominated skill. Taught by mothers, grandmothers, and older female relatives. Raising children, herbal remedies: Primarily a female responsibility, though men contribute in different ways. Taught by mothers, aunts, and elder women. Cooking Traditional Foods: Mostly women, though men may cook for large gatherings. Taught by mothers and grandmothers.

In contrast, another participant described a more egalitarian upbringing, stating:

“Rituals, funerals, weddings, birthing of newborns—[there’s a] 50/50 on cooking and caretaking. Rituals are usually done with a shaman (can be both female/male). There are no gender roles in my home. Growing up, there were no gender roles as well. During weddings/funerals, there usually are gender roles, with females cooking and prepping food, [while] males are usually doing the butchering and ceremony duties.”

Hmong cultural practices remain deeply gendered, though many participants noted a gradual shift towards more fluid roles within an American context.

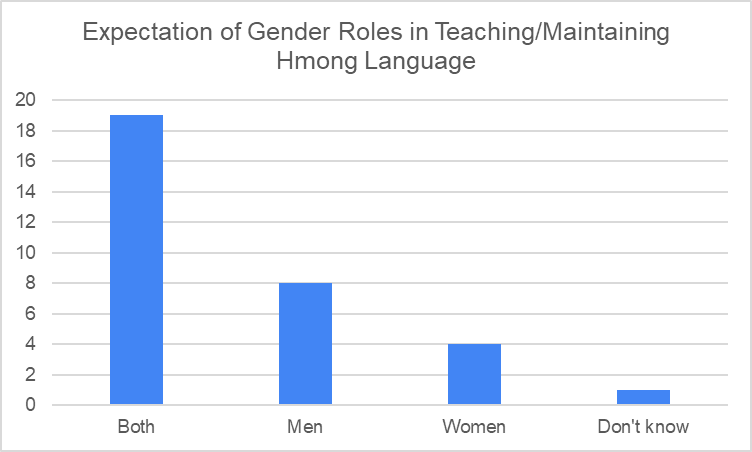

A strong majority of respondents (19 out of 32) indicated that both men and women are expected to play a role in language transmission. This reflects a shift away from traditional, male-dominated structures and suggests an increasingly shared responsibility between genders. However, there were still notable differences: 8 participants believed that there was a greater expectation on men to carry this responsibility, while only 4 selected women, showing that perceptions of male authority in cultural leadership persist. These results point to evolving, yet uneven, beliefs about gendered responsibility in preserving linguistic heritage, potentially influenced by both traditional clan structures and new dynamics in the U.S. diaspora.

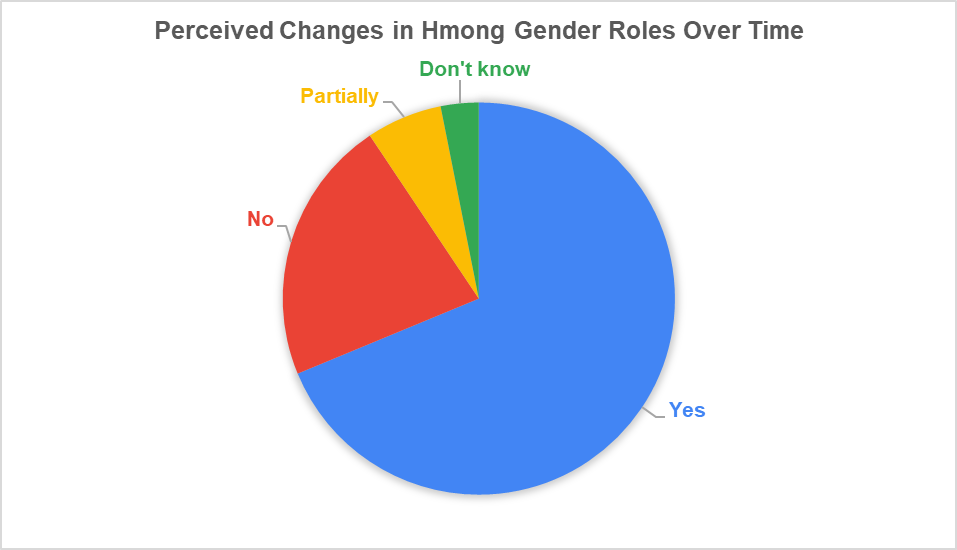

When asked whether gender role expectations around language and cultural transmission have shifted over time, a clear majority of respondents answered yes, identifying significant generational changes. There are several reasons for this: participants noted that many Hmong Americans, especially women, have begun to challenge traditional gender norms and expectations. Interracial marriage and exposure to Western ideals have also played a role, with one respondent commenting that “we’re more Americanized now and not forced to speak Hmong.” Gender expectations are also becoming more neutral because women are standing up for themselves and receiving better education. Responsibilities once traditionally reserved for men, such as educating the next generation, are now increasingly being shared or taken on by women. Others attributed the change to younger Hmong generations being more Americanized and less interested in their culture, with some noting a shift toward more gender-neutral roles. At the same time, a portion of participants believed expectations had remained unchanged, or had only partially shifted. Those who responded with “no” stated that religious customs (such as shamanism, weddings, and funerals) are still male-dominated. Women only participate but are not explicitly taught these skills, indicating that the patrilineal traditions of Hmong society still persist. These findings indicate that while gender roles in cultural preservation are in flux, they continue to reflect a complex interplay of tradition, identity, and adaptation to life in the United States.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal a nuanced and evolving landscape of language use and cultural preservation within the Hmong American community, shaped significantly by gender dynamics. While men reported higher confidence in their language abilities and greater frequency of daily use, women were more likely to express active intentions to speak and teach the language to future generations. This discrepancy suggests a gendered division between performance and transmission: while men may dominate public or ritual use of the Hmong language, women play a central role in sustaining it through interpersonal and familial communication. Despite men often reporting higher fluency, it appears that women contribute more consistently to everyday language preservation.

Language usage patterns further reinforce this divide. All male participants reported using Hmong at home with family, while women showed broader usage in professional and cultural settings. This suggests that women may play a more adaptive role in maintaining language across varied domains, especially as they navigate both traditional expectations and modern social roles. Furthermore, despite the intimate nature of Hmong language use, often confined to family and close community contexts, fewer than half of participants expressed initiative to seek out opportunities for active use or instruction. This lack of engagement is a critical concern for language vitality and may reflect broader trends of assimilation and cultural fatigue, particularly among younger generations.

Cultural practices also remain deeply gendered, although this is shifting. Women’s contributions were previously associated with domestic labor and caregiving, cooking, sewing, and caretaking, while men were more often linked to spiritual and ceremonial leadership, such as performing rituals and managing clan customs. However, many participants noted changes in these roles over time, citing increasing gender flexibility and a move towards shared responsibilities, especially among younger Hmong Americans. These changes were attributed to factors such as Americanization, interracial marriage, and a general decline in cultural valuation among youth. While some participants insisted that gender roles had remained largely unchanged, most acknowledged a perceptible transformation in expectations, reflecting broader processes of adaptation in diaspora.

The broad consensus that both men and women are now expected to teach and maintain the Hmong language reflects a positive shift away from strictly patriarchal models of knowledge transmission. This change indicates a move toward more inclusive and collaborative cultural preservation, which may help facilitate stronger intergenerational transmission. While some perceptions of male authority remain, the overall trend suggests that traditional hierarchies are softening. Many respondents described women as especially proactive in preserving and passing down cultural knowledge, highlighting their increasing leadership in a more balanced and evolving landscape of cultural responsibility.

6. Conclusion

This study underscores the dynamic connections between gender, tradition, and cultural preservation within the Hmong American diaspora. While traditional roles continue to shape perceptions of cultural practice, particularly in areas like ritual leadership and domestic labor, these boundaries are increasingly blurred. Women appear to be central actors in the transmission of Hmong language and culture, particularly in intergenerational settings, even as men maintain prominent roles in ceremonial contexts. The data points to a growing recognition of shared cultural responsibility, as well as the adaptive strategies both men and women employ in preserving Hmong identity amid the pressures of assimilation.

One key limitation of this study is the relatively narrow age range of participants; most respondents were from younger generations. A larger sample size that includes more older participants would offer a more complete picture of language transmission and reveal how age may influence both fluency and attitudes toward preservation. It would be especially valuable to examine generational differences in language use and cultural engagement to better understand how preservation efforts can be tailored across age groups.

Importantly, the findings also reveal significant areas for future inquiry. The gender gap in language fluency, the low initiative for active language use, and the shifting role of women in ritual participation all point to emerging tensions and opportunities in how cultural heritage is sustained. As younger generations continue to redefine what it means to be Hmong in America, understanding the evolving roles of both men and women will be essential for designing more inclusive and effective strategies for cultural and linguistic preservation. This research contributes to a broader understanding of how diasporic communities negotiate heritage and adaptation, and how gender operates not just as a category of identity, but as a lens through which cultural change is experienced and enacted.

References

[1]. Culhane-Pera, K. A., Vawter, D. E., Xiong, P., Barbara Babbitt, & Mary M. Solberg. (2003). Healing by Heart: Clinical and Ethical Case Stories of Hmong Families and Western Providers (1st ed.). Vanderbilt University Press. https: //doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv16h2nfv.

[2]. Michaud, J. (2020). The art of not being scripted so much: The politics of writing Hmong language (s). Current Anthropology, 61(2), 240-263

[3]. Livo, N. J., & Cha, Dia. (1991). Folk stories of the Hmong : peoples of Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam.

[4]. Meredith, W. H., & Rowe, G. P. (1986). Changes in Lao Hmong marital attitudes after immigrating to the United States. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 17(1), 117-126.

[5]. Cerhan, J. U. (1990). The Hmong in the United States: An Overview for Mental Health Professionals. Journal of Counseling and Development, 69(1), 88–92. https: //doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1990.tb01465.x

[6]. Gary Yia Lee. (1996). Cultural Identity In Post-Modern Society: Reflections on What is a Hmong? Cultural Identity In Post-Modern Society: Reflections on What is a Hmong? Hmong Studies Journal, 1(1), 1–14.

[7]. Huszka, B., Ya’akub, Z., Hassan, R. A., & Chuchu, I. F. (2025). Linguistic Sustainability in The Malay-Speaking Nations of The Historical Nusantara: Comparative Approaches to Minority And Indigenous Language Preservation. International Journal of Social Science and Human Research, 8(5). https: //doi.org/10.47191/ijsshr/v8-i5-109

[8]. Rona, S., & McLachlan, C. J. (2018). Māori Children’s Biliteracy Experiences Moving from a Kōhanga Reo Setting to a Kura Kaupapa Māori, Bilingual, and Mainstream Education Setting: An Exploratory Study. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 53(1), 65–82. https: //doi.org/10.1007/s40841-018-0107-6

[9]. Musk, N. (2012). Performing bilingualism in Wales: Arguing the case for empirical and theoretical eclecticism. Pragmatics : Quarterly Publication of the International Pragmatics Association, 22(4), 651–669. https: //doi.org/10.1075/prag.22.4.05mus

[10]. Hamilton-Merrit, J. (1993). Tragic mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the secret wars for Laos, 1942-1992.Indiana University Press.

[11]. Vang, C. Y. (2010). Hmong America: Reconstructing community in diaspora. University of Illinois Press

[12]. Pfeifer, M. (2024). Hmong Population Trends in the 2020 US Census. Hmong Studies Journal, 26(1).

[13]. Plotnikoff, R. C., & Higginbotham, N. (2002). Protection motivation theory and exercise behaviour change for the prevention of heart disease in a high-risk, Australian representative community sample of adults. Psychology, health & medicine, 7(1), 87-98

[14]. Tapp, N. (1989). Hmong religion. Asian Folklore Studies, 59-94.

[15]. Xiong-Lor, V. (2015). Current Hmong perceptions of their speaking, reading, and writing ability and cultural values as related to language and cultural maintenance. California State University, Fresno

[16]. Xiong, X. (2018). Hmoobness: Hmoob (Hmong) youth and their perceptions of Hmoob language in a smalltown in the Midwest (Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota).

[17]. Lomawaima, K. T., & McCarty, T. L. (2006). “To remain an Indian” : lessons in democracy from a century of Native American education. Teachers College Press

[18]. Moua, M. (2018). Navigating graduate education as a first-generation, Hmong American woman: An autoethnography. Hmong Studies Journal, 19(1), 1-25.

[19]. Her, V. K., & Buley-Meissner, M. L. (2012). Hmong and American: Negotiating Identity, Community, and Culture. Minnesota Historical Society Press

[20]. Withers, A. C. (2004). Hmong Language and Cultural Maintenance in Merced, California. Bilingual Research Journal, 28(3), 425–461. https: //doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2004.10162624

[21]. A community of contrasts. (2013). https: //ajsocal.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Communities_of_Contrast_California_2013.pdf

[22]. Thao, Y. J. (2006). The Mong oral tradition : cultural memory in the absence of written language

[23]. Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2014). An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (1st ed., Vol. 3). Beacon Press.

[24]. Jenna Cushing-Leubner, Politics of desire, policies of replacement: Race, empire, and worth(iness) in Hmong language education, International Journal of Educational Research, Volume 128, 2024, 102474, ISSN 0883-0355, https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2024.102474.

[25]. Her, X. S. (2016). The first hmong-american community college students' experiences 144 and their educational success (Order No. 10117081). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1803309281).

[26]. Tatman, A. W. (2001). Hmong Perceptions of Disability: Implications for Vocational Rehabilitation Counselors. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 32(3), 22–27. https: //doi.org/10.1891/0047-2220.32.3.22

[27]. Abidia, L. (2016). Gender, Sexuality, and Inter-Generational Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans. UC Merced Undergraduate Research Journal, 8(2). https: //doi.org/10.5070/M482030778

[28]. Lo, B. (2017). Gender, Culture, and the Educational Choices of Second Generation Hmong American Girls. Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement, 12(1), 1–22. https: //doi.org/10.7771/2153-8999.1149

[29]. Yang, K. L. (2011). The impact of Hmong women's gender role endorsement on decision-making.

[30]. Pyke, K. D., & Johnson, D. L. (2003). Asian American Women and Racialized Femininities: “Doing” Gender across Cultural Worlds. Gender & Society, 17(1), 33–53. https: //doi.org/10.1177/0891243202238977

[31]. Gary Yia Lee. (2005). The Shaping of Traditions: Agriculture and Hmong Society The Shaping of Traditions: Agriculture and Hmong Society. Hmong Studies Journal, 6(1), 1–33

[32]. Duffy, J., Harmon, R., Ranard, D., Thao, B., & Yang, K. (2004). The Hmong. An introduction to their history and culture. Center for Applied Linguistics. Retrieved from http: //www.cal.org/co/hmong/hmong_FIN.pdf

[33]. Kou Yang. (1997). Hmong Mens’ Adaptation to Life in the United States Hmong Mens’ Adaptation to Life in the United States. Hmong Studies Journal, 1(1), 1–22.

[34]. Suh, S. (2007). Too Maternal and Not Womanly Enough: Asian-American Women's Gender Identity Conflict. Women & Therapy, 30(3/4), 35-50. https: //doi.org/10.1300/J015v30n04_04

[35]. Yalom, Yalom, Marilyn, & Carstensen, Laura L. (2002). Inside the American couple : new thinking/new challenges (1st ed..). University of California Press.

[36]. Minutaglio, R. (2021, August 12). How a Hmong American woman is preserving her people’s history. ELLE. https: //www.elle.com/culture/tech/a37274117/hmong-phrases-app-annie-vang/

Cite this article

Tang,D. (2025). Between Generations and Genders: Hmong Cultural and Language Preservation in the US. Communications in Humanities Research,75,52-66.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICADSS 2025 Symposium: Consciousness and Cognition in Language Acquisition and Literary Interpretation

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Culhane-Pera, K. A., Vawter, D. E., Xiong, P., Barbara Babbitt, & Mary M. Solberg. (2003). Healing by Heart: Clinical and Ethical Case Stories of Hmong Families and Western Providers (1st ed.). Vanderbilt University Press. https: //doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv16h2nfv.

[2]. Michaud, J. (2020). The art of not being scripted so much: The politics of writing Hmong language (s). Current Anthropology, 61(2), 240-263

[3]. Livo, N. J., & Cha, Dia. (1991). Folk stories of the Hmong : peoples of Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam.

[4]. Meredith, W. H., & Rowe, G. P. (1986). Changes in Lao Hmong marital attitudes after immigrating to the United States. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 17(1), 117-126.

[5]. Cerhan, J. U. (1990). The Hmong in the United States: An Overview for Mental Health Professionals. Journal of Counseling and Development, 69(1), 88–92. https: //doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1990.tb01465.x

[6]. Gary Yia Lee. (1996). Cultural Identity In Post-Modern Society: Reflections on What is a Hmong? Cultural Identity In Post-Modern Society: Reflections on What is a Hmong? Hmong Studies Journal, 1(1), 1–14.

[7]. Huszka, B., Ya’akub, Z., Hassan, R. A., & Chuchu, I. F. (2025). Linguistic Sustainability in The Malay-Speaking Nations of The Historical Nusantara: Comparative Approaches to Minority And Indigenous Language Preservation. International Journal of Social Science and Human Research, 8(5). https: //doi.org/10.47191/ijsshr/v8-i5-109

[8]. Rona, S., & McLachlan, C. J. (2018). Māori Children’s Biliteracy Experiences Moving from a Kōhanga Reo Setting to a Kura Kaupapa Māori, Bilingual, and Mainstream Education Setting: An Exploratory Study. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 53(1), 65–82. https: //doi.org/10.1007/s40841-018-0107-6

[9]. Musk, N. (2012). Performing bilingualism in Wales: Arguing the case for empirical and theoretical eclecticism. Pragmatics : Quarterly Publication of the International Pragmatics Association, 22(4), 651–669. https: //doi.org/10.1075/prag.22.4.05mus

[10]. Hamilton-Merrit, J. (1993). Tragic mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the secret wars for Laos, 1942-1992.Indiana University Press.

[11]. Vang, C. Y. (2010). Hmong America: Reconstructing community in diaspora. University of Illinois Press

[12]. Pfeifer, M. (2024). Hmong Population Trends in the 2020 US Census. Hmong Studies Journal, 26(1).

[13]. Plotnikoff, R. C., & Higginbotham, N. (2002). Protection motivation theory and exercise behaviour change for the prevention of heart disease in a high-risk, Australian representative community sample of adults. Psychology, health & medicine, 7(1), 87-98

[14]. Tapp, N. (1989). Hmong religion. Asian Folklore Studies, 59-94.

[15]. Xiong-Lor, V. (2015). Current Hmong perceptions of their speaking, reading, and writing ability and cultural values as related to language and cultural maintenance. California State University, Fresno

[16]. Xiong, X. (2018). Hmoobness: Hmoob (Hmong) youth and their perceptions of Hmoob language in a smalltown in the Midwest (Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota).

[17]. Lomawaima, K. T., & McCarty, T. L. (2006). “To remain an Indian” : lessons in democracy from a century of Native American education. Teachers College Press

[18]. Moua, M. (2018). Navigating graduate education as a first-generation, Hmong American woman: An autoethnography. Hmong Studies Journal, 19(1), 1-25.

[19]. Her, V. K., & Buley-Meissner, M. L. (2012). Hmong and American: Negotiating Identity, Community, and Culture. Minnesota Historical Society Press

[20]. Withers, A. C. (2004). Hmong Language and Cultural Maintenance in Merced, California. Bilingual Research Journal, 28(3), 425–461. https: //doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2004.10162624

[21]. A community of contrasts. (2013). https: //ajsocal.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Communities_of_Contrast_California_2013.pdf

[22]. Thao, Y. J. (2006). The Mong oral tradition : cultural memory in the absence of written language

[23]. Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2014). An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (1st ed., Vol. 3). Beacon Press.

[24]. Jenna Cushing-Leubner, Politics of desire, policies of replacement: Race, empire, and worth(iness) in Hmong language education, International Journal of Educational Research, Volume 128, 2024, 102474, ISSN 0883-0355, https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2024.102474.

[25]. Her, X. S. (2016). The first hmong-american community college students' experiences 144 and their educational success (Order No. 10117081). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1803309281).

[26]. Tatman, A. W. (2001). Hmong Perceptions of Disability: Implications for Vocational Rehabilitation Counselors. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 32(3), 22–27. https: //doi.org/10.1891/0047-2220.32.3.22

[27]. Abidia, L. (2016). Gender, Sexuality, and Inter-Generational Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans. UC Merced Undergraduate Research Journal, 8(2). https: //doi.org/10.5070/M482030778

[28]. Lo, B. (2017). Gender, Culture, and the Educational Choices of Second Generation Hmong American Girls. Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement, 12(1), 1–22. https: //doi.org/10.7771/2153-8999.1149

[29]. Yang, K. L. (2011). The impact of Hmong women's gender role endorsement on decision-making.

[30]. Pyke, K. D., & Johnson, D. L. (2003). Asian American Women and Racialized Femininities: “Doing” Gender across Cultural Worlds. Gender & Society, 17(1), 33–53. https: //doi.org/10.1177/0891243202238977

[31]. Gary Yia Lee. (2005). The Shaping of Traditions: Agriculture and Hmong Society The Shaping of Traditions: Agriculture and Hmong Society. Hmong Studies Journal, 6(1), 1–33

[32]. Duffy, J., Harmon, R., Ranard, D., Thao, B., & Yang, K. (2004). The Hmong. An introduction to their history and culture. Center for Applied Linguistics. Retrieved from http: //www.cal.org/co/hmong/hmong_FIN.pdf

[33]. Kou Yang. (1997). Hmong Mens’ Adaptation to Life in the United States Hmong Mens’ Adaptation to Life in the United States. Hmong Studies Journal, 1(1), 1–22.

[34]. Suh, S. (2007). Too Maternal and Not Womanly Enough: Asian-American Women's Gender Identity Conflict. Women & Therapy, 30(3/4), 35-50. https: //doi.org/10.1300/J015v30n04_04

[35]. Yalom, Yalom, Marilyn, & Carstensen, Laura L. (2002). Inside the American couple : new thinking/new challenges (1st ed..). University of California Press.

[36]. Minutaglio, R. (2021, August 12). How a Hmong American woman is preserving her people’s history. ELLE. https: //www.elle.com/culture/tech/a37274117/hmong-phrases-app-annie-vang/