1.Introduction

Since the nineteenth century, women in the U.S. have made gradual progress in politics, with increased status and opportunities for women in the political arena. The emergence of this phenomenon meant that American feminism united women in their efforts to achieve their desired position in the public sphere. The growing demand and ambition of women for political equality influenced the definition and gradual recognition of women’s roles in society. Much of the existing literature focuses on individual case studies of successful political women in the U.S. and relies on quantitative analyses of regression equations when discussing women’s political participation in general. This paper, however, will use feminist theory to demonstrate women’s political participation in the U.S. before and after the feminist intervention and analyse how it reduced barriers to women’s political participation by organising women’s institutions and promoting equality issues based on the three waves of movements that fought for women’s rights. Ultimately, the study confirms the importance of feminism in defending women’s political rights and successfully bringing them into the public world. This research will also serve as a reference point for a future review of the status and remuneration of women in politics based on feminist theories.

2.Women’s Political Participation in the United States

2.1.Political Participation of Women in the U.S. Before the Rise of Feminism

Obviously, women’s political engagement in the U.S. did not start out well. When women expressed their political aspirations, society traditionally defined them as being solely responsible for running the household and caring for the children, and their choices were ignored. Specifically, not only do they not have access to political rights, but they also do not have the time and energy to engage in political activities [1]. Quantitative research on gender and politics provides a structural explanation for the inequality of resources between men and women in society due to factors such as education, income, and employment experience, which continue to affect society’s definition of women’s qualifications as leaders and political candidates [2,3]. This means that women in the U.S. have never received encouragement in politics due to cultural and legal barriers brought about by society. Conversely, those women who have become involved in public politics still have to accept the reality of the flawed and discriminatory prying eyes of male colleagues and the scrutiny and criticism of their superiors. Veness and Sweeney explained “politics is a game of strategy which men have long known how to play”, and women are sacrificed in this game [1]. Simply put, even though these women have values and behaviours that are appropriate for campaigning, they are still marginalised in a sphere of life that is dominated by male values and behavioural patterns [4]. Furthermore, women’s careers can only be favourable if they reach the elite level. For example, Geraldine Ferraro worked actively with the leadership of the House Democrats during their work and the general election, which led her to become the chair of the Democratic Platform Committee in 1984 [1]. Thus, political women have to take into account more aspects than men in the process of politicisation, and they have clear calculations and considerations about obstacles as well as goals.

2.2.Women’s Political Participation in the U.S. after the Rise of Feminism

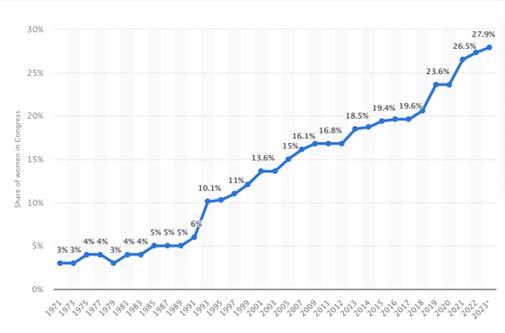

Nonetheless, women in American political society have gradually been valued in the feminist movement. Specifically, the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 gave women the right to vote and run for office as voters. Although there were still a few women in society who were afraid to make political choices due to the pressure of public opinion and the male-dominated political arena, women’s awareness of political participation was gradually awakened and no longer tended to be fearful and numb. By the mid-1960s, the role of the modern women’s movement had changed American society’s view of women in politics. The percentage of those who did not recognise the role of women in politics was decreasing and women were beginning to succeed in politics. This is because the rise of the feminist movement reduced the gap between women and men in terms of political ambitions, allowing women to become more and more attracted to the power part of society [5]. Not only that, but female voters in politics tend to show respect for policy as well as implementation, they make choices and ensure party unity because they are based on values. Women who participate in politics tend to remain sensitive to policy and partisanship, and are more liberal and effective than men in dealing with the design of violence and force [6-10]. As shown in Figure 1, the percentage of women in the U.S. Congress has been increasing steadily since the 1970s, and by 2023 women will account for nearly 30% of Congress [11]. However, some believe that women avoid the high-pressure lifestyle that comes with being active in the political arena because women candidates generally do not have a better chance of winning than men, preventing them from holding more seats in Congress and state legislatures. Conversely, there is evidence of a rising and levelling trend in women’s participation in congressional and state government positions, explaining women’s aspirations for power and efforts to dispel society’s negative stereotypes of female politicians.

Figure 1: Share of women in the United States Congress from 1971 to 2023 [11].

3.The Impact of the Feminist Movement on Women’s Political Participation in the United States

3.1.Reasons for the Emergence of Feminism in American Women’s Political Participation

The feminist movement has been able to improve women’s participation in politics in the U.S. because of its continuing impact on women’s social status and ideology through the continuity of several waves of the movement throughout history. To be specific, the first wave of the feminist movement was initiated by well-educated women in society. Their concern and call for the fight for the right to vote united women and attempted to do so by amending the federal constitution. As they realised that women as a class were suffering from discrimination in society and that women would always be turned away on important occasions with humiliating connotations. Thus, in 1848 Elizabeth Cady Stanton convened the Woman’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls and made the first public demand for women’s right to vote, which set off a political movement for women’s suffrage in American society [12]. At the same time, this wave of women’s movement accelerated the development of women’s higher education by establishing women’s colleges to broaden their minds and raise their awareness of their rights. Nevertheless, critics point out that the wave made little contribution to women’s political participation in the early years of the feminist movement due to internal differences in needs and opinions arising from women’s varying levels of education and strong opposition from conservative attitudes in society. However, the second movement of feminism had a significant role to play under the impetus of industrialisation. Driven by industrialisation, traditional housewives chose to enter society and earn a salary, giving them the opportunity to be economically independent rather than dependent on the family. The respect and importance that women gradually gained made them realise the importance of seeking equal rights for themselves in society. In addition, American women’s contribution to the war effort during World War I, when they filled a large number of job vacancies caused by men being drafted, changed society’s view of them. The awakening of women at all levels of society to political participation and the growing organisational strength of the women’s movement led Congress to pass the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution granting women the right to vote and initially recognising women’s political status. Until the third wave of feminism, the definition of gender continued to be challenged and expanded, with feminists focusing on the recruitment of women candidates, the search for resources, and public and grassroots political activism.

3.2.The Role of Feminism in Promoting Women’s Political Participation in the U.S.

3.2.1.Women’s Organisations

The most common practice of feminists is to set up national women’s organisations and encourage them to vote and stand for election. Members of the organisations seek increased opportunities for appointment and financial support for women who run for office by putting pressure on the government. One of the most influential feminist organisations in the U.S. is the National Organization for Women (NOW), which was founded in 1966. The organisation’s Statement of purpose, issued in 1966, cited the importance of eliminating discrimination against women in education, taxes, and employment, which encouraged women to run for government positions, including Congress and the Senate [13]. In other words, the purpose of NOW was to allow women to fully participate in all aspects of American society and to establish equal partnerships with men in order to exercise their rights and responsibilities. Moreover, EMILY’s List is committed to providing training, resources, and funding for women to run for Democratic government positions. It is well documented that EMILY’s List has been the largest financial source for female candidates since the late 1980s [14]. Specifically, the training and development provided by the organisation has been effective in helping candidates acquire the necessary political skills including presentation skills, policy understanding and interaction with the public to increase the competitiveness of female candidates. Meanwhile, women raise funds to promote their campaigns to leverage the media and the public to increase social recognition of women political leaders and enhance their representation in the political arena.

3.2.2.Promotion of Equality Issues

Additionally, their activities are also focused on the development and promotion of equality issues. Feminists work to change the segregation of women by promoting gender equality in the political, economic and social spheres. Specifically, they fight against discrimination between men and women in terms of job content and pay, while preserving women’s right to vocational education and training. Further, feminists advocate for a gender equality agenda, which has increased public attention to the gender trade-offs among voters and political decision-makers. In this way, they increase the proportion of appointments for women running for political office in both the Republican and Democratic parties and bring substantial decision-making power. Holtzman explained this by saying that only women themselves can truly motivate the political system to move beyond its bureaucratic inertia and subsequently enact laws to promote women’s equality [15]. It is noteworthy that the Affirmative Action Programs and the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) have emerged as relevant programmes and policies in the U.S., and even though the latter has not been successfully implemented, they have served to prohibit any form of discrimination that impedes women’s equality of opportunity, guaranteeing equal opportunities for women and minorities in the fields of employment and education. This proves that feminists have incorporated racial, ethnic and gender groups into a more inclusive conception of feminism and increased women’s political participation through the realisation of equality [16].

3.3.The Significance of Feminism in Promoting the Politicisation of Women in the U.S.

Feminism provides theoretical and ideological support for women’s active struggle for political rights. Feminists believe that campaigns for women’s dignity and equality should not be viewed merely as a project of specific interests, but rather as a tool to guarantee women’s right to participate in political institutions more broadly. However, feminists are still divided on the extent, reasons, and ways of ameliorating the disparity between men’s and women’s rights, and the overall rate of women’s political participation in the U.S. remains low [17]. Take the number and percentage of women in the U.S. Congress shown in Figure 1 as an example, even though the trend has been increasing year by year, there are only 146 female officials out of 535 seats, which is still a huge imbalance between men and women, demonstrating that women are far from being able to achieve fully equal status with men in Congress [18]. The road to women’s political participation in the U.S. is still a long one, but Holtzman is convinced that feminist ideology will stimulate a deeper demand for political freedom and equality, which will lead women to express power desires and political ambitions that are equal to or even greater than those of male counterparts, and will make them even more determined to participate in the affairs of the nation and to serve in public office.

4.Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper focuses on the changes in women’s political participation in the U.S. before and after the help of feminism and the reasons for its effective help. In addition, the article also mentions the importance of feminism’s specific approach to women’s entry into political careers through the organisation of institutions and the implementation of equality regulations. The article concludes that American political women have indeed benefited from the eliminated hindrances by the feminist movement and have been able to have a wider range of opportunities to enter politics. Conversely, the time span covered in this study is broad and some of the specific or particular instances where women’s political participation stagnated could not be addressed and discussed on a case-by-case basis. Therefore, for future projects on this topic, it would be useful to examine specific experiences in conjunction with interviews with feminists within a precise period.

References

[1]. Veness, F.P.L. and Sweeney, J.P. (1987) “1 women in the political arena”, in Le Veness, F. and Sweeney, J. (eds.) Women Leaders in Contemporary U.S. Politics. Boulder, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 1-8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685859480-002.

[2]. Welch, S. (1977) “Women as Political Animals? A Test of Some Explanations for Male-Female Political Participation Differences”, American Journal of Political Science, 21(4), pp. 711-730. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2110733.

[3]. Welch, S. (1978) “Recruitment of Women to Public Office: A Discriminant Analysis”, Western Political Science Quarterly, 31(3), pp. 372-380. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/106591297803100307.

[4]. Han, L. (2010) “3 Women as Political Participants”, Women and US Politics: The Spectrum of Political Leadership. Boulder, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 45-68. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685856861-005.

[5]. Costantini, E. (1990) “Political women and Political Ambition: Closing the gender gap”, American Journal of Political Science, 34(3), pp. 741-770. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2111397.

[6]. Frankovic, K.A. (1982) “Sex and Politics. New Alignments, Old Issues”, PS, 15(3), pp. 439–448. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/418905.

[7]. Gilligan, C. (1982) In a Different Voice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

[8]. Smith, T.W. (1984) “The polls: Gender and attitudes toward violence”, Public Opinion Quarterly, 48(1), pp. 384-396. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2748632.

[9]. Shapiro, R.Y. and Mahajan, H. (1986) “Gender Differences in Policy Preferences: A summary of trends from the 1960s to the 1980s”, Public Opinion Quarterly, 50(1), pp. 42-61. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/268958.

[10]. Gilens, M. (1988) “Gender and Support for Reagan: A comprehensive model of presidential approval”, American Journal of Political Science, 32(1), pp. 19-49. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2111308.

[11]. CAWP. (2022) Share of women in the United States Congress from 1971 to 2023. Statista. Statista Inc.. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/952906/us-congress-share-women-congress/.

[12]. History. (2022) “Seneca Falls Convention”, 9 March. Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/seneca-falls-convention#declaration-of-sentiments.

[13]. Rix, S.E. (1987) The American Woman 1987-88: A Report in Depth. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

[14]. Li, J.Q. (2009) “er shi shi ji ba shi nian dai mei guo fu nv can zheng Zhuang kuang yan jiu”, zhe xue yu ren wen ke xue; she hui ke xue I ji. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C475KOm_zrgu4lQARvep2SAk6at-NE8M3PgrTsq96O6n6bEscBknr6V2pLNqAruYaaR9iVXwjbhSX3G0lADwGcNd&uniplatform=NZKPT.

[15]. Bertolini, J.C. (1987) “6 Elizabeth Holtzman: Political Reform and Feminist Vision”, in Le Veness, F. and Sweeney, J. (eds.) Women Leaders in Contemporary U.S. Politics. Boulder, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 65–76. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685859480-007.

[16]. Han, L. (2010) “2 The Women’s Movement and Feminism in the United States”, Women and US Politics: The Spectrum of Political Leadership. Boulder, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 17–44. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685856861-004.

[17]. Holvino, E. (2007) “13 Women and Power New Perspectives on Old Challenges”, in Kellerman, B. and Rhode, D.L. (eds.) Women and Leadership: The State of Play. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey- Bass, pp. 361-382. Available at: http://www.chaosmanagement.com/images/stories/pdfs/Women%20and%20Powerchapterfinalproof4-07.pdf.

[18]. CAWP (no date) Women in the U.S. Congress 2022. Available at: https://cawp.rutgers.edu/facts/levels-office/congress/women-us-congress-2022.

Cite this article

Feng,S. (2023). The Impact of Feminism on Women’s Political Participation in the United States. Communications in Humanities Research,14,192-197.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Veness, F.P.L. and Sweeney, J.P. (1987) “1 women in the political arena”, in Le Veness, F. and Sweeney, J. (eds.) Women Leaders in Contemporary U.S. Politics. Boulder, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 1-8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685859480-002.

[2]. Welch, S. (1977) “Women as Political Animals? A Test of Some Explanations for Male-Female Political Participation Differences”, American Journal of Political Science, 21(4), pp. 711-730. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2110733.

[3]. Welch, S. (1978) “Recruitment of Women to Public Office: A Discriminant Analysis”, Western Political Science Quarterly, 31(3), pp. 372-380. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/106591297803100307.

[4]. Han, L. (2010) “3 Women as Political Participants”, Women and US Politics: The Spectrum of Political Leadership. Boulder, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 45-68. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685856861-005.

[5]. Costantini, E. (1990) “Political women and Political Ambition: Closing the gender gap”, American Journal of Political Science, 34(3), pp. 741-770. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2111397.

[6]. Frankovic, K.A. (1982) “Sex and Politics. New Alignments, Old Issues”, PS, 15(3), pp. 439–448. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/418905.

[7]. Gilligan, C. (1982) In a Different Voice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

[8]. Smith, T.W. (1984) “The polls: Gender and attitudes toward violence”, Public Opinion Quarterly, 48(1), pp. 384-396. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2748632.

[9]. Shapiro, R.Y. and Mahajan, H. (1986) “Gender Differences in Policy Preferences: A summary of trends from the 1960s to the 1980s”, Public Opinion Quarterly, 50(1), pp. 42-61. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/268958.

[10]. Gilens, M. (1988) “Gender and Support for Reagan: A comprehensive model of presidential approval”, American Journal of Political Science, 32(1), pp. 19-49. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2111308.

[11]. CAWP. (2022) Share of women in the United States Congress from 1971 to 2023. Statista. Statista Inc.. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/952906/us-congress-share-women-congress/.

[12]. History. (2022) “Seneca Falls Convention”, 9 March. Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/seneca-falls-convention#declaration-of-sentiments.

[13]. Rix, S.E. (1987) The American Woman 1987-88: A Report in Depth. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

[14]. Li, J.Q. (2009) “er shi shi ji ba shi nian dai mei guo fu nv can zheng Zhuang kuang yan jiu”, zhe xue yu ren wen ke xue; she hui ke xue I ji. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C475KOm_zrgu4lQARvep2SAk6at-NE8M3PgrTsq96O6n6bEscBknr6V2pLNqAruYaaR9iVXwjbhSX3G0lADwGcNd&uniplatform=NZKPT.

[15]. Bertolini, J.C. (1987) “6 Elizabeth Holtzman: Political Reform and Feminist Vision”, in Le Veness, F. and Sweeney, J. (eds.) Women Leaders in Contemporary U.S. Politics. Boulder, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 65–76. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685859480-007.

[16]. Han, L. (2010) “2 The Women’s Movement and Feminism in the United States”, Women and US Politics: The Spectrum of Political Leadership. Boulder, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 17–44. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685856861-004.

[17]. Holvino, E. (2007) “13 Women and Power New Perspectives on Old Challenges”, in Kellerman, B. and Rhode, D.L. (eds.) Women and Leadership: The State of Play. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey- Bass, pp. 361-382. Available at: http://www.chaosmanagement.com/images/stories/pdfs/Women%20and%20Powerchapterfinalproof4-07.pdf.

[18]. CAWP (no date) Women in the U.S. Congress 2022. Available at: https://cawp.rutgers.edu/facts/levels-office/congress/women-us-congress-2022.