1. Introduction

The flute, tracing back to the bone flutes of Jiahu in Wuyang, Henan, around eight thousand years ago, stands as the oldest known musical instrument in China.[1] According to historical records in the “Records of the Grand Historian,” during the time of the Yellow Emperor, people began usingbamboo to craft flutes, marking the transition from bone to bamboo and the gradual formation of bamboo flutes. During the Han Dynasty, transverse flutes emerged, and by the Han and Tang periods, “da hengchui” and “xiao hengchui” in the court music repertoire referred to transverse flutes, indicating the widespread use of flutes during that time. Chen Yang’s “Yue Shu” documented the appearance of bamboo flutes featuring membrane-like structures during the Tang Dynasty. The rise of theatrical music during the Song and Yuan periods elevated the flute to a prominent role as an accompanying instrument. In the 20th century, the flute evolved from being an accompaniment in Kunqu opera and Bangzi opera to a solo instrument, creating distinct playing styles characterized by the mellifluousness of the qudi and the vibrant energy of the bangdi. Throughout history, the six-hole flute has been the fundamental form of traditional Chinese bamboo flutes, while the eight-hole flute has evolved from the six-hole flute. The eight-hole flute not only captures the charm of traditional Chinese bamboo flutes but also enables the performance of music in the twelve-tone equal temperament. Therefore, this article focuses on examining the reform of bamboo flutes and the development of flute music through the transition from the six-hole to the eight-hole bamboo flute configuration.

2. Basic Structures of Six-Hole and Eight-Hole Flutes

The six-hole flute originated during the Yuan Dynasty and has a structure similar to modern six-hole flutes. Despite the changing tides of history, it has not disappeared but instead has refined its resilience. Although the bamboo flute has only six finger holes, it can produce a variety of ethnic music styles, encompassing the elegance of ancient court music and the simplicity of folk music, as well as the graceful melodies of Southern music and the robust, high-pitched tunes of Northern music. This versatility underscores the significant historical importance of the six-hole bamboo flute.[2]

Today, influenced by Western musical culture, Chinese music has diversified, presenting a profusion of works with increasing technical complexity and difficulty. With the introduction of compositions based on the twelve-tone equal temperament, traditional six-hole flutes can no longer meet the demands of composers and performers. Consequently, the design of flutes has undergone continuous improvements, leading to the emergence of seven-hole flutes, nine-hole flutes, ten-hole flutes, eleven-hole flutes, and keyed flutes, among various other designs. Through practical experimentation and research, the eight-hole flute has been developed to retain the distinctive features of traditional bamboo flutes while facilitating the performance of compositions based on the twelve-tone equal temperament.[3]

2.1. Basic Structure of the Six-Hole Flute

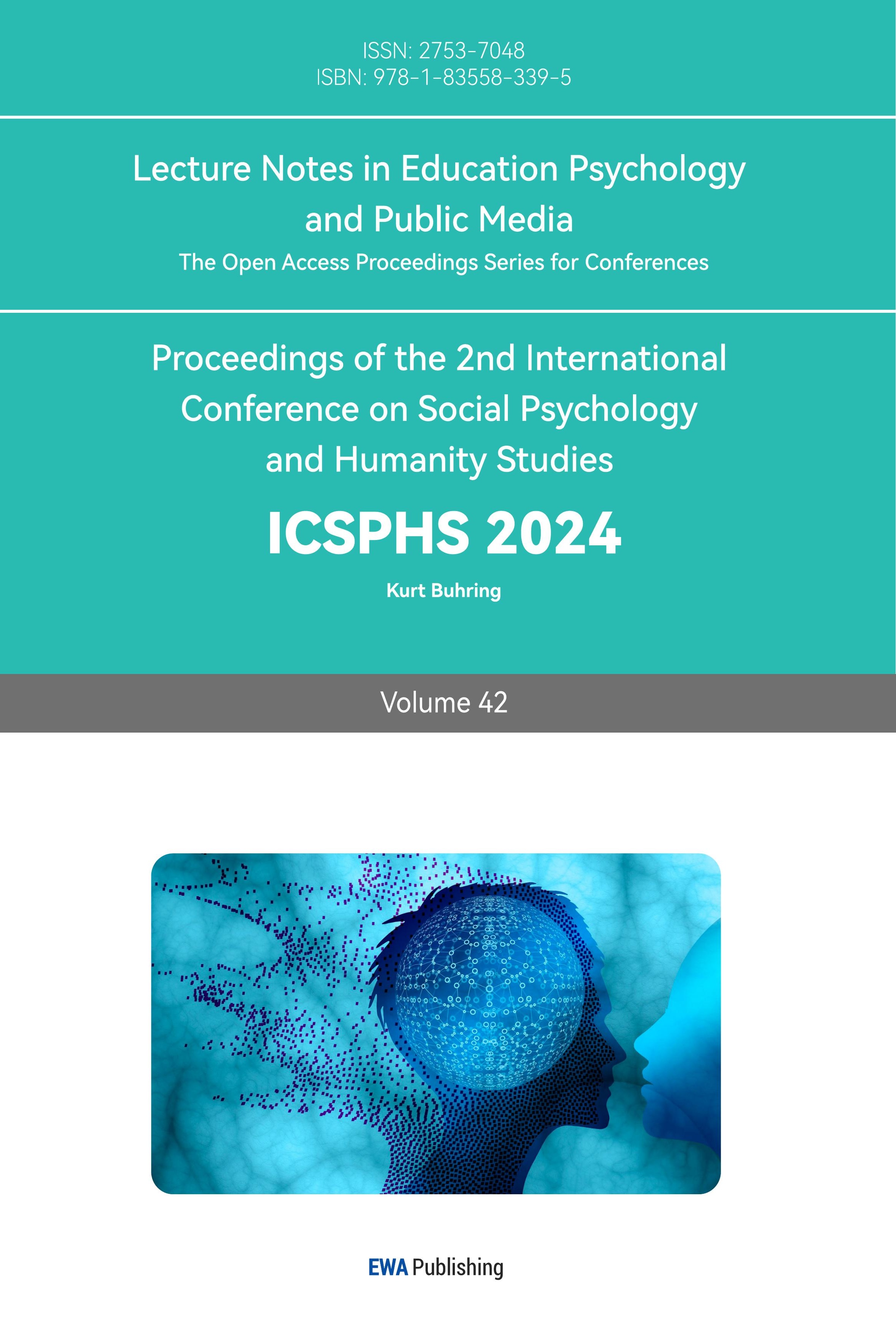

The six-hole bamboo flute is crafted from a single bamboo tube with an empty inner chamber. The flute body consists of a blowing hole, a membrane hole, six finger holes (seven holes for low-pitched flutes such as D and F), two fundamental pitch holes, and two auxiliary pitch holes. The flute’s ends are adorned with insets typically made from materials such as ox horn, ox bone, or jade.

The blowing hole, located at the left end of the bamboo flute, allows the player to introduce air into the flute, causing vibrations in conjunction with the membrane and the flute body, producing sound. The membrane hole, the second hole from the left on the flute, is used for attaching a membrane to adjust the tone color of the bamboo flute. The membrane is made from the inner membrane of reeds, cut into small pieces and affixed to the membrane hole to create a crisp and bright sound. The finger holes, six in total, are manipulated primarily by the index, middle, and ring fingers of both hands. Closing and opening these holes allows the player to produce different pitches. The fundamental pitch holes are utilized for precise pitch modulation, defining the lowest notes of the flute. Positioned beneath the fundamental pitch holes, the auxiliary pitch holes are used to raise the pitch, enhancing the beauty of higher notes and increasing the volume of the flute’s sound. The structure is illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Six-hole flute [4]

2.2. Basic Structure of the Eight-Hole Flute

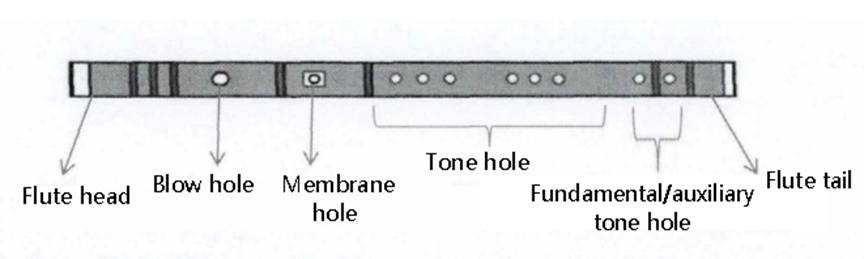

The design of the eight-hole bamboo flute is built upon the foundation of the six-hole flute. Currently, there are two main variations of the eight-hole flute. One type involves the addition of two holes on the backside of the traditional six-hole flute, controlled by the thumb. However, this design increases pressure on the thumb during use, making it less conducive to extended playing, and the author believes it is not optimal. The second variation, developed by renowned flutist and doctoral supervisor at the Central Conservatory of Music, Professor Dai Ya, introduces two additional finger holes. One small finger hole is located below the first hole on the side, controlled by the right little finger, producing a pitch one semitone higher than the first hole. The second hole is situated between the third and fourth holes on the side, controlled by the left little finger, producing a pitch half a tone higher than the fourth hole. [5]The structure is depicted in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Eight-hole flute [4]

2.3. Comparison between the Six-Hole Flute and the Eight-Hole Flute

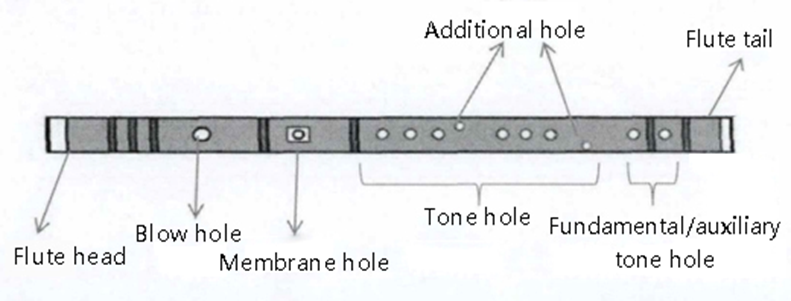

As illustrated in the above diagram, the basic structure of the six-hole flute and the eight-hole flute is essentially the same, with the only difference being the addition of two holes. Therefore, the fingering for the eight-hole flute is built upon the scale arrangement of the six-hole flute. Both flutes are capable of playing the twelve-tone equal temperament. Taking the 5-finger technique as an example, the fingering for the six-hole and eight-hole flutes is depicted in Figures 3:

Figure 3: Fingering for the Six-Hole Flute and Fingering for the Eight-Hole Flute

The scale arrangement for the six-hole and eight-hole flutes (using g-finger technique) is as follows: g, #g, a, #a, b, c1, #c1, d1, #d1, e1, f1, #f1. In the six-hole flute, playing # g and #c requires using the ring finger to cover half a hole, resulting in a less solid tone and difficulties in intonation, sometimes leading to inaccuracies. In contrast, the eight-hole flute allows for precise playing of #c1 ,#c2 ,#g1and #g by simply lifting the little finger, facilitating the execution of changing tones in rapid musical passages. The fingering for other notes remains the same for both flutes.

Through comparison, the eight-hole flute exhibits significant advantages: Firstly, whether performing modern or traditional compositions, the same flute can be used. If a piece does not require #g and #c1 fingerings, the two small holes can be sealed. Secondly, it is convenient and straightforward, maintaining the inherent fingering order of the traditional six-hole flute. This allows learners to adapt more quickly compared to flutes with ten or eleven holes, which can increase finger pressure and alter fingering sequences. Thirdly, it enhances the flute’s expressive techniques, enabling better execution of vibrato for minor seconds. Fourthly, by adding two small holes, incomplete scales can be perfected, facilitating the realization of traditional Chinese transpositions starting from the dominant note. As an example, consider the seven-note scale in the key of C major:

C major-G major-D major-A major-E major-B major-#F major-#C major-#G major-#D major-#A major-#E major-#B major (equivalent to C major) [6]

3. Application of the Eight-Hole Flute in Flute Music

The success of the improvement on the eight-hole flute requires validation through practical application. Through performance and teaching, the author has experienced that the eight-hole flute, whether in contemporary solo bamboo flute pieces or in ethnic chamber music or orchestras, is capable of handling the aforementioned tasks, proving the success of the enhancement.

3.1. Application of the Eight-Hole Flute in Six-Hole Flute Repertoire

The 20th century witnessed the creation of numerous bamboo flute compositions, such as “Gusu Xing,” “Mai Cai,” “Under the Great Qing Mountain,” and even some concertos like “Zou Xi Kou” and “Shaanbei Four Chapters.” Additionally, works from the 21st century, like “Xue Yi Duan Qiao,” are all originally intended for six-hole flute performance. When using the eight-hole flute for these pieces, the additional two holes can be sealed or kept pressed down by the little finger, or opened if required by certain compositions.

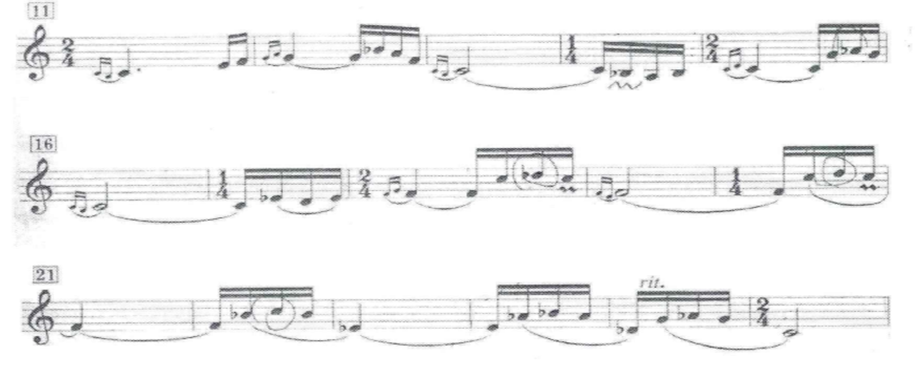

Furthermore, the need for half-hole playing is not limited to chromatic alterations in bamboo flutes; it also arises in some transposition fingerings. For instance, in the music piece “Oasis,” originally intended for six-hole flute performance and embodying the Xinjiang musical style, the fingering for the G major Bangdi, fully closed as f, involves a problematic half-hole at the fourth hole marked as #g1 in the notation (Figure 4). The stability of intonation and timbre is compromised in this half-hole position. However, when using the eight-hole flute, simply opening the left little finger can produce the required note, enhancing both intonation and timbre stability.

Figure 4: Oasis

In the cyclic double-tonguing section of the third phrase, with the fingering as fully closed d, the notes #g1 and #d2 correspond to the newly added two holes. This eliminates the challenge of rapid transitions associated with half-holing by the ring finger in the six-hole flute, thus preventing intonation issues (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Oasis

By performing this piece on the eight-hole flute, it not only facilitates the execution of chromatic alterations but also preserves the original style of the composition.

3.2. Application of the Eight-Hole Flute in Contemporary Solo Pieces

3.2.1. Integration of Chinese Traditional Music with Western Composition Techniques

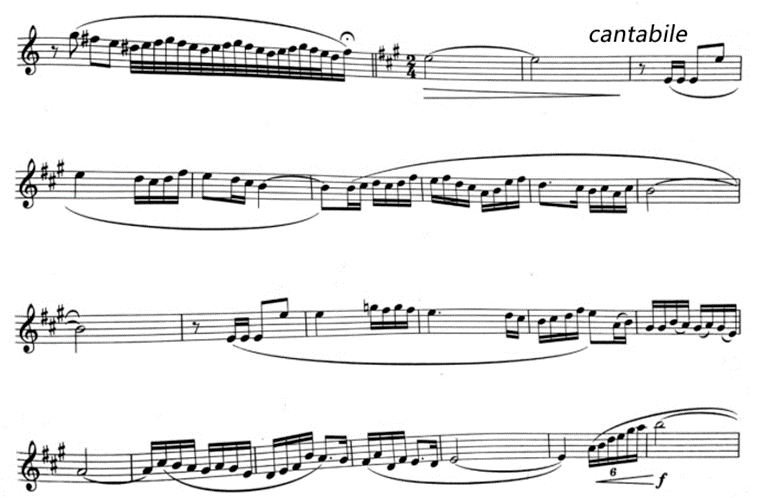

“A Shi Ma Narrative” is a modern bamboo flute solo piece composed by Yi Ke, Yi Jiayi, and Zhang Baoqing, intended for a ten-hole flute. The composition retains traditional flute playing techniques while incorporating Western composition techniques, significantly increasing the difficulty of performance. Playing this piece on a six-hole flute would prove challenging. Despite being composed for a ten-hole flute, the author believes that the increased finger load and the higher number of holes in a ten-hole flute could negatively impact the flute’s vibrational sound production. Therefore, the author experimented with performing it on the eight-hole flute, and the results showed that the piece could be executed seamlessly (Figure 6).

The notes bb1, bb,ba1,bd1and bd2 in this section can all be played on the eight-hole flute. Particularly noteworthy is the process from g1 to ba1 in the 15th measure, where the left and right little fingers of the eight-hole flute can produce a minor second glissando, showcasing the style of Chinese ethnic music.

Figure 6: A Shi Ma Narrative[7]

3.2.2. Transplanted Music Compositions

“Hu Xuan Wu”, composed by Mr. Zhong Yaoguang in 2007 for the Western flute, was later transplanted by Professor Dai Ya for performance on the eight-hole flute. The successful premiere at the National Grand Theater in 2009 contributed to the advancement of the eight-hole flute.

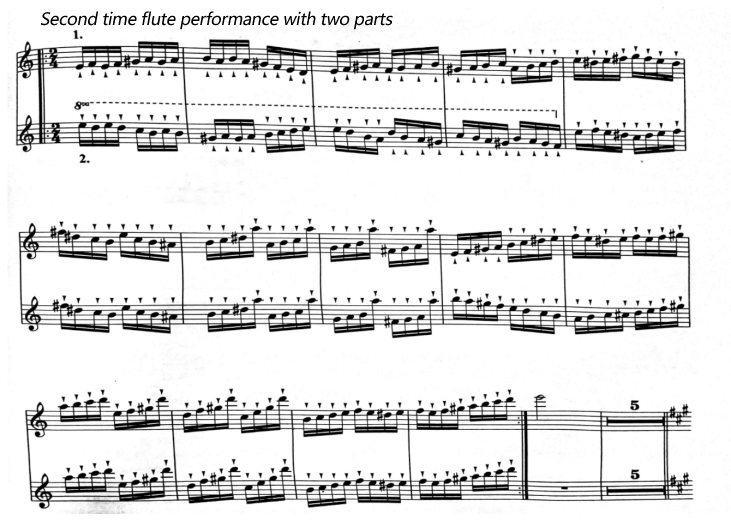

“Hu Xuan Wu” is a dance originating from the Western Regions during the Tang Dynasty, transmitted to the Central Plains through the Silk Road. The accompanying music and dance gained popularity. Transplanted for bamboo flute performance in F major, it consists of two sections. The first section, in a slow tempo, features numerous chromatic alterations, portraying a rich Western Regions ambiance. It possesses strong narrative qualities with elements like thirty-second notes, sixteenth-note triplets, and septuplets, contributing to the piece’s vivid and colorful expression (Figure 7). Performing this on a six-hole flute would result in increased difficulty during transitions between half-hole positions, resulting in a less clear and coherent musical line. Given the eight-hole flute’s ability to handle chromatic alterations more effectively, it avoids intonation and timbre instability while accurately presenting the rich Western Regions ambiance.

Figure 7: Hu Xuan Wu

The second section of the composition (Figure 8) is a lively part that introduces new materials. Through techniques such as modulation and variation, it employs wide-ranging leaps, features extended high notes, and highlights the advantages of the eight-hole bamboo flute with a plethora of chromatic alterations.[4]

Figure 8: Hu Xuan Wu

Whether in “A Shi Ma Narrative” or “Hu Xuan Wu”, these compositions pose significant challenges for traditional six-hole bamboo flutes. The challenges primarily lie in controlling the musical style, varying rhythms, the span of the pitch range, and the extensive use of chromatic alterations. However, when performed on the eight-hole flute, such works balance nimble and convenient playing techniques, substantially addressing the shortcomings of the traditional six-hole bamboo flute and promoting the development of Chinese bamboo flutes.

3.3. Application of the Eight-Hole Flute in Ensemble Pieces

Apart from solo performances, bamboo flutes play a crucial role in ensembles and ethnic orchestras. When facing compositions by modern composers, the ability of bamboo flutes to present them perfectly tests not only the performers’ skill but also the development of bamboo flute instruments.[8]

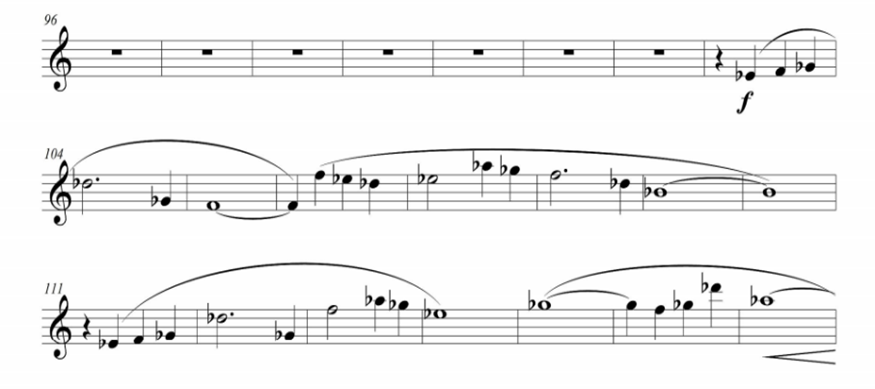

“De Yin”, composed by the outstanding young composer Li Bochan in 2014 for ethnic chamber music, features instruments such as yangqin, zhongruan, erhu, zhonghu, flute, and sheng. The piece emphasizes coordination in texture, rhythm, and harmony, demanding precision but also incorporating numerous half-tones, creating challenges for the flute section.

Initially, the author attempted to perform it using a six-hole bamboo flute, but faced difficulties in achieving optimal results, especially in playing the #g and #c chromatic alterations.

Figure 9: De Yin

As demonstrated in Figure 9, performing with a six-hole bamboo flute is extremely challenging. However, employing the fingering of fully closed d on the eight-hole G major flute, issues with be1, be2 and ba2 can be effortlessly resolved, avoiding problems with intonation and timbre during chromatic alterations. This also enhances the accuracy of transitions between chromatic alterations and ensures smoother finger movements.

From the discussion above, it is evident that since the 1990s, a plethora of modern bamboo flute compositions has emerged. Renowned composer Guo Wenjing created the bamboo flute concerto “Chou Kong Shan”, which was performed in collaboration with a Western symphony orchestra, featuring Professor Dai Ya as the soloist. This marked the first collaboration between a Chinese traditional instrument and a Western symphony orchestra, and the piece is a typical twelve-tone equal temperament work that achieved great success. In 1991, composer Li Binyang, currently residing in the United States, specially composed the eight-hole flute concerto “Chu Hun” for Professor Dai Ya, further promoting the use of the eight-hole flute. Some solo works, transplanted pieces, ensemble works, and even concerto works in collaboration with Western symphony orchestras in recent years affirm that the eight-hole flute aligns with the current trend in music development. It has also spurred the creation of new bamboo flute works and promoted reforms in bamboo flute instruments.

4. Reflections on the Development of Bamboo Flute and Flute Music

In the context of the relationship between the reform of traditional instruments and the development of ethnic music, composers, performers, and instrument makers have all undertaken extensive work. Currently, with some criticism that new ethnic music compositions are overly Westernized, focusing on technical prowess without expressing the charm of traditional music, the author reflects on this issue.

4.1. Mutual Promotion between Bamboo Flute Reform and Flute Music Composition

The improvement of the bamboo flute needs to both adapt to the development of flute music and propel that development. Traditional six-hole bamboo flutes can handle compositions in the twelve-tone equal temperament, as demonstrated by the transposition of Pablo de Sarasate’s violin piece “Song of the Wanderer” by the renowned bamboo flute educator and performer Qu Guangyi. On one hand, as numerous transplants and modern compositions continue to emerge, the six-hole flute gradually reveals limitations in meeting the demands of modern compositions. This has led to the evolution of different types of multi-hole flutes, with the eight-hole flute, particularly the one modified by Professor Dai Ya, gaining widespread use. On the other hand, the reform of the bamboo flute has also driven the development of flute music. As mentioned earlier, works such as “Chou Kong Shan,” “Hu Xuan Wu,” and “Chu Hun” were specifically composed for the eight-hole flute. In addition, Professor Yi Jiayi has also created pieces such as “A Shi Ma Narrative” specifically for the ten-hole flute. This fully illustrates the birth of multi-hole flutes, providing composers with more possibilities for their creations and further advancing the development of Chinese ethnic music.

4.2. Preserving the Essence of Ethnic Music

While the improvement of the bamboo flute caters to Western compositional techniques and facilitates the performance of twelve-tone equal temperament pieces, it should not come at the “cost” of losing the essence of Chinese ethnic music. The author believes that the essence of Chinese music cannot be conveyed simply through techniques like glissandos or vibratos; it requires a profound understanding of the musical background and genre.

4.3. Opportunities and Challenges for Bamboo Flute and Flute Music in a Diverse Cultural Context

In the article “Encounters and Dialogues in Cross-Culture: Exploring Zhang Weiliang’s Innovative Path in Chinese Folk Music,” it is mentioned, “For thousands of years, one phenomenon and issue that cannot be avoided or ignored in the development of Chinese music is the influence of others. It is not an exaggeration to say that Chinese music is the result of China’s exchanges and dialogues with the world. From over two thousand years ago, with the emergence of the Silk Road, to the 21st century under the tide of globalization, encounters and dialogues with others have shaped the past and present of Chinese music. Since the era of reform and opening up, a significant number of contemporary Chinese musicians have continuously attempted to engage in a dialogue between self and others, tradition and modernity, thereby exploring a cross-cultural path that connects China with the world.” Since the reform and opening-up, contemporary Chinese musicians have continuously attempted to engage in a dialogue between self and others, tradition and modernity, forging a cross-cultural path connecting China and the world.[9] This illustrates that the development of any music cannot avoid dialogue and exchange, and self-isolation may lead to its elimination. The improvement of the eight-hole flute, enhancing its adaptability to a wide range of musical styles (both Chinese ethnic and Western), is a result of collision and exchange with world music cultures.

5. Conclusion

As a new-generation bamboo flute performer and educator, one should bear the responsibility of continuous exploration, advancing the exchange between Chinese ethnic music and the world, mutually drawing inspiration. In the context of diverse cultural exchanges, the interaction between Chinese and foreign musical cultures, based on integration and complementarity, represents the true path for the development of human musical civilization.

References

[1]. Zhang, F. (2010). A Comprehensive Review of Improved Research on the Flute. *Journal of Xinghai Conservatory of Music, 2010*(04), 127-132.

[2]. Chang, Y. W. (2020). The Emergence and Application of the Eight-Hole Bamboo Flute. *Drama Home, 2020*(03), 40-42.

[3]. Yang, C. Z. (2019). The Scale Journey of the Eight-Hole Bamboo Flute. [Master’s thesis, Central Conservatory of Music, 2019].

[4]. Gu, S. N. (2019). On the Influence of the Eight-Hole Bamboo Flute on the Development of Bamboo Flute Art. [Master’s thesis, Central Conservatory of Music, 2019].

[5]. Luo, J. X. (2020). Research on the Practical Exploration of Improving and Adding Holes to the Bamboo Flute. [Master’s thesis, Xi’an Conservatory of Music, 2020]. DOI: 10.27402/d.cnki.gxayc.2020.000103. (https://doi.org/10.27402/d.cnki.gxayc.2020.000103).

[6]. Dai, Y. (2003). Collaboration and Reflection on the Flute and Western Orchestras. *People’s Music, 2003*(04), 19-23+63.

[7]. Zhang, Y. Y. (2015). Reflections and Explorations of Flute Art in the “New Situation” and “New Requirements.” [Master’s thesis, Central Conservatory of Music, 2015].

[8]. Hou, C. Q. (2018). On the Role of the “Eight-Hole” Bamboo Flute in Ethnic Orchestras. *Musical Instruments, 2018*(12), 46-50.

[9]. Ma, L. (2022). Encounter and Dialogue in Cross-Culture: Viewing Zhang Weiliang’s Innovation in Chinese Folk Music from World Music. *Chinese Music, 2022*(03), 179-181+192. DOI: 10.13812/j.cnki.cn11-1379/j.2022.03.022. (https://doi.org/10.13812/j.cnki.cn11-1379/j.2022.03.022).

Cite this article

Wang,Z. (2024). Evolution of Chinese Bamboo Flutes and Flute Music from Six-Hole to Eight-Hole Flutes. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,42,32-41.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zhang, F. (2010). A Comprehensive Review of Improved Research on the Flute. *Journal of Xinghai Conservatory of Music, 2010*(04), 127-132.

[2]. Chang, Y. W. (2020). The Emergence and Application of the Eight-Hole Bamboo Flute. *Drama Home, 2020*(03), 40-42.

[3]. Yang, C. Z. (2019). The Scale Journey of the Eight-Hole Bamboo Flute. [Master’s thesis, Central Conservatory of Music, 2019].

[4]. Gu, S. N. (2019). On the Influence of the Eight-Hole Bamboo Flute on the Development of Bamboo Flute Art. [Master’s thesis, Central Conservatory of Music, 2019].

[5]. Luo, J. X. (2020). Research on the Practical Exploration of Improving and Adding Holes to the Bamboo Flute. [Master’s thesis, Xi’an Conservatory of Music, 2020]. DOI: 10.27402/d.cnki.gxayc.2020.000103. (https://doi.org/10.27402/d.cnki.gxayc.2020.000103).

[6]. Dai, Y. (2003). Collaboration and Reflection on the Flute and Western Orchestras. *People’s Music, 2003*(04), 19-23+63.

[7]. Zhang, Y. Y. (2015). Reflections and Explorations of Flute Art in the “New Situation” and “New Requirements.” [Master’s thesis, Central Conservatory of Music, 2015].

[8]. Hou, C. Q. (2018). On the Role of the “Eight-Hole” Bamboo Flute in Ethnic Orchestras. *Musical Instruments, 2018*(12), 46-50.

[9]. Ma, L. (2022). Encounter and Dialogue in Cross-Culture: Viewing Zhang Weiliang’s Innovation in Chinese Folk Music from World Music. *Chinese Music, 2022*(03), 179-181+192. DOI: 10.13812/j.cnki.cn11-1379/j.2022.03.022. (https://doi.org/10.13812/j.cnki.cn11-1379/j.2022.03.022).