1. Introduction

Language is intricately intertwined with people’s daily lives. As the importance and focus on language have grown, linguists have gradually shifted their emphasis from the use of language to its internal exploration. Ferdinand de Saussure, a Swiss linguist and one of the most influential figures in the history of modern linguistics, authored Course in General Linguistics, which helped establish linguistics as an independent academic discipline and made significant contributions to its development [1]. Saussure’s work continues to hold immense value for philosophy and social sciences to this date. He considered language to be a system of signs and introduced the concept of the symbolic system, thus marking the beginning of semiotics. In the 1960s, the evolution of semiotics led to a surge in structuralism, with scholars like Roman Jakobson elevating its status to the peak of academic study [2]. Within Saussure’s semiotic framework, the renowned psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan was initially inspired by his theories and later proposed new research and corrections to Saussure’s symbolic system. Therefore, this paper aims to explore the structure and characteristics of the symbolic system through Lacan’s perspective. It presents and deeply interprets Lacan’s early exploration and innovation of Saussure’s linguistic signs within the symbolic system and anticipates the contributions and innovations of Lacanian psychoanalysis to political philosophy and the critique of ideology from the perspectives of structuralism and the master signifier.

2. Saussure’s Primacy of the Signified in Linguistics

2.1. Saussure’s Language

What is language? Instead of directly answering this question, when faced with such conceptual inquiries, such as “What is water?” or “What is an apple?”, the reader can first try to imagine and think about the structure of the answers to these kinds of questions. It becomes evident that the answers to such questions can change depending on the object of the question, leading to a diversity of responses. Within this diversity, there exists a kind of universal structure, which can be illustrated with a simple example: “What is water?” For a chemistry teacher or a chemist, water is H2O. When asked further: “What is water?” they might say, “Water is H2O, and H2O is composed of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom.” However, it can be deduced that this is not the final answer, and it could be further explained how it is composed. As it can be seen, as long as human curiosity is pursued, this sentence composed of symbols will continue to extend. With the expansion of the answer, more and more symbols are filled in, constantly extending to form the answer to the question. This infinitely extending chain of symbols represents the universality within.

Returning to the original question, what is language? This universal structure, in the sense of Saussure, is language (langue). Language is like an infinitely extending chain of symbols. One symbol follows another, and the interpretation of this or these symbols depends on other new symbols, which in turn need further explanation by even more symbols [3]. They extend continuously, thereby forming an infinite process of signification where one symbol points to another. Therefore, in response to the question, “What is language?”, it can be defined that this kind of infinitely extending chain-like structure is language.

2.2. Signifier and Signified

Linguistic signs are formed by the combination of the signified and the signifier. In this context, Saussure considered the signified as the concept, while the signifier represents written symbols and sound patterns [4]. When the signifier represents a sound pattern, it focuses on the psychological aspect of sound. It is not a physical sound, but a purely psychological impression. In other words, it is the mental representation formed after experiencing certain specific objects. This psychological manifestation is reflected in the ability to silently recite a poem or read a sentence in one’s mind even when the vocal cords stop vibrating and no sound is produced. The signified, on the other hand, refers to the concept or meaning, and it similarly focuses on the psychological aspect of things [5]. In the symbolic system, a certain signifier corresponds to a certain signified, and Saussure proposed that the combination of signifier and signified is arbitrary, though this arbitrariness is not absolute [6]. For example, greeting phrases differ between Eastern and Western cultures, with Chinese people commonly saying “Have you eaten?” or “Where are you going?”, while Westerners might say “Good morning”, “How are you doing?” or “What’s up?” Here, the connection between the signifier and the signified is established on the differences in cultural and social customs. Furthermore, in the symbolic system, a signifier without a concept cannot exist as a linguistic unit, and the concept and meaning must also be combined with certain sounds or written symbols. Thus, the physical form of linguistic signs (the signifier) and the concepts they express (the signified) form a complex and interconnected whole.

2.3. The Primacy of the Signified

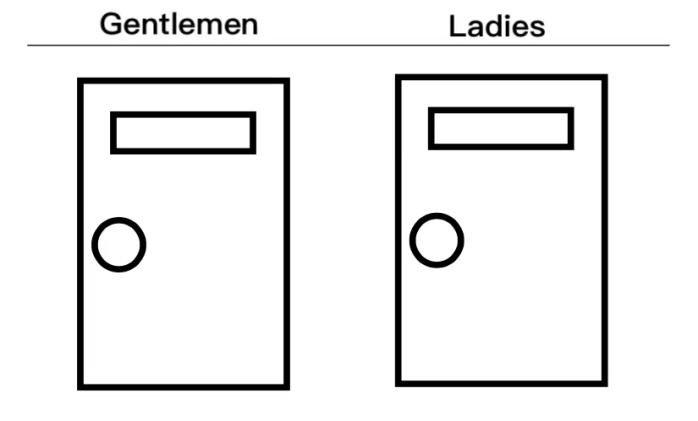

Delving further into the structure of linguistic signs, it becomes apparent that in Saussure’s illustration of the signified and signifier, he placed the signifier below and the signified above, as he considered the signified, or the concept, to be of primary importance [1]. The explanation of a concept does not rely on a fixed signifier. For instance, if assumes that there exists a pure concept of “dog”, a purely signified entity, this “pure” refers to a signified that has not been symbolized, a concept not expressed through a signifier. There are many signifiers that can represent this pure concept, such as the English “dog” or even the symbol “-1”. Anyone can invent a signifier to denote the concept of “dog”. This example also simply illustrates the arbitrariness of the signifier, meaning the expression of a concept does not depend on a fixed signifier. The combination of the signified and the signifier does not have a necessary or intrinsic connection; the same concept can have many different signifiers. Therefore, Saussure placed the signifier below and the signified above to illustrate the primacy of the signified (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Saussure’s Linguistic Sign (Photo Credit: Original)

3. Between Two Doors: The Concept and Meaning are the Effects of Two Different Signifiers

3.1. The Example of the Two Doors

Figure 2: Two Identical Doors (Photo Credit: Original)

Confronting Saussure’s high regard for the “signified” in the avenue of linguistics, the renowned French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan held a different view. He pointed out that the signifier is not only not secondary, but on the contrary, it is primary. Regarding the priority of the signifier, he once made a somewhat puzzling explanation through a simple example (see Figure 2). A train arrives at the station. A little boy and a little girl, brother and sister, are sitting face to face by the window in the carriage. Through the window, they can see the houses along platform 6 passing by as the train slowly stops. The brother says, “Look, we have arrived at the ladies’ toilet.” The sister replies, “NO! Can’t you see we have arrived at the men’s toilet?”[7] The ambiguity in this example becomes evident when considering Lacan’s treatment of the signified as two doors and ‘ladies’ and ‘gentlemen’ as signifiers. However, the siblings’ conversation alone does not serve as direct proof of the primacy of the signifier: some thought processes have been ignored. Therefore, this example leads us to ponder the reason behind representing two different signified concepts, ‘gentlemen’ and ‘ladies,’ with identical doors. It prompts people to consider whether the metaphor intentionally utilizes identical doors as symbolic objects.

3.2. Between Two Doors: The Effect of the Signifier

Lacan posited that the signifier is vital in introducing differentiation, underscoring its paramount importance [8]. The example of the two doors precisely illustrates this truth: the concept or meaning is merely the effect of the interaction between two different signifiers. It is the emergence of the symbols “men” and “women” that allows the two distinct concepts to be revealed and differentiated from one another.

First, envision a pure signified, where purity implies the de-symbolization of the signified. In other words, it’s a concept that exists without the necessity of language expression, devoid of the need for signifiers as intermediaries. The position of the signifier is vacant. Furthermore, even though there is a picture of a tree representing the signified, in fact, this picture itself acts as a signifier: Seeing this image prompts individuals to contemplate the concept of a tree. Consequently, the concept of the tree, the pure signified, is also fundamentally absent in this context. This leads to the question: What is this pure concept without relying on signifiers for comprehension? The answer is that this pure concept is nothing. Without signifiers as intermediaries, a purely de-symbolized concept is completely unimaginable. and even if it could be imagined, it would be like a blank page, with nothing on it. However, this blankness is still not blank enough. When discussing true nothingness, then it is not just a blank space as a description. In the realm of the pre-symbolic, in a pre-symbolic world, any linguistic description of this world is also illegal. The best description would be a kind of first-person experience of silence, just like a Buddha contemplating while facing a wall in the deep mountains, because there is nothing here, not even the so-called signifier “here” or the signifier “is”. Therefore, using a blank page to explain the pre-symbolic world is also inappropriate, there is no category of “colour”, no white, no whiteness but rather nothing at all, that is “nothingness” itself. If necessitated to envision a pure, unmediated concept or idea, it can only be as depicted as a mass of paste or a pot of porridge, an indescribable clump [9]. This is what the most primal thought or idea looks like, without any shape, and its interior also lacks any distinct contours as imagination, because there is only one unformed mess, unable to split and differentiate within itself. Undoubtedly, this mirrors the truth behind the metaphor involving those two identical doors.

Before the introduction of difference by the signifiers, there is no internal distinction in thought, because there aren’t two distinct concepts here. The reason why people have two different concepts is entirely because two different signifiers introduced this difference. This is why Lacan used two identical doors as the signifieds because, in the absence of the signifier, there are not two different concepts. Only one pure “being” or “nothingness” from the start or just an unorganized clump like this. The expression of two completely different concepts can only be through two different signifiers. Here, it becomes apparent that a concept or meaning is the effect between different signifiers, concept or meaning is itself an absence; it does not exist.

Lacan once used a story by segment Freud to express the above viewpoint. Freud’s nephew, about 18 months old, was playing a game with a reel of thread. The little guy threw one end of the reel out and said “Fort”, which means “gone” in German, and then he pulled it back and said “Da”, meaning “here” in German.

Lacan used this to illustrate that it is precisely these two different signifiers, fort and da or two different sound-images, that at the moment of their creation, give consciousness or thought its internal two different outlines and two different concepts thus emerge and are distinguished from each other. Concept or meaning is merely the effect of these two different signifiers, or rather, it is formed by the signifier and the differences between them.

Concluding from the above discussion, the idea that the signified has primacy is becoming less convincing. As linguistics continues to develop, especially following Lacan’s approach, the significance of the signifier becomes increasingly evident, as illustrated in the ‘two doors’ example. Lacan, using evidence that supports the significance of the signifier, has made adjustments to Saussure’s original concepts of the signifier and the signified [9].

Figure 3: Lacan’s Linguistic Sign (Photo Credit: Original)

As depicted in Figure 3, the signifier is denoted by the capital letter S, positioned above the signified. Conversely, the signified is symbolized by the lowercase letter s, situated below the signifier. Meanwhile, a hyphen “/” is used to create a division between the signifier and the signified. Here, the hyphen acts like a boundary, hindering the connection between the signifier and the signified, and also illustrating the fundamental split between them [7].

3.3. Structuralism

The question of what is language has been addressed. The structure of language, as an infinitely extending chain composed of signifiers, is what Lacan refers to as the “chain of signifiers” or the “symbolic system” [10]. The signified is merely an effect of this chain of signifiers. This effect depends on the differences between signifiers. To elaborate further, it relies on a system of differences in synchrony. This perspective is the essence of structuralism. For example, if one considers four signifiers: a, b, c, and d, and four signifieds: 1, 2, 3, and 4. However, it becomes evident that this configuration is impossible, as the signified is fundamentally absent. Therefore, the focus should be directed solely toward the signifiers. From the structuralist viewpoint, the four signifiers ‘abcd’ together constitute a system of differences, and this system is called a system of differences because any symbol within this collection needs to rely on the differences with other symbols to establish its own identity. In other words, the seemingly self-evident principle of identity, as in ‘a=a’, actually has a premise of difference. There is a logic of negation here, namely, identity is born from negation/difference. Therefore, a is an only because it is not b, it is not c and it is not d. A signifier becomes itself, or gains its value, based on its difference from or negation of, other symbols [11].

Furthermore, this collection of symbols is itself a synchronic network of differences. What is synchronicity? To understand this concept better, it is essential to explore its antithesis, diachronicity. These two concepts can be illustrated with a simple example: when someone walks down a road and sees a tree, they express it with a series of symbols, saying, “This is a tree.” This illustrates diachrony: it refers to the existence of a causal chain, meaning that the generation of symbols is prompted by an external object and its processes. Someone believes he is saying “This is a tree” because he saw a living tree, and this tree, after being perceived by him, prompted his mind to generate a symbol. However, the principle of synchronicity maintains that the expression of “this is a tree” solely results from a synchronous network of differences. Among the differences in other symbols, this specific entity is identified as a tree: this tree is not the blue sky behind it, not the leaves fallen on the ground, not the bark or the trunk, nor the brown colour of this trunk, but simply a tree.

3.4. Master Signifier

Where does this synchronic structure originate from, and how is it formed? One can imagine a signifier. This signifier is referred to by Lacan as the Master Signifier, S1. denoted as S1. Given the inherent absence of the signified, when this signifier begins to try to point to a signified, it fails. However, a very surprising situation arises from this failure. The failed attempt to point to the signified turns into a successful act of pointing, namely, to the act of pointing itself. That means although there is no endpoint to be reached, and though the movement towards an endpoint has failed, the movement itself, the act of signification, succeeds. Consequently, if it tries to stop the process of signification, aiming to reach the endpoint of ‘signifying itself,’ this is also impossible. When the goal of this process is the process itself, then the signification must keep going endlessly to have itself to point to and reach. Essentially, it becomes both its cause and its effect. In conclusion, what the master signifier represents is the infinite process of signification, that is, the chain of the signifier, the synchronic system of differences itself.

However, why does the master signifier initially point to something, rather than doing nothing? Where does the energy for this act of signifying come from? From a philosophical vantage point, it originates from the subject, or rather, from humans. Humans are precisely this constant motion of signifying. In other words, this act of signifying is the desire itself.

Moreover, the fact that the master signifier points to an absence reveals another hidden truth beyond the genesis of the symbolic system. That is, the chain of signifiers represented by the master signifier is rootless, floating baselessly in the air.

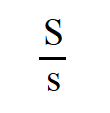

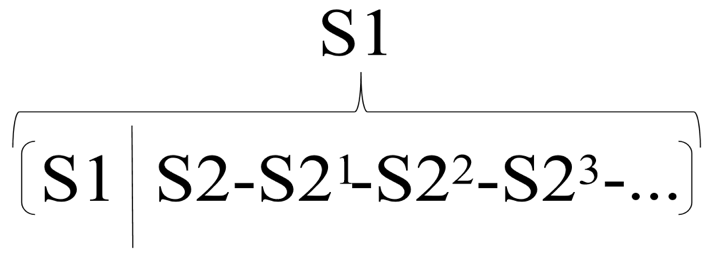

Firstly, as a signifier, the master signifier self-nestedly disguises itself as a regular signifier to exist within this system of differences (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Master Signifier (Photo Credit: Original)

However, since it represents the entire system, it cannot truly occupy a position equivalent to other signifiers within this system, since the master signifier is fundamentally different from other signifiers. Therefore, it cannot achieve self-identity among the differences with other symbols. the master signifier can only act as its basis to explain itself. It is itself here pure symbolic violence and is fundamentally separated from other signifiers. An example to illustrate the aforementioned argument: during one’s youth, when life adhered to familial arrangements, perhaps the daily routine was always the same: eating, washing dishes, sleeping, and going to school. Everything seemed to follow a certain pattern, a causal chain. Nevertheless, at a certain juncture, one may question this routine, seeking answers from father: “Dad, why must I eat before going to sleep?” In response, the father may explain, “Because you have school tomorrow.” If the questioning persists, the father’s patience may wane, culminating in a definitive response: “Because what Dad says is what Dad says, and you must obey.

“Dad”, as the Master Signifier s1, represents pure symbolic violence. The series of signifiers represented by this violence are not as logically coherent as they appear, because their origin is an absolute dictator. This master signifier acts as its basis. “Dad is dad” It’s like a king issuing orders regardless of others’ advice, because the king is the king, and you shall not resist”.

4. Conclusion

Lacan’s introduction of the master signifier not only unveils a certain universal truth but also, in terms of its historical significance, enables the possibility of modern ideological critique: the master signifier is like a hollow space, which signifier fills this space in determined by the dispute between discourses. This dispute is the battle of ideology. On the other hand, Lacan’s theory enables the possibility of defining ideology and points out that any mind captured by ideology falls into a misconception. These individuals tend to believe that the master signifier is inherently full and filled with meaning. However, as Lacan reveals, the master signifier cannot be anchored to any specific signified because it is fundamentally absent and is not ‘full.’ Instead, it represents a form of pure symbolic violence and cannot be interpreted by other symbols but can only refer to itself in a self-referential manner. Lacan’s psychoanalytic theory, with its precise definition of ideology, has aided subsequent generations in establishing a foundation for the critique of ideology. In summary, this paper aims to innovatively interpret Lacan’s example of the two doors by revisiting Ferdinand de Saussure’s concept of linguistic signs in linguistics, especially his view on the primacy of the signified. Based on this interpretation, the reader can understand why the signifier takes precedence and, from this precedence, grasp the genealogical mechanism of the symbolic system in a straightforward and comprehensive manner. Ultimately, this paper seeks to review and anticipate the establishment and development of modern ideological critique based on Lacan’s concept of the master signifier.

References

[1]. Saussure, F. (1916) Course in General Linguistics. Peter Owen Limited.

[2]. Marrone, G. (2020) Structure/Structuralism. Glossary of Morphology. 491-495.

[3]. Lagopoulos, A. & Boklund-Lagopoulou, K. (2021). Theory and Methodology of Semiotics: The Tradition of Ferdinand de Saussure. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

[4]. Susen, S. (2018) Saussure, Ferdinand de. In: Turner, B. S., Kyung-Sup, C., Epstein, C. F., Kivisto, P., Outhwaite, W. & Ryan, J. M. (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Theory. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

[5]. De Andrade, S. & Oliveira, C. (2020) Signo Linguístico: Saussure E Lacan Linguistic Sign: Saussure and Lacan. Discursos Verbais E Verbovisuais.

[6]. Ahmad, M. (2020) Deconstructing Bond of Signifier & Signified: a Corpus-Based Study of Variation in Meaning. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture, 6(4), 76-87.

[7]. Lacan, J. (2006) Ecrits: The First Complete Edition in English. WW Norton & Company.

[8]. Rapaport, H. (2018) Structuralism and Semiotics. The Bloomsbury Handbook of Literary and Cultural Theory.

[9]. Barnouw, J. (1981) Signification and Meaning: A Critique of the Saussurean Conception of the Sign. Comparative Literature Studies, 18(3), 260.

[10]. Lacan, J., & Miller, J.-A. (Ed.). (1993) The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book 3: The Psychoses 1955-1956. W. W. Norton & Company.

[11]. Nicolar, C. (2019) Structuralism, A New Philosophical Perspective On The World And Sciences In The Early 20th Century. InterCulturalia, 2018, 189.

Cite this article

Yi,X. (2024). From Saussure to Lacan: The Primacy of the Signifier. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,43,208-214.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Saussure, F. (1916) Course in General Linguistics. Peter Owen Limited.

[2]. Marrone, G. (2020) Structure/Structuralism. Glossary of Morphology. 491-495.

[3]. Lagopoulos, A. & Boklund-Lagopoulou, K. (2021). Theory and Methodology of Semiotics: The Tradition of Ferdinand de Saussure. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

[4]. Susen, S. (2018) Saussure, Ferdinand de. In: Turner, B. S., Kyung-Sup, C., Epstein, C. F., Kivisto, P., Outhwaite, W. & Ryan, J. M. (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Theory. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

[5]. De Andrade, S. & Oliveira, C. (2020) Signo Linguístico: Saussure E Lacan Linguistic Sign: Saussure and Lacan. Discursos Verbais E Verbovisuais.

[6]. Ahmad, M. (2020) Deconstructing Bond of Signifier & Signified: a Corpus-Based Study of Variation in Meaning. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture, 6(4), 76-87.

[7]. Lacan, J. (2006) Ecrits: The First Complete Edition in English. WW Norton & Company.

[8]. Rapaport, H. (2018) Structuralism and Semiotics. The Bloomsbury Handbook of Literary and Cultural Theory.

[9]. Barnouw, J. (1981) Signification and Meaning: A Critique of the Saussurean Conception of the Sign. Comparative Literature Studies, 18(3), 260.

[10]. Lacan, J., & Miller, J.-A. (Ed.). (1993) The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book 3: The Psychoses 1955-1956. W. W. Norton & Company.

[11]. Nicolar, C. (2019) Structuralism, A New Philosophical Perspective On The World And Sciences In The Early 20th Century. InterCulturalia, 2018, 189.