1. Introduction

Women are extraordinarily popular painted subjects throughout art history. Guided by the mainstream values of heterosexual men in a patriarchal society, early artists were often obsessed with the beautiful body of women and tried their best to show the most idealized female form in their mind. In people's imaginations, the goddesses in mythology have almost perfect plump images: smooth and translucent skin and perfectly proportioned features. As for women with low social status, their appearances are still attractive. However, the paintings often imply that they live and work as male’s appendages. They are forcibly assigned to the responsibility of breeding offspring for family and endowed with dirty and morbid imagination by men.

2. In the Renaissance: mythical color of women

The Renaissance was a period when the status of rational science rose and religious beliefs collapsed, but there was still no lack of mythology in paintings. This kind of mythical beauty is undoubtedly wondrous to a certain extent. Raffaello Santi’s works are very good examples, which emphasize at the vivid depiction of idealized female appearances, especially their dynamic beauty in movements. This kind of beauty is not confined in harmonious composition, rounded facial outline and glossy, smooth skin, or the static statue like image of the Virgin, but also involves complex expressions and postures seemingly captured from a series of actions. In the fresco The Nymph Galatea, Galatea had just got up from water, wrapped in red cloth waving in wind and riding a celestial beast underneath her feet with hands. Meanwhile, the artist shows a scene where natural environment and gods reconcile in order to enhance the visual authenticity: the sea gods stretch out half of the body from water and flirt with nymphs, sneering the love song from the clumsy giant Polyphemus to Galatia. Several little love gods holding Cupid's arrows are hidden behind the clouds in sky, alluding to the affair depicted in the painting. Raffaello clearly elaborates a beautiful, powerful goddess who is also a little arrogant and capricious, free to make choices in relationship, and has broken away from the traditional nature of obedience to the man.

Figure 1: The Nymph Galatea.

Pitifully, most of Raphael's paintings focus on the beauty of pure appearance, and the subjects are goddesses rather than women in real life. The emergence of rational science had not immediately made people pay attention to the disadvantaged gender group and express more humanistic thoughts in paintings. In other words, women were still not the subject of social change at the time, instead mediums for expressing appreciation for beauty.

As time goes by, people unanimously shift their attention on ordinary people in reality [2]. Jean François Millet's The Gleaners follows the trend, which expands the scope of the objects depicted, and focuses on ordinary rural women. The three peasant women in the painting have no clear faces and are bending over to pick up the crops left by the farm operator, setting off their marginalized identity in this society. However, behind the description of the women's sweat and toil is another limitation: these women still appear in traditional identities as nurturers necessary for human reproduction. Their work units are families rather than factories. Their tasks are not to manufacture goods on the assembly line to get paid, but to find food from abandoned lands for their husbands and children in the poor family regardless of return. In the harmonious nature background and warm tones, their housewife duties are even shrouded in divine brilliance [3].

Figure 2: The Gleaners.

Their sufferings are rationalized by religious righteous and nature course seemingly from time immemorial. The picture is showing them doing works that conforms to the natural order. These gleaning women have no clear face figures, but only cumbersome clothes that represent their low social status and beautiful body profiles roughly outlined by those clothes. On the other hand, the painting proves that most women in the era resemble this lifestyle. Exploited by the social environment and trapped by the land day by day, they were not as fortunate as men to have the power or means to engage in ideological revolutions, let alone acknowledging the difference between feudalism and capitalism to their livings.

3. Prescribed roles: Nurse and prostitute

The commoner women of the old society had two functions that were subordinate to the demands of patriarchal society: sexual intercourse and reproduction.

Figure 3: Found.

The occupation corresponding to the former one is a prostitute. The few words that match it are depraved, astray. Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Found depicts a young woman wandering the streets with a gaunt face, and the reason for her decadent posture is apparent. When she was recognized, she knelt in shame, looking like she was seeking repentance. The painting is clearly, in a superior pose, persuading young women who have sex with men outside of their marriage for whatever reason, to return to the right path, that is, to serve the family, so that they would still have a pure heart. Yet this is a distorted inclusion. No one pays attention to the reality that women engaged in the black industry because they are forced by the pressure of livelihood. Moreover, no one had proposed the simple law that there is demand in this market before there is supply, which means men who enjoyed the service were most criminal.

The occupation corresponding to the second one is a wet nurse. In Berte Morisot's Wet Nurse and Julie, there is no doubt that the artist's daughter and the wet mother are beautiful, but when we inspect the "right" and even noble profession of nursing mother, we can see real situation of women's career choices in past [4]. Most ordinary mothers will choose to go to rich homes in order to earn money after giving birth and use their physical functions to work and earn money for their families. Such work does not have any erotic overtones, and even bypasses the reproductive links caused by sexual talents, while fulfilling the "incomparably great" female obligation to feed offspring, with divine maternal brilliance. This just solves the contradiction between the dirty sexual element and the noble maternal element, which seems quite reasonable. There is a more interesting fact about this painting: a woman is painting another woman who is breast-feeding her daughter. In the above case, goods difficult to measure become visible. Human milk and the painting are two goods with exchange value, since Morisot and her employed wet nurse both engage in productive activities. Profits created this painting in the market.

Figure 4: Wet Nurse and Julie.

Women were often considered to have vulgar but attractive erotic charm, in line with the characteristics of women's appendages in the natural order. Under male gaze, they might be beautiful and captivating, but have no independent personality. They were regarded as similar objects, exchangeable commodities, primitive, backward symbols that cannot become the creator, innovator, or revolution leader of the times.

4. Women’s awakening and rebellion in a new era

Over time, the female appearance or universal state of life from the perspective of male artists in the Renaissance ceased to be a single melody of artistic development, and female artists also picked up brushes to express themselves.

Figure 5: Outbreak.

Kathe Kollwitz’ s Outbreak was the most groundbreaking, with women rushing forward with their weapons in pursuit of advancement [5]. There are no bright colors.in the painting. The contrasting monochromatic colors and rough brushstrokes express the women’s willingness to act freely and autonomously, as well as the sad but strong emotions of being-towards-death. Instead of focusing on ornate colors or delicate details, what we can see in the painting is an active woman who has the appeal to jump out of the natural order. The rough nicks are like sharp swords piercing the prison-like gender bias.

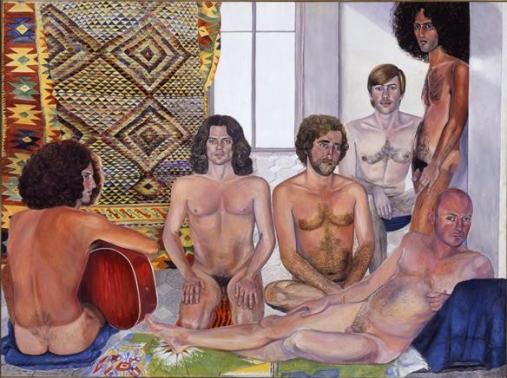

Women's counterattack lies not only in the strength of the image, but even in the change of perspective of observation. With the continuous arousal of female consciousness, the direction of traditional gaze has become completely opposite [6]. Sylvia Sleigh spearheaded the revolution of women gaze. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres painted The Turkish Bath to satisfy the illusions of men, presenting women’s humiliating posture of weakness and obedience. Sylvia’s homonymous painting contrasts strongly with the nude woman in the previous. Six men in the painting are densely haired, softened in the female perspective to weaken the heroism of mainstream male propaganda value, only depicted as objects of female sexual desire. She doesn't understand "why men's genitals are more sacred than women's", so she unabashedly shows every detail of naked men, making men passive from a female perspective.

Figure 6: The Turkish

5. Conclusion

Early women were the objectification of the male subject, rather than the protagonists of the revolution. But women are not only acting as participants in the specified framework, we are also the part of the sovereign, building a culture with men in this social system. From the Middle Ages until modern times, mythological goddesses were celebrated for idealized beauty, while ordinary women lived under the gaze of male audiences and were forced to struggle to earn a living within narrow range of career choices. With the advancement of thought, more and more female artists have bravely criticized and rebelled against female discrimination by transforming the direction of gaze. Under the leadership of these female artists, modern female community should confidently establish subjective status, bravely display desires and implement equal rights with men.

References

[1]. Even, Y. (1991). The Loggia dei Lanzi: A Showcase of Female Subjugation. Woman’s Art Journal, 12(1), 10–14. doi:10.2307/1358184

[2]. Hunt, C. (2021). Millet and Modern Art: From Van Gogh to Dalí and Jean-François Millet: Sowing the Seeds of Modern Art. Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, 20(1). doi: 10.29411/ncaw.2021.20.1.16

[3]. Katz, F., Klein, M., & Klein, H. (1977). Kathe Kollwitz. Life in Art. Art Education, 30(2), 38. doi: 10.2307/3192177

[4]. Kessler, M. (1999). Unmasking Manet's Morisot. The Art Bulletin, 81(3), 473. doi: 10.2307/3051353

[5]. Loughery, J., Bowman, R., & Adrian, D. (1991). Sylvia Sleigh: Invitation to a Voyage and Other Works. Woman's Art Journal, 12(1), 57. doi: 10.2307/1358198

[6]. Mathews, N., Stuckey, C., Scott, W., Lindsay, S., Adler, K., & Garb, T. et al. (1989). Documenting NOCHLIN, L. (2019). WOMEN, ART, AND POWER AND OTHER ESSAYS.

Cite this article

Ma,Y. (2024). From Gaze to Rebel: A Study of Female Figures in Art History. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,50,98-102.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Even, Y. (1991). The Loggia dei Lanzi: A Showcase of Female Subjugation. Woman’s Art Journal, 12(1), 10–14. doi:10.2307/1358184

[2]. Hunt, C. (2021). Millet and Modern Art: From Van Gogh to Dalí and Jean-François Millet: Sowing the Seeds of Modern Art. Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, 20(1). doi: 10.29411/ncaw.2021.20.1.16

[3]. Katz, F., Klein, M., & Klein, H. (1977). Kathe Kollwitz. Life in Art. Art Education, 30(2), 38. doi: 10.2307/3192177

[4]. Kessler, M. (1999). Unmasking Manet's Morisot. The Art Bulletin, 81(3), 473. doi: 10.2307/3051353

[5]. Loughery, J., Bowman, R., & Adrian, D. (1991). Sylvia Sleigh: Invitation to a Voyage and Other Works. Woman's Art Journal, 12(1), 57. doi: 10.2307/1358198

[6]. Mathews, N., Stuckey, C., Scott, W., Lindsay, S., Adler, K., & Garb, T. et al. (1989). Documenting NOCHLIN, L. (2019). WOMEN, ART, AND POWER AND OTHER ESSAYS.