1. Introduction

In the era of globalization and societal economic advancement, the conventional authoritarian leadership style is increasingly deemed inadequate for effectively managing the evolving workforce, particularly the new-generation employees known for their diversity and adaptability [1]. Generation Z, born in the late 1990s and early 2000s, is entering the labor force and is expected to introduce new work dynamics. According to Schroth, Generation Z employees emphasize equality, inclusion, and diversity, with 91% believing that everyone is equal, and Generation Z is also the most racially and ethnically diverse generation [2]. Therefore, inclusive leadership emphasizing openness, accessibility, and availability aligns with the pursuit of Generation Z.

Numerous studies have shown the significant positive impact of inclusive leadership on various aspects of employee behavior and attitudes. For instance, inclusive leadership has been linked to enhanced innovative behaviors [1, 3-4], increased work engagement [5-7], and heightened psychological empowerment [4, 8]. These findings underscore the importance of inclusive leadership in modern organizational settings. Despite being a relatively novel leadership approach, scholars increasingly recognize its importance.

However, despite extensive research on inclusive leadership, there remains a notable gap in the literature on reviews encompassing concepts, measurement methods, theoretical foundations, and multilevel impacts of inclusive leadership, especially under different cultural backgrounds [1, 3-8]. This limitation impedes scholars' collective understanding of existing studies on inclusive leadership behavior and underscores the need for further research in this area.

To address this gap, the primary objective of this study is to conduct a literature review of existing research on inclusive leadership based on English and Chinese databases. By explaining concepts, measurement methods, theoretical foundations, and multilevel impacts of inclusive leadership, this research attempts to provide literature support for scholars interested in exploring this topic in the future. Additionally, drawing from the insights gleaned from existing studies, this research will propose recommendations and paths for advancing current research on inclusive leadership, thereby contributing to its further development and promotion.

2. Definition and Measurement

2.1. Definition and Dimensionality

Nembhard and Edmondson’s work in 2006 first introduced the term “inclusiveness” into leadership research [9]. Leader inclusiveness refers to “words and deeds exhibited by leaders that invite and appreciate others' contributions” [10]. That is, leaders not only actively encourage and value contributions from their followers but also create an environment where “cross-disciplinary teams overcome the inhibiting effects of status differences, allowing members to collaborate in process improvement” [10].

Building upon this foundation, subsequent researchers have explored the concept of inclusive leadership from various perspectives. Hollander et al. framed inclusive leadership using the leader-member exchange theory, and defined inclusive leadership as a process of active followership emphasizing follower needs and expectations, constructive feedback, and the assumption of responsibility [11]. Within the same theoretical framework, Nishii and Mayer highlighted the ability of inclusive leaders to cultivate high-quality relationships with group members and facilitate their active involvement in decision-making processes [12]. In 2010, Carmeli et al. expanded and treated “inclusive leadership as a specific form relational leadership” [13]. Then they proposed one of the most widely accepted definitions, which refers to “leaders who exhibit openness, accessibility, and availability in their interactions with followers” [13]. However, despite these advances, some scholars raised concerns that “previous efforts to conceptualize and operationalize inclusive leadership do not have a comprehensive theoretical basis and have not clearly differentiated inclusive leadership as distinct from” [9]. That is, Randel et al. defined inclusive leadership as leaders’ deliberate efforts aimed at nurturing group members’ perceptions of both belongingness and appreciation for their unique contributions, which they termed “belongingness” and “uniqueness” [14].

The research on inclusive leadership has primarily emerged from Western academics, rooted in Western cultural insights. However, it is increasingly recognized that a growing number of Eastern scholars have incorporated the concept of inclusive leadership within the Eastern cultural context. Given the uncertainties surrounding the direct transplantation of Western leadership styles into Eastern contexts, including questions about the consistency of definitions and outcomes with Western research findings, many Eastern scholars attempted to develop inclusive leadership based on Eastern cultural background [15]. In particular, many Chinese scholars constantly try to combine Eastern culture from different perspectives and put forward some new concepts of inclusive leadership.

Some Chinese scholars are blending Eastern cultural dimensions with inclusive leadership, thereby presenting innovative models. Based on the formulation by Carmeli et al., Yao and Li advocated for a version of inclusive leadership marked by four pillars: openness, affinity, tolerance, and support within organizations and teams [16]. Fang and Jin further elaborated on inclusive leaders, describing them as individuals who equitably treat team members to achieve mutually beneficial outcomes [17]. Such leaders foster interdepartmental and interdisciplinary collaboration, cultivate and acknowledge team members, harness and leverage their strengths, and tolerate failures while providing guidance [17].

Drawing from the deep well of traditional Chinese culture, some scholars introduced their understanding of inclusive leadership. Zhu and Qian emphasized leaders’ attentiveness to the individualization and differentiation of followers, active listening, recognition of contributions, and the promotion of principles such as equality, sharing, openness, and humanization [18]. From the perspective of managing the new generation of employees, Li et al. suggested that inclusive leadership is anchored in a people-first philosophy, ensuring equitable growth opportunities [19]. Moreover, inclusive leadership is a process of “mutual support,” meaning that leaders not only uphold honesty in their conduct but also endeavor to influence subordinates to cultivate honest qualities and behaviors [19].

Some Chinese scholars have interpreted “inclusiveness” as synonymous with “acceptance” and “tolerance,” addressing both surface differences, such as gender or age, and more profound disparities, including opinions, behaviors, values, and shortcomings [4-5]. Consequently, inclusive leadership encompasses a repertoire of leader behaviors that “embrace the diversity among individuals, acknowledge the unique value of each employee, foster collaboration and communication, accommodate team members’ failures with appropriate professional guidance, and is characterized by openness, accessibility, and availability” [4].

2.2. Measurement and Study Design

Influenced by diverse cultural backgrounds and theoretical frameworks, scholars differ in their definitions of inclusive leadership, leading to varying perspectives on the dimensions to be measured (as indicated in Table 1). It's noteworthy that while some scholars have developed consistent measurement approaches based on the dimensions they have identified, others may not align their measurements with these specified dimensions. Moreover, many of these measurements lack sufficient evidence of validity or lack it altogether.

Regarding study design, most studies are quantitative, involving the use of surveys to collect relative data from employees or leaders. A smaller portion of the research is qualitative and adopts the form of interviews. Very few studies combine qualitative and quantitative research methods.

Table 1: Measurement scales of inclusive leadership.

Author (year) | Cultural context | Dimensions |

Nembhard and Edmondson (2006) | Western | Invitation and appreciation |

Hollander et al. (2009) | Western | Support-recognition, communication-action-fairness, and self-interest-disrespect |

Carmeli et al. (2010) | Western | Openness, availability, and accessibility |

Randel et al. (2018) | Western | Supporting team members, ensuring justice and equity, and shared decision-making |

Zhu and Qian (2014) | Eastern | Openness, democracy, Humanism, and justice |

Li et al. (2012) | Eastern | Balanced empowerment, ambulatory management, and progressive innovation |

Fang and Jin (2014) | Eastern | Inclusion, recognition, fairness, encouragement, and support |

Yao and Li (2014) | Eastern | Openness, affinity, tolerance, and support |

2.3. Why Inclusive Leadership is an Independent Leadership Behavior?

2.3.1. Features

Inclusive leadership is distinguished by its commitment to listening, honoring diversity, and supporting team members. Compared to other leadership styles, inclusive leadership exhibits distinctive features and principles, yet maintains consistency and stability in its application.

Firstly, inclusive leadership prioritizes hearing and valuing the opinions and insights of team members. While participatory leadership involves employees in decision-making and seeks input from employees, inclusive leaders take it a step further. Inclusive leadership strongly emphasizes effective communication, ensuring that the voice of every team member is heard, and promoting collaboration and communication among individuals with diverse backgrounds and perspectives [20]. Secondly, inclusive leadership values the diversity of team members, including cultural backgrounds, ways of thinking, and working styles, thereby promoting collaboration and communication among individuals with diverse backgrounds and perspectives [4-5, 13]. Thirdly, inclusive leadership is dedicated to supporting the growth and development of team members by providing necessary resources and inspiring employees to realize their full potential. This leadership style is not solely fixated on team outcomes but also on individual self-improvement and well-being [19]. Fourthly, inclusive leadership endeavors to build trust among teams and achieve team goals through cooperation and achieving consensus. In contrast to transactional leadership styles, which may focus on short-term results and performance, inclusive leadership places greater emphasis on fostering long-term relationships and cultivating a supportive team culture. This approach recognizes the importance of unity and shared purpose in achieving team objectives. Lastly, inclusive leadership demonstrates flexibility and adaptability, adjusting its leadership style according to different situations and the needs of team members. Inclusive leaders are attentive to the overall atmosphere and mood of the team, taking appropriate actions to promote team cohesion and effectiveness.

In essence, inclusive leadership is characterized by fostering an environment where every individual feels valued and every voice can contribute to collective success. These unique qualities set inclusive leadership apart from other types of leadership.

2.3.2. Theoretical Base of Inclusive Leadership

(a) Relational Leadership Theory

Relational leadership, integral to the essence of inclusive leadership, emphasizes the importance of continuous dialogue with subordinates to achieve shared organizational objectives. Effective leadership behavior requires fair communication with employees, an aspect increasingly acknowledged as pivotal for organizational advancement. As highlighted by Cunliffe and Eriksen, relational leaders maintain a steadfast commitment to engaging in ongoing dialogue with their team members [21]. According to research by Dong et al., as organizations evolve, relational leadership becomes increasingly relevant, aligning with the trajectory of organizational development [22].

(b) Psychological Safety Theory

Psychological safety significantly influences individuals' perceptions of their work environment. Strong psychological safety within teams is associated with increased innovation and positive leader-member exchange relationships [9]. Furthermore, it cultivates learning behavior, job engagement, and performance, underscoring its significance for inclusive leadership. Hirak et al. identified a positive correlation between inclusive leadership and employee psychological safety [23].

(c) Flexible Management Theory

Flexible management entails dynamic management strategies characterized by self-management and adaptive adjustments, emphasizing humanization and situational responsiveness [24]. This approach, as illustrated by the "differential piece rate system," recognizes the influence of variable factors and leverages both incentives and corrective measures. Consequently, flexible management can be inherently more adaptable and personalized, aligning well with the principles of inclusive leadership. In this regard, Li et al. examined inclusive leadership behaviors, such as promoting equality and fostering innovation among employees in the face of organizational uncertainty [19].

3. Theoretical Perspective of Inclusive Leadership Study

In the scholarly pursuit of inclusive leadership, a variety of theoretical lenses have been applied to illustrate proposed frameworks. A review of this theoretical groundwork reveals two dominant theories prevalent in the field: Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) and Conservation of Resources (COR) theories.

3.1. Leader-Member Exchange Theory

The Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory explores the nuanced interactions between leaders and individual followers within an organization. The theory suggests that through social exchanges, leaders and followers establish unique relationships, which substantially influence employee outcomes [25-26]. Moreover, the theory argues that when leaders and followers foster mature, partnership-like relationships, they reap significant relational benefits [27]. Consequently, LMX theory facilitates an understanding of how inclusive leadership is intertwined with distinctive exchange relationships between leaders and employees, leading to varying levels of trust, support, and communication [6].

Furthermore, LMX theory underscores the concept of differentiated leadership, wherein leaders may adopt distinct leadership styles and behaviors with in-group and out-group members [25-26]. This differentiation sheds light on how inclusive leaders' accommodation of diverse needs and preferences among followers fosters conducive conditions for employees' innovative behavior [27-29].

3.2. Conservation of Resources Theory

The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory posits that individuals are driven by a desire to acquire and maintain various resources, encompassing time, energy, material possessions, social support, and personal attributes [30]. Resources, as defined by Hobfoll, are objects, personal attributes, circumstances, or energies valued by individuals or employed as means to attain their goals [31]. Some scholars have suggested that anything perceived as valuable to an individual can be considered a resource [32].

COR theory is frequently utilized to comprehend the effects of job demands and resources on employee well-being, performance, and turnover. It offers insights into how individuals manage and safeguard their resources amidst challenges, contributing to a deeper understanding of stress, resilience, and adaptation. In the context of inclusive leadership, employees are provided with relevant work resources, facilitating the attainment of work-related goals across dimensions such as knowledge, relationships, and emotions. This provision can alleviate work pressure, mitigate physical and mental exhaustion, and enhance individual performance and well-being [33]. Moreover, inclusive leadership, characterized by attentive listening, respect, and support for employees, serves to replenish resources depleted by employees in a timely manner, bolstering their positive emotions and fostering a relaxed and secure work environment [34].

Empirical research has corroborated the significant positive impact of inclusive leadership on employees' proactivity, innovative work behavior, and willingness to voice concerns [35-37].

4. Research Content of Inclusive Leadership

The current research landscape of inclusive leadership encompasses empirically supported correlations between inclusive leadership and its antecedents, outcomes, moderators, and mediators.

4.1. Antecedents

There is a noticeable gap in empirical studies on the antecedents of inclusive leadership, pointing to a need for strategies to either foster inclusive leadership behaviors or identify leaders who naturally exhibit such traits [38].

4.2. Outcomes

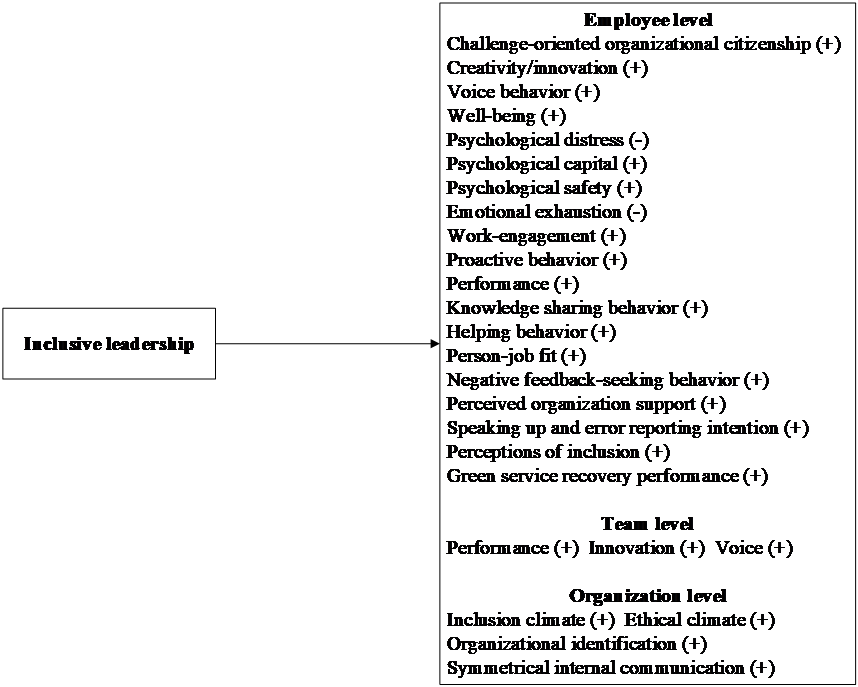

The outcomes of inclusive leadership have been widely studied, targeting the employee, team, and organizational levels (see Fig. 1). Most studies focus on the employee level, such as employee innovative behavior [3, 39] and employee psychological capital [1]. However, some studies pay attention to the team and organizational levels, such as team innovation and inclusion climate [40-41].

Figure 1: Outcomes of inclusive leadership at the employee, team, and organizational levels.

4.2.1. Employee Level

Inclusive leadership serves as a catalyst for promoting employees’ innovative behavior, emphasizing the process of innovation, which involves active participation in innovative activities rather than merely focusing on the outcome, such as the creation of new products.

Firstly, inclusive leaders cultivate an environment of psychological safety wherein employees feel comfortable expressing their ideas and perspectives without fear of judgment [37]. Through practices such as tolerating employees’ viewpoints and mistakes, attentive listening, and providing guidance and support, inclusive leaders create a conducive space for innovation to thrive. When employees perceive that their contributions are valued and respected, they are more inclined to engage in the innovation process, thereby fostering increased innovative behavior [42].

Secondly, leveraging insights from organizational support theory, inclusive leaders provide essential resources such as information, time, and support, thereby nurturing employee innovation [3]. By prioritizing employee growth and development, inclusive leaders recognize and support employees’ achievements and invest in their training. By fostering a culture of continuous learning and experimentation, inclusive leaders inspire an environment conducive to innovation.

Thirdly, inclusive leaders uphold principles of fairness and equity in their interactions with employees, ensuring that everyone has equal opportunities to contribute to and benefit from innovation efforts [1]. This fosters a collaborative and supportive environment wherein individuals are motivated to share ideas and collaborate, ultimately enhancing innovative behavior across the organization.

Inclusive leadership promotes employees’ innovative behavior. Employee innovative behavior emphasizes the process of innovation, involving active participation in innovative activities rather than solely focusing on the outcome, such as the creation of new products.

4.2.2. Team Level

Voice behavior is characterized by two fundamental attributes: discretion and riskiness [40, 43]. Consequently, the decision to engage in voice behavior is guided by two core beliefs: safety and efficacy [43-44]. Safety pertains to the belief that one’s voice will not be met with punishment, while efficacy involves the belief that one’s voice will be acknowledged and valued [40]. Inclusive leadership plays a pivotal role in shaping these beliefs by emphasizing openness, accessibility, and availability, thereby facilitating team voice.

Firstly, inclusive leaders cultivate a safe environment wherein team members feel empowered to voice their opinions without apprehension of retribution or censure [43, 45]. By fostering an atmosphere of open expression and accessibility, inclusive leaders mitigate concerns surrounding potential consequences and risks associated with voicing opinions. Moreover, by modeling openness themselves, they instill a culture of free expression among team members, further fostering voice behavior within the team [43, 45].

Secondly, inclusive leaders actively demonstrate that the input of team members is not only valued but also desired, thereby reinforcing feelings of self-worth and the obligation to voice concerns and ideas. By actively soliciting and appreciating inputs, inclusive leaders send a clear message that team voice is indispensable and respected [40, 43]. When employees perceive that their opinions are genuinely valued, they are inherently more motivated to engage in voice behavior, thereby strengthening the relationship between inclusive leadership and team voice [43].

4.2.3. Organizational Level

Inclusive leadership demonstrates a positive correlation with organizational identification, a pivotal factor in cultivating employee engagement and commitment [46]. Firstly, inclusive leaders prioritize addressing the diverse needs of their team members and actively champion their ideas and perspectives. By fostering an environment where individual contributions are valued and respected, inclusive leaders empower team members to fully immerse themselves in their work, thereby nurturing a sense of belonging and integration within the organization [46]. Moreover, inclusive leaders are perceived as embodiments of the organization’s values and policies, serving as exemplars of its identity. Their unwavering commitment to principles of fairness, diversity, and inclusion not only aligns with the organization’s overarching ethos but also sets a positive precedent for others to emulate [46]. This alignment reinforces employees’ perception of the organization as a place where their own values are mirrored and upheld.

5. Future Research Directions

When considering future research directions for inclusive leadership, several crucial considerations warrant incorporation.

5.1. Theoretical Perspective

Expanding the theoretical framework of inclusive leadership to better capture the complexities of leading diverse teams in diverse contexts represents a promising avenue for future research. While existing theories such as Conservation of Resources (COR) and Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) offer valuable insights into the mechanisms through which inclusive leadership impacts followers’ behavior, there is a need for further theoretical development concerning how inclusive leadership extends to followers and the theoretical underpinnings of inclusive leadership itself [27-30]. Scholars may explore the intersections between inclusive leadership and other leadership theories, such as transformational leadership, servant leadership, and others, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics at play.

Furthermore, additional research is warranted on the antecedents of inclusive leadership, including the influence of a leader’s personality traits. Investigating how individual differences in leaders, such as empathy, emotional intelligence, and cultural intelligence, shape their capacity for inclusive leadership can provide valuable insights into the factors that facilitate or hinder the adoption of inclusive leadership behaviors.

5.2. Research Perspective

The first is the double-edged sword effect, a concept in which an action or strategy has both positive and potentially negative consequences. In the context of inclusive leadership, future research can further explore the double-edged sword effect in inclusive leadership behavior. For example, focusing too much on the individual needs and opinions of employees can lead to less efficient decision-making or increased ambiguity about team goals. Future research could therefore seek to establish a balance that maximizes the benefits of inclusive leadership while minimizing the possible negative effects.

Secondly, the cultural difference between the East and the West is also an aspect that needs to be paid attention to in future research. Given that employees’ reactions towards leaders can vary from different cultural backgrounds, the practice of inclusive leadership may be influenced by different cultural contexts and values [47]. Hence, researchers can explore the similarities and differences in inclusive leadership behaviors in different cultural contexts and propose best practices for cross-cultural adaptation. Such cross-cultural research can promote leadership development on a global scale, enabling leaders to better adapt to diverse work environments. Although some Chinese scholars try to localize inclusive leadership and define it in the context of Chinese culture, the questionnaire in the context of Western culture is still used to measure inclusive leadership in practice, leading to inconsistencies between the definition latitude and measurement dimension, which affects the accuracy of the research.

Thirdly, as COVID-19 affects work patterns, more and more individuals are choosing to work remotely. This change presents new challenges and opportunities for inclusive leadership. Future research could focus on the effects of inclusive leadership on employee behavior and psychology in telecommuting settings. For example, research can explore how remote leaders build trust, promote team cohesion, and maintain effective communication. Additionally, the impact of remote working on employees’ job satisfaction, work-life balance, and mental health can be studied, as well as the role of inclusive leadership in these areas.

Fourthly, considering the environmental factors that influence leadership behavior and outcomes, it is necessary to study how inclusive leadership behaves differently across cultures and industries. For example, in organizations or departments with different fault tolerance types (e.g., hospitals with low fault tolerance, innovative companies with high fault tolerance), the development of inclusive leadership may be limited or promoted.

Fifthly, inclusive leadership requires more longitudinal study designs and field research [48]. Longitudinal study designs provide insight into the long-term impact of inclusive leadership on organizational culture, climate, and performance.

5.3. Application Perspective

Future research could focus on developing effective training and development programs that inform organizational practice and policy, filling the gap between theory and practice. These training programs can be designed based on the latest research findings and best practices to help leaders better understand and apply inclusive leadership concepts, thereby creating a more inclusive and diverse work environment that promotes employee development and organizational success.

Another research direction is the multiple social identities of individuals in the context of inclusive leadership. Different identities of different individuals intersect and interact with each other, shaping their experiences of privilege and marginalization [49-50]. Future research could explore how inclusive leaders navigate these intersecting identities in teams and organizations, and how they address the unique challenges faced by individuals with multiple marginalized identities.

Taken together, the future of inclusive leadership research holds great promise for our understanding of how leaders can create more inclusive, equitable, and efficient organizations. Through these three perspectives, scholars can contribute to the theoretical and practical development of inclusive leadership, enabling leaders to embrace diversity and foster an inclusive culture, both inside and outside the workplace.

6. Conclusion

This paper addresses four main areas in response to the burgeoning interest and surge in research on inclusive leadership. Firstly, it delves into how scholars in the literature comprehend, define, and measure inclusive leadership. Secondly, it reviews the theories pertinent to inclusive leadership. Thirdly, it highlights the outcome variables associated with inclusive leadership. Lastly, drawing from current research developments, it outlines potential directions for future research aimed at advancing scholars’ understanding and practice of inclusive leadership in the field.

The review underscores that inclusive leadership has emerged as a pivotal concept in organizational research, accentuating the significance of leaders fostering environments that value diverse perspectives and inclusively respect all individuals. In navigating an increasingly interconnected and diverse global landscape, the trajectory of inclusive leadership studies holds immense significance.

References

[1]. Fang, Y. C., Chen, J. Y., Wang, M. J., & Chen, C. Y. (2019). The impact of inclusive leadership on employees’ innovative behaviors: the mediation of psychological capital. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1803.

[2]. Schroth, H. (2019). Are you ready for Gen Z in the workplace?. California Management Review, 61(3), 5-18.

[3]. Qi, L., Liu, B., Wei, X., & Hu, Y. (2019). Impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior: Perceived organizational support as a mediator. PloS One, 14(2), e0212091.

[4]. Zhang, S., Liu, Y., Li, G., Zhang, Z., & Fa, T. (2022). Chinese nurses’ innovation capacity: The influence of inclusive leadership, empowering leadership and psychological empowerment. Journal of Nursing Management, 30(6), 1990-1999.

[5]. Chen, L., Luo, F., Zhu, X., Huang, X., & Liu, Y. (2020). Inclusive leadership promotes challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behavior through the mediation of work engagement and moderation of organizational innovative atmosphere. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 560594.

[6]. Choi, S. B., Tran, T. B. H., & Kang, S. W. (2017). Inclusive leadership and employee well-being: The mediating role of person-job fit. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18, 1877-1901.

[7]. Strom, D. L., Sears, K. L., & Kelly, K. M. (2014). Work engagement: The roles of organizational justice and leadership style in predicting engagement among employees. Journal of leadership & organizational studies, 21(1), 71-82.

[8]. Meng, Q., & Sun, F. (2019). The impact of psychological empowerment on work engagement among university faculty members in China. Psychology research and behavior management, 983-990.

[9]. Al-Atwi, A. A., & Al-Hassani, K. K. (2021). Inclusive leadership: Scale validation and potential consequences. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(8), 1222-1240.

[10]. Nembhard, I. M., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 27(7), 941-966.

[11]. Hollander, E. P. (2009). Inclusive leadership : The essential leader-follower relationship. New York : Routledge. https://find.library.duke.edu/catalog/DUKE004928389

[12]. Nishii, L. H., & Mayer, D. M. (2009). Do inclusive leaders help to reduce turnover in diverse groups? The moderating role of leader–member exchange in the diversity to turnover relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1412.

[13]. Carmeli, A., Reiter-Palmon, R., & Ziv, E. (2010). Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creativity Research Journal, 22(3), 250-260.

[14]. Randel, A. E., Galvin, B. M., Shore, L. M., Ehrhart, K. H., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., & Kedharnath, U. (2018). Inclusive leadership: Realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Human Resource Management Review, 28(2), 190-203.

[15]. Tang, N., & Zhang, K. L. (2015). Inclusive leadership: Review and prospects. China Journaal Management, 12, 932-938.

[16]. Yao, M. H., & Li, Y. X. (2014). Study on mechanism of inclusive leadership and employee innovation behaviors. Science and Technology Progress and Countermeasures, 31, 6-9.

[17]. Fang, Y. C., & Jin, H. H. (2014). Empirical study on impact of inclusive leadership on performance of scientific research team in university. Technology Economic, 33, 53-57.

[18]. Zhu, Y., & Qian, S. T. (2014). Analysis of the frontier of inclusive leadership research and future prospects. Foreign Economis Management, 36, 55-80.

[19]. Li, Y. P., Yang, T., Pan, Y. J., & Xu, J. (2012). Construction and implementation of inclusive leadership: From the perspective of new generation employees management. Human Resource Development in China, (3), 31-35.

[20]. House, R. J., & Mitchell, T. R. (1975). Path goal theory of leadership (pp. 75-67). Faculty of Management Studies, University of Toronto.

[21]. Cunliffe, A. L., & Eriksen, M. (2011). Relational leadership. Human Relations, 64(11), 1425-1449.

[22]. Dong, L. B., & Feng, Z. J. (2014). Relational Leadership theory and its application in educational management. Educational Theory and Practice, (7), 17-20.

[23]. Hirak, R., Peng, A. C., Carmeli, A., & Schaubroeck, J. M. (2012). Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: The importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(1), 107-117.

[24]. Dong, X. H. (2000). A preliminary study on the thought of flexible management. East China Economic Management, 14(1), 14-15.

[25]. Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219-247.

[26]. Liden, R. C., Sparrowe, R. T., & Wayne, S. J. (1997). Leader-member exchange theory: The past and potential for the future.

[27]. Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1991). The transformation of professionals into self-managing and partially self-designing contributors: Toward a theory of leadership-making.

[28]. Herman, H. M., Huang, X., & Lam, W. (2013). Why does transformational leadership matter for employee turnover? A multi-foci social exchange perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(5), 763-776.

[29]. Volmer, J., Spurk, D., & Niessen, C. (2012). Leader–member exchange (LMX), job autonomy, and creative work involvement. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(3), 456-465.

[30]. Hobfoll, S. E., & Lilly, R. S. (1993). Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology, 21(2), 128-148.

[31]. Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513.

[32]. Gorgievski, M. J., Halbesleben, J. R., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). Expanding the boundaries of psychological resource theories. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 1-7.

[33]. Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499.

[34]. Zhao, F., Ahmed, F., & Faraz, N. A. (2020). Caring for the caregiver during COVID-19 outbreak: Does inclusive leadership improve psychological safety and curb psychological distress? A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 110, 103725.

[35]. Javed, B., Fatima, T., Khan, A. K., & Bashir, S. (2021). Impact of inclusive leadership on innovative work behavior: The role of creative self‐efficacy. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 55(3), 769-782.

[36]. Jolly, P. M., & Lee, L. (2021). Silence is not golden: Motivating employee voice through inclusive leadership. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 45(6), 1092-1113.

[37]. Lee, S. E., & Dahinten, V. S. (2021). Psychological safety as a mediator of the relationship between inclusive leadership and nurse voice behaviors and error reporting. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 53(6), 737-745.

[38]. Korkmaz, A. V., Van Engen, M. L., Knappert, L., & Schalk, R. (2022). About and beyond leading uniqueness and belongingness: A systematic review of inclusive leadership research. Human Resource Management Review, 32(4), 100894.

[39]. Wang, H., Chen, M., & Li, X. (2021). Moderating multiple mediation model of the impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 666477.

[40]. Ye, Q., Wang, D., & Guo, W. (2019). Inclusive leadership and team innovation: The role of team voice and performance pressure. European Management Journal, 37(4), 468-480.

[41]. Ashikali, T., Groeneveld, S., & Kuipers, B. (2021). The role of inclusive leadership in supporting an inclusive climate in diverse public sector teams. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 41(3), 497-519.

[42]. Zhu, J., Xu, S., & Zhang, B. (2020). The paradoxical effect of inclusive leadership on subordinates’ creativity. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 2960.

[43]. Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open?. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869-884.

[44]. Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373-412.

[45]. Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1419-1452.

[46]. Song, J., Wang, D., & He, C. (2023). Why and when does inclusive leadership evoke employee negative feedback-seeking behavior?. European Management Journal, 41(2), 292-301.

[47]. Song, J., Wang, D., & He, C. (2023). Why and when does inclusive leadership evoke employee negative feedback-seeking behavior?. European Management Journal, 41(2), 292-301.

[48]. Ahmed, F., Zhao, F., Faraz, N. A., & Qin, Y. J. (2021). How inclusive leadership paves way for psychological well‐being of employees during trauma and crisis: A three‐wave longitudinal mediation study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(2), 819-831.

[49]. Shore, L. M., & Chung, B. G. (2022). Inclusive leadership: How leaders sustain or discourage work group inclusion. Group & Organization Management, 47(4), 723-754.

[50]. Glass, C., & Cook, A. (2020). Performative contortions: How White women and people of colour navigate elite leadership roles. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(6), 1232-1252.

Cite this article

Liu,Z. (2024). A Review and Prospect of Research on Inclusive Leadership. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,58,63-73.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Education Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Fang, Y. C., Chen, J. Y., Wang, M. J., & Chen, C. Y. (2019). The impact of inclusive leadership on employees’ innovative behaviors: the mediation of psychological capital. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1803.

[2]. Schroth, H. (2019). Are you ready for Gen Z in the workplace?. California Management Review, 61(3), 5-18.

[3]. Qi, L., Liu, B., Wei, X., & Hu, Y. (2019). Impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior: Perceived organizational support as a mediator. PloS One, 14(2), e0212091.

[4]. Zhang, S., Liu, Y., Li, G., Zhang, Z., & Fa, T. (2022). Chinese nurses’ innovation capacity: The influence of inclusive leadership, empowering leadership and psychological empowerment. Journal of Nursing Management, 30(6), 1990-1999.

[5]. Chen, L., Luo, F., Zhu, X., Huang, X., & Liu, Y. (2020). Inclusive leadership promotes challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behavior through the mediation of work engagement and moderation of organizational innovative atmosphere. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 560594.

[6]. Choi, S. B., Tran, T. B. H., & Kang, S. W. (2017). Inclusive leadership and employee well-being: The mediating role of person-job fit. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18, 1877-1901.

[7]. Strom, D. L., Sears, K. L., & Kelly, K. M. (2014). Work engagement: The roles of organizational justice and leadership style in predicting engagement among employees. Journal of leadership & organizational studies, 21(1), 71-82.

[8]. Meng, Q., & Sun, F. (2019). The impact of psychological empowerment on work engagement among university faculty members in China. Psychology research and behavior management, 983-990.

[9]. Al-Atwi, A. A., & Al-Hassani, K. K. (2021). Inclusive leadership: Scale validation and potential consequences. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(8), 1222-1240.

[10]. Nembhard, I. M., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 27(7), 941-966.

[11]. Hollander, E. P. (2009). Inclusive leadership : The essential leader-follower relationship. New York : Routledge. https://find.library.duke.edu/catalog/DUKE004928389

[12]. Nishii, L. H., & Mayer, D. M. (2009). Do inclusive leaders help to reduce turnover in diverse groups? The moderating role of leader–member exchange in the diversity to turnover relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1412.

[13]. Carmeli, A., Reiter-Palmon, R., & Ziv, E. (2010). Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creativity Research Journal, 22(3), 250-260.

[14]. Randel, A. E., Galvin, B. M., Shore, L. M., Ehrhart, K. H., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., & Kedharnath, U. (2018). Inclusive leadership: Realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Human Resource Management Review, 28(2), 190-203.

[15]. Tang, N., & Zhang, K. L. (2015). Inclusive leadership: Review and prospects. China Journaal Management, 12, 932-938.

[16]. Yao, M. H., & Li, Y. X. (2014). Study on mechanism of inclusive leadership and employee innovation behaviors. Science and Technology Progress and Countermeasures, 31, 6-9.

[17]. Fang, Y. C., & Jin, H. H. (2014). Empirical study on impact of inclusive leadership on performance of scientific research team in university. Technology Economic, 33, 53-57.

[18]. Zhu, Y., & Qian, S. T. (2014). Analysis of the frontier of inclusive leadership research and future prospects. Foreign Economis Management, 36, 55-80.

[19]. Li, Y. P., Yang, T., Pan, Y. J., & Xu, J. (2012). Construction and implementation of inclusive leadership: From the perspective of new generation employees management. Human Resource Development in China, (3), 31-35.

[20]. House, R. J., & Mitchell, T. R. (1975). Path goal theory of leadership (pp. 75-67). Faculty of Management Studies, University of Toronto.

[21]. Cunliffe, A. L., & Eriksen, M. (2011). Relational leadership. Human Relations, 64(11), 1425-1449.

[22]. Dong, L. B., & Feng, Z. J. (2014). Relational Leadership theory and its application in educational management. Educational Theory and Practice, (7), 17-20.

[23]. Hirak, R., Peng, A. C., Carmeli, A., & Schaubroeck, J. M. (2012). Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: The importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(1), 107-117.

[24]. Dong, X. H. (2000). A preliminary study on the thought of flexible management. East China Economic Management, 14(1), 14-15.

[25]. Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219-247.

[26]. Liden, R. C., Sparrowe, R. T., & Wayne, S. J. (1997). Leader-member exchange theory: The past and potential for the future.

[27]. Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1991). The transformation of professionals into self-managing and partially self-designing contributors: Toward a theory of leadership-making.

[28]. Herman, H. M., Huang, X., & Lam, W. (2013). Why does transformational leadership matter for employee turnover? A multi-foci social exchange perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(5), 763-776.

[29]. Volmer, J., Spurk, D., & Niessen, C. (2012). Leader–member exchange (LMX), job autonomy, and creative work involvement. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(3), 456-465.

[30]. Hobfoll, S. E., & Lilly, R. S. (1993). Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology, 21(2), 128-148.

[31]. Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513.

[32]. Gorgievski, M. J., Halbesleben, J. R., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). Expanding the boundaries of psychological resource theories. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 1-7.

[33]. Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499.

[34]. Zhao, F., Ahmed, F., & Faraz, N. A. (2020). Caring for the caregiver during COVID-19 outbreak: Does inclusive leadership improve psychological safety and curb psychological distress? A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 110, 103725.

[35]. Javed, B., Fatima, T., Khan, A. K., & Bashir, S. (2021). Impact of inclusive leadership on innovative work behavior: The role of creative self‐efficacy. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 55(3), 769-782.

[36]. Jolly, P. M., & Lee, L. (2021). Silence is not golden: Motivating employee voice through inclusive leadership. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 45(6), 1092-1113.

[37]. Lee, S. E., & Dahinten, V. S. (2021). Psychological safety as a mediator of the relationship between inclusive leadership and nurse voice behaviors and error reporting. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 53(6), 737-745.

[38]. Korkmaz, A. V., Van Engen, M. L., Knappert, L., & Schalk, R. (2022). About and beyond leading uniqueness and belongingness: A systematic review of inclusive leadership research. Human Resource Management Review, 32(4), 100894.

[39]. Wang, H., Chen, M., & Li, X. (2021). Moderating multiple mediation model of the impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 666477.

[40]. Ye, Q., Wang, D., & Guo, W. (2019). Inclusive leadership and team innovation: The role of team voice and performance pressure. European Management Journal, 37(4), 468-480.

[41]. Ashikali, T., Groeneveld, S., & Kuipers, B. (2021). The role of inclusive leadership in supporting an inclusive climate in diverse public sector teams. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 41(3), 497-519.

[42]. Zhu, J., Xu, S., & Zhang, B. (2020). The paradoxical effect of inclusive leadership on subordinates’ creativity. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 2960.

[43]. Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open?. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869-884.

[44]. Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373-412.

[45]. Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1419-1452.

[46]. Song, J., Wang, D., & He, C. (2023). Why and when does inclusive leadership evoke employee negative feedback-seeking behavior?. European Management Journal, 41(2), 292-301.

[47]. Song, J., Wang, D., & He, C. (2023). Why and when does inclusive leadership evoke employee negative feedback-seeking behavior?. European Management Journal, 41(2), 292-301.

[48]. Ahmed, F., Zhao, F., Faraz, N. A., & Qin, Y. J. (2021). How inclusive leadership paves way for psychological well‐being of employees during trauma and crisis: A three‐wave longitudinal mediation study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(2), 819-831.

[49]. Shore, L. M., & Chung, B. G. (2022). Inclusive leadership: How leaders sustain or discourage work group inclusion. Group & Organization Management, 47(4), 723-754.

[50]. Glass, C., & Cook, A. (2020). Performative contortions: How White women and people of colour navigate elite leadership roles. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(6), 1232-1252.