1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Adolescence is a path for everyone to become mature and it is also the most significant period for teenagers to have contact with society .Young people began to gradually have their own subjective thoughts and opportunities to communicate with people who are not familiar with them before [1]. However, during social contact ,interpersonal relationship has become a major problem for many teenagers due to several factors. Many young people cannot take the initiative to establish some good interpersonal relationships [2].social anxiety disorder [3]seems a typical negative reflaction of interpersonal relationship .that can be influenced by growing environment,actually the family [4].SAD will brings influence on adolescents’ socialization. At the same time, as teenagers spend more time in school, interacting with peers is a new type of social interaction. When peers e get along with each other, many problems may arise due to differences in thinking or personality [2].

Gradually, under the influence of the long-term family environment and peer interaction patterns, some teenagers have a series of mental health problems. Including social phobia, low self -esteem, teenage depression etc.[5].

In this article an in-depth analysis of the influence of family and school on the social interaction of adolescents is conducted , and at the same time the process of mental health problems is discussed .

1.2. Parent-child relationships

From the current research results and theories, parent-child relationship has undoubtedly the greatest impact on the development of adolescents [6]. In general, there are four models from previous empirical researches that were used for describing different patterns of how friendships may moderate the association between parent-adolescent relationships and adolescent emotional functioning : 1) the reinforcement model, 2) the toxic friends model, 3) the compensation model, and 4) the additive model. The quality of the relationship between adolescents and parents was assessed with two subscales of the Network of Relationships Inventory: satisfaction and conflict [7]. Open and inclusive family relationships can not only enable children to gain more self-confidence and self-affirmation, but also subtly reduce teenagers' social anxiety, and more conducive to cultivating their ability to regulate emotions and independent thinking [8]. Based on the past experiments and researches, scientists found that if parent reported higher levels of positive problem solving and conflict engagement towards their children than adolescents, whereas the youth reported significantly higher levels of withdrawal towards their parents than the adults [9]. Nowadays, in the fast-paced life state, the increasing lack of work pressure makes it hard for many parents to balance work and life, and therefore miss the important stage of their children's growth. Meanwhile, parents who under high stressed life and engage in parenting practices frequently can have negative effects on children (e.g., authoritarian parenting, overprotection and higher child neglect and abuse potential) [10]. There are many practical reasons that make conflict and confrontation in parent-child relationship become more common than concern and love. For instance, during the lockdown of COVID-19, it is reported that in comparison to the period before, child emotional neglect was three times higher [11]. One of the risk factors of this problem when the pandemic broke out could be parental burnout, which is defined as “a state of intense exhaustion related to one’s parental role, in which one becomes emotionally detached from one’s children and doubtful of one’s capacity to be a good parent” [12][13]. In the family, every move of parents will be seen and even imitated by children, especially for younger children, observing their parents' behavior is the most common way they learn to interact with the world. The unhealthy family relationships will indirectly affect the way and attitude of teenagers towards interpersonal relationships, so that they can not maintain a positive attitude when they get along with their peers. The different growth environment and life experience of parents and teenagers will also lead to communication difficulties in parent-child relationship and the situation that both parties cannot communicate effectively.

1.3. Relationships among peers

In addition to the parent-child relationship in the family environment, school is another important place for teenagers to socialize, so that the interpersonal relationships between students also have an important impact on teenagers' health behavior choices, academic performance, spiritual world construction and mental health [14]. Normally, familiar adults such as parents and teachers are recognized as a certain sense of security for adolescents, but peers, in particularly, make students’ time at school more and more enjoyable. With the increase of time with schoolmates and the maturity of adolescent minds, the status in peer social networks will have a more significant impact on students [2]. Good relationships with peers can help teens deal with setbacks in a more positive way, give them more opportunities to talk to when they are down, and improve their ability of self-healing and relieving stress. As the progress of technology, the social ways of high school students also tend to be diversified, the amount of screen time that spent on socializing is rising quickly, these teenagers might get many kinds of feedback when they are spending time with peers or browsing the social media, some people can gain more strength in the process of being familiar with others, while someone may lose confidence and affect their self-esteem by comparing themselves with others. A number of studies have shown that the increase in the use of electronic products can increase the probability of depression, self-harm and even suicide [15]. Meanwhile, longitudinal studies have also illustrated that low levels of self-esteem have been linked with delinquency, substance abuse, depression, anger, and aggression [16]. Since adolescence is as well as a developmental period characterized by the desire to “fit in” with peers although they may from different growth settings and family systems. Previous study had shown that having supportive friendships, feeling liked by others, and playing or socializing with others may be important protective factors for depression [17]. The quality of friendships between teenagers and their close friends is also correlated with the number of friends they have. A cross-sectional mediation analysis had demonstrated that singles were more invested in their friendships than partnered people, whereas greater friendship investment predicted better friendship quality and self-esteem over time [18].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

The target population comprised 119 high school students in Sichuan province who were at the range of 15-18 years old, all of them are native Chinese speakers. Chinese students of this age normally have a large amount of schoolwork pressure, whether they are studying in a boarding or day school, which makes their social life and interpersonal relationships usually divided into two parts of school and family. The questionnaire will be distributed through the Internet, and participants will fill out anonymously. It will take 8-10 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

2.2. Measures

A ten-question questionnaire is designed for this study, which was written in Chinese considering that all participants were native speakers of Chinese. The first three questions are presented in the form of a scale with 1-5 different levels, which is mainly used to investigate the general state of the relationship between the participating students and their parents. Scientists had indicated that the low levels of parental knowledge and high levels of both parental support and parent-adolescent conflict were associated with the antisocial behaviors through increasing the affiliation with an antisocial peer group [19].

Therefore, in the first question, participants were asked to rate how demanding and intrusive their parents were in their social experiences, with level 1 being none at all and level 5 being mandatory. The next two questions will evaluate the degree of closeness and support of parent-adolescent relationship. In order to make the question expression more specific, some descriptions are added to the scale content of the second question (level 1 is not at all, no communication; level 5 is very intimate, talk about everything).

Question 4 and 5 use the same scenario for parent-child relationship and peer relationship. When the two parties in a relationship have different opinions, what kind of means will participants choose to resolve the conflict and avoid the fierce conflict is the focus of investigation. These two questions are single choice, with five options from A to E, A. Actively communicate and find the most suitable ways; B. Expect the other person to actively communicate with them (more passive); C. Always stick to their own ideas; D. Completely compromise other people’s points; E. Others.

After that, participants can select how many close friends do they have in question 6, there are four choices range from 0, 1~3, 3~5 and 5 or even more. The next two scale questions assessed participants' attitudes toward friendship, such as whether they were willing to actively maintain a relationship and whether they often worried that a relationship would be unstable or have adverse consequences (with level 1 totally disagree, level 5 totally agree). Two remaining single choice questions are used for collecting their gender (female, male or other) and age (15, 16, 17 or 18).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives and correlations

The gender and age of all the participants in the current study are shown in Table 1. In total, 119 results of this questionnaire have been collected, which illustrates that more than 69.7% came from female participants and the remain part includes 26.9 from male and 3.4% from other gender. For age range, forty-three of the 119 were 16 years old, there was only one difference between the number of 15 - and 18-year-olds, 28 and 29 respectively.

Table 1: The gender and age distribution of participants were analyzed

Sex | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | |

Valid | female | 83 | 69.7 | 69.7 | 69.7 |

male | 32 | 26.9 | 26.9 | 96.6 | |

other | 4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 100.0 | |

Total | 119 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Age | |||||

Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

Valid | 15 | 28 | 23.5 | 23.5 | 23.5 |

16 | 43 | 36.1 | 36.1 | 59.7 | |

17 | 19 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 75.6 | |

18 | 29 | 24.4 | 24.4 | 100.0 | |

Total | 119 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

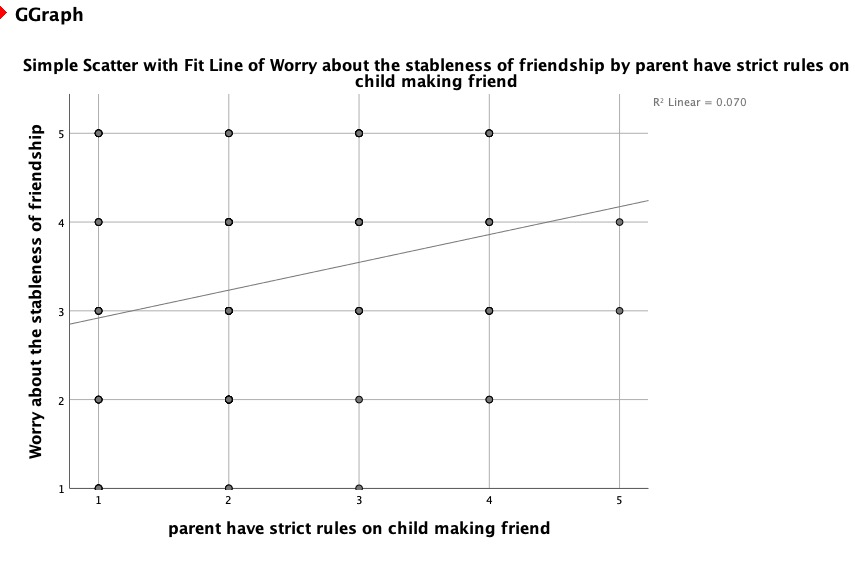

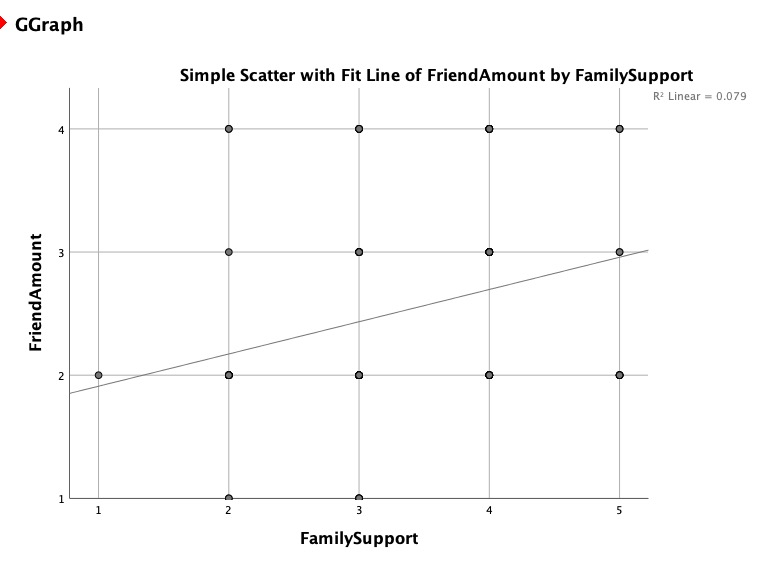

Correlations between parent have strict rules on child making friends and worry about the stableness of friendships are presented in Table 2, there was a positive correlation between these two factors, r(117)=.264 , p=.004<.05. Generally,it seems that adolescents’ misgivings about the uncertainties of friendship are significantly related to the degree of parental interference in their friendships (see Figure 1). The positive trend was also exist when the correlation between the amount of friends and the extent of family support were investigated. r(117)=.282 , p=.002<.05 (Table 4), and the simple scatter with fit line of this result is shown in Figure 2. Table 3 and table 4 illustrate the frequencies of different methods that the participants chose from when they had conflicts with parents or friends, five options were provided for them—active communication, passive communication, insist on personal opinion, change self to please others and other ways. It is obvious to see that more than 71 students prefer to communicate with their friends actively, by contrast, the number of people who choose the same way in another situation is fewer—just 45. Also, according to the results of the questionnaire, participants are more likely to stick to their own opinions rather than compromise with their family members when they have different opinions. Table 5 reports ANOVA results which indicates the mean square of friend amount is 2.236.

Table 2: The correlation between parental strictness in making friends and participants' concerns about friendship

Parent have strict rules on child making friend | Worry about the stableness of friendship | ||

Parent have strict rules on child making friend | Pearson correlation | 1 | .264** |

Sig. (2-tailed) | .004 | ||

N | 119 | 119 | |

Worry about the stableness of friendship | Pearson correlation | .264** | 1 |

Sig. (2-tailed) | .004 | ||

N | 119 | 119 | |

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). | |||

Figure 1: Simple Scatter with Fit Line of Worry about thr stableness of friendship by paren have strict rules on child making friend

Table 3: The correlations between friend amount and family support

Friend Amount | Family Support | ||

Friend amount | Pearson correlation | 1 | .282** |

Sig. (2-tailed) | .002 | ||

N | 119 | 119 | |

Family support | Pearson correlation | .282** | 1 |

Sig. (2-tailed) | .002 | ||

N | 119 | 119 | |

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). | |||

Table 4: The different ways participants resolve conflicts with family and friends

Family Conflict | |||||

Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

Valid | Active communication | 45 | 37.8 | 37.8 | 37.8 |

Passive communication | 28 | 23.5 | 23.5 | 61.3 | |

Insist on personal opinion | 25 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 82.4 | |

Change self to please others | 5 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 86.6 | |

Others | 16 | 13.4 | 13.4 | 100.0 | |

Total | 119 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Friend Conflict | |||||

Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

Valid | Active communication | 71 | 59.7 | 59.7 | 59.7 |

Passive communication | 24 | 20.2 | 20.2 | 79.8 | |

Insist on personal opinion | 8 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 86.6 | |

Change self to please others | 7 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 92.4 | |

Others | 9 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 100.0 | |

Total | 119 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Figure 2: Simple Scatter with Fit Line of FriendAmount by FamilySupport

Table 5: Report anova results (oneway FriendAmount BY FamilySupport)

FriendAmount | |||||

Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Sig. | |

Between Groups | 8.939 | 4 | 2.235 | 3.507 | .010 |

Within Groups | 72.641 | 114 | .637 | ||

Total | 81.580 | 118 | |||

4. Discussion

In this study,it shows that family and peers do have a significant impact on adolescents' interpersonal interactions. The research shows that the way that families control and manage adolescents' interpersonal interactions will directly affect the number of friends they make and their cognitive judgments in this aspect. Before the investigation, we predicted the connection between family management and adolescent interpersonal relationship based on some actual situations. After the investigation,the conjecture was confirmed. The data graph clearly and intuitively reflects the positive trend between family constraints and support levels and the number of friends teenagers make and their judgment in making friends. The research shows that beyond higher levels of family control and lower levels of parental support teenagers will show more lack of confidence in friendships and have few friends when in friends -making. In addition, the people we surveyed also showed different attitudes towards family and peers in terms of how they deal with problems which they encounter in relationships. Regarding family, most respondents prefer to have good and positive communication with their peers, but they will be more insistent on their own ideas when facing family. This study explores the factors that affect adolescents’ interpersonal interactions. The survey data can confirm and support that our initial guess is reasonable. However, the report also has significant limitations. First of all, the sample size is very small, only more than 100 pieces of data, and the exploration dimension is limited to a small number of daily problems so this means that the data results are not representative of teenagers in China or the world. Second, all information is based on researchers’s subjective thoughts which may result a certain bias in what is stated. Third, the views that the researchers state may not take into account some other academic discussions on this aspect. In view of the above limitations, researchers need further research to improve.

5. Conclusion

This study sets out to find the factors that effect adolecents’ interpersonal interactions. According to this study, the researchers wants people to pay more attention to the interpersonal communication and mental health of adolescents.To make the results more scientific, the researchers use survey that is made by seven daily questions to collect the data. However, the report also has significant limitations. First of all, the sample size is very small, so this means that the data results are not representative of teenagers in China or the world. Second, all information is based on researchers’s subjective thoughts which may result a certain bias in what is stated. Third, the views that the researchers state may not take into account some other academic discussions on this aspect. In future study researchers can have in-depth exploration in the following aspects. First, collecting larger samples can be used to enhance the reliability and generalization ability of the research results. Secondly, more advanced methods and technologies can be applied to collect and analyze data more comprehensively and accurately. Finally, the results of this study can be compared and verified with other related studies to further confirm the validity and reliability of the conclusions.

In conclusion , it is hoped that these research results can have a positive impact on the development of related fields and the progress of society. Also thanks to everyone who contributed to this study.

Acknowledgement

Yuqi Wu and Yuzhe Xia contributed equally to this work and should be considered as co-first authors.

References

[1]. Kenny, R., Dooley, B., & Fitzgerald, A. (2013). Interpersonal relationships and emotional distress in adolescence. Journal of adolescence, 36(2), 351-360.

[2]. Kiuru, N., Wang, M. T., Salmela-Aro, K., Kannas, L., Ahonen, T., & Hirvonen, R. (2020). Associations between adolescents’ interpersonal relationships, school well-being, and academic achievement during educational transitions. Journal of youth and adolescence, 49, 1057-1072.

[3]. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Social Anxiety Disorder: Recognition, Assessment and Treatment. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society (UK); 2013. (NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 159.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK266258/

[4]. Ahmadzadeh, Y. I., Eley, T. C., Leve, L. D., Shaw, D. S., Natsuaki, M. N., Reiss, D., ... & McAdams, T. A. (2019). Anxiety in the family: A genetically informed analysis of transactional associations between mother, father and child anxiety symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(12), 1269-1277.

[5]. O’Day, E. B., & Heimberg, R. G. (2021). Social media use, social anxiety, and loneliness: A systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 3, 100070.

[6]. Boucher, M. È., Pugliese, J., Allard‐Chapais, C., Lecours, S., Ahoundova, L., Chouinard, R., & Gaham, S. (2017). Parent–child relationship associated with the development of borderline personality disorder: a systematic review. Personality and Mental Health, 11(4), 229-255.

[7]. Huang, L., Huang, X., Wang, J., Zhang, F., Fei, Y., Tang, J., & Wang, Y. (2023). Factors influencing parent-child relationships in chinese nurses: a cross-sectional study. BMC nursing, 22(1), 1-10.

[8]. Ratliff, E. L., Morris, A. S., Cui, L., Jespersen, J. E., Silk, J. S., & Criss, M. M. (2023). Supportive parent-adolescent relationships as a foundation for adolescent emotion regulation and adjustment. Frontiers in Psychology, 14.

[9]. Van Doorn, M. D., Branje, S. J., & Meeus, W. H. (2011). Developmental changes in conflict resolution styles in parent–adolescent relationships: A four-wave longitudinal study. Journal of youth and adolescence, 40, 97-107.

[10]. Farley, R., de Diaz, N. A. N., Emerson, L. M., Simcock, G., Donovan, C., & Farrell, L. J. (2023). Mindful Parenting Group Intervention for Parents of Children with Anxiety Disorders. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 1-12.

[11]. Vermeulen, S., Alink, L. R., & van Berkel, S. R. (2023). Child maltreatment during school and childcare closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Child maltreatment, 28(1), 13-23.

[12]. Mikolajczak, M., Brianda, M. E., Avalosse, H., & Roskam, I. (2018). Consequences of parental burnout: Its specific effect on child neglect and violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 134–145.

[13]. Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., & Roskam, I. (2019). Parental Burnout: What Is It, and Why Does It Matter? Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1319–1329.

[14]. Hanafin, J., Sunday, S., & Clancy, L. (2021). Friends and family matter Most: a trend analysis of increasing e-cigarette use among Irish teenagers and socio-demographic, personal, peer and familial associations. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1-12.

[15]. De Vries, D. A., Peter, J., De Graaf, H., & Nikken, P. (2016). Adolescents’ social network site use, peer appearance-related feedback, and body dissatisfaction: Testing a mediation model. Journal of youth and adolescence, 45, 211-224.

[16]. Keizer, R., Helmerhorst, K. O., & van Rijn-van Gelderen, L. (2019). Perceived quality of the mother–adolescent and father–adolescent attachment relationship and adolescents’ self-esteem. Journal of youth and adolescence, 48(6), 1203-1217.

[17]. Powell, V., Riglin, L., Hammerton, G., Eyre, O., Martin, J., Anney, R., ... & Rice, F. (2020). What explains the link between childhood ADHD and adolescent depression? Investigating the role of peer relationships and academic attainment. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 29, 1581-1591.

[18]. Fisher, A. N., Stinson, D. A., Wood, J. V., Holmes, J. G., & Cameron, J. J. (2021). Singlehood and attunement of self-esteem to friendships. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(7), 1326-1334.

[19]. Cutrín, O., Gómez-Fraguela, J. A., Maneiro, L., & Sobral, J. (2017). Effects of parenting practices through deviant peers on nonviolent and violent antisocial behaviours in middle-and late-adolescence. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 9(2), 75-82.

Cite this article

Wu,Y.;Xia,Y. (2024). A Study of Interpersonal Relationships and Mental Health in Adolescence. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,60,34-41.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Kenny, R., Dooley, B., & Fitzgerald, A. (2013). Interpersonal relationships and emotional distress in adolescence. Journal of adolescence, 36(2), 351-360.

[2]. Kiuru, N., Wang, M. T., Salmela-Aro, K., Kannas, L., Ahonen, T., & Hirvonen, R. (2020). Associations between adolescents’ interpersonal relationships, school well-being, and academic achievement during educational transitions. Journal of youth and adolescence, 49, 1057-1072.

[3]. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Social Anxiety Disorder: Recognition, Assessment and Treatment. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society (UK); 2013. (NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 159.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK266258/

[4]. Ahmadzadeh, Y. I., Eley, T. C., Leve, L. D., Shaw, D. S., Natsuaki, M. N., Reiss, D., ... & McAdams, T. A. (2019). Anxiety in the family: A genetically informed analysis of transactional associations between mother, father and child anxiety symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(12), 1269-1277.

[5]. O’Day, E. B., & Heimberg, R. G. (2021). Social media use, social anxiety, and loneliness: A systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 3, 100070.

[6]. Boucher, M. È., Pugliese, J., Allard‐Chapais, C., Lecours, S., Ahoundova, L., Chouinard, R., & Gaham, S. (2017). Parent–child relationship associated with the development of borderline personality disorder: a systematic review. Personality and Mental Health, 11(4), 229-255.

[7]. Huang, L., Huang, X., Wang, J., Zhang, F., Fei, Y., Tang, J., & Wang, Y. (2023). Factors influencing parent-child relationships in chinese nurses: a cross-sectional study. BMC nursing, 22(1), 1-10.

[8]. Ratliff, E. L., Morris, A. S., Cui, L., Jespersen, J. E., Silk, J. S., & Criss, M. M. (2023). Supportive parent-adolescent relationships as a foundation for adolescent emotion regulation and adjustment. Frontiers in Psychology, 14.

[9]. Van Doorn, M. D., Branje, S. J., & Meeus, W. H. (2011). Developmental changes in conflict resolution styles in parent–adolescent relationships: A four-wave longitudinal study. Journal of youth and adolescence, 40, 97-107.

[10]. Farley, R., de Diaz, N. A. N., Emerson, L. M., Simcock, G., Donovan, C., & Farrell, L. J. (2023). Mindful Parenting Group Intervention for Parents of Children with Anxiety Disorders. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 1-12.

[11]. Vermeulen, S., Alink, L. R., & van Berkel, S. R. (2023). Child maltreatment during school and childcare closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Child maltreatment, 28(1), 13-23.

[12]. Mikolajczak, M., Brianda, M. E., Avalosse, H., & Roskam, I. (2018). Consequences of parental burnout: Its specific effect on child neglect and violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 134–145.

[13]. Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., & Roskam, I. (2019). Parental Burnout: What Is It, and Why Does It Matter? Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1319–1329.

[14]. Hanafin, J., Sunday, S., & Clancy, L. (2021). Friends and family matter Most: a trend analysis of increasing e-cigarette use among Irish teenagers and socio-demographic, personal, peer and familial associations. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1-12.

[15]. De Vries, D. A., Peter, J., De Graaf, H., & Nikken, P. (2016). Adolescents’ social network site use, peer appearance-related feedback, and body dissatisfaction: Testing a mediation model. Journal of youth and adolescence, 45, 211-224.

[16]. Keizer, R., Helmerhorst, K. O., & van Rijn-van Gelderen, L. (2019). Perceived quality of the mother–adolescent and father–adolescent attachment relationship and adolescents’ self-esteem. Journal of youth and adolescence, 48(6), 1203-1217.

[17]. Powell, V., Riglin, L., Hammerton, G., Eyre, O., Martin, J., Anney, R., ... & Rice, F. (2020). What explains the link between childhood ADHD and adolescent depression? Investigating the role of peer relationships and academic attainment. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 29, 1581-1591.

[18]. Fisher, A. N., Stinson, D. A., Wood, J. V., Holmes, J. G., & Cameron, J. J. (2021). Singlehood and attunement of self-esteem to friendships. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(7), 1326-1334.

[19]. Cutrín, O., Gómez-Fraguela, J. A., Maneiro, L., & Sobral, J. (2017). Effects of parenting practices through deviant peers on nonviolent and violent antisocial behaviours in middle-and late-adolescence. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 9(2), 75-82.