1. Introduction

Educational theories offer various methods to promote student engagement and cognitive growth. Born in Brazil in the 20th century, the critical educator Paulo Freire introduced two radically different educational models: Banking Education and Problem-Posing Education[1]. Aligning these models through the constructivist learning theory, which posits that learning is an active process whereby learners construct meaning[2], allows for a broader understanding of their efficacy, particularly in the context of modern education. This research aims to compare the impact of Banking Education and the "Problem-Posing" education model on student engagement, proactiveness, sense of responsibility, and learning outcomes in virtual classrooms.

Paulo Freire's educational framework consists of two distinctive pedagogical paradigms: the banking model and the problem-posing model. In the banking model, knowledge is vested in the all-knowing instructor, who serves as the depositor. Students, in this context, are cast as passive "containers" awaiting the infusion of knowledge from the educator[3]. Conversely, the problem-posing model represents an active learning approach, where teachers or students pose inquiries, and the entire class collaboratively explores solutions. This approach nurtures critical and creative thinking, contrasting with the mere transmission of knowledge. It emphasizes student participation in the knowledge creation process through dialogue, interaction, rigorous questioning of subject matter, and practical application in real-world contexts, thus enhancing learners' abilities[4]. In the problem-posing model, genuine learning arises from the collective actions, dialogues, reflections, and interventions of both educators and students within the classroom[5]. This approach also promotes classroom engagement and the exploration of fundamental concepts essential for addressing complex issues. These principles align with the constructivist perspective, which asserts that learning is an active and socioculturally situated process[2].

Through our literature review, we found that previous research has conducted comprehensive comparisons between the banking model and the problem-posing model within real classroom settings, unveiling significant distinctions between these two pedagogical approaches. Suarlin's quasi-experimental study in natural class groupings demonstrated the clear effectiveness of the problem-posing model in improving students' academic performance, compared to the conventional banking model. The banking model, with its one-way knowledge transmission, tends to neglect individual learner needs, minimizing student agency and classroom participation. In contrast, the problem-posing approach boosts student engagement, creativity, and active participation through interactive learning and critical thinking[6]. Observing the implementation of problem-posing principles within the classroom, as highlighted by Brown, the educational environment evolved into a platform where community issues and topics became the focal point of discussion and problem-solving opportunities. This transition empowered educators to delve into and challenge students' individual interests and beliefs, creating a classroom atmosphere better aligned with the preferences of adolescent learners. Consequently, students reframed their perspective of the classroom from a mere examination center to an environment of greater educational resonance[3]. In the domain of English language instruction, Nelson's application of the "problem-posing" model to young learners consistently demonstrated an inclination to accommodate each learner's distinctive realities. Characterized by a flexible and less standardized structure, this approach received a favorable reception among the student population[7].

Prior research indicates the significant advantages of the problem-posing model, including increased student engagement, enhanced creativity, and greater curriculum flexibility when compared to the conventional banking model. However, this research has mainly focused on these models in physical classrooms. Our objective is to investigate the application of these models in online education. Over the past few decades, the proliferation of computers and the internet has enabled remote learning opportunities for students across all levels of education. This has led to the emergence of K-12 online education. Despite the potential of these technologies, teachers often face challenges when incorporating them into their teaching methods[8]. Compared to traditional classrooms, virtual classrooms offer limited interaction in terms of quality and quantity due to the physical separation of teachers and students. This can result in decreased student engagement and the absence of face-to-face interactions, which may lead to missed nuances and visual cues. These disparities can affect the quality of the virtual classroom and student engagement[9]. Hence, the thrust of this participatory action research lies in a comprehensive exploration of the divergent impacts of the banking model and the problem-posing model in the context of online virtual classrooms, situated within the framework of the modern digital age.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

Our investigation employs a participatory action research approach, emphasizing the essential role of participants as integral members of the community under study. Within this framework, our goal is to examine and ultimately enhance the pedagogy and educational practices.

The research consists of three key stages:

• Stage 1 - Theoretical Analysis: This study focuses on Freire’s two educational models, namely the Banking model and the Problem-Posing model. We begin with a theoretical analysis and a discussion of these models.

• Stage 2 - Implementation: Stage 2 consists of two substages. Given our findings in Stage 1, we proceed to implement the Problem-Posing model with the study’s sample.

• Substage 1 - Trial 1: Researchers implement the Problem-Posing model and maintain field notes on students' learning outcomes.

• Substage 2 - Trial 2: Researchers reflect on the learning outcomes recorded in the field notes, summarizing findings and identifying limitations from the implementation in Substage 1. We then reapply the Problem-Posing model to the study’s participants.

• Stage 3 - Reflection & Evaluation: In this stage, we evaluate the effectiveness of the two educational models using a quantitative scale of attitude and class engagement, as rated by the researcher.

2.2. Data Collection

Data will be collected through field notes, with the researcher maintaining eight weeks of virtual field notes from September to November 2022, as face-to-face interactions were precluded by COVID-19 procedures. The observations will be guided by specific criteria, including the ability and tendency of the students to complete assignments, the apparent effort they invest in completing assignments, and their understanding of the coursework. These observations then would be framed within the operational criteria, where mandated homework and guided presentations and lectures are categorized as aspects of the banking education model while allowing students to choose their readings, subjects, and homework assignments, as well as establishing dialogues with students, fall under the domain of problem-posing education. The collected data will primarily consist of both general and focused observations made on the two students, allowing the researcher to incorporate the two education models. Reflections on these observations will be conducted to further inform the analysis.

3. Stage 1: theoretical analysis

3.1. Banking Model

Paulo Freire's concept of banking education describes a pedagogical approach in which education is simplified to a process of depositing knowledge, with teachers acting as depositors and students as recipients. In this system, teachers deliver information and make deposits, while students passively receive, memorize, and reproduce this knowledge. This characterizes the "banking" model of education, where students are limited to the role of receiving, storing, and regurgitating deposits. It is worth noting that in this system, individuals themselves are archived, rather than just knowledge[10]. Within the banking education system, the teacher-student relationship is static, with teachers assumed to be the sole bearers of knowledge. Teachers are often perceived as all-knowing, while students are regarded as having minimal knowledge. Teachers deposit knowledge into students' minds without encouraging them to question or think critically. In this framework, teachers are the thinkers, students are not; teachers select content, and students conform to it. Teachers hold authority, while students submit to it[4]. In the banking model of education, students do not actively participate in the co-creation of knowledge alongside teachers and their peers.

This method of presenting decontextualized information for rote memorization not only discourages active engagement but also contradicts findings in cognitive research, suggesting its ineffectiveness[11]. Scholars like Matusov critique this approach for its one-sided delivery of knowledge to passive students, portraying the world as static and unalterable. Consequently, while the banking education system may yield higher test scores, it falls short in enabling students to genuinely comprehend and critically master the acquired knowledge[4]. As a result, banking education is generally considered an ineffective pedagogical method.

3.2. Problem Posing Model

In opposition to the banking education model, Paulo Freire proposed the "problem-posing" educational approach[5]. Fundamentally, problem-posing learning is a model that requires students to generate questions and learn problem-solving by actively engaging in questioning. Embracing the problem-posing model instills in students the habit of inquiry and hones their ability to pose questions. This approach diversifies the sources of information for students, extending beyond teachers and fostering greater student engagement and active involvement in scientific analysis. The act of posing questions challenges students' thinking and enriches their knowledge base[6].

According to this model, teachers and learners collaboratively discuss and analyze their experiences, feelings, and perceptions of the world. The problem-posing model suggests that the roles of learners and teachers are fluid, allowing students to transition from passive audiences to essential co-investigators in dialogues with their teachers[10]. Regarding the teacher's role, Freire asserts that while teachers maintain authority, they should avoid becoming authoritarian. Their interventions are aimed at helping learners reflect on various aspects of their cultural, social, and gender constructs, thus promoting critical thinking among students[5]. In Freire's own words, "Teachers are no longer merely the ones who teach but those who are being taught in dialogue with students, who, in turn, while being taught, also teach"[11]. The implementation of the problem-posing teaching method not only elevates the rigor of the classroom but also empowers learners to shift from rote memorization to critical thinking and creativity. Simultaneously, the teacher's role evolves from being the controller of information to a facilitator[3].

3.3. Unpacking Pedagogical Strategies of Banking Model and Problem-Posing Model

In order to assess the performance of the banking model and the problem-posing model in virtual classrooms, it's essential to understand how these approaches are implemented. Firstly, the banking education model represents a traditional teaching method that often relies on predetermined, curriculum-centered course materials, syllabi, or manuals without considering the perspectives or prior knowledge of learners[5]. Learning within this model primarily involves activities such as reading, observing, listening, and imitation, resulting in superficial changes in behavior or appearance[6].

Secondly, let's delve into the fundamental applications of the problem-posing model. Freire's generative themes approach promotes student-centered learning, emphasizing that teachers don't merely accept students' knowledge, emotions, and understanding without questioning. Teachers actively facilitate the learning process, and both students and teachers play pivotal roles in this approach, fostering an environment of mutual trust and forming non-hierarchical learning circles[4]. Dialogues are foundational in problem-posing classrooms, serving as a bridge between educators and learners[1].

3.3.1. Building a Trusting Atmosphere

Freire advocates that humility and respect create an atmosphere characterized by trust. In many cases, learning occurs when there's mutual respect and understanding between teachers and learners. Teachers challenge and guide learners' emotions and knowledge, allowing for meaningful learning to take place[5].

3.3.2. Non-Hierarchical Learning Circles

Learning circles, which operate in a non-hierarchical fashion, provide a platform for participants to discuss generative themes relevant to their lives. Creating a democratic space where every voice is given equal importance is crucial. This often requires proactive efforts as it doesn't typically develop organically. It might involve challenging existing power dynamics related to culture, gender, and social hierarchies. Within learning circles, progress is made collectively, not limited to isolated "star students"[6].

3.3.3. Fostering Dialogue

Dialogue is the catalyst for the transformation of existing ideas and the generation of new knowledge. To achieve this, it's imperative to establish a "dialogic" relationship between teachers and students. Human development occurs not in silence but through language, action, and reflection. Dialogue thus stands as a cornerstone of the learning process. Facilitating dialogue between two engaged parties promotes mutual goodwill, signifying a courageous act, not a display of weakness[5]. Furthermore, it's crucial for questions to be raised by either teachers or students to provide a context that resonates with the students, enabling them to relate the learning content to their personal experiences. When tasks are genuinely relevant to students' lives, they transcend mere grading instruments[11]. Teachers should create pertinent contexts, present questions or challenges, and collaborate with students to scrutinize and resolve these issues. This approach encourages students to challenge their existing thought structures and accumulate new knowledge[6].

4. Stage 2: implementation

4.1. Substage 1

In the participatory action research aimed at contrasting Freire's Banking and Problem-Posing education models, observations from Substage 1 revealed significant insights. Notably, within Field Note 1, a transition to a new reading platform demonstrated adaptability among students, indicating a departure from the passive absorption advocated by the Banking model towards the more interactive Problem-Posing approach. Moreover, students choosing longer and more complex passages, coupled with instances of peer learning, highlighted a shift from mere receivers of knowledge to active participants in their learning journey. However, Field Note 2 exposed limitations in applying the Problem-Posing model, especially when technology failed to act as a facilitator. When students turned off their cameras, it posed a challenge in maintaining the dialogical method central to Problem-Posing. Furthermore, a basic understanding of fractions with denominators was noted, but students struggled with denominators, revealing gaps in conceptual understanding that the Problem-Posing model aims to fill through dialogue and reflection. Continuing with Field Note 3, the persistent struggle with common denominators accentuated the need for revisiting foundational concepts within the Problem-Posing framework, which was not adequately addressed in the Banking model. The presence of technology, while initially thought to be beneficial, did not necessarily equate to higher engagement or understanding, marking a critical reflection point for integrating digital tools in Problem-Posing education. Lastly, Field Note 4 emphasized that students’ reluctance to engage with longer reading passages and the technical difficulties experienced shed light on intrinsic motivation issues and the importance of a responsive educational setting, which are crucial elements in Freire's dialogical model.

These observations call for strategic improvements in substage 2. Addressing technical difficulties by implementing backup plans and ensuring a range of engagement strategies will be crucial. Conceptual understanding must be deepened through varied teaching methods, such as visual aids and interactive activities that encourage a hands-on approach. Balancing peer dynamics and ensuring all students are active contributors will foster a more inclusive learning environment. Lastly, aligning closely with the principles of Problem-Posing education, by creating dialogues that promote critical thinking and student-generated problems, will be vital in overcoming the limitations observed in Substage 1.

4.2. Substage 2

In the exploration of Freire’s pedagogical models within the virtual fieldwork setting, Field Note 5 from Substage 2 provides direct evidence contrasting the Banking and Problem-Posing education models in a practical context. During a reading comprehension session with Student A and Student B, a pivot in the students' enthusiasm was observed upon shifting from a mathematical focus to a reading comprehension activity. The initially planned 45-minute session was condensed to 30 minutes at the students' request due to their eagerness to participate in Halloween festivities. Despite this reduction in time, the students committed to focusing intently and working diligently, exemplifying the central tenet of the Problem-Posing model that values active engagement and critical thinking over passive reception of information. Notably, the students' improvement in reading comprehension and their critical thinking during the activity were marked. Student A's willingness to work through unfamiliar words with the aid of Student B and myself, and notably, Student B's proactive approach to seeking help with an unfamiliar word, illustrates a significant engagement with the learning material. This dynamic where students support one another and actively engage with the content exemplifies the collaborative and dialogic approach emphasized by Freire's Problem-Posing education. The observations noted in Field Note 6 continue this theme, where the flexibility offered to the students, allowing them to finish the session early in exchange for focused work, appeared to result in increased productivity. This instance not only reflects the adaptability necessary in educational settings but also underscores the importance of motivational factors in student engagement, an aspect sometimes overlooked in the more rigid Banking model. In the mathematics-focused Field Note 7, a collaborative 2-on-2 tutoring session was organized to provide additional support to Student A in mathematics, as suggested by the school supervisor. The involvement of multiple tutors, as well as the supervisor's direct engagement in monitoring the session, provided a structured yet interactive environment conducive to the Problem-Posing model. The students' engagement was high, and the competitive yet collaborative dynamic between Student A and Student B, especially in the instances where they competed to answer first or helped each other, reflects an active and problem-oriented learning approach.

The reflection on these field notes suggests that a condensed yet intensive and engaging learning session can be more effective than a longer, less focused one. The Problem-Posing model's focus on critical thinking and collaboration was evident in the students' active participation and willingness to engage with complex texts and mathematical problems. Conversely, these observations also point to limitations inherent in the Banking model, where a more rigid approach may not account for individual student needs or foster the same level of critical engagement.

These field notes provide valuable insights into the practical application of Freire’s educational models, with evidence supporting the effectiveness of a Problem-Posing approach in engaging students actively and collaboratively in their learning process.

5. Stage 3: reflection and evaluation

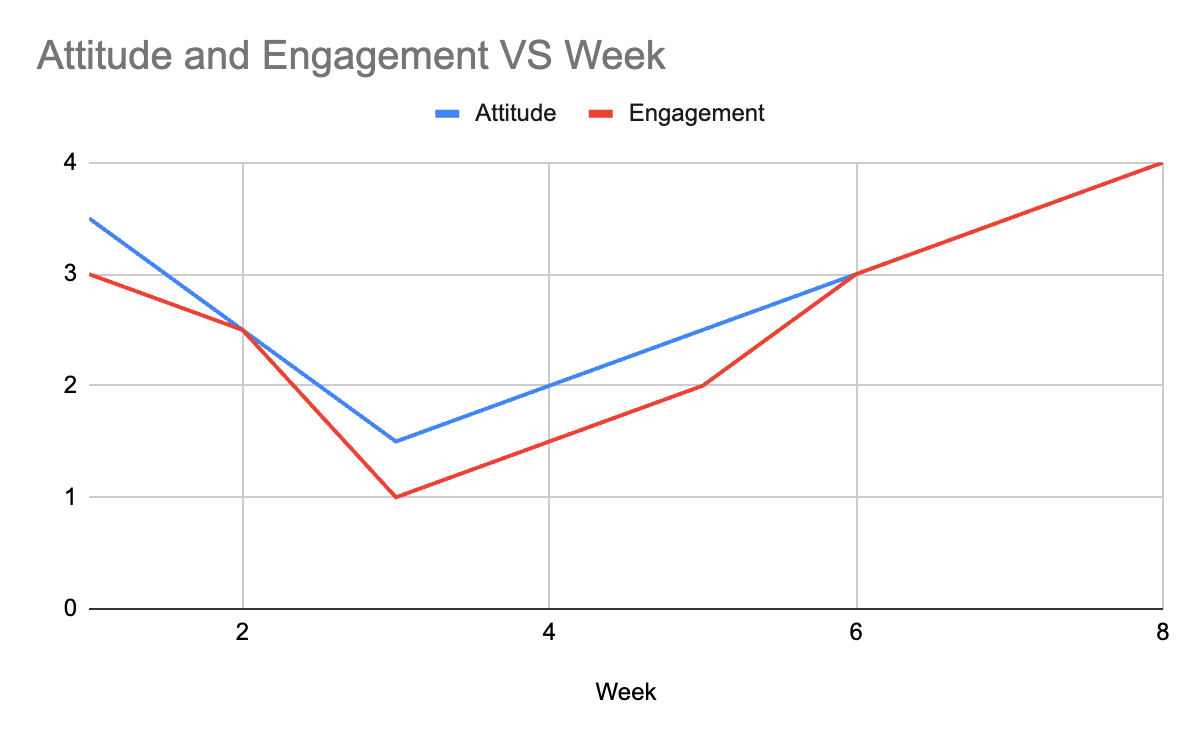

In the third stage of this action study, we assess the effectiveness of the two models by employing a quantitative scale to measure attitudes and class engagement. These assessments are conducted by the researcher. Following each section of the study, the researcher evaluates students’ average learning outcomes across two distinct categories: learning attitude and class engagement, using a rating scale ranging from 0 to 4. It is important to mention that no grades or test performances were collected during this evaluation, owing to privacy and ethical considerations. It is noteworthy that the coding of these two variables was performed by a single researcher, ensuring the data’s reliability.

Figure 1 illustrates the results of the utility of the two teaching models throughout class time over the eight-week period. The rating scale used for this assessment ranges from 1 to 4, with 1 representing the lowest score and 4 indicating the highest. The average scores for attitude and engagement during weeks 7 and 8 stood out as the highest throughout the eight-week duration.

Figure 1: Students’ Attitude & Engagement VS. Week

A detailed examination of the field notes indicates that the problem-posing method significantly influenced these scores. Both Field Notes 7 and 8 highlight instructors employing an interactive teaching approach, encouraging students to actively analyze and resolve ratio problems, aligning with the principles of the problem-posing method.

In week 2, students demonstrated moderate attitudes and class engagement, as depicted in Figure 1. According to Field Note 2, both banking and problem-posing teaching methods were introduced; however, it was the problem-posing method that fostered active problem-solving and critical thinking. Conversely, week 3 recorded the lowest average score. One plausible explanation could be the limited interaction among students, the instructor, and peer-to-peer interactions. Field Note 3 emphasizes the absence of the problem-posing educational method during this week.

Upon reflection on our study, it becomes evident that students’ attitude and class engagement demonstrate a positive correlation with the implementation of the problem-posing model, underscoring its efficacy in comparison to banking education. This finding provides evidence supporting the beneficial impact of problem-posing models in learning situations. It suggests the need for further exploration and implementation of these models in similar educational settings, emphasizing the potential for future research to delve deeper into their effectiveness.

6. Discussion

6.1. Implications

Our research is rooted in the theoretical framework established by Paulo Freire’s two educational models. In the context of online education and constructivism, our study illuminates the discernible positive effects on various aspects of the educational experience—student engagement, initiative, responsibility, and learning outcomes. Central to our findings is the observation that an emphasis on dialogue and collaboration in this educational paradigm cultivates a more profound and enduring connection between students and the subject matter, thereby encouraging the development of lifelong learning habits and critical thinking skills. Moreover, this pedagogical approach positions students as active and engaged participants in their own educational journey, a critical imperative in the face of our rapidly evolving and information-abundant world.

In a larger context, problem-posing pedagogy can be considered as an application of constructivist learning theory. Constructivism asserts that learners actively construct knowledge individually and socially[2]. This theory emphasizes that learning is an active process, involving interaction between learners and the world. Language plays a crucial role in learning and influences the process. Learning is inherently social, involving interactions with teachers, peers, family, and acquaintances. Recognizing the social aspect of learning is essential for successful education. In contrast to traditional approaches that isolate learners, problem-posing education acknowledges the social nature of learning and integrates dialogue, interaction, and collaborative knowledge application into the learning process[2].

6.2. Limitations

The limitations of this study warrant careful consideration. Notably, the utilization of a small and highly specific sample, comprising just two students from St. Anthony’s School, raises valid concerns about the study’s external validity and representative nature of the sample. Although this limited sample size facilitates thorough documentation and close observation of the selected participants, it presents challenges when attempting to extrapolate the findings to a broader educational context. The distinctive characteristics of the two students may not be representative of the wide spectrum of experiences and responses encountered in larger, more diverse populations. As such, this study can be regarded as a case study rather than full blown experiment. And in order to establish a causal relationship between the effectiveness of the pedagogies of interest here, we suggest conducting an experimental study with a larger sample size.

Additionally, the choice of a convenient sampling method has the potential to introduce bias in participant selection, stemming from factors like availability or willingness to participate. This bias could skew the study's outcomes and restrict their broader applicability. The generalizability of the findings to other educational settings or student populations is thus compromised. Furthermore, the reliance on virtual data collection, necessitated by Covid-19 restrictions, may limit the depth of interactions and observations, which is particularly concerning as it may hinder the capture of the full spectrum of nuances in student behavior and responses.

7. Conclusion

Using a participatory action study, our study’s result suggests that the problem-posing educational methods, in the realm of virtual education, produced discernible, real-time improvements in student engagement and performance, as marked in Stage 3. Students exhibited greater willingness to complete their assigned tasks, were more attentive in class, demonstrated increased problem-solving autonomy, and engaged more actively with both their peers and the teacher. In the problem-posing model, education transforms into a collective, collaborative, and societal endeavor characterized by cognitive dialogues among participants[5]. This is consistent with the constructivist view, which emphasizes that learners construct knowledge and meaning individually and in a social context during the learning process[2]. Thus, we view problem-posing as a practical application of constructivist principles in teaching. In stark contrast, the banking educational methods yielded a less positive response from students, who tended to be reticent and withdrawn, exhibited a visible lack of interest in the content, and displayed hesitancy in completing their assignments. The finding of this study aligns with what Freire contends, the oral curriculum, reading requirements, 'knowledge' assessment methods, the distance between the teacher and the learner, and promotion criteria in the banking model are all employed to eliminate critical thinking, embracing instead an immediate and utilitarian approach[3].

The study’s limitations, particularly the small sample size and potential bias, should serve as a foundation for future research, prompting researchers to address and expand upon these constraints. Subsequent studies may consider enlarging the sample size to enhance generalizability and mitigate potential biases. Moreover, they could explore alternative data collection methods, potentially integrating both virtual and in-person approaches when feasible, to enrich the depth of observations. These refinements will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of pedagogical practices and their applicability in broader educational contexts.

Acknowledgement

Zhiwo Xu, Yingshan He, and Chun Wang contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

References

[1]. Freire, P., Ramos, M. B., Macedo, D. P., Shor, I., & Freire, P. (2020). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Bloomsbury Academic.

[2]. Hein, G. E. (1991). Constructivist learning theory. https://www.exploratorium.edu/education/ifi/constructivist-learning

[3]. Brown, P. M., (2013). An Examination of Freire's Notion of Problem-Posing Pedagogy. https://esploro.libs.uga.edu/esploro/outputs/doctoral/An-examination-of-Freires-notion-of-problem-posing-pedagogy-the-experiences-of-three-middle-school-teachers-implementing-theory-into-practice/9949332805302959

[4]. Akinsanya, P.O., Ojotule, A.P. (2022). Freire’s Critical Pedagogy and Professional Teachings in the Twenty-First Century. Unizik Journal of Educational Research and Policy Studies VOL.14 (3): 145-160

[5]. Rugut, E. J., & Osman, A. A. (2013). Reflection on Paulo Freire and Classroom Relevance. American International Journal of Social Science, Vol. 2 No. 2, 23–28.

[6]. Suarlin, S., Negi, S., Ali, M. I., Bhat, B. A., & Elpisah, E. (2021). The impact of implication problem posing learning model on students in high schools. International Journal of Environment, Engineering and Education, 3(2): 69–74.

[7]. Nelson, N., & Chen, J. (2022). Freire’s problem-posing model: Critical pedagogy and Young Learners. ELT Journal, 77(2): 132–144.

[8]. Thampi, M. (1973). The Educational Thought of Paulo Freire [Review of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, by P. Freire]. Social Scientist, 2(1): 91–95.

[9]. Oliveira Dias, Dr. M., Albergarias Lopes, Dr. R., & Teles, A. C. (2020). Will virtual replace classroom teaching? lessons from virtual classes via zoom in the times of covid-19. Journal of Advances in Education and Philosophy, 04(05): 208–213.

[10]. Luo, T., Murray, A., (2018) Connected Education:Teachers’ Attitudes towards Student Learning in a 1:1 Technology Middle School Environment. Journal of Online Learning Research, 4(1):87-116.

[11]. Karan, E., & Brown, L. (2022). Enhancing students’ problem-solving skills through Project-Based Learning. Journal of Problem Based Learning in Higher Education.

Cite this article

Xu,Z.;He,Y.;Wang,C. (2024). A Comparative Analysis of Banking and Problem-Posing Models in Online Platform—An Action Research. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,61,40-52.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Freire, P., Ramos, M. B., Macedo, D. P., Shor, I., & Freire, P. (2020). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Bloomsbury Academic.

[2]. Hein, G. E. (1991). Constructivist learning theory. https://www.exploratorium.edu/education/ifi/constructivist-learning

[3]. Brown, P. M., (2013). An Examination of Freire's Notion of Problem-Posing Pedagogy. https://esploro.libs.uga.edu/esploro/outputs/doctoral/An-examination-of-Freires-notion-of-problem-posing-pedagogy-the-experiences-of-three-middle-school-teachers-implementing-theory-into-practice/9949332805302959

[4]. Akinsanya, P.O., Ojotule, A.P. (2022). Freire’s Critical Pedagogy and Professional Teachings in the Twenty-First Century. Unizik Journal of Educational Research and Policy Studies VOL.14 (3): 145-160

[5]. Rugut, E. J., & Osman, A. A. (2013). Reflection on Paulo Freire and Classroom Relevance. American International Journal of Social Science, Vol. 2 No. 2, 23–28.

[6]. Suarlin, S., Negi, S., Ali, M. I., Bhat, B. A., & Elpisah, E. (2021). The impact of implication problem posing learning model on students in high schools. International Journal of Environment, Engineering and Education, 3(2): 69–74.

[7]. Nelson, N., & Chen, J. (2022). Freire’s problem-posing model: Critical pedagogy and Young Learners. ELT Journal, 77(2): 132–144.

[8]. Thampi, M. (1973). The Educational Thought of Paulo Freire [Review of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, by P. Freire]. Social Scientist, 2(1): 91–95.

[9]. Oliveira Dias, Dr. M., Albergarias Lopes, Dr. R., & Teles, A. C. (2020). Will virtual replace classroom teaching? lessons from virtual classes via zoom in the times of covid-19. Journal of Advances in Education and Philosophy, 04(05): 208–213.

[10]. Luo, T., Murray, A., (2018) Connected Education:Teachers’ Attitudes towards Student Learning in a 1:1 Technology Middle School Environment. Journal of Online Learning Research, 4(1):87-116.

[11]. Karan, E., & Brown, L. (2022). Enhancing students’ problem-solving skills through Project-Based Learning. Journal of Problem Based Learning in Higher Education.