1. Introduction

In the era of ubiquitous internet access and the proliferation of social media platforms, the showcasing of individual affluence, commonly termed as "wealth flaunting", has emerged as a notable sociological phenomenon. Such displays, highlighting materialistic wealth, opulent lifestyles, and social standing, have invariably captured widespread public scrutiny and discourse. Notably, among the youth demographic — a cohort at a pivotal juncture of self-identity formation and psychological maturation — these digital portrayals might exert significant ramifications on their self-perception and mental well-being. How these individuals construe their relationship with others and appraise their intrinsic worth and societal position can be fundamentally intertwined with their enduring psychological health and subjective well-being.

Drawing from the paradigm of Social Comparison Theory, which postulates the inherent human proclivity to assess oneself via others, individuals are predisposed to engage in social comparisons to delineate their standing and competence across varied dimensions. Such comparative evaluations might be upward, juxtaposing oneself against those perceived as superior, or downward, against those perceived as inferior.

Integrating the premises of Social Comparison Theory, the primary objective of this research endeavor is to elucidate whether exposure to digital wealth flaunting precipitates heightened sentiments of inferiority or neuroticism among the youth. By delving into this inquiry, it is anticipated that a more nuanced understanding of the psychological implications of online affluence displays on youth can be garnered, offering theoretical foundations for pertinent educational and psychological interventions.

1.1. Internet Exposure (Conspicuous online contents)

The rise of social media has brought about a new mode of social interaction, with conspicuous consumption content becoming increasingly popular on these platforms. According to research by Lee Kar Wai and Syuhaliy Osman, conspicuous consumption is on the rise in both developing and developed countries [1]. This type of consumption behavior not only reflects an individual's level of wealth but has also become a way for young people to gauge their own and others'social status. While these displays of wealth and luxury lifestyles on social media are often enviable, they can also have a distorting effect on young people's self-identity.

Emerging adulthood is a critical period for the formation of personal identity and self-esteem. Research by Kolanska-Stronka and Gorbaniuk indicates that emerging adults, more than other age groups, pay close attention to their peers and seek social recognition through the acquisition of expensive goods and services [2]. This demonstrates a prevalent social perception among young people that places importance on self-esteem, with a tendency to shape their self-esteem through the approval of others. Brands have become a tool for emerging adults to express their identity, helping them to establish their self-concept within social groups [2]. Thus, conspicuous consumption content on social media is not just a display of material wealth but also a means for emerging adults to form self-identity and boost self-esteem. However, in an environment where online flaunting of wealth is common, the boundary recognition between normative expectations and goals begins to blur for the youth, potentially distorting their perceptions of self-worth and success.

During the period of self-identity formation in emerging adults, they are easily influenced by the display of digital wealth, which can have adverse effects on their self-perception. Lehdonvirta's research shows that people are increasingly inclined to publicly display their material possessions and lifestyle online, further intensifying the trend of conspicuous consumption [1]. These behaviors receive widespread dissemination and recognition on social media, providing a new symbol of social identity. However, young people, as the main users of social media, are particularly sensitive to such displays. According to Wai and Osman, "Self-esteem can influence people's behaviors and encourage the appearance of certain behaviors"[1]. Due to the ubiquity and convenience of the internet, youth can easily display luxury goods on social media to enhance their self-esteem, which is positively reinforced by their vanity. In other words, during this critical period of self-identity formation, young people are susceptible to the influence of these digital displays of wealth, which may lead them to have unrealistic expectations of success and adversely affect their self-esteem and behavior. Additionally, the roots of conspicuous consumption trace back to Veblen's "Theory of the Leisure Class" proposed in 1899, which incorporated social status into traditional economic theory [1]. In the context of social media, conspicuous consumption becomes a means of exhibiting personal social status. Individuals may use luxury consumption to enhance their image on social media and potentially boost their self-esteem [3]. In this digital age, the behavior of conspicuous consumption has become more convenient and widespread, allowing people to easily showcase their wealth and lifestyle to a global audience. According to Wai and Osman, luxury goods not only express personal identity and social status but also enhance self-esteem [1].

On social media platforms, users post images and videos related to a luxurious lifestyle, such as designer clothes, luxury cars, and travel destinations, to build and maintain their social image. The core of this consumption pattern is to elevate one's status by purchasing and displaying goods associated with high social standing. This consumption is non-productive; its main purpose is to showcase one's level of wealth and to differentiate oneself from others. With unique social media interactions like likes, comments, and shares, the displays of conspicuous consumption are amplified, thereby influencing people's perceptions of personal value and success. At the same time, the role of conspicuous consumption in boosting self-esteem is very complex. On one hand, it might make an individual feel more confident, as the positive feedback on social media can be interpreted as a signal of public recognition of the poster's wealth and status. On the other hand, this reliance on external validation for self-esteem can be fragile because it is based on others' feedback on material luxury rather than recognition of intrinsic personal value. While conspicuous consumption can temporarily enhance an individual's sense of social status and self-esteem, this form of identity construction based on youth can be harmful. As Wai and Osman stated, "When a person is experiencing a low level of self-esteem, they tend to engage in activities that can help them raise their self-esteem,"[3]. It exacerbates materialism, potentially leading to dissatisfaction and unease at both individual and societal levels. It reveals that youths, through comparison with others and judging their own self-esteem levels, may change their view of money when they perceive their self-esteem to below, possibly leading them to mimic the extravagant spending behaviors of other online wealth flaunters or even engage in false displays of affluence.

1.2. Emerging adults and social media

The distinct life-course phase of emerging adults from traditional transition occurs during the late teenage years and continues into the twenties situated between teenagers and adulthood. They are a symbol of a human developmental and forming period known as psychological moratorium, which is a critical time to explore worldviews and personal values to influence their transitions into adulthood. During this period, emerging adults embark on the journey of learning to live independently, communicate with others, and excel in academic performance. It is through discovering their life's purpose and meaning that they strive to experience and explore the world. They assess their progress based on the decisions they make regarding their desired living standards. For the majority of emerging adults, their decision-making process is influenced by various factors, including the guidance and support of family members or other caring adults, mentors, social networks, and other support systems [4].

These individuals and networks play a crucial role in shaping their choices and providing them with the necessary guidance and resources to navigate through this transitional phase of life [5]. In the early 21 century, the internet environment plays a crucial role in influencing their development [6]. Emerging adults are using internet more frequently than people in other age groups. One survey conducted by Statistics and Informatics in 2012, demonstrated that the young population aged 19 to 24 years has the highest rate of Internet use, accounting for 67.2% among different population groups [6]. Arnett, et al. announced that emerging adults are living in the digital realm [7]. Indeed, emerging adults often express themselves and engage with others through various social media platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, MySpace, Twitter, and Second Life. These platforms provide them with opportunities to connect, share their experiences, and seek information on a wide range of topics, including health [8].

During their formative years, individuals are exposed to diverse perspectives, cultures, and ideas through online interactions platform, which can influence their beliefs, values, and overall worldview. Social media platforms and online advertisements often showcase idealized and glamorous lifestyles, including luxury possessions, exotic vacations, and extravagant experiences. When young people constantly see these images, it can create a sense of aspiration and desire to attain similar levels of wealth and material possessions [9]. According to Viner, increased usage of social media in online platforms were associated with negative levels of emotion. Zegarra and Cuba showed that there is a relationship between self-esteem and degree of internet use in emerging adults. Bijstra et al. note that low self-esteem is critical in leading to frequent use of internet [10].

Kim et. al. [11] pointed out that the new generation of young people is easily misled by the prevailing consumerism and superficial prosperity in society. They blindly worship fashion and exhibit new consumption phenomena, such as excessive consumption, luxury consumption, and indulgent consumption. The purpose of consumption has shifted from meeting basic needs to conveying certain personal messages to society and the audience. The study also found that young American women are particularly inclined to invest in luxurious purchases to display costly-signalling consumptive status. According to Giovannini et al. [12], the display of conspicuous consumption is also evident among college students, who pursue designer brands and fashion. Some do it to showcase their unique taste, while others flaunt their wealth, insisting on buying only expensive, branded, and trendy items. They use consumer symbols to boast about their identity, status, and economic power, aiming to evoke envy, respect, and jealousy from others, and to gain admiration and satisfy their own vanity and sense of honour.

1.3. Social comparison and self-esteem

The social comparison theory suggests that individuals evaluate themselves by comparing their own attributes, abilities, and achievements with those of other people [13]. According to Festinger, self-evaluations are easily influenced by the choice of comparison targets. This is known as downward social comparison when people tend to compare themselves to those who perform slightly worse in a certain aspect. When people compare themselves to those who perform worse, they feel more valuable and the self-esteem increases. However, people compare themselves to those who are more capable or popular, known as upward social comparison. The result of such comparisons is usually a blow to the self-esteem [14].

The impact of social comparison on individual well-being is crucial for comprehending human behavior within any social context [15]. During emerging adulthood, individuals undergo a process of value formation, influenced by their experiences and interactions with the world around them. This period is characterized by self-discovery, questioning of traditional norms, and the development of personal beliefs. The educational and social environments provide opportunities for emerging adults to explore different perspectives, challenge existing beliefs, and shape their own values. However, the influence of media, including social media, can also impact their value formation process [16]. The rise of social media platforms has revolutionized the way emerging adults interact and perceive themselves and others. Online platforms often showcase curated versions of individuals' lives, emphasizing material possessions, luxurious lifestyles, and achievements [17]. Most people cannot easily ignore the statistical results reported by the media or societal role models. When ones are forced to compare themselves to these external standards, their self-evaluation decreases, and their self-esteem diminishes. The culture of flaunting wealth and success can trigger social comparison among emerging adults, leading to feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt. The constant exposure to others' seemingly perfect lives can create unrealistic expectations and contribute to a sense of inferiority. The perception of yourself becomes more negative when you see your friends showing off on social media. From another contrary view, whenever upward social comparison occurs, some feel a strong desire to do something to narrow the gap between themselves and the comparison target, in order to restore their self-esteem to its previous level.

Additionally, the prevalence of online platforms and the culture of flaunting success can lead to social comparison and fluctuations in self-esteem among emerging adults. It is crucial to promote a supportive environment that encourages individuality, self-acceptance, and critical thinking to help emerging adults navigate these challenges and develop a strong sense of self [16].

1.4. Literature review

Shaw et al. conducted a study to test the hypothesis that Internet usage can have a beneficial effect on users, which found that internet use significantly increased self-esteem [18]. Mehdizadeh study investigate the most widespread social platform, a new method of self-presentation by collecting personality self-reports from 100 users [19], where most individuals of global internet users participate in sharing information, tastes, feelings, and experiences according to García-Domingo et. al. [20]. Cha et. al. present evidence that on social networking platforms, social comparison activities are developing into three different patterns, like lateral comparison, downward comparison, and upward comparison [21]. What’s more, social media users tend to engage in upward social comparisons with individuals who excel in various aspects, rather than seeking happiness from those who are less fortunate in life [22].

Conversely, in a world profoundly impacted by the ubiquity of social media, it is imperative to scrutinize the impact of exposure to social media-based social comparison on user`s negative emotions on social media platforms. In the study conducted by Anixiadis et al. in 2019, researchers observed that when thin-idealized images of users' bodies were posted on social media platforms, there were noticeable effects on individuals' state mood and body dissatisfaction. As a result of upward body comparison thoughts and a desire to the body depicted, individuals may experience negative mood changes [23]. Rüther et al. examined the effects of positivity-biased images of female social media influencers on the state self-esteem of female participants. The results of regression analyses revealed that when exposed to these images, participants engaged in upward social comparisons, which subsequently predicted lower levels of state self-esteem [24].

Increasing of social media usage is closely linked to an individual's mental well-being, especially increasing negative mood. Boers et. al. uses an annual study to test significant relationships between screen time, self-esteem, and social media throughout 4 years. The results indicate that more screen time is linked to upward social comparison, and the interaction between between-person and within-person associations regarding social media and self-esteem supports the concept of reinforcing spirals [25]. Yang et. al. provides the underlying mechanisms for the relationship between social media use and social anxiety through the questionnaire with 470 undergraduates as participants. The results showed that social media use intensity has positive relation with social anxiety. In Study 1, social media use leads to upward social comparison, which in turn contributes to social anxiety, and Social media use leads to upward social comparison, which affects self-esteem, ultimately contributing to social anxiety. In Study 2, a total of 180 participants were divided into two groups: the experimental group and the control group. The experimental group was exposed to content commonly accessed by undergraduates on social media, while the control group was exposed to landscape documentaries. The researchers measured the participants' levels of upward social comparison, self-esteem, and social anxiety. The results indicated that participants in the experimental group reported higher levels of social anxiety compared to those in the control group. This finding demonstrates a causal relationship between social media exposure and social anxiety [26].

In conclusion, these studies offer valuable insights into how emerging adults manage their self-esteem in relation to social media usage and online portrayals of wealth. However, their primary focus lies in examining the impact of self-perception and mental well-being on the use of social media platforms. That is that individuals with higher or lower self-esteem tend to exhibit a stronger association between social media usage and upward social comparison.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were randomly selected from the public, and 95.2% of them are college students. 447 participants completed the survey. This research provided three age ranges, namely less than 18 years old, 18-26 years old, and older than 26 years old. Since this study is conducted on emerging adults, the research chose to use the 314 participants (118 male, 196 female) aged 18-26 years.

2.2. Measures

The Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale is a widely used instrument for evaluating individual self-esteem. It is an 8-items scale that measures both positive and negative feelings about oneself. All items are answered using a 5-point Likert scale format ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. For the four positive questions, give “Strongly Disagree” 1 point, “Disagree” 2 points, “Neither agree or disagree” 3 points, “Agree” 4 points, and “Strongly Agree” 5 points. For the four negative questions, the scores were reversed. Sum all scores up for 8 items. Higher score means higher self-esteem. The research also measured the mean and standard deviation for the self-esteem score.

The frequency of flaunting wealth content is measured by a multiple-choice question with four options, which are almost not, rarely, sometimes, and often. These four options match the scale from 1 to 4 (almost not is 1, often is 4) for future analyze.

Basic information such as age, gender and job are also measured in the questionnaire.

2.3. Procedure

Participants were assured of complete confidentiality at the outset of this questionnaire and no personal information would be recorded or disclosed. The study was presented as an online questionnaire via WeChat. First, participants provided sociodemographic data and basic questions about the frequency of network use and social comparison. Next, they completed the measures of Rosenberg self-esteem scale.

2.4. Analyses

The research used Pearson Correlation to analyze two variables, the frequency of viewing content showing off wealth on internet and the self-esteem score.

\( r=\frac{\sum ({x_{i}}-\bar{x})({y_{i}}-\bar{y})}{\sqrt[]{{\sum ({x_{i}}-\bar{x})^{2}}\sum {({y_{i}}-\bar{y})^{2}}}} \) (1)

3. Results

3.1. Correlation

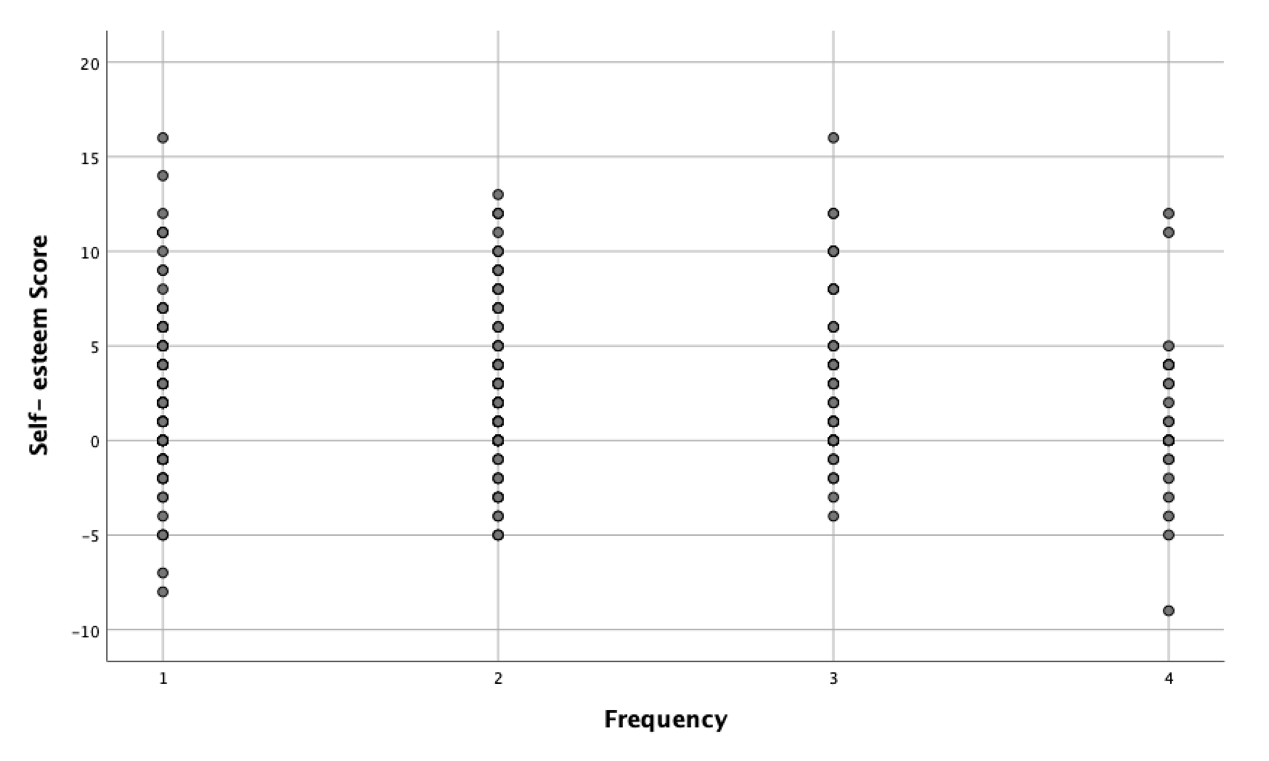

The research investigated the correlation between frequency of viewing content showing off wealth on internet and the self-esteem score and found a weak negative linear relationship exists between the two variables (r = -.03). The value of -0.03 is very close to 0, which suggests that there is almost no linear correlation between the two variables. In practical terms, changes in one variable do not reliably predict changes in the other.

Figure 1: Interaction between Frequency of wealthy content viewed and self-esteem score.

Table 1: Pearson Correlation between Frequency of wealthy content viewed and self-esteem score.

Correlations | |||

Self-esteem Score | Frequency | ||

Self-esteem Score | Pearson Correlation | 1 | -.030 |

Sig.(2-tailed) | .596 | ||

N | 314 | 314 | |

Frequency | Pearson Correlation | -.030 | 1 |

Sig.(2-tailed) | .596 | ||

N | 314 | 314 | |

3.2. Mean and Standard Deviation

The research analyze the mean and standard deviation for the self-esteem score and got a mean of 2.37 and a standard deviation of 4.102. The standard deviation of 4.102 is relatively high compared to the mean of 2.37, suggesting that there is considerable spread or variability around the average self-esteem score 2.37 which is not significantly high or low.

4. Discussion

The study tried to find a connection between how young adults come across displays of wealth on the internet and their self-esteem. Surprisingly contrary to what was expected based on Social Comparison Theory there was a weak correlation (r = -0.03) found between the frequency of encountering flaunted wealth online and self-esteem. This result shows that the impact of flaunting wealth content is not as straightforward as previously believed on young individuals' self-esteem.

There might be complex reasons since the research received this slightly negative correlation. For instance, it is possible that some other factors affect the correlation, such as an individuals’ resilience or their ability to critically assess online content. These factors might cause further thinking for emerging adults against the effects of comparing themselves to others who display wealth on the internet. Furthermore, the weak correlation may reflect how younger generations interpret the displays of wealth on social media. This generation might be skeptical regarding the authenticity of the online wealth content. Also, when evaluating themselves, they may prioritize different aspects such as skills and personal achievements rather than material possessions.

People might question the previous idea of how wealth content impacts self-esteem since the study got this result. Moreover, the result shows that the research may need to do further studies on the impact of social media. If the connection is not as strong as previously believed, people might need to consider focusing on something else, such as emphasize the development of critical-thinking skills in individuals, especially in emerging adults.

It would be beneficial to explore factors that could influence the connection between flaunting social media wealth and self-esteem. This could involve research tracking changes over time or qualitative studies providing deeper insights, into individual experiences. Through investigations, the research may uncover how young adults handle and respond to online displays of wealth as well as how these behaviors affect their self-esteem. While this study indicates that there may be an influence of showcasing wealth online on the self-esteem of young adults it opens avenues for further exploration of the complex factors at play. Moreover, it urges us to reconsider interventions that aim to support the healthy development of self-perception among young people in the digital age. Of solely focusing on shielding young adults from the impact of social media emphasizing the cultivation of media literacy skills and nurturing a strong sense of self identity could prove more advantageous. By embracing these approaches young individuals can adeptly navigate the challenges presented by media and maintain a positive self-image in a society where the boundaries, between reality and online presence are increasingly blurred.

5. Limitation and Future Directions

This paper has numerous limits, providing opportunities for further investigations. First, the generalizability of the survey's results is limited by the sample. The research focuses on Chinese emerging adults between the ages of 18-26. This limitation on population and age might lead to bias in the findings. Self-esteem can fluctuate across the lifespan and ethnic groups [27], so results of Chinese emerging adults might not apply to older or younger individuals with cultural differences. Aligning with the difference in social media platforms, the result might not apply to people living in Western countries, which would harm the generalizability of the study. So, future researchers should research other countries and generations to examine the generalizability of the result.

Second, using a survey to assess the participants' self-esteem can introduce response bias. Participants may exaggerate or hide their true self-esteem due to various factors. For example, people with low self-esteem may report a higher score, or people with high self-esteem may report a lower value to present themselves in a generally favorable range. Furthermore, different people may have different portrayals and perceptions of self-esteem. A person with individual variations in their concept of self-esteem may not provide data that aligns with the research's intended measurement. These subjectivities can affect the validity of findings. Future researchers can include a more diverse measure of self-esteem and compare the results to reduce the impact of response bias.

Third, the third variable problem could confound the results because the research focuses solely on the correlation between social media usage frequency and self-esteem. For instance, personality traits like neuroticism and openness can influence social media users' responses to internet content. People with the same frequency of exposure but different personalities could result in different levels of self-esteem. Failing to control for these variables might lead to erroneous conclusions about the impact of social media. Due to these factors, the result may need to include essential factors that could alter the result. Future researchers can control confounders like personality traits and genders to provide a more accurate depiction.

Finally, the study only captures data at a single point due to the time limitation. So, it only provides a snapshot of the relationship between social media usage and self-esteem. However, people's perception of upward social comparison and self-esteem is flexible. So, people's recent experience would change both measures and affect the results. For instance, if a person has just browsed content related to showing off wealth, he may give a higher rating in the survey about the frequency and lower self-esteem. As a result, it would report a false correlation between self-esteem and upward social comparison, which would further affect the results of the study. To eliminate such factors, future researchers could adopt a longitudinal design that tracks the same individuals over time. This approach can explore the changes in social media usage and the fluctuation of self-esteem within individuals and provide a more solid result.

6. Conclusion

The research explored the relationship between exposure to wealth-flaunting content on social media and self-esteem among Chinese youth aged 18-26. The findings suggest a weak negative correlation between the frequency of viewing wealth-displaying content on social media and the level of self-esteem among Chinese youth. This challenges the traditional view under Social Comparison Theory that increased exposure to such content significantly impacts self-esteem negatively. While the results indicate that the impact of online wealth flaunting on self-esteem is not as pronounced as previously thought, it does not negate the potential psychological implications. Factors such as individual resilience, critical media literacy, and prioritizing personal achievements over material wealth may mediate this relationship. It is important to acknowledge that this generation might view and interpret social media content differently, potentially being more skeptical of the authenticity of online wealth displays. The limitations of the research, including its reliance on a specific demographic group and self-reported measures, highlight the necessity for further research. Future studies should aim to expand the demographic scope, incorporate longitudinal designs, and control for additional variables such as personality traits and stimuli, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of these dynamics. In conclusion, the study contributes to the ongoing discourse on the impact of social media on emerging adults’ psychology. It underscores the necessity for educational interventions focusing on the development of values and perspectives on money among emerging adults, with an emphasis on developing critical thinking and media literacy skills. These skills are crucial in helping emerging adults navigate the complex social media environment, discern misinformation, and maintain a healthy self-perception in an increasingly digital world.

Authors’ Contributions

DZ, YQ, YW and KL: conceptualization, visualization and project administration. DZ: investigation, writing-original draft preparation, review, editing and supervision. YQ: writing-introduction, Internet Exposure (Conspicuous online contents) and conclusion. YW: methodology and writing-discussion. KL: writing-limitation and further directions. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

Dingding Zhou, Yuelin Qiu, and Yahe Wu contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

References

[1]. Wai, L. K., & Osman, S. The Influence of Self-esteem in the Relationship of Social Media Usage and Conspicuous Consumption. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Socal Sciences, 2019, 9(2), pp.335–352.

[2]. Kolańska-Stronka M., & Gorbaniuk, O.Materialism, conspicuous consumption, and brand engagement in self-concept: a study of teenagers. current issues in personality psychology, 2022, 10(1), pp.39-48.

[3]. Widjajanta B., et Al. The impact of social media usage and self-esteem on conspicuous consumption: instagram user of hijabers community Bandung member. Inernational Journal of E-Business and E-Government Studies Vol 10, 2018, (2), pp. 1-13.

[4]. Wood D, Crapnell T, Lau L, Bennett A, Lotstein D, Ferris M, Kuo A, Emerging Adulthood as a Critical Stage in the Life Course, 2017 Nov 21, In: Halfon N, Forrest CB, Lerner RM, Faustman EM, editors, Handbook of Life Course Health Development [Internet], Cham (CH): Springer, 2018, PMID: 31314293.

[5]. Woolsey, Lindsey; Katz-Leavy, Judith (2008), Transitioning Youth with Mental Health Needs to Meaningful Employment and Independent Living, The Journal for Vocational Special Needs Education, volume 31, pp9-18.

[6]. Government of Peru, National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (Peru), Peru National Household Survey on Living Conditions and Poverty 2015, Lima, Peru: National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (Peru).

[7]. Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen, Digital Natives: Emerging Adults’ Many Media Uses, Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties, Oxford University Press, 23 Oct. 2014, pp.194-210

[8]. Thomas, P.N. (2014), Development Communication and Social Change in Historical Context, In The Handbook of Development Communication and Social Change (eds K.G. Wilkins, T. Tufte and R. Obregon), pp. 5-19 https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118505328.ch1

[9]. Brown, V. (2023), Navigating identity formation via clothing during emerging adulthood, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, Vol.ahead-of-print, No. ahead-of-print, https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-01-2023-0019

[10]. Viner RM, Gireesh A, Stiglic N, Hudson LD, Goddings AL, Ward JL, Nicholls DE. Roles of cyberbullying, sleep, and physical activity in mediating the effects of social media use on mental health and wellbeing among young people in England: a secondary analysis of longitudinal data, Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 2019 Oct;3(10):685-696. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30186-5, Epub 2019 Aug 13. Erratum in: Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020 Jan;4(1): e4. PMID: 31420213.

[11]. DongHee Kim, SooCheong (Shawn) Jang, Motivational drivers for status consumption: A study of Generation Y consumers, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Volume 38, 2014, pp 39-47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.12.003.

[12]. Giovannini, S., Xu, Y. and Thomas, J. (2015), Luxury fashion consumption and Generation Y consumers: Self, brand consciousness, and consumption motivations, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 22-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-08-2013-0096

[13]. Wood, J. V. (1989), Theory and research concerning social comparisons of personal attributes, Psychological Bulletin, 106(2), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.231

[14]. Buunk BP, Collins RL, Taylor SE, VanYperen NW, Dakof GA., The affective consequences of social comparison: either direction has its ups and downs, J Pers Soc Psychol, 1990 Dec, 59(6):1238-49, doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.6.1238. PMID: 2283590.

[15]. Suls, J. (2000), Opinion Comparison, In: Suls, J., Wheeler, L. (eds) Handbook of Social Comparison, pp 105–122, The Springer Series in Social Clinical Psychology, Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4237-7_6

[16]. Hu, Y.-T., Liu, Q.-Q., & Ma, Z.-F., Does upward social comparison on SNS inspire emerging adults materialism? focusing on the role of self-esteem and mindfulness, The Journal of Psychology, 2022, 157(1), pp.32–47, https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2022.2134277

[17]. Burnasheva, R., & Suh, Y. G., The influence of social media usage, self-image congruity and self-esteem on conspicuous online consumption among millennials, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 2020, 33(5), pp.1255–1269, https://doi.org/10.1108/apjml-03-2020-0180

[18]. Shaw LH, Gant LM., In defense of the internet: the relationship between Internet communication and depression, loneliness, self-esteem, and perceived social support, Cyberpsychol Behav, 2002 Apr;5(2):157-71, doi: 10.1089/109493102753770552.

[19]. Mehdizadeh, S. (2010), Self-presentation 2.0: Narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook, Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(4), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0257

[20]. Marta García-Domingo, María Aranda, Virginia María Fuentes, Facebook Use in University Students: Exposure and Reinforcement Search, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, Volume 237, 2017, pp. 249-254, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2017.02.071.

[21]. Cha, Kyung & Lee, Eun. (2015), An Empirical Study of Discontinuous Use Intention on SNS: From a Perspective of Society Comparison Theory, The Journal of Society for e-Business Studies, 20, pp.59-77, 10.7838/jsebs.2015.20.3.059.

[22]. Yitshak Alfasi, The grass is always greener on my Friends' profiles: The effect of Facebook social comparison on state self-esteem and depression, Personality and Individual Differences, Volume 147, 2019, pp. 111-117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.032.

[23]. Anixiadis, F., Wertheim, E. H., Rodgers, R., & Caruana, B. (2019), Effects of thin-ideal Instagram images: The roles of appearance comparisons, internalization of the thin ideal and critical media processing, Body Image, 31, pp.181–190, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.10.005

[24]. Rüther L, Jahn J, Marksteiner T, #influenced! The impact of social media influencing on self-esteem and the role of social comparison and resilience, Front Psychol, 2023, Oct 4, 14:1216195. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1216195.

[25]. Boers E, Afzali MH, Newton N, Conrod P., Association of Screen Time and Depression in Adolescence, JAMA Pediatr, 2019 Sep 1, 173(9):853-859, doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1759.

[26]. Feng Yang, Minyan Li, Yang Han, Whether and How Will Using Social Media Induce Social Anxiety? The Correlational and Causal Evidence from Chinese Society, Frontiers in Psychology, 2023, Sep29, vol14, 1217415, 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1217415.

[27]. Ninot, G., Fortes, M., & DeligniÈres, D. (2005), The dynamics of self-esteem in adults over a 6-month period: An exploratory study, The Journal of Psychology, 139(4), 315–330, https://doi.org/10.3200/jrlp.139.4.315-330.

Cite this article

Zhou,D.;Qiu,Y.;Wu,Y.;Li,K. (2024). The Influence of Digital Affluence Display on Emerging Adults Self-Esteem. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,60,55-65.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Wai, L. K., & Osman, S. The Influence of Self-esteem in the Relationship of Social Media Usage and Conspicuous Consumption. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Socal Sciences, 2019, 9(2), pp.335–352.

[2]. Kolańska-Stronka M., & Gorbaniuk, O.Materialism, conspicuous consumption, and brand engagement in self-concept: a study of teenagers. current issues in personality psychology, 2022, 10(1), pp.39-48.

[3]. Widjajanta B., et Al. The impact of social media usage and self-esteem on conspicuous consumption: instagram user of hijabers community Bandung member. Inernational Journal of E-Business and E-Government Studies Vol 10, 2018, (2), pp. 1-13.

[4]. Wood D, Crapnell T, Lau L, Bennett A, Lotstein D, Ferris M, Kuo A, Emerging Adulthood as a Critical Stage in the Life Course, 2017 Nov 21, In: Halfon N, Forrest CB, Lerner RM, Faustman EM, editors, Handbook of Life Course Health Development [Internet], Cham (CH): Springer, 2018, PMID: 31314293.

[5]. Woolsey, Lindsey; Katz-Leavy, Judith (2008), Transitioning Youth with Mental Health Needs to Meaningful Employment and Independent Living, The Journal for Vocational Special Needs Education, volume 31, pp9-18.

[6]. Government of Peru, National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (Peru), Peru National Household Survey on Living Conditions and Poverty 2015, Lima, Peru: National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (Peru).

[7]. Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen, Digital Natives: Emerging Adults’ Many Media Uses, Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties, Oxford University Press, 23 Oct. 2014, pp.194-210

[8]. Thomas, P.N. (2014), Development Communication and Social Change in Historical Context, In The Handbook of Development Communication and Social Change (eds K.G. Wilkins, T. Tufte and R. Obregon), pp. 5-19 https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118505328.ch1

[9]. Brown, V. (2023), Navigating identity formation via clothing during emerging adulthood, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, Vol.ahead-of-print, No. ahead-of-print, https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-01-2023-0019

[10]. Viner RM, Gireesh A, Stiglic N, Hudson LD, Goddings AL, Ward JL, Nicholls DE. Roles of cyberbullying, sleep, and physical activity in mediating the effects of social media use on mental health and wellbeing among young people in England: a secondary analysis of longitudinal data, Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 2019 Oct;3(10):685-696. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30186-5, Epub 2019 Aug 13. Erratum in: Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020 Jan;4(1): e4. PMID: 31420213.

[11]. DongHee Kim, SooCheong (Shawn) Jang, Motivational drivers for status consumption: A study of Generation Y consumers, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Volume 38, 2014, pp 39-47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.12.003.

[12]. Giovannini, S., Xu, Y. and Thomas, J. (2015), Luxury fashion consumption and Generation Y consumers: Self, brand consciousness, and consumption motivations, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 22-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-08-2013-0096

[13]. Wood, J. V. (1989), Theory and research concerning social comparisons of personal attributes, Psychological Bulletin, 106(2), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.231

[14]. Buunk BP, Collins RL, Taylor SE, VanYperen NW, Dakof GA., The affective consequences of social comparison: either direction has its ups and downs, J Pers Soc Psychol, 1990 Dec, 59(6):1238-49, doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.6.1238. PMID: 2283590.

[15]. Suls, J. (2000), Opinion Comparison, In: Suls, J., Wheeler, L. (eds) Handbook of Social Comparison, pp 105–122, The Springer Series in Social Clinical Psychology, Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4237-7_6

[16]. Hu, Y.-T., Liu, Q.-Q., & Ma, Z.-F., Does upward social comparison on SNS inspire emerging adults materialism? focusing on the role of self-esteem and mindfulness, The Journal of Psychology, 2022, 157(1), pp.32–47, https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2022.2134277

[17]. Burnasheva, R., & Suh, Y. G., The influence of social media usage, self-image congruity and self-esteem on conspicuous online consumption among millennials, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 2020, 33(5), pp.1255–1269, https://doi.org/10.1108/apjml-03-2020-0180

[18]. Shaw LH, Gant LM., In defense of the internet: the relationship between Internet communication and depression, loneliness, self-esteem, and perceived social support, Cyberpsychol Behav, 2002 Apr;5(2):157-71, doi: 10.1089/109493102753770552.

[19]. Mehdizadeh, S. (2010), Self-presentation 2.0: Narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook, Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(4), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0257

[20]. Marta García-Domingo, María Aranda, Virginia María Fuentes, Facebook Use in University Students: Exposure and Reinforcement Search, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, Volume 237, 2017, pp. 249-254, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2017.02.071.

[21]. Cha, Kyung & Lee, Eun. (2015), An Empirical Study of Discontinuous Use Intention on SNS: From a Perspective of Society Comparison Theory, The Journal of Society for e-Business Studies, 20, pp.59-77, 10.7838/jsebs.2015.20.3.059.

[22]. Yitshak Alfasi, The grass is always greener on my Friends' profiles: The effect of Facebook social comparison on state self-esteem and depression, Personality and Individual Differences, Volume 147, 2019, pp. 111-117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.032.

[23]. Anixiadis, F., Wertheim, E. H., Rodgers, R., & Caruana, B. (2019), Effects of thin-ideal Instagram images: The roles of appearance comparisons, internalization of the thin ideal and critical media processing, Body Image, 31, pp.181–190, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.10.005

[24]. Rüther L, Jahn J, Marksteiner T, #influenced! The impact of social media influencing on self-esteem and the role of social comparison and resilience, Front Psychol, 2023, Oct 4, 14:1216195. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1216195.

[25]. Boers E, Afzali MH, Newton N, Conrod P., Association of Screen Time and Depression in Adolescence, JAMA Pediatr, 2019 Sep 1, 173(9):853-859, doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1759.

[26]. Feng Yang, Minyan Li, Yang Han, Whether and How Will Using Social Media Induce Social Anxiety? The Correlational and Causal Evidence from Chinese Society, Frontiers in Psychology, 2023, Sep29, vol14, 1217415, 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1217415.

[27]. Ninot, G., Fortes, M., & DeligniÈres, D. (2005), The dynamics of self-esteem in adults over a 6-month period: An exploratory study, The Journal of Psychology, 139(4), 315–330, https://doi.org/10.3200/jrlp.139.4.315-330.