1. Introduction

1.1. Emphasizing Individual Language Experience of Students

The formation of students’ individual language experience is always in dynamic language practice, and how students’ language learning occurs is a significant focus. The 2022 curriculum standards frequently mention, across various content sections, that learning happens in real and meaningful contexts and challenging tasks. All learning activities are based on students’ autonomy, voluntariness, self-awareness, and self-consciousness. How do students engage in language learning? The curriculum standards clearly describe the actual learning situations in the Chinese language curriculum. The core literacy cultivated by the compulsory education curriculum standards is accumulated and constructed in active language practice activities and demonstrated in real language use situations. This means that the more complex the language context students enter, the richer the language practice activities they experience, and the more targeted and operational their individual language experience becomes.

1.2. Requirements of the Curriculum Standards

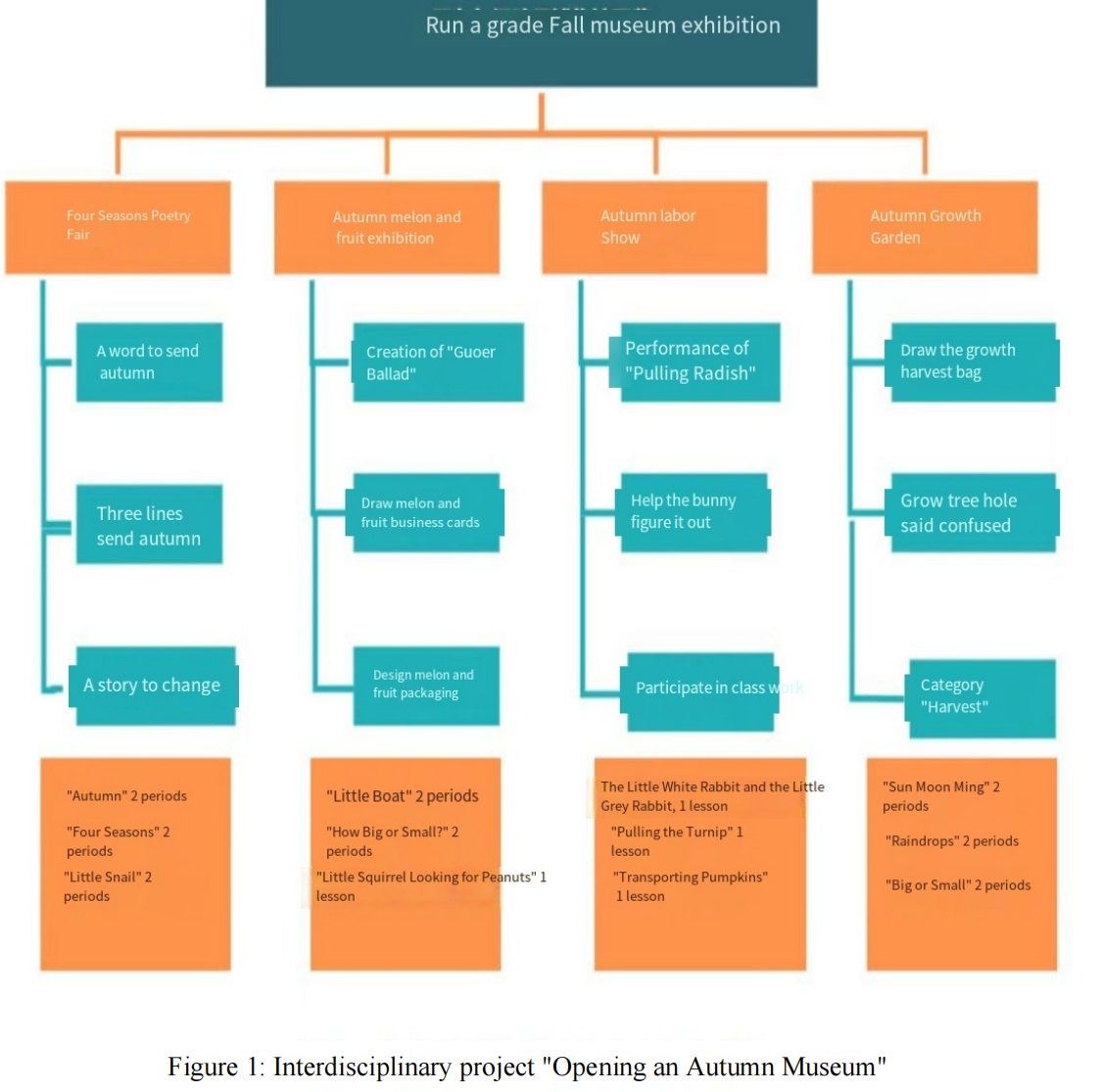

Interdisciplinary learning is prominently reflected in this excerpt from the new compulsory education curriculum standards: “Guide students in Chinese language practice activities to connect in-class and out-of-class, school and community, broaden the fields of Chinese language learning and use; around meaningful topics in academic learning and social life, engage in reading, sorting, inquiry, and communication activities, and in the process of comprehensively applying multidisciplinary knowledge to discover, analyze, and solve problems, improve language and text application skills.” [1] Teachers should utilize the ubiquitous Chinese learning resources and practice opportunities, guiding students to pay attention to experiences related to family life, campus life, and social life, enhancing their awareness of learning and using Chinese in various contexts. They should guide students to learn language and text application skills in diverse everyday life scenarios and social practice activities, fully exploring the application of Chinese literacy in interdisciplinary learning. The interdisciplinary project “Autumn Museum” fully integrates Chinese, mathematics, science, labor, and art subjects.

The Chinese curriculum should guide students in real language use situations, accumulating language experience through autonomous language practice activities. Students’ language learning should originate from the real need for language use in life and serve to solve real-life problems. This approach stimulates students’ interest and enthusiasm in exploring and solving problems. Based on real needs and problems, focusing on problem exploration and resolution, this fully embodies the practical essence of the Chinese curriculum. It also reflects the language practice learning atmosphere and environment created by a practical language classroom. Such situational designs are generally based on textbook content and contextual features. [2]

1.3. Authentic Learning Tasks

Learning tasks arise in specific contexts and aim to achieve particular goals by comprehensively applying the relevant knowledge and skills acquired to solve real problems. The task activities mentioned in the 2022 curriculum standards indicate that teachers no longer focus on instruction and mechanical practice but start with teaching content. This approach is based on authentic language use contexts, integrating listening, reading, and writing activities, and setting challenging learning tasks. Students are given clear task objectives and engage in activities such as sorting, inquiry, and collaboration to solve real problems, thereby cultivating their language use abilities. [3]

In this process, tasks are set in specific contexts, the goals aim to solve real problems, and activities are the means to complete the tasks. In this design, the activity goals of the Autumn Museum are broken down into individual learning tasks, allowing students to develop their Chinese literacy progressively through these tasks.

Figure 1: Interdisciplinary project “Opening an Autumn Museum”

2. The Value and Practical Path of Creating Learning Situations

2.1. Three Elements of Learning Situations

To explore how to create real and meaningful Chinese learning situations, it is first necessary to clarify the core elements of a learning situation. Drawing on relevant research findings and practical experiences from both domestic and international sources, I believe that teaching objectives are the soul of a learning situation. A Chinese learning situation should consist of three core elements: the background that serves the objective, the problem corresponding to the objective, and the task to achieve the objective.

2.1.1. Background Serving the Objective

The background serving the objective refers to the themes, characters, things, events, and their relationships that are selected, edited, and assembled based on the current learning objective. This background can be a real social event, a piece of text, or an image. The background is the material for constructing the learning situation, but it is not equivalent to the learning situation itself.

2.1.2. Problem Corresponding to the Objective

The problem corresponding to the objective refers to the problems or conflicts set in the constructed specific scenario based on the current learning objective. These problems and conflicts determine whether the learning situation can trigger the students’ cognitive process and are the core of constructing the compelling structure of the learning situation. True learning occurs when students mobilize all their experiences, prior knowledge, and strategies to overcome one or a series of obstacles.

2.1.3. Task to Achieve the Objective

The task to achieve the objective refers to the concretization and gradation of the solution methods for the problems and conflicts set based on the current learning objective. This means the specific things that students are clearly required to do within a specified time and according to certain requirements in the learning situation. In task design, it is sometimes necessary to provide students with certain learning scaffolds to facilitate their gradual completion of tasks from shallow to deep.

2.2. The Path and Practice of Creating Learning Situations

First, the textbook resources, such as the texts “Autumn,” “The Four Seasons,” and “The Little Snail,” are used to create contextual roles, allowing children to better immerse themselves in the content. The situation is the context involved in classroom teaching content. In specific first-grade Chinese language teaching, based on the psychological cognitive characteristics of first-grade students, a step-by-step teaching strategy of “concrete perception—emotional experience—thought expression” is clarified using the textbook. Through the learning theme and practical activities of the Autumn Poetry and Prose Exhibition, interdisciplinary learning situations, literary experience and cultural participation situations, and daily life situations are created to stimulate students’ enthusiasm for literary reading and creative expression.

Overall, the situational settings of the three texts under the autumn theme are combined with the seasonal theme of autumn in the curriculum, relying on the typical scenes of children’s existing life experiences and campus life, and providing detailed interpretations of the language characteristics and textual features of “Autumn,” “The Four Seasons,” and “The Little Snail.”

2.2.1. Setting Situations Based on Students’ Cognitive Characteristics

The situational setting for “Autumn” is “The Magician of Autumn.” At the beginning, the teacher creates a situational task for the students, asking them to collect and illuminate nine magic gems given by the Magician of Autumn and embark on a journey to find the magic of autumn with the magician. Using language, students experience an immersive situational experience, discovering the hidden magic in autumn. Through individual reading, group reading, and comparative reading, students gradually and independently feel the magical changes brought by autumn. Continuing to use the situation to guide students’ learning, they further discover other magical changes of autumn. At this time, students transform into leading geese, thoughtful geese engaging in immersive role-based reading, and experience emotional reading by assuming roles. Finally, students discover many more hidden magical changes in autumn, realizing that the magic of autumn changes everything in nature. The magician reappears, inviting the students, accompanied by music, to present autumn poetry to autumn. In this fairytale-like scene, students’ interest is greatly stimulated.

2.2.2. Setting Situations Based on Chinese Language Elements

The situational setting for the text “The Four Seasons” is “The Magician of the Four Seasons.” At the beginning of the class, the role of “The Magician of the Four Seasons” is created. She is a magical magician who waves her wand and conjures up many little elves such as grass buds, lotus leaves, grain spikes, and snowmen. Then, the children, wearing headpieces of the little season elves, perform a role-play reading of the elves of the four seasons, experiencing an immersive role-playing activity. Finally, “The Magician of the Four Seasons” reappears and issues a challenge task: to present a poem for each season. The children transform into little elves of the various seasons and create seasonal nursery rhymes. In short, through various situations, the children engage in repeated role experiences, personal participation, and situational performances. This immersive learning experience within the situations stimulates their enthusiasm for literary reading and creative expression.

2.2.3. Setting Situations by Connecting to Life

“The Little Snail” is a story about the changes of the four seasons, where the tool used is the creation of a story using three magical elements discovered and proposed by the children based on their learning of the story. First, “turning fragments into a whole,” where students realize that the story unfolds in the order of the seasons through a picture, also gaining an understanding of the cyclical pattern of the seasons. Second, “comparative observation,” where students grasp that each season has its representative scenery with distinct characteristics. Third, recognizing that the story unfolds with the repeated phrase “crawling, crawling” of the little snail, highlighting the recurrence of key phrases in the language of the picture book. In this process, the value of the situation is fully explored, and students step by step engage in learning within the situation, enhancing their expressive literacy.

3. Building and Practicing Tools Based on Chinese Literacy

3.1. Visualization Tools for Thinking

In the sub-task “Four Seasons Poetry Meeting,” situational creation is carried out to inspire children’s desire to express. How can we ensure that every child has something to say and can articulate complete and even aesthetically pleasing sentences? This requires the teacher to set up specific and appropriate tools.

3.1.1. Tool One: Pictures

“Autumn” serves as the introductory lesson, where the first magical tool is a large number of vivid and intuitive pictures. These pictures, sourced from life and the campus, help students observe and discover the changes brought by autumn, providing them with content to talk about. The second magical tool is constructing sentence patterns for students to follow. The core of the “Autumn” text is the word “change,” and the most basic sentence pattern in the text serves as the minimum goal for students’ expressive output, guiding them to focus on the changes of autumn while encouraging and respecting their diverse and free-form verbal expressions. “The Four Seasons” is a playful nursery rhyme with a strong rhythmic sense, and performing recitations is a form of creative expression. Suitable rubrics guide children to add expressions and actions to interpret the little poem. This helps students accumulate classic language patterns and develop a good sense of language. The second magical tool for “The Four Seasons” is also sentence construction, but it progresses from the single autumn sentence. First, children discover similarities and try using reduplication to say a sentence, then notice differences and practice by imitation. Using two different sentence patterns, they create three-line oral poems; an optional format is provided where children choose representative items of the seasons and make name cards for them, encouraging them to engage in written creation through drawing and writing.

3.1.2. Tool Two: Senses

In life, beauty is not lacking; what is lacking is the eyes to discover beauty. Perceiving beauty actually requires us to engage all our senses. Utilizing the five senses can help students broaden their thinking, experience deeply, and inspire diverse cognition. In this process, their language expression will also evolve from being monotonous to becoming enriched.

Additionally, teachers guide students to create “Four Seasons Magic Name Cards,” encouraging children to share their completed cards with friends, thereby expanding their cognition and language skills. Such writing and drawing activities allow children to connect life with literature, expressing their emotional experiences through artistic and literary forms. The mastery of beautiful language requires accumulation, replication, and reinforcement, which engraving these forms onto paper will deepen children’s impressions and continuously immerse them in literary environments indoors.

3.1.3. Tool Three: Sequence and Repetition

“The Little Snail” is a story about the changing seasons. The tools constructed by the teacher are the three magic techniques for creating stories, which were proposed by children based on their exploration of the story. First is synthesis from the parts, using a picture to help students understand that the story unfolds in the sequence of the four seasons, while also fostering a regular recognition of the seasonal changes, which cycle endlessly. Second is comparative observation, understanding that each season has its representative scenery with distinctive features. By this point, our children have already grasped the basic concept that “the succession of the seasons creates the diverse beauty of nature.” Third is discovering that the story unfolds as the little snail “crawling, crawling,” which replicates key sentence patterns in picture book language. Using these three magic techniques, telling the story of the school’s four seasons to the little snail is the core task of this lesson.

The specific operational process involves the teacher dividing the students into groups of four, distributing pictures of the school’s four seasons. Group members need to observe and arrange the sequence of seasonal changes. They should then carefully observe the pictures they receive to discover the characteristics of the scenes depicted. Finally, using sensory tools, they transform these observations into key sentence patterns and connect them. They then share their work on stage, presenting the four seasons composite images through posters, and creating stories about the school’s four seasons.

3.2. Design and Application of Evaluation Tools

In a “language practice-oriented classroom,” it is essential to establish an integrated classroom operation mechanism of “teaching - learning - assessment” based on pragmatic teaching objectives. This ensures that the individual language experiences of students, centered on pragmatic competence, are genuinely enhanced. Pragmatic assessment is not only an important component of students’ language practice activities but also provides precise feedback on students’ pragmatic current status and fosters precise reflection on their language practices.[4] In a “language practice-oriented classroom,” precise feedback and reflection require designing evaluation scales from two perspectives: first, the linguistic expression level, which assesses whether the application of pragmatic knowledge enhances students’ current language proficiency, coherence, specificity, and clarity; second, the language communication level, which evaluates whether oral and written language align with role identities, whether the tone and wording match task contexts, and whether the content persuades and captivates the audience. Pragmatic assessment is divided into two levels: self-assessment by students, reflecting on and evaluating themselves against the evaluation scales, and peer assessment, where students engage in interactive discussions within small groups, and more importantly, across the entire class, introducing task scenarios, assuming role identities, and providing real-time evaluations of pragmatic communication effectiveness.

Learning a language and applying it involves a gradual process. Initially, individuals may have limited language knowledge and poor pragmatic skills. However, as they grow older, their language knowledge expands continuously, their pragmatic practices accumulate, and their pragmatic skills gradually improve and strengthen. [5]

4. Conclusion

In interdisciplinary tasks at the elementary school level, the design of core tasks, the development of specific sub-tasks, and their implementation all require frontline teachers to fully grasp students’ cognitive characteristics. They should view student development from various dimensions of life, create appropriate and realistic contexts, and under the impetus of tasks, develop tools that facilitate student learning. This aims to enhance student competence and establish a practice-oriented classroom, ultimately helping students improve their problem-solving abilities.

References

[1]. Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2022). Curriculum standards for compulsory education in Chinese language (2022 edition). Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press.

[2]. Guo, H. (2023). New highlights in curriculum revision: Interdisciplinary thematic learning. Primary Education Research, (01).

[3]. Li, Y. H. (2023). Insights of Chinese language core literacy on constructing teaching content. Chinese Language Teaching in Secondary Schools, (9), 4-12.

[4]. Wang, W., & He, Q. Q. (2022). Experimental research on designing learning activities and classroom evaluation to cultivate students’ problem-solving abilities. Journal of Education Studies, (10), 45-55.

[5]. Zhu, Y. S., & Jin, X. (2015). Grounding language use in constructing professional literacy of Chinese language teachers. Language Construction, (7), 14-17.

Cite this article

Zhou,J. (2024). Creating Real Situations, Developing Thinking Tools — Design and Implementation of the Interdisciplinary Project “Autumn Museum” for Lower Grades of Primary School. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,62,91-97.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Education Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2022). Curriculum standards for compulsory education in Chinese language (2022 edition). Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press.

[2]. Guo, H. (2023). New highlights in curriculum revision: Interdisciplinary thematic learning. Primary Education Research, (01).

[3]. Li, Y. H. (2023). Insights of Chinese language core literacy on constructing teaching content. Chinese Language Teaching in Secondary Schools, (9), 4-12.

[4]. Wang, W., & He, Q. Q. (2022). Experimental research on designing learning activities and classroom evaluation to cultivate students’ problem-solving abilities. Journal of Education Studies, (10), 45-55.

[5]. Zhu, Y. S., & Jin, X. (2015). Grounding language use in constructing professional literacy of Chinese language teachers. Language Construction, (7), 14-17.