1. Introduction

Deepfakes are hyper-realistic videos that are created through the use of deep learning. deepfakes rely on neural networks that analyze large amounts of data samples to learn to mimic a person's facial expressions, mannerisms, voice, and tone of voice. Through deepfakes technology, facial mapping technology and artificial intelligence are used to replace the face of one person in a video with the face of another person. Because deepfakes use real footage and real audio, they are difficult for viewers to detect. As a result, many viewers believe that the videos they are watching are real [1].

However, while this technology brings innovation, it has also become a new tool for digital crime, especially the increasing gendered digital violence against women. The most significant harm of deepfake videos lies in their realism and difficulty in distinguishing authenticity, which makes them often used to produce non-consensual pornographic videos and pictures, causing severe reputational and psychological damage to women. Women face unique challenges in the digital space, the most prominent of which is the gendered application of deepfake technology. In other words, the primary victims of deepfake technology are women, primarily through the falsification of their images or videos to spread false pornographic content. This not only contributes to the prevalence of gender-based violence on the Internet but also deepens the commodification of women's bodies. With the spread and use of these technologies on the Internet, women's privacy and social status are facing unprecedented threats. This paper will analyze the gendered application of deepfake technology through a current situation study, and further illustrate the digital crime in the context of deepfake technology. In addition, this study will also explore the social status of women under the prevalence of deepfake technology through relevant cases in South Korea, and finally this paper will put forward some relevant suggestions.

2. Gender abuse and impact of Deepfake technology

2.1. Analysis of Why Deepfake Technology Disproportionately Targets Female Victims

Deepfake technology is often used on female victims, which reflects a profound social and cultural problem. Females are often viewed as sexualized objects in cyberspace, and the application of Deepfake technology has exacerbated this phenomenon. Fake videos and photos of female images often have strong sexual connotations or pornographic nature, which is not only an insult to females but also a form of digital violence [2]. Anonymity is one of the characteristics of cyberspace, which provides a wide range of cover for perpetrators, especially in gender-based violence. The abuse of deepfake technology is usually reflected in the use of unreal female images to spread pornographic content. As mentioned above, due to the widespread use of this technology, many celebrity images have been used to make related videos. Due to the public's lack of relevant knowledge, most people find it difficult to distinguish between true and false, which promotes online gender violence. In addition, society's gender stereotypes about women have further exacerbated the harm of deepfake technology to women.

2.2. The Mechanism by which Deepfake Technology Promotes Gender-based Violence on the Internet

The anonymity and technical complexity of deepfake technology have led to cyber violence. The perpetrators can easily change their images through related software, disguise themselves as victims and spread pornographic content[2]. After being spread, such content can easily remain in cyberspace for a long time. The anonymity of netizens and the rapid spread of content make it very difficult to completely delete or prevent the spread of such false information. Even if these images and videos are fake, they can still cause irreparable damage to women's reputation and social status[3]. In addition, deepfake technology also facilitates sexual blackmail and sexual harassment on the Internet. Criminals will directly use content generated by deepfake technology to threaten women.

2.3. The Commodification of Women's Bodies and the Proliferation of Deepfake technology

The commodification of women's bodies is one of the important reasons why deepfake technology is widely used in a gendered manner. The phenomenon of women being objectified is relatively common, and women's bodies are displayed as commodities in the entertainment and fashion industries. Deepfake technology further perpetuates the objectification of women's bodies, especially when they are produced into pornographic videos without women's consent, which exacerbates the phenomenon of women being exploited[3]. This commodification has also promoted the development of deepfake technology, and pornographic platforms have made profits from it, so the exploitation of women by deepfake technology continues to exist

3. Social Norms and Women's Digital Identities

3.1. The Interaction between Gender Role Expectations and Digital Crime

The social environment has a very rigid gender positioning for women. Many people believe that women's behavior and image have fixed standards. When women's behavior does not meet social expectations, it becomes a violent act. This is also true in cyberspace. The false content generated by deepfakes takes advantage of society's commercialization and sexualization of women's bodies. In addition, gender inequality and gender discrimination issues cannot be ignored. Anonymity and deepfake features make female Internet users more vulnerable to harassment and attacks, especially some public figures and women who do not meet social stereotypes. They are often deeply affected [4]. It can be said that gender-based digital violence not only violates women's personal privacy, but also reinforces society's stereotypes about women in reality.

3.2. Social and Cultural Constraints on Women's Digital Identities and Gendered Deepfake Crimes--- A Case Study of South Korea

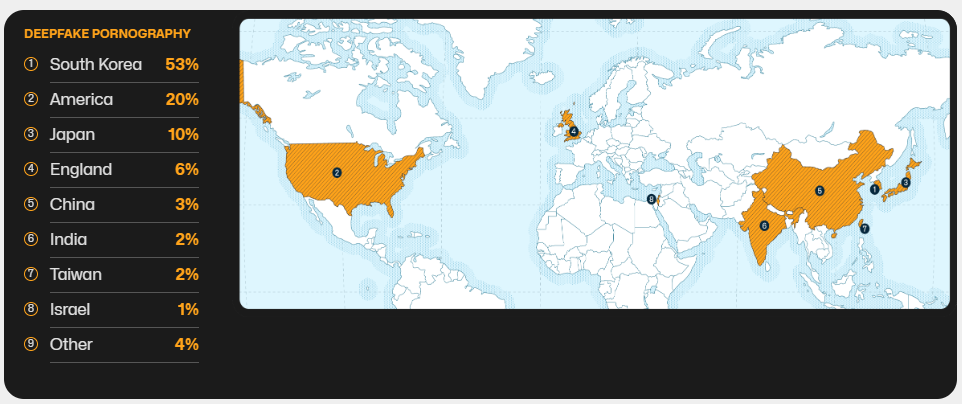

Traditional gender norms greatly affect women’s status and power. This cultural constraint is also reflected in women’s online platforms, especially in their behavior and identity construction[5]. For example, Korean society is deeply influenced by Confucian traditions. In Korean society, women are often required to accept strict moral standards and stereotyped gender roles. This also makes Korean women vulnerable to digital crime. [5]. The 2023 Deepfake Report released by a US cybersecurity company shows that nearly 100,000 pornographic videos created by AI face-changing were circulated online in 2023. Among them, 53% of the victims were from South Korea (see figure 1) [6]. Deepfake technology not only violates personal privacy, but also reflects society's commodification and control of women's images. In this cultural context, women often face tremendous social pressure and moral criticism, and it is more difficult for them to seek help when they encounter digital violence. Korean women are often defined as meek and submissive in society, so when they become victims of deep fake technology, society often tends to blame the victims and make moral judgments on them.

This phenomenon of victim blaming arises from societal expectations surrounding women's gender roles. When women step outside these prescribed roles, they often face unjust scrutiny and accusations instead of the support and protection they rightfully deserve. As a result, many victims opt to remain silent in the face of public accusations to avoid experiencing further harm.

Figure 1: Data distribution of deepfake pornography

Although the South Korean government has introduced a series of policies and laws to deal with digital gender violence in recent years in an attempt to strengthen the protection of women, the inherent concept of gender roles in society still restricts the effectiveness of these measures. To truly and effectively curb the gendered crime problems brought about by deep fake technology, South Korea needs to make profound changes at the cultural and institutional levels, reduce gendered oppression of women, and provide them with more effective support.

Women's digital identities are not only the result of personal choices, but are also deeply influenced by the social and cultural background in which they live. In many societies, women's status, rights and roles are still constrained by traditional gender norms, which restricts their self-expression in digital space. This cultural constraint is reflected in women's online behavior patterns and identity construction. Women not only face gender discrimination and inequality in real life, but are also subject to cultural and social oppression in digital space.

4. Gendered digital crime response strategies and social support

4.1. Cooperation between government and social organizations

Cooperation between the government and social organizations is crucial to dealing with the consequences of deepfakes. Legislation and law enforcement need to play their due role, and the state should also enact relevant laws to explicitly prohibit the production and dissemination of fake videos. There should also be corresponding explanations for personal online privacy laws. In the legislative process, cooperation between the government and relevant technology companies is also crucial. Through the anti-deepfake technology developed by the company, it is also possible to better discover relevant content and prevent the dissemination of related videos and pictures. In addition, social organizations also play an important role in promoting the protection and development of women. Relevant social organizations should actively carry out publicity and education activities to improve the public's knowledge reserves[7]. Social organizations can also provide some psychological and legal assistance to victims to further solve the problems caused by deepfakes.

4.2. Education and public awareness

The relevant education provided by schools to students cannot be ignored. Reform of the education system can fundamentally change the impact of gender-based violence. It is necessary to add courses on cyber violence, deep fakes and digital privacy protection to the curriculum. Students can better promote gender equality and significance through relevant courses [8]. And popular science for the public can also be promoted through some online public publicity activities. Raising public awareness can also better create an environment that supports victims. When more people understand and pay attention to the harm of deepfakes technology to women, victims will be more likely to gain social sympathy and support, reducing the social stigma of victims. In addition, public participation can also prompt governments and technology companies to take more proactive measures to deal with this emerging technological threat.

4.3. Establish a social support network

It is crucial to build a platform to help victims. Many women do not know how to protect their legal rights when faced with the infringement of deep fake technology [3]. Therefore, professional legal aid services and related legal education can help victims safeguard their own interests and combat these crimes. The social support network should include a broad community support system. By establishing victim mutual aid groups or community organizations, both online and offline, victims can have a safe space to share their experiences, offer emotional support, and provide practical advice to others facing similar challenges. These groups create a sense of solidarity, helping victims realize they are not alone in their struggles, which can significantly alleviate feelings of isolation, shame, and helplessness often associated with digital crimes like deepfakes. Through peer support, survivors can exchange coping strategies, legal resources, and guidance on how to report incidents and seek justice. In many cases, these networks become a vital platform for healing, empowering victims to regain control over their lives and rebuild their self-esteem.

5. Discussion

Deep fake technology leads to cross-border dissemination, making legal accountability and law enforcement very difficult. Victims may exist all over the world, not just in specific countries or regions. The rapidity of Internet dissemination makes these deep fake contents spread all over the world quickly, and it is difficult for victims to be held accountable. Criminals can even take advantage of legal differences and law enforcement loopholes between different countries to commit cross-border crimes. Therefore, international cooperation is essential to addressing the global challenge of gender-based digital crime. International cooperation can effectively coordinate the legal and technical resources of various countries and form a cross-border response mechanism.

Countries should pay attention to the problems caused by technological progress, and countries should jointly formulate a global legal framework to combat the use of deep fake technology to commit crimes. Countries can jointly prevent crimes through information sharing, joint law enforcement and other means. International cooperation can also promote technology companies to collaborate in the development and deployment of deep fake content detection tools, which can help governments and online platforms identify and delete bad content more quickly and prevent the large-scale spread of false information and malicious content.

International cooperation should not be limited to the government level. Technology companies and international non-governmental organizations can also play an active role in it through cross-border technical support and social publicity activities to promote public awareness of the harm of deep fake technology and prevent the abuse of such technology. South Korea's experience in combating gendered digital crimes is also of certain reference value, such as clearly defining the illegal use of deep fake technology through legislation and strengthening the fight against gender-based violence on the Internet. The South Korean government and social organizations have also made many plans to raise public awareness and build a support network for victims, such as community science popularization and lectures.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the widespread use of deepfake technology in cyberspace has brought about technological innovations, but also revealed a series of serious social problems, especially gendered digital violence against women. Due to the high fidelity of deepfake technology, women face greater privacy violations, reputation damage and psychological trauma. The generation and dissemination of deepfake videos often objectify and commercialize the image of women, deepening the gender discrimination and objectification of women in society. In this context, women's digital identities are severely restricted by cultural and social norms, especially in some societies that are deeply influenced by traditional gender roles, such as South Korea. When women suffer digital violence caused by deepfake technology, they are more likely to be blamed and marginalized by society. In order to effectively deal with gendered digital crimes caused by deepfake technology, cooperation between the government and social organizations is essential. By legislating to prohibit the production and dissemination of deepfake content without consent and strengthening digital privacy protection, social organizations can help victims resume their lives by raising public awareness and providing legal and psychological support. At the educational level, by deepening education on gender equality and digital privacy, it is possible to establish correct values and awareness of prevention for the younger generation, thereby reducing the harm caused by deepfake technology to women.

However, this article also has limitations. This study focuses on the case of South Korea and may not fully reflect the impact of deepfake technology on women worldwide. Future research can expand the comparative study of the application and impact of deepfake technology in different countries and cultural backgrounds.

References

[1]. Westerlund, M. (2019). The emergence of deepfake technology: A review. Technology Innovation Management Review, 9(11).

[2]. Paris, B. (2021). Configuring fakes: Digitized bodies, the politics of evidence, and agency. Social Media + Society, 7(4), 20563051211062919. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211062919

[3]. Laffier, J., & Rehman, A. (2023). Deepfakes and harm to women. Journal of Digital Life and Learning, 3(1), 1-21.

[4]. Kamberidou, I., & Pascall, N. (2019). The digital skills crisis: Engendering technology—empowering women in cyberspace. European Journal of Social Sciences Studies. https://doi.org/10.46833/ejsss.2019.01.003

[5]. Kim, H. R. (2023). The current state and legal issues of online crimes related to children and adolescents. Journal of the Korean Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(4), 222.

[6]. Securityhero. (2024). 2023 state of deepfakes. Retrieved from https://www.securityhero.io/state-of-deepfakes/

[7]. Whyte, C. (2020). Deepfake news: AI-enabled disinformation as a multi-level public policy challenge. Journal of Cyber Policy, 5(2), 199-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/23738871.2020.1778342

[8]. Cochran, J. D., & Napshin, S. A. (2021). Deepfakes: Awareness, concerns, and platform accountability. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(3), 164-172. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0225

Cite this article

Cheng,X. (2024). The Gendered Impact of Deepfake Technology: Analyzing Digital Violence Against Women in South Korea. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,75,80-85.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Westerlund, M. (2019). The emergence of deepfake technology: A review. Technology Innovation Management Review, 9(11).

[2]. Paris, B. (2021). Configuring fakes: Digitized bodies, the politics of evidence, and agency. Social Media + Society, 7(4), 20563051211062919. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211062919

[3]. Laffier, J., & Rehman, A. (2023). Deepfakes and harm to women. Journal of Digital Life and Learning, 3(1), 1-21.

[4]. Kamberidou, I., & Pascall, N. (2019). The digital skills crisis: Engendering technology—empowering women in cyberspace. European Journal of Social Sciences Studies. https://doi.org/10.46833/ejsss.2019.01.003

[5]. Kim, H. R. (2023). The current state and legal issues of online crimes related to children and adolescents. Journal of the Korean Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(4), 222.

[6]. Securityhero. (2024). 2023 state of deepfakes. Retrieved from https://www.securityhero.io/state-of-deepfakes/

[7]. Whyte, C. (2020). Deepfake news: AI-enabled disinformation as a multi-level public policy challenge. Journal of Cyber Policy, 5(2), 199-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/23738871.2020.1778342

[8]. Cochran, J. D., & Napshin, S. A. (2021). Deepfakes: Awareness, concerns, and platform accountability. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(3), 164-172. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0225