1. Introduction

Globalization has promoted world integration while bringing some challenges, leading to transnational pressure. The concept of "transnational pressure" is best understood within the framework of globalization, wherein actions, influences, or forces that transcend national boundaries impact individuals, organizations, and governments. This phenomenon frequently entails interactions among entities from diverse countries and can manifest across various domains such as politics, economics, social issues, and environmental challenges.

Africa is rich in human technological achievements, but due to the long-term colonial oppression and national liberation movements of the West in modern times, Africa fell into a long-term economic recession, a serious brain drain in science and technology, and difficulties in educational development. According to the UNESCO Science Report 2015, sub-Saharan Africa has fewer than 92 scientific researchers per million inhabitants. The brain drain has exacerbated the science and technology gap between Africa and the rest of the world, resulting in a significant shortfall in Africa's science and technology capacity building, inadequate government investment in engineering skills development, antiquated curricula and teaching methods, and skills shortages in the workforce [1].

However, reform and development can not be completed overnight, and South Africa's education system is currently facing many practical problems. For example, the discrimination caused by the history of racial segregation affects the distribution of teaching resources and leads to the decentralization of education [2]. The teaching content is biased to the theory and textbook knowledge, which is not properly connected with the real needs and is not systematic. The lack of teacher resources, the speed of teacher training and replenishment seriously lag behind the growth rate of students, and the quality of teachers is low; Poor teaching facilities further limit the development of education in Africa, and the spread of modern computer equipment is far from reach.

If these problems are left unaddressed and unchecked, these educational inequalities will be reflected in society, further exacerbating social inequalities and hampering development processes across Africa. Therefore, this paper aims to analyze the phenomena and causes of educational stress in sub-Saharan countries and make constructive educational policy recommendations with reference to the practice of Finland in developed countries.

2. Status of Sub-Saharan African Countries

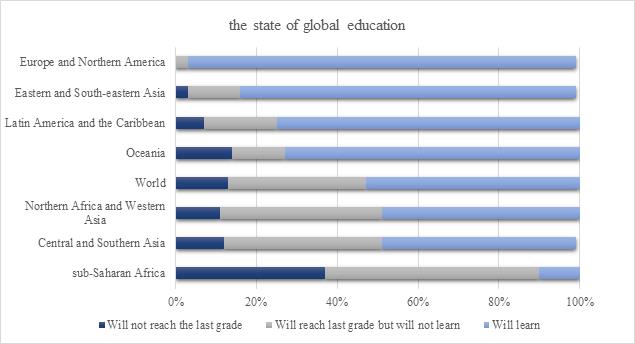

Figure 1 allows for a general classification of the state of education worldwide into regions that perform above and below the global average. Regions that perform above the global average include Europe and Northern America, Eastern and South-eastern Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as Oceania. The educational level in these regions is relatively higher. Conversely, regions performing below the global average include Northern Africa and Western Asia, Central and Southern Asia, as well as sub-Saharan Africa, all of which face significant educational challenges. Among them, the educational situations in Northern Africa and Western Asia, Central and Southern Asia are similar, with a substantial proportion of students unable to reach the last grade of schooling. Of those who do complete their education, a large percentage fail to acquire adequate knowledge. Sub-Saharan Africa is notable for having the most severe obstacles in the field of education. Approximately 40% of students in the region do not reach the last grade. And of those who do complete their studies, most do not acquire sufficient knowledge. The proportion of students who actually learn meaningful knowledge is very low, at only about 10%. This shows the region faces the huge challenges in terms of coverage of the education system and quality of education.

Based on Figure 1, there are two main reasons why sub-Saharan Africa is the focus of this study. Firstly, sub-Saharan Africa is a typical region facing severe shortages in educational resources, as the educational pressure in this region is among the most intense globally. This is reflected not only in school completion rates but also in educational quality and learning outcomes, highlighting extreme inequalities when compared with other regions. Secondly, the educational pressures in sub-Saharan Africa are influenced by multiple factors, including economic poverty, poor governance, inadequate infrastructure, and ongoing conflicts. These complex factors present obstacles to solving the region’s educational problems, but they also make sub-Saharan Africa a common case for studying the issue of unequal distribution of educational resources. Understanding these factors provides a more comprehensive perspective for analyzing the causes of global educational inequality.

Figure 1: The state of global education [3].

3. Educational Pressure and Social Inequalities in Sub-Saharan Africa

3.1. Teacher Shortages and Declining Quality of Education

Sub-Saharan Africa has faced a significant shortage of teachers for many years, with projections indicating that 15 million additional teachers will be needed by 2030 to meet rising demands [4]. This shortage is most prominent in rural and remote areas where recruiting qualified teachers is a persistent challenge. While increasing the number of teachers is vital, improving the quality of existing teachers through more robust professional development programs could also help mitigate the impact of the shortage. Teachers who are better trained can provide more effective instruction even in under-resourced environments. Additionally, improving working conditions and compensation is essential to reducing teacher turnover and ensuring that teachers remain motivated [5]. Without addressing these underlying issues, it will be difficult for education systems in Sub-Saharan Africa to keep up with the rising standards set by globalization.

3.2. The Unequal of Educational Resources in Sub-Saharan Africa

In many schools across Sub-Saharan Africa, teaching materials such as textbooks are in short supply, particularly at the primary education level. Limited funding and unequal resource distribution mean that students often share textbooks, and some schools lack basic learning tools altogether [6]. However, focusing solely on increasing the availability of physical resources might not be the only solution. One alternative is leveraging technology to supplement the lack of textbooks. Some countries have introduced electronic learning platforms and digital resources to address these gaps, but these innovations are hampered by infrastructure challenges such as unreliable electricity and poor internet connectivity. Therefore, while technology has potential, significant investments are needed to make this a viable solution in underserved areas.

3.3. Inadequate Training and Ineffective Education Systems

A lack of adequate teacher training is another issue affecting the quality of education in Sub-Saharan Africa. While many governments recognize the importance of training, in practice, these programs often fall short due to poor funding or mismanagement. Moreover, many training programs do not address the specific needs of local communities, leaving teachers ill-prepared to manage large classes or students with diverse needs [7]. Future programs should be more tailored to the specific challenges teachers face, such as addressing local cultural or linguistic differences. Additionally, introducing online or remote professional development programs could help provide ongoing training, especially for teachers in remote areas who might not have access to traditional training methods.

3.4. Low Education Completion Rates and Increasing Social Inequality

Low completion rates in Sub-Saharan Africa are often attributed to factors such as teacher shortages and a lack of learning materials. However, the issue is more complex and involves social and cultural factors as well. For instance, in many communities, gender inequality and early marriage disproportionately affect girls’ ability to complete their education. Solving these challenges requires more than just improving school conditions—it also requires addressing these societal issues through community engagement and cultural change. Governments and international organizations must work closely with local communities to create educational programs that fit their specific needs while promoting values that encourage higher completion rates [8]. In this way, education can not only reduce inequality but also promote broader societal change.

4. Reasons for the Lack of Educational Resources in Sub-Saharan Africa

The unequal of educational resources in sub-Saharan Africa is influenced by many factors.

In terms of geography, sub-Saharan Africa is a region of vast plateaus, mountains, and tropical jungles. Deep in these areas, transportation is inconvenient, teaching materials are difficult to transport, and teachers rarely choose to teach in such places. At the same time, even if there are advanced teaching facilities, it is difficult to operate because of the lack of power resources there.

In terms of economy, many countries in sub-Saharan Africa have poor economies and low government revenues. They need to invest more money to solve the problem of food and clothing for the people, and strengthen the construction of health care. Less money has been spent on education. At the same time, individual families are not rich, many parents let their children go to work to earn money, rather than let them go to school. In addition, tuition fees, books and other educational expenses are also unaffordable for many families.

In terms of social factors, sub-Saharan Africa is often the scene of violent conflict. Many families have been displaced, making it impossible to have a stable school environment. There have even been deliberate attacks on schools in West and Central Africa. Between 2015 and 2019, there were 100 attacks on schools in Nigeria, and the number of such attacks increased in the following two years, leading to the closure of schools by state governments in the northwest and northeast regions of Nigeria [9].

In terms of demographic factors, sub-Saharan Africa's population is growing rapidly, and there are few universities in Africa, which means that elite children with high grades and wealthy families have the best chance of getting a higher education. For the poor kids, it's hard to get into college. In addition, there are not enough teachers in college. One college teacher is responsible for many students. The high growth in enrolment due to population growth has led to high student/teacher ratios and crowded lecture halls with the number of students per lecturer rising by 0.5 times [10].

5. Suggestions for Improvement

From a global perspective, first, developed countries and international organizations can provide certain financial assistance to sub-Saharan Africa to help them build schools and so on. Second, they can also send education experts and volunteers to sub-Saharan Africa to conduct teacher training, improve teachers' teaching standards and share teaching methods. Third, multinational enterprises can cooperate with local governments to provide some educational technology equipment, so that students can get some high-quality educational resources from all over the world through the Internet.

From within sub-Saharan Africa, there are lessons to be learned from Finland. First, the government should pay more attention to education, increase the investment in education funds, and strengthen infrastructure development. Second, the government should strengthen teacher training, organize teachers to attend seminars and professional training courses on a regular basis, and at the same time improve the remuneration of teachers to attract more outstanding talents to engage in education. Third, the government should promote the reform of the education system, improve the quality of education, increase educational support to remote and backward areas, and strive to ensure that every child can get a fair educational opportunity. Evidence from some reviews suggests that interventions covering infrastructure (such as schools and electricity), teachers and teaching aids generally provide practical and successful assistance to education [11].

6. Conclusion

Through this research, it has been discovered that the cause for the relatively backward education in sub-Saharan African countries compared to regions such as Europe and North America is the unequal distribution of educational resources. This is mainly reflected in the shortage of teachers and low educational quality, the scarcity of teaching materials and students' insufficient learning ability, inadequate training and ineffective educational systems, low education completion rates and the intensification of social inequality, etc. Improving educational inequality in South African countries is a persistent process. The reform of the education system cannot be accomplished within a few years and requires joint efforts both internationally and domestically. Hence, this research specifically puts forward the following suggestions: Internationally, developed countries should provide financial assistance, teacher training, and technical equipment to South African countries, support cooperation between multinational enterprises and governments, and offer high-quality educational resources. Domestically, beneficial experiences should be drawn from Finland to strengthen the construction of educational infrastructure, attract talents to engage in educational work, and promote educational system reforms, etc., enabling children and adolescents of all ages to receive education and enhance the overall quality of the entire population in South African countries.

Authors Contribution

All the authors contributed equally and their names were listed in alphabetical order.

References

[1]. Huang, X., & Huang, C. (2024). History and current situation of science education development in Africa. Science and Technology Education in China, 05, 10–14.

[2]. Tang, S. (2022). Research on Inclusive Education Policy in New South Africa. Master Thesis, Zhejiang Normal University. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.27464/d.cnki.gzsfu.2022.000036doi:10.27464/d.cnki.gzsfu.2022.000036.

[3]. UNESCO. (2023). Learning outcomes. Global Education Monitoring Report. https://www.education-progress.org/zh/articles/learning

[4]. UNESCO. (2021). The persistent teacher gap in sub-Saharan Africa is jeopardizing education recovery. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org

[5]. Tikly, L. (2021). Education for Sustainable Development in Africa: Towards a Transformative Approach. Routledge.

[6]. World Bank. (2018). Facing forward:Schooling for learning in Africa. World Bank Group.

[7]. Majgaard, K., & Mingat, A. (2012). Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Comparative Analysis. World Bank Publications.

[8]. World Bank. (2018). Learning to Realize Education’s Promise. World Bank Group.

[9]. Osasona, T. (2022). Attack on Schools in Nigeria: the Crime-terror nexus. on Terrorism, 31.

[10]. Amin, A. A., & Ntembe, A. (2021). Sub-Sahara Africa's Higher Education: Financing, Growth, and Employment. International Journal of Higher Education, 10(1), 14-23.

[11]. Hassan, E., Groot, W., & Volante, L. (2022). Education funding and learning outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review of reviews. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 3, 100181.

Cite this article

Cui,J.;Fang,Q.;Ji,X.;Lin,Y. (2024). Education and Pressure in Learning in an Unequal World -- Take Sub-Saharan African Countries as an Example. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,75,147-152.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Global Politics and Socio-Humanities

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Huang, X., & Huang, C. (2024). History and current situation of science education development in Africa. Science and Technology Education in China, 05, 10–14.

[2]. Tang, S. (2022). Research on Inclusive Education Policy in New South Africa. Master Thesis, Zhejiang Normal University. https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.27464/d.cnki.gzsfu.2022.000036doi:10.27464/d.cnki.gzsfu.2022.000036.

[3]. UNESCO. (2023). Learning outcomes. Global Education Monitoring Report. https://www.education-progress.org/zh/articles/learning

[4]. UNESCO. (2021). The persistent teacher gap in sub-Saharan Africa is jeopardizing education recovery. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org

[5]. Tikly, L. (2021). Education for Sustainable Development in Africa: Towards a Transformative Approach. Routledge.

[6]. World Bank. (2018). Facing forward:Schooling for learning in Africa. World Bank Group.

[7]. Majgaard, K., & Mingat, A. (2012). Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Comparative Analysis. World Bank Publications.

[8]. World Bank. (2018). Learning to Realize Education’s Promise. World Bank Group.

[9]. Osasona, T. (2022). Attack on Schools in Nigeria: the Crime-terror nexus. on Terrorism, 31.

[10]. Amin, A. A., & Ntembe, A. (2021). Sub-Sahara Africa's Higher Education: Financing, Growth, and Employment. International Journal of Higher Education, 10(1), 14-23.

[11]. Hassan, E., Groot, W., & Volante, L. (2022). Education funding and learning outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review of reviews. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 3, 100181.