1. Introduction

Civic engagement in the selection, administration, and preservation of heritage is increasingly regarded as one of the most effective methods for advancing heritage development, and the practices of civil engagement have garnered significant attention. This is due to the fact that heritage now extends beyond the mere preservation of individual monuments but is intricately connected to several values, including history, aesthetics, culture, society, and urban life, resulting in a multi-faceted and dynamic collective evolution [1]. Citizens, as stakeholders with significant connections to heritage, possess varied perceptions and requirements to enable their involvement to effectively foster the dynamic evolution of heritage and the sustainability of its multifaceted values [2].

UNESCO endorsed The HUL Recommendation in 2011, which outlined the fundamental developmental trajectory for practical tools for civic engagement, further solidifying it as a pivotal element for the future advancement of heritage. However, we must not overlook the two significant challenges that constrain the effective scope of contemporary civic engagement. This includes the longstanding criticism of power disparities in heritage management and the difficulties in formulating coherent local heritage development objectives, which arise from potential conflicts when diverse stakeholders hold varying values and requirements concerning heritage. Therefore, in order to address these two obstacles and enhance the efficacy of civic participation in heritage development, it is essential to conduct additional research and promote existing civic engagement practices.

Two major impediments constrain the efficacy of civic engagement in heritage development. On the one hand, despite The HUL Recommendation acknowledging the importance of civic engagement and carrying the commitment to foster it, the criticism regarding disparate power dynamics in heritage management that restrict civic engagement still persists. The HUL approach primarily functions as a tool for multidisciplinary heritage management without challenging any current heritage policies. Consequently, many critical studies opt to bypass the appealing commitment of the HUL and concentrate instead on current heritage policy, particularly on the local implementation process. These studies first critique the official heritage agencies that dominate at the global level, arguing that Western elite experts still control the heritage decision-making process, thereby limiting its dynamic development [3].

Moreover, there is also oppression by national values to sub-national values (from local communities or indigenous peoples) at the national level regarding the perception of heritage and identity [4]. On the other hand, a further obstacle lies in the potential for substantial disparities in the recognition of heritage development objectives among different groups of citizens. According to Van der Aa, ‘Each individual ascribes different values... [and] will compose his or her own favourite heritage list’ [5]. This notion is especially important when we consider that heritage is closely connected with the lives, memories, cultural histories, identities, or religious views of citizens; it must also strive to address disagreements and controversies within the community to prevent civic engagement from being disrupted by possible internal conflicts.

Given the current challenges, the advancement of civic engagement practices must empower citizens and foster communication among diverse stakeholders, as indicated by the HUL Recommendation [1]. As an effective method of civic engagement nowadays, narrating the civic personal heritage stories will enable the implementation of these development visions for civic engagement. There are diverse narrative methods, such as digital heritage storytelling websites, online social groups for story sharing, and interactive heritage story maps. Silberman and Purser assert that these diverse narrative methods illustrate ‘participatory heritage praxis quite distinct from the older, static conceptions of heritage... from the forces of change’ [6]. This paper collectively designates these narrative practices as civic heritage narratives (CHN) and contends that CHN encompasses two narrative dimensions: empowerment narratives and enlightenment narratives, which can be employed to mitigate or address unequal power structures in heritage management and conflicts stemming from varied heritage perceptions.

On the one hand, the empowerment narrative can articulate the heritage perspectives of underrepresented groups to enhance their position in heritage management, as facilitating these civic stories will empower residents to challenge or address the prevailing heritage perceptions shaped by mainstream narratives [7]. On the other hand, the creation of an enlightenment narrative in CHN will stimulate a dialogue that allows different stakeholders to achieve a potential common vision, therefore, dynamically advancing the concept of heritage through fluid negotiations. As Craven expressed while developing CHORUS, the proficient utilisation of narratives will offer individuals a way to inspect, surmount biases, and engage in deeper reflection [8].

This paper seeks to illustrate the significant role of citizens in heritage management and determine the importance of empowerment and enlightenment in CHN and their efficacy in addressing the aforementioned issues via the literature review. This will encompass a thorough analysis of secondary sources, including official heritage documents, existing research pertaining to heritage and narratives, and case studies of particular local heritage practices. This paper ultimately presents the collaborative framework for the civic heritage narrative cycle to actualise the ambition of the HUL about civic engagement, serving as a practical tool for future planners and scholars in conducting CHN to promote heritage’s ability to remain active and develop further within an equally engaged conversation between different stakeholders.

2. Transformation of the Role of Citizens in Heritage Development

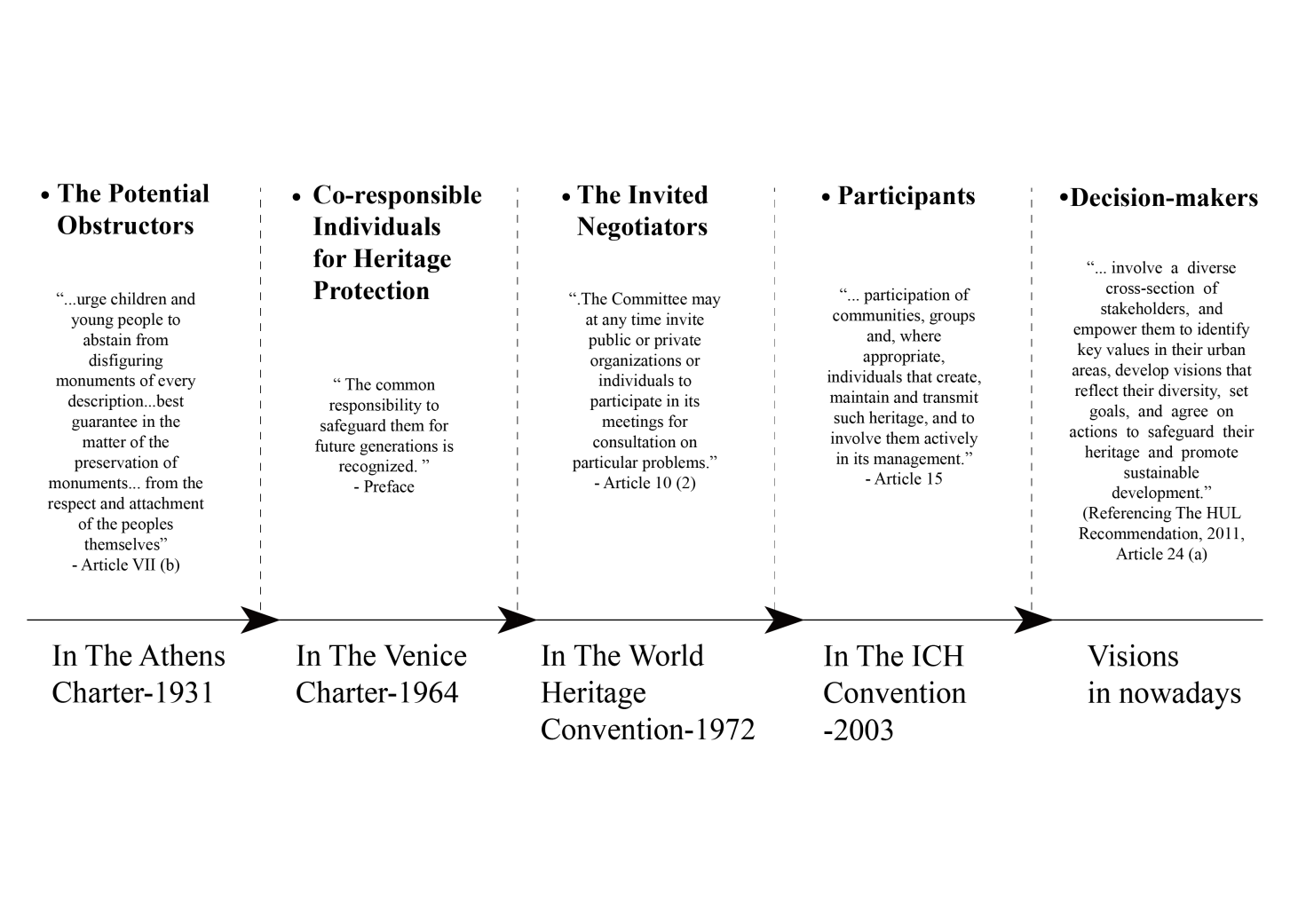

Within various historical global heritage texts, citizens have gradually transformed into potential obstructors, co-responsible individuals, invited negotiators, participants, and, recently, decision-makers (see Figure 1). This role change is attributed to the expanding notion of heritage, which increasingly incorporates citizens and fosters a positive process of democratisation [9]. This is especially true when heritage is perceived as a dynamic cultural practice with a value which is ingrained in or shaped by the process of comprehending and constructing it [10]. There is a growing recognition that the significance of heritage fluctuates with the requirements of local stakeholders. Hence, the discussion of empowerment and enlightenment in CHN is grounded in this democratic heritage process that recognises citizens as pivotal decision-makers and underscores the necessity of civic engagement in heritage management.

Figure 1: Changes in the role of citizens in different stages of heritage development.

• The potential obstructors of monument preservation (1931)

The early heritage doctrines of the 1900s emphasised the preservation of the original appearance of individual monuments. Consequently, specialists - as devout custodians - dominated the management and protection of heritage with science and technology. Citizens were perceived as ‘potential obstructors’ during this process. In the 1931 Athens Charter, the emphasis was on monuments and not ‘heritage’ [11] and the International Organization for Restoration, formed by architects and technicians, had already been the primary authority in decision-making. This significantly impacted the subsequent formal regulations for heritage recognition and protection. Citizens from the charter were instead considered to need to be educated in order to reduce damage to monuments and for the protection work to be carried out unimpeded [11]. The dominant heritage paradigm of the period resulted in this distribution of roles, which posited that the material proof of heritage dictated its entire value and demanded comprehensive protection from professionals. This originates from old Western customs as Christians esteemed and safeguarded sacred relics, utilising the tangible authenticity of legacy to understand the past [12]; this formulation solidified the early ideology of heritage perception and completely isolated it from civic participation.

• The co-responsible individuals of heritage protection (1964)

The Venice Charter of 1964 defined ‘heritage’ and prioritised the conservation of monuments as a common heritage for future generations [13]. The charter only briefly included citizens as ‘co-responsible individuals’ for heritage protection, but without involving them in specific heritage practices. As the derivative product of the Athens Charter, the Venice Charter recognised the evolving dimensions of heritage by broadening the focus beyond extraordinary artistic value to encompass ordinary works of cultural significance. Nevertheless, it continued to regard the authenticity of heritage - the original physical surface and structure - as material evidence that attests to the past [12]. Consequently, the Charter continued to emphasise the use of professional research and technology to ensure the enduring preservation of heritage objects as its primary focus, thereby reaffirming the pre-eminence of specialists in the heritage sector. Meanwhile, although the concept of ‘public engagement’ emerged after 1960 as a means of changing urban politics [14], it did not impact the framework of heritage practice or the role of citizens in the Charter during this period. Furthermore, the preamble to the Charter asserted that the principles of heritage conservation must be established internationally and executed by the state, thereby establishing the basis for subsequent global heritage organisations and the decision-making authority of the contracting parties in heritage management practices.

• Cultural heritage and the invited negotiators (1972)

As heritage gained recognition of cultural significance, it increasingly engaged citizens in management due to the initial intersection with the concept of cultural rights covered by the early human rights statutes. At the World Heritage Convention in 1972, UNESCO defined ‘cultural heritage’ as the association of diverse tangible heritage (monuments, groups of buildings, and sites) with cultural values, while also incorporating historical, artistic, and scientific values as the universal values of cultural heritage [15]. With this definition, the heritage field could potentially connect with the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). As the Declaration asserts in Article 27, every individual has the right to participate in cultural life, appreciate the arts, and contribute to scientific progress [16]. Despite the absence of references to the UDHR in the internal interpretation of the convention, the perceived correlation between the concepts of parallel development has still influenced heritage practice [17]. Hence, as the convention states, public and private institutions, as well as individuals, would be invited to provide input on ‘specific issues’ [15], which can be considered as suggesting the acknowledgement of the cultural rights of citizens. Nevertheless, the convention did not specify the extent of the ‘special problems’ or the consultation processes, nor did it address citizen engagement further. Consequently, in the mainstream heritage discourse at that stage, the responsibility of citizens remains to comply with the officially identified heritage and the rules of heritage protection. With the unclear statement of ‘invited’ and ‘specific issues,’ citizens were not expected to substantially affect the selection of heritage. Therefore, this has significantly stimulated the criticism of cultural heritage. This is largely due to culture being a heterogeneous, intangible concept rooted in the identity, values, and essence of various people, making it challenging to describe it by universal values established by experts and objective science [18]. Hence, the objectified citizen in the convention as the ambiguous ‘invited negotiator’ exemplifies the hegemonic governance of heritage and the intricacies of overlooked cultures and broader cultural proprietors [19].

• Intangible cultural heritage and the participants (2003)

The continuous emphasis on culture resulted in an evolution of heritage notions in the 1990s, along with a corresponding transformation in the role of citizens. The 1994 Nara Document on Authenticity partly broadened the spectrum of heritage conservation principles by contesting the traditional Western emphasis on material significance, drawing from East Asian cultural perspectives. Concurrently, the safeguarding of cultural variety emerged as a central concern in the domain of heritage. Logan posits that it was ‘due to fears that globalisation is antithetical to the survival of cultural diversity’ [20]. Consequently, the Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity (UDCD) of 2002 and the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH Convention) of 2003 further broadened the dimensions of culture and cultural heritage with the focus of cultural diversity and also expressly associated heritage management with human rights. The UDCD encompassed culture with lifestyles, value systems, customs, and beliefs [21], and the ICH Convention further classified them as intangible cultural heritage, encompassing the practices, knowledge, skills, and instruments, artefacts, or living spaces linked to them that are belonging to communities, organisations, or people [22]. Consequently, after the heritage category incorporated these more human-centric and varied interpretations of heritage, both of them clearly reference the prior human rights charter as the foundation of heritage management. The ICH Convention specifically acknowledged the significant involvement of communities, groups, and individuals associated with heritage and advocated for active participation in management [22]. For the first time, citizens were explicitly included as ‘participants’ in the management practices of heritage.

• The criticism of the ICH convention, and developing decision-makers (Nowadays)

Despite the explicit affirmation of the participation of citizens by the ICH Convention, civic engagement primarily served to populate the new list of intangible cultural heritage, rather than effectively determining heritage. This was because the convention was still based on the hierarchical classification and arbitrariness of heritage dominated by global heritage organisations and contracting governments [23]. Furthermore, Smith believed that the emergence of ICH has not shaken the previous inherent perception of heritage and the dominance of bureaucracy represented by Western elites or national governments [24]. In this case, it is more like ‘another concept to be tacked on to existing definitions’ [24]. Hence, due to the criticisms of the Convention and past statutes, citizens are provided with a new role from the diverse discussions and research on heritage nowadays. On the one hand, heritage is considered a resource carrying and expressing memory to construct individual or collective identity [25, 26]. Thus, the lack of citizen participation will result in their identity being ignored, distorted, or violated [27]. On the other hand, the emotions, stories, personal values, or visions of citizens related to heritage are also discussed and proved to be valuable elements to change the solidified recognition and promote the development of a multi-dimensional concept of heritage [9, 28]. These studies have partly constructed the basic attributes of civic engagement in the HUL, even though it is still in its early stages and lacks a clear overview of more theoretical shifts to practice [29]. However, it cannot be ignored that the HUL affirms the important role of citizens in the future stages of heritage management and development. Thus, the expectations of the role of citizens toward heritage today are based on these criticisms and the commitment of the HUL that is shifting citizens towards becoming real ‘decision-makers’.

3. The Empowerment Narrative

The role of citizens is now given a greater vision to change the solidified recognition of heritage values and promote the concept of heritage in dynamic development with diverse needs and perceptions. However, whether concerning heritage as the tool for constructing the identity and cultural symbols of the nation for affirming political legitimacy [30] or regarding it as an economic commodity of local tourism interests [31], heritage is frequently monopolised by the upper class and detached from ordinary citizens. In light of this persistent issue, empowering citizens may be the sole means to attain open public engagement in heritage management [32]. Based on this, advancing the development of CHN to enhance its empowerment narrative can serve as an effective means. As Sandercock described, ‘Stories and storytelling can be potent instruments or facilitators in the pursuit of change’ [33].

3.1. The Empowerment of Narrative

Examining the empowerment of narrative aims not only to view narratives as a contested resource, similar to heritage, but also to challenge and refute the prevailing circumstances surrounding heritage narratives. Rappaport referenced the 1989 notion of empowerment by the Cornell Empowerment Group as the basic assertion that narrative practice serves as a means to facilitate empowered action [34]. Empowerment is a community-centred approach that aims to assist marginalised individuals in reclaiming and managing access to resources [35]. This approach aligns with the emphasis on civic engagement for re-managing heritage resources due to existing problems, as previously discussed. A further clarification is that narratives are seen as one of the resources equitably allocated and administered under empowerment programs; that is, they serve as a symbolic resource for the formation of identity, social cognition, and the psychological sense of community [34].

Based on that, Rappaport demonstrates that issues of oppression and disenfranchisement are within narratives and that the narratives of outsiders will be disregarded or undervalued [34]. This situation is reflected in the field of heritage, where Smith promoted the AHD concept to critique the mainstream heritage discourse of recent decades [10]. Specifically, the mainstream narrative or description of heritage has isolated the perceptions or stories of citizens’ heritage. However, the ancient myths and heroic narratives have demonstrated, centuries ago, how meticulously planned narratives of archaeology can fulfil political objectives [36]. The legacy narratives of medieval Rome demonstrate how sacred ‘saintly legends’ have redefined the significance of heritage to reinforce papal authority by integrating these narratives into the urban landscape and gradually modifying public memory [37]. Furthermore, the identical issue is not exclusive to the Western environment emphasised by AHD; it is also present in Asian nations.

The research from Logan on Myanmar and its capital, Yangon, indicates that the official narrative embodying national values conflicts with local counter-narratives reflecting sub-national values. Local voices are frequently overlooked and marginalised by top-down governance due to limited funding and support, compounded by military regimes at the national level [20, 4]. Consequently, in the ongoing development of heritage, the analytical lens offered by AHD can be employed to consider narratives as a subset resource under the current competition for heritage resources. The private narratives concerning heritage are always limited, predominantly overlooked by formal institutions, and infrequently employed to enhance heritage interpretation. Consequently, as Harvey asserts, ‘heritage is not given, it is made’ [37]. In heritage management, employing narrative as a means to empower communities and citizens serves to further enable individuals to ‘create’ heritage upon mastering narrative resources.

3.2. Basic Practical Visions of Empowerment Narrative

Following the elucidation of the importance of narrative in empowering citizens, its practical aspects require additional examination. Certain action-oriented perspectives need to be evaluated to establish a theoretical foundation for the future development of CHN. The empowerment narrative primarily concentrates on the power dynamics of the narrators and the effective dimensions involved in recounting pertinent heritage stories. Van der Hoeven posited that the emphasis of citizens on diverse heritage forms primarily derives from three values, as determined by a qualitative content examination of many heritage stories of citizens from different websites that involve civic engagement [28]. These encompass experiential value, social value, and historical worth, and they offer a fundamental guideline for this research as these values embody a distinct interpretation of heritage from the viewpoint of citizens.

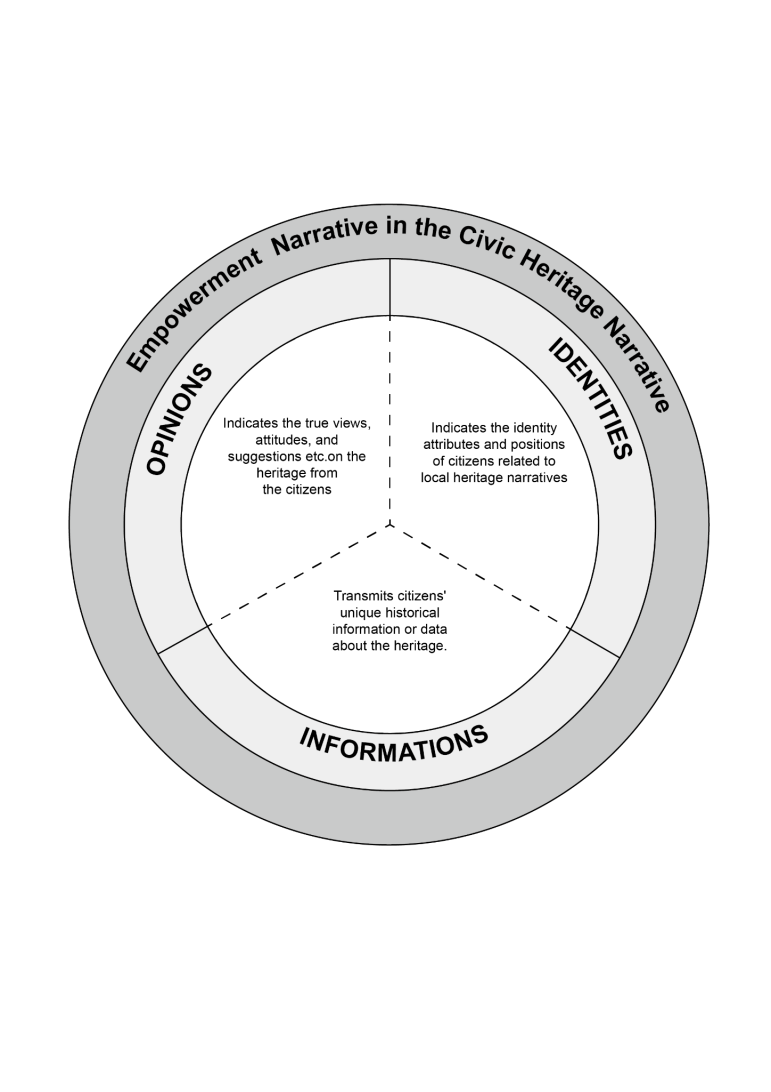

Hence, the proper employment of these values in the empowerment narrative will be to establish the important identity of citizens in determining heritage. Moreover, the inclusion of additional theoretical studies, local heritage narrative case studies, and existing CHN cases further substantiate the fundamental validity of these values for consideration. Based on these, this study suggests three basic practical visions to promote an empowerment narrative in CHN, encompassing opinions, identities, and information (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Model of the three visions of conducting the empowerment narrative in CHN.

• Opinions

As emphasised in the HUL Recommendation, it is important to understand the needs of the community to identify shared goals for heritage development. Therefore, this constructs a fundamental practical vision for the empowerment narrative, which highlights the genuine opinions of citizens on heritage. As Rappaport notes, ‘listening to and respecting individuals’ life stories inherently alters the dynamics of the relationship’ [34]. Hence, the main objective of presenting the opinions of citizens is to foster an environment of equitable dialogue that is audible. Moreover, these opinions embody the experiential value of heritage, shaped and infused with significant personal meaning through expressions of various and true emotions, memories, opinions, and experiences of local inhabitants toward heritage [28]. Thus for the empowerment narrative, regardless of the accuracy of impressions of heritage from citizens, these positive, nostalgic, frustrated, or radical opinions represent the genuine voices regarding heritage. They ought to be displayed. Ultimately, these are distinctive traits belonging to their location and would not manifest elsewhere [38]. Hart and Homsy have established that CHN effectively showcases the outcomes of actively articulating the opinions of citizens in narrative practice through their community stories map project [7]. These personal narratives that reflect many opinions have enabled individuals to assert influence over the community’s heritage and values, thereby revolutionising the stereotypical views shaped by the dominant elite-driven narrative [7].

• Identities

Identities are manifested in the social value of heritage and constitute a local identity rooted in pride and a sense of belonging to a specific locale [28]. As previously discussed, heritage serves as a resource for constructing an identity, applicable to a nation, a community, or an individual. In the empowerment narrative, it is crucial to demonstrate the identification characteristics of the narrating citizen. The sense of local belonging connects identity to location, with self-definition partially reflecting specific attributes of that area [39]. Thus, the articulation of identities partially encompasses the significance of heritage within the recognition of citizens and further delineates the sovereignty over the heritage of narrators. Heritage BC has effectively articulated this in cultivating the heritage of various cultural communities in British Columbia. As the start of the Chinese Canadian Historic Places Cultural Map states:

‘Sites were nominated by the public for their importance to the Chinese Canadian community. Together, the sites help tell the story of Chinese Canadians in British Columbia, and their role in the formation of the province of British Columbia’ [40].

Thus, presenting and highlighting the identity qualities of citizens is essential in the empowerment narrative and cannot be ignored. As McDowell asserts, ‘a process that draws on the past and which is intimately related to our identity requirements in the present’ [25].

• Information

Information, as a historical value, offers a comprehensive multi-dimensional perspective on heritage history for citizens [28] and therefore contributes to the sustainable development of heritage. On the one hand, this value appears to align with the notion of ‘citizen experts,’ referring to the involvement and impact of ‘ordinary individuals’ as ‘experts in experience’ or ‘citizen scientists’ in the management processes across diverse societal domains [41]. According to van der Hoeven, moreover, the focus is mostly on delivering tangible or informational material support for the examination of historical heritage [28], which appears to be a new paradigm for historical analysis today. This is due to the fact that personal family trees, along with preserved old family objects and documents, have provided accurate and comprehensive information for historical research [42]. CHN producers, such as Marcos Echeverría Ortiz, have explicitly illustrated the significance of showcasing distinctive historical facts in alternative narratives of heritage. The narrative project of Ortiz, ‘Where We Were Safe,’ created a narrative map of the tangible and intangible heritage of salsa in New York that is unrecorded in official documentation [43]. According to Ortiz, despite the restricted data, this historical archive, established through visual materials from social media and the oral recollections of respondents, has discovered what happened in the past [43]. Although this project primarily relies on personal recollections for significant information, it’s important to recognise that these recollections provide a unique form of support for historical heritage research. As Ortiz anticipates, this project could function as an educational tool to encourage a critical re-evaluation of history [43]. Consequently, regardless of the interpretation emphasised, it underscores the capacity and influence of citizens to advocate for heritage, particularly after the contribution of citizens to historical information about heritage is shown in the empowerment narrative.

4. The Enlightenment Narrative

The empowerment narrative emphasises the authoritative role of the narrating citizen who occupies the subject position and fosters an affirmative and basic environment for civic engagement. Additionally, it is essential to acknowledge the challenges that extensive civic engagement may encounter, which is another important dimension of developing the CHN. Historically, the struggle for control over heritage has primarily focused on global heritage management institutions like UNESCO or ICOMOS, which have become the primary targets of opposition due to their potential to hinder individual empowerment. However, an alternative interpretation or critique of the AHD concept argues that it misunderstands the essence of UNESCO’s authority and the extent of its potential influence, implying that nation-states ultimately hold the capacity to innovate or suppress [44]. This reinterpretation of heritage management transitions from the top-down perspective to an alternative power structure, as the subjugation of sub-national values by national values.

However, adhering to this top-down perspective of reflection highlights that the issue also involves the exercise of autonomy within the local context. Ginzarly et al. explained how the implementation of HUL is significantly influenced by the local management framework and the level of collaboration among various stakeholders [29]. Hence, incorporating and articulating more civic values will enhance the notion of heritage, but it may also incite disputes and rivalry stemming from divergent perceptions or requirements. Achieving consensus on heritage policies or specific management methods and executing them effectively is similarly challenging. Consequently, the CHN must also contemplate the aim of narrative - specifically, the cognitive aspect of the heritage stories for the reader - to effectively harmonise diverse needs. This research highlights an additional narrative dimension that CHN should consider: the enlightenment narrative.

4.1. The Dilemma of Controversy Over Diverse Heritage Values

Conflicts among heritage actors can initially be observed within the broader international disputes. Consider the case study of Cesari & Herzfeld regarding the Palestinian-Israeli conflict over the Old City of Hebron [45]. The Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron is regarded as a significant historical and religious monument due to its housing of the tombs of biblical patriarchs, rendering it very important to both Jews and Muslims. Jewish settlers have utilised heritage to alter the disputed territory, establish sovereignty, and have sought to displace the indigenous Palestinian community from their homes and heritage through pilgrimages, festivals, and the reinterpretation of ethnic histories [45]. The heritage discord between the two factions is grounded in the intersecting elements of historical narratives, memories, and identities, resulting in conflicting accounts from two distinct interest groups regarding the same location and heritage site.

Beyond the context of international conflict, even minor local narratives may disagree due to varying conceptions of place, identity, values, or developmental aspirations. The investigation by Jeannotte into story mapping across three distinct communities reveals that community narratives tend to be ‘messy, non-linear, contested (even within the community), and ongoing’ [38]. Heritage management in a local area usually encompasses the interests of bureaucrats, civic organisations, multinational capital, real estate speculators, local churches, locals, and new immigrants. The new process of heritage management nowadays in modern cities, emphasising the importance of supplementary benefits, has engaged these different participants with significantly varied power dynamics and ideologies [45]. A top-down perspective based on heritage top-down management reminds us that, while developing the initiatives of empowerment, there is also a need to deal with conflicts of values among individuals. This is also an approach to heritage management from the bottom up; as the HUL approach suggests, communication and dialogue should be promoted to arrive at a shared vision. Hence, the importance of the enlightenment narrative, which aims to produce an alternative communicating environment in the CHN.

4.2. Basic Practical Visions of Enlightenment Narrative

Heritage studies rarely address the enlightenment narrative. The words might be regarded as the cultural movement in 18th-century Europe. However, as Hassard indicates, the static traditional heritage discourse in the UK, by emphasising tangible heritage, was exactly influenced by Enlightenment ideals of scientific rationalism that prioritised materiality [46]. Therefore, this paper emphasises the enlightenment narrative, which is not about any famous campaign, but rather aims to engage the reader in CHN practice and encourage an open dialogue to resolve potential conflicts. According to the definition of ‘enlightenment,’ which is defined as ‘the action of bringing someone to a state of greater knowledge, understanding, or insight’ [47], it will be helpful to further explain the purpose of narratives.

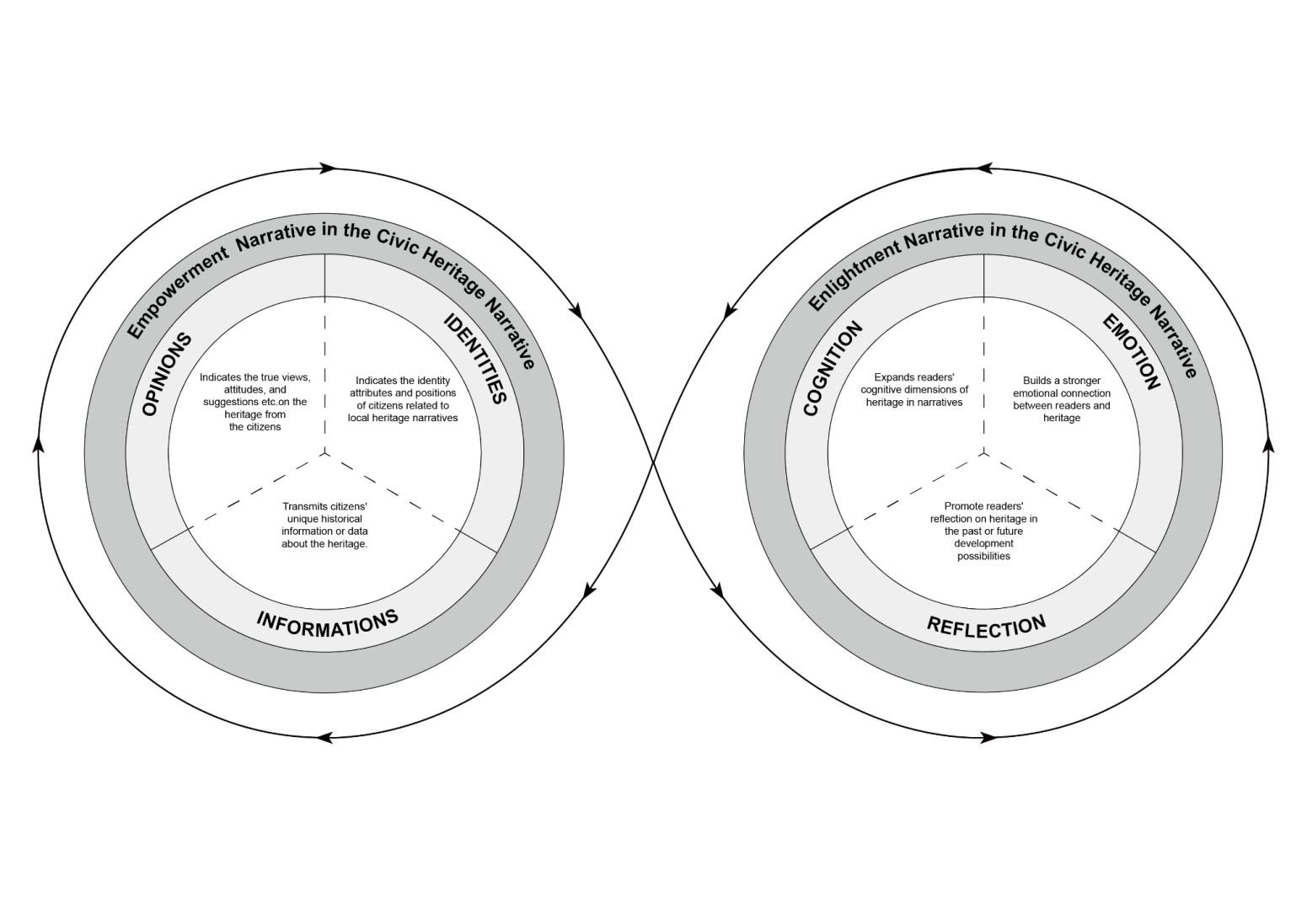

The intricate study of narrative grammatical structure by Blake and Bower posits that stories partially facilitate readers’ comprehension, reasoning, and contemplation of potential problem-solving methods [48]. Currently, several research and specific case studies of civic heritage stories have demonstrated the fundamental dimensions of crafting enlightenment narratives. Through a comprehensive review of these studies, this paper provides three basic practical visions for developing the enlightenment narrative in the CHN: cognition, emotion, and reflection (see Figure 3).

• Cognition

The first objective of the enlightenment narrative is to provide or extend the cognition of readers about the heritage in the CHN. This appears to be the essential function of the narrative, which is also applicable to the heritage narrative. The mainstream heritage narrative, as examined and critiqued by AHD, has already shaped the collective understanding of heritage through meta-narrative and abundant professional rhetoric, thereby acknowledging the static heritage defined by the dominant bureaucracy and the official heritage list. In contrast, the affordance of the enlightenment narrative, based on civic engagement, lies in how it can enable readers to gain a different understanding and awareness of heritage through the empowering personal stories of citizens. The study on social media by van der Hoeven has partially illustrated the practical application of CHN in shaping audience perception by showing how shared stories can effectively highlight heritage in an accessible manner and engage a diverse audience [49]. Therefore, when crafting the enlightenment narrative, one of the objectives should be to enhance the readers’ peripheral understanding of the heritage of the depicted location through personal accounts, thereby enriching their potential inherent notions of that heritage. This objective involves sharing Zembylas and Bekerman’s account of historical trauma in education, which calls for the establishment of environments where students can collaboratively explore the importance of bearing witness to the other [50].

• Emotion

Gregory conducted a study on a Facebook group, ‘Beautiful Old Perth,’ which exemplifies another crucial aspect of enlightenment narratives: emotional resonance [51]. Gregory posited that the objective of the study was to refute the assertion of Lowenthal that social media erodes the connection between community and historical attachment [51]. This study discovered a diverse array of personal stories, photographs, and other narrative materials, which, when combined to create a cohesive narrative about Perth, fostered an emotional community characterised by a shared emotional bond and incited a series of participatory actions among its members. This encompassed the establishment of groups, solicitations for external awareness and assistance, and public demonstrations opposing historic destruction within the community [51]. This case study proved the effectiveness of CHN in constructing the connection between community and heritage history. Moreover, it clearly illustrated the specific trajectory of individual heritage narratives in promoting civic engagement, constructing a nostalgia for a specific place, and a wider sense of shared emotion through a narrative to gain more attention from both inside and outside the area. Based on the case study of Gregory, it can be shown that there is a need to incorporate another focus in the development of enlightenment narratives, namely, the need to create a greater emotional connection between the reader and the heritage being described, in order to support greater participation in local participatory practices or discussions.

• Reflection

The last fundamental practical vision of constructing the enlightenment narrative is to provoke reflection in the readers. The construction of reflection can be seen in historical education and narrative. Haste and Bermudez present a valuable examination of studies regarding the application of historical narratives in education [52]. History education in schools can foster critical examination of the past, elucidate underlying causes, and amplify marginalised voices through storytelling as a reflective practice that naturally offers alternative interpretations for contemporary issues and inquiries [52]. Moreover, the case study of Gregory exemplifies the social production of reflection beyond the classroom. A different community linked to the social group in Perth had divergent attitudes and reactions, which ‘minimised the loss and emphasised the enduring heritage that persisted.’ Positive marketing enhanced public awareness of cultural worth; however, another segment of the population perceived heritage as ‘a valuable commodity... traded for its use’ [51]. These two works illustrate the necessity of constructing or enabling reflection on heritage with the enlightenment narrative, and the research of Gregory specifically illustrates how varying reflections shape different forms of engagement within communities. The final outcome, irrespective of its direction, is influenced by authentic civic participation and collective contemplation.

Figure 3: Model of the three visions of conducting the enlightenment narrative in CHN.

5. The Collaborative Framework of The Civic Heritage Narrative Cycle

Following the establishment of the practical visions of empowerment and enlightenment narrative, it is essential to further examine their operational relationship in practice and develop a theoretical framework to support the promotion of citizen participation and heritage development in future CHN practices. It is crucial to recognise that empowerment and enlightenment possess distinct internal focuses, yet they should maintain a collaborative relationship within the overarching narrative practice (see Figure 4). The dialogism from Mikhail Bakhtin can elucidate this scenario. Bakhtin promotes a dialogic perspective that appreciates diversity, emphasises the fluidity and interplay among many cultures, and posits culture as a product of ongoing debate [53]. Heritage, as a dynamic cultural practice, requires pluralistic dialogue to maintain the flexibility of its ideals within the civic narrative. According to Patterson, dialogism represents a contact and collision of consciousnesses that surpasses linguistic expression [54]. Hence, CHN will not just function as a unilateral activity that empowers the people narrating the story. Rather, it will be based on empowerment while also promoting the cognitive dimension of readers with the story and the related heritage to foster diverse dialogues among various backgrounds and values in multiple ways.

On the other hand, we may consider the thesis in The Democratic Paradox by Chantal Mouffe, which posits that conflicts within a democratic society can serve as a catalyst for reinforcing democracy, as pluralistic beliefs facilitate the establishment of commonality [55]. The theory of antagonistic democratic conflict is applicable to heritage disputes; it illustrates how various reasonings can be employed to establish collective identities and coordinate actions without the use of violence [56]. Furthermore, in evaluating the practice of CHN, Haskins critiqued the digital archive forum concerning the September 11th tragedy [57]. If utilised solely for the purpose of enabling ordinary individuals to share and commemorate historical events and associated memories, without fostering an environment conducive to debate, it will merely offer ‘a depoliticised surface’ and endorse ‘an atomised practice of remembrance’ [57], thereby obstructing potential discussions.

Consequently, while one objective of the enlightenment narrative may be to address the conflict dilemmas arising from widespread empowerment, it is equally important to foster ‘gentle’ disputes, channel conflict and chaos, and promote mediation to enhance civic engagement. In this case, the enlightenment narrative will provide the wider constructing elements for the potential discord through the narrative practice process.

Figure 4: The collaborative framework of the civic heritage narrative cycle.

This study offers the collaborative framework of the civic heritage narrative cycle, informed by the analysis of dialogue relationships and conflict tones. Figure 4 illustrates that when both empowerment and enlightenment narratives are simultaneously focused on and advanced, they establish an equitable cyclical relationship on the outside and externally interact with one another. Simultaneously, it must be clarified that Figure 4 presents an idealistic representation of CHN practice. The collaborative framework, influenced by varying cultural and historical contexts, local conditions, or narrative practices, may exhibit bias towards a particular perspective. However, this study contends that to realise the multifaceted utility of CHN, the fundamental cyclical interaction between the empowerment narrative and the enlightenment narrative must be preserved.

6. Conclusion

Based on the HUL’s vision of developing civic engagement tools in heritage, this study proposes a collaborative framework for the civic heritage narrative cycle. This framework supports the CHN, a category of civic engagement practices, and aids future developers and researchers in establishing a foundational reference for this practice. This collaborative framework extends beyond the perspective of focusing solely on addressing the practical challenges that impede contemporary civic engagement but also aims to enhance the advancement of CHN practices. Particularly after the introduction of the concept of ‘heritage futures,’ Holtorf argues that a widespread lack of understanding of cultural dynamics among the population currently hinders the long-term preservation of heritage [58]. This research posits that the proposed collaborative framework will enhance CHN practices by fostering an open narrative environment. This, in turn, will enable narrators and other stakeholders to express their heritage through a variety of methods, such as emphasising, discussing, arguing, and contemplating, thereby deepening their understanding of the dynamic essence of heritage. Simultaneously, it will integrate further heritage knowledge to perpetually refine the understanding and scope of heritage. New selections will be implemented or some existing recognised heritage will be discarded, guaranteeing that heritage remains prioritised, and integral to the lives of residents with genuine voices and anticipations.

Furthermore, it is essential to recognise that the collaborative framework possesses certain limits derived based on the examination that are only about parts of existing theories and case studies. Therefore, it can be viewed as a fundamental developmental tool that guides the practice of CHN. Subsequent analysis needs to concern the varying values of heritage across distinct cultural, historical, and social settings, alongside the increasingly diversified perspectives of citizens on heritage. Meanwhile, this study discusses CHN as the combination of different storytelling practices that have the same aim of civic engagement, excluding the specific discussion of the diverse narrative styles within CHN. As CHN evolves in several dimensions, especially the story maps that have emerged as a dynamic visual narrative by integrating images, videos, audio, and text [59]. This study suggests that various narrative methods can employ or examine the collaborative framework, thereby deriving additional narrative dimensions and practical visions for CHN development through diverse narrative approaches or media.

References

[1]. UNESCO. (2011) Recommendation on the historic urban landscape. https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-638-98.pdf

[2]. Jones, S. (2016) Wrestling with the Social Value of Heritage: Problems, Dilemmas and Opportunities. Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage, 4(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2016.1193996

[3]. Waterton, E. and Smith, L. (2010) The recognition and misrecognition of community heritage. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 16(1–2), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441671

[4]. Logan, W. (2016) Whose heritage? Conflicting narratives and top-down and bottom-up approaches to heritage management in Yangon, Myanmar. In S. Labadi & W. Logan (Eds.), Urban Heritage, Development and Sustainability: International Frameworks, National and Local Governance (pp. 256-273 ). Routledge.

[5]. Van der Aa, B.J.M. (2005) Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing.

[6]. Silberman and Purser (2012) Collective Memory as Affirmation: People-centered cultural heritage in a digital age. In E. Giaccardi (Ed.), Heritage and Social Media: Understanding heritage in a participatory culture (pp. 13-29). Routledge.

[7]. Hart, S.M. and Homsy, G.C. (2020) Stories from North of Main: Neighborhood Heritage Story Mapping. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 24, 950–968. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-019-00529-4

[8]. CHORUS, n.d. CHORUS: Civic Heritage and Oral History Unification System. https://solve.mit.edu/challenges/learning-for-civic-action-challenge/solutions/75303

[9]. van der Hoeven, A. (2016) Networked practices of intangible urban heritage: the changing public role of Dutch heritage professionals. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 25(2), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2016.1253686

[10]. Smith, L. (2006) Uses of Heritage (1st ed.). Routledge.

[11]. The Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments, (1931), https://www.icomos.org/en/167-the-athens-charter-for-the-restoration-of-historic-monuments

[12]. Wells J. C. (2007) The plurality of truth in culture, context, and heritage: A (mostly) post-structuralist analysis of urban conservation charters. City & Time, 3(2), 1-14. https://docs.rwu.edu/saahp_fp/19

[13]. The Venice Charter (1964) Adopted by ICOMOS in 1965, https://www.icomos.org/en/participer/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/157-the-venice-charter

[14]. Healey, P. (2008) Civic Engagement, Spatial Planning and Democracy as a Way of Life. Planning Theory & Practice, 9(3), 379-382. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350802277092

[15]. UNESCO (1972) Convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. https://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf

[16]. Universal Declaration of Human Rights (December, 10, 1948) https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

[17]. Logan, W. (2012) Cultural diversity, cultural heritage and human rights: towards heritage management as human rights-based cultural practice. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 18(3), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.637573

[18]. Hodder, I. (2010) Cultural Heritage Rights: From Ownership and Descent to Justice and Well-being. Anthropological Quarterly, 83(4), 861–882. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40890842

[19]. Byrne, D. (1991) Western hegemony in archaeological heritage management. History and Anthropology, 5(2), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.1991.9960815

[20]. Logan, W. (2007). Closing Pandora’s Box: human rights conundrums in cultural heritage protection. In: H. Silverman and D.F. Ruggles (Eds). Cultural heritage and human rights (pp. 33-52). Springer.

[21]. UNESCO (2002) Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity: a vision, a conceptual platform, a pool of ideas for implementation, a new paradigm. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000127162

[22]. UNESCO (2003) Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/15164-EN.pdf

[23]. Byrne, D. (2009) A critique of unfeeling heritage. In L. Smith & N. Akagawa (Eds.), Intangible Heritage (pp. 229-252). Routledge.

[24]. Smith, L. (2015) Intangible Heritage: A challenge to the authorised heritage discourse? Ethnologia, 40, 133-142. https://www.academia.edu/34518290/Intangible_Heritage_A_challenge_to_the_authorised_heritage_discourse

[25]. McDowell, S. (2008) Heritage, memory and identity. In B. Graham, & P. Howard (Eds.), The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity (pp. 37-54). Ashgate Publishing.

[26]. Graham, B. and Howard, P. (2008) Heritage and Identity. In B. Graham (Ed.), The Routledge Research Companion to Heritage and Identity (pp.1-9). Routledge.

[27]. Lowenthal, D. (1994) CHAPTER II. Identity, Heritage, and History. In J. Gillis (Ed.), Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity (pp. 41-58). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691186658-005

[28]. van der Hoeven, A. (2020) Valuing Urban Heritage Through Participatory Heritage Websites: Citizen Perceptions of Historic Urban Landscapes. Space and Culture, 23(2), 129-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331218797038

[29]. Ginzarly, M., Houbart, C. and Teller, J. (2018) The Historic Urban Landscape approach to urban management: a systematic review. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(10), 999–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1552615

[30]. Hall, S. (1999) Un‐settling ‘the heritage’, re‐imagining the post‐nation. Whose heritage? Third Text, 13(49), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09528829908576818

[31]. Chang, T.C. (1997) Heritage as a Tourism Commodity: Traversing the Tourist–Local Divide. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 18(1), 46-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9493.00004

[32]. Babić, D. (2015) Social Responsible Heritage Management - Empowering Citizens to Act as Heritage Managers. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 188, 27-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.335

[33]. Sandercock, L. (2003) Out of the Closet: The Importance of Stories and Storytelling in Planning Practice. Planning Theory & Practice, 4(1), 11–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935032000057209

[34]. Rappaport, J. (1995) Empowerment meets narrative: Listening to stories and creating settings. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 795–807. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02506992

[35]. Cornell Empowerment Group (1989) Empowerment and family support. Networking Bulletin, 1(2), 1-23.

[36]. Silberman, N. (1995) Promised lands and chosen peoples: the politics and poetics of archaeological narrative. In P.L. Kohl & C. Fawcett (Eds.), Nationalism, politics, and the practice of archaeology (pp.249-262). Cambridge University Press.

[37]. Harvey, D.C. (2001) Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 7(4), 319-338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13581650120105534

[38]. Jeannotte, M.S. (2016) Story-telling about place: Engaging citizens in cultural mapping. City, Culture and Society, 7(1), 35-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2015.07.004

[39]. Rose, G. (1995) Places and Identity: A Sense of Place, In D. Massey & P. Jess (Eds.), A Place in the World? Places, Cultures and Globalisation (pp.87–131). Oxford University Press

[40]. Heritage BC (n.d.) The Chinese Canadian Historic Places Cultural Map. Heritage BC, Cultural Maps. https://heritagebc.ca/cultural-maps/chinese-historic-places-map

[41]. Krick, E. and Meriluoto, T. (2022) The Advent of the Citizen Expert. Democratising or Pushing the Boundaries of Expertise?. Current Sociology, 70(7). https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921221078043

[42]. Barratt, N. (2009) From memory to digital record: Personal heritage and archive use in the twenty‐first century. Records Management Journal, (19)1, 8-15. https://doi.org/10.1108/09565690910937209

[43]. Ortiz, M.E. (2021) “Where We Were Safe”: Mapping Resilience in the 1970s Salsa Scene. The Latinx Project at New York University.https://www.latinxproject.nyu.edu/intervenxions/where-we-were-safe-mapping-resilience-in-the-1970s-salsa-scene

[44]. Askew, M. (2010) The Magic List of Global Status. In C. Long & S. Labadi (Eds.), Heritage and Globalisation (pp.19–44). Routledge.

[45]. Cesari, C.D. and Herzfeld, M. (2015) Urban Heritage and Social Movements. In L. Meskell (Ed.), Global Heritage: A Reader (pp.171-195). Wiley-Blackwell.

[46]. Hassard, F. (2008). Intangible heritage in the United Kingdom: The dark side of enlightenment? In L. Smith & N. Akagawa (Eds.), Intangible Heritage (pp. 270–288). Routledge.

[47]. Oxford University Press (n.d.) Enlightenment. In Oxford English dictionary. Retrieved October 24, 2024, from https://w55eylkejyz-s-a865.bj.tsgdht.cn/dictionary/enlightenment_n?tab=meaning_and_use#5441399

[48]. Black, J.B. and Bower, G. (1980) Story understanding as problem-solving. Poetics, 9(1), 223-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-422X(80)90021-2

[49]. van der Hoeven, A. (2019) Historic urban landscapes on social media: The contributions of online narrative practices to urban heritage conservation. City, Culture and Society, 17, 61-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2018.12.001

[50]. Zembylas, M. and Bekerman, Z. (2008) Education and the Dangerous Memories of Historical Trauma: Narratives of Pain, Narratives of Hope. Curriculum Inquiry, 38(2), 125–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2007.00403.x

[51]. Gregory, J. (2015) Connecting with the past through social media: the ‘Beautiful buildings and cool places Perth has lost’ Facebook group. International Journal of Heritage Studies, (21)1, 22-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2014.884015

[52]. Haste, H. and Bermudez, A. (2017) The Power of Story: Historical Narratives and the Construction of Civic Identity. In M. Carretero, S. Berger and M. Grever (Eds.), Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education (pp.427–447). Palgrave Macmillan London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-52908-4_23

[53]. Haye, A. and González, R. (2021) Dialogic borders: Interculturality from Vološinov and Bakhtin. Theory & Psychology, 31(5), 746-762. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354320968635

[54]. Patterson, D. (1985) Mikhail Bakhtin and the Dialogical Dimensions of the Novel. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 44(2), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.2307/430515

[55]. Mouffe, C. (2000) The Democratic Paradox. Verso Books.

[56]. Meriluoto, T.M. and Eranti, V. (2023) PLURALITY IN URBAN POLITICS: Conflict and Commonality in Mouffe and Thevenot. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 47(5), 693-709. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.13205

[57]. Haskins, E.V. (2015) Toward a Participatory Memory Culture. In Popular Memories: Commemoration, Participatory Culture, and Democratic Citizenship (pp. 117–130). University of South Carolina Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv6wghw7.11

[58]. Holtorf, C. and Bolin, A. (2024) Heritage Futures: A Conversation. Journal of Cultural Heritage. Management and Sustainable Development, 14(2), 252-265. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-09-2021-0156

[59]. Roth, R.E. (2021) Cartographic Design as Visual Storytelling: Synthesis and Review of Map-Based Narratives, Genres, and Tropes, The Cartographic Journal, 58(1), 83-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00087041.2019.1633103

Cite this article

Lang,Y. (2025). Empowerment and Enlightenment: The Practical Dimensions of Civic Heritage Narrative. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,81,26-41.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. UNESCO. (2011) Recommendation on the historic urban landscape. https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-638-98.pdf

[2]. Jones, S. (2016) Wrestling with the Social Value of Heritage: Problems, Dilemmas and Opportunities. Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage, 4(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2016.1193996

[3]. Waterton, E. and Smith, L. (2010) The recognition and misrecognition of community heritage. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 16(1–2), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441671

[4]. Logan, W. (2016) Whose heritage? Conflicting narratives and top-down and bottom-up approaches to heritage management in Yangon, Myanmar. In S. Labadi & W. Logan (Eds.), Urban Heritage, Development and Sustainability: International Frameworks, National and Local Governance (pp. 256-273 ). Routledge.

[5]. Van der Aa, B.J.M. (2005) Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing.

[6]. Silberman and Purser (2012) Collective Memory as Affirmation: People-centered cultural heritage in a digital age. In E. Giaccardi (Ed.), Heritage and Social Media: Understanding heritage in a participatory culture (pp. 13-29). Routledge.

[7]. Hart, S.M. and Homsy, G.C. (2020) Stories from North of Main: Neighborhood Heritage Story Mapping. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 24, 950–968. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-019-00529-4

[8]. CHORUS, n.d. CHORUS: Civic Heritage and Oral History Unification System. https://solve.mit.edu/challenges/learning-for-civic-action-challenge/solutions/75303

[9]. van der Hoeven, A. (2016) Networked practices of intangible urban heritage: the changing public role of Dutch heritage professionals. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 25(2), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2016.1253686

[10]. Smith, L. (2006) Uses of Heritage (1st ed.). Routledge.

[11]. The Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments, (1931), https://www.icomos.org/en/167-the-athens-charter-for-the-restoration-of-historic-monuments

[12]. Wells J. C. (2007) The plurality of truth in culture, context, and heritage: A (mostly) post-structuralist analysis of urban conservation charters. City & Time, 3(2), 1-14. https://docs.rwu.edu/saahp_fp/19

[13]. The Venice Charter (1964) Adopted by ICOMOS in 1965, https://www.icomos.org/en/participer/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/157-the-venice-charter

[14]. Healey, P. (2008) Civic Engagement, Spatial Planning and Democracy as a Way of Life. Planning Theory & Practice, 9(3), 379-382. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350802277092

[15]. UNESCO (1972) Convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. https://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf

[16]. Universal Declaration of Human Rights (December, 10, 1948) https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

[17]. Logan, W. (2012) Cultural diversity, cultural heritage and human rights: towards heritage management as human rights-based cultural practice. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 18(3), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.637573

[18]. Hodder, I. (2010) Cultural Heritage Rights: From Ownership and Descent to Justice and Well-being. Anthropological Quarterly, 83(4), 861–882. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40890842

[19]. Byrne, D. (1991) Western hegemony in archaeological heritage management. History and Anthropology, 5(2), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.1991.9960815

[20]. Logan, W. (2007). Closing Pandora’s Box: human rights conundrums in cultural heritage protection. In: H. Silverman and D.F. Ruggles (Eds). Cultural heritage and human rights (pp. 33-52). Springer.

[21]. UNESCO (2002) Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity: a vision, a conceptual platform, a pool of ideas for implementation, a new paradigm. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000127162

[22]. UNESCO (2003) Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/15164-EN.pdf

[23]. Byrne, D. (2009) A critique of unfeeling heritage. In L. Smith & N. Akagawa (Eds.), Intangible Heritage (pp. 229-252). Routledge.

[24]. Smith, L. (2015) Intangible Heritage: A challenge to the authorised heritage discourse? Ethnologia, 40, 133-142. https://www.academia.edu/34518290/Intangible_Heritage_A_challenge_to_the_authorised_heritage_discourse

[25]. McDowell, S. (2008) Heritage, memory and identity. In B. Graham, & P. Howard (Eds.), The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity (pp. 37-54). Ashgate Publishing.

[26]. Graham, B. and Howard, P. (2008) Heritage and Identity. In B. Graham (Ed.), The Routledge Research Companion to Heritage and Identity (pp.1-9). Routledge.

[27]. Lowenthal, D. (1994) CHAPTER II. Identity, Heritage, and History. In J. Gillis (Ed.), Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity (pp. 41-58). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691186658-005

[28]. van der Hoeven, A. (2020) Valuing Urban Heritage Through Participatory Heritage Websites: Citizen Perceptions of Historic Urban Landscapes. Space and Culture, 23(2), 129-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331218797038

[29]. Ginzarly, M., Houbart, C. and Teller, J. (2018) The Historic Urban Landscape approach to urban management: a systematic review. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(10), 999–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1552615

[30]. Hall, S. (1999) Un‐settling ‘the heritage’, re‐imagining the post‐nation. Whose heritage? Third Text, 13(49), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09528829908576818

[31]. Chang, T.C. (1997) Heritage as a Tourism Commodity: Traversing the Tourist–Local Divide. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 18(1), 46-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9493.00004

[32]. Babić, D. (2015) Social Responsible Heritage Management - Empowering Citizens to Act as Heritage Managers. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 188, 27-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.335

[33]. Sandercock, L. (2003) Out of the Closet: The Importance of Stories and Storytelling in Planning Practice. Planning Theory & Practice, 4(1), 11–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935032000057209

[34]. Rappaport, J. (1995) Empowerment meets narrative: Listening to stories and creating settings. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 795–807. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02506992

[35]. Cornell Empowerment Group (1989) Empowerment and family support. Networking Bulletin, 1(2), 1-23.

[36]. Silberman, N. (1995) Promised lands and chosen peoples: the politics and poetics of archaeological narrative. In P.L. Kohl & C. Fawcett (Eds.), Nationalism, politics, and the practice of archaeology (pp.249-262). Cambridge University Press.

[37]. Harvey, D.C. (2001) Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 7(4), 319-338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13581650120105534

[38]. Jeannotte, M.S. (2016) Story-telling about place: Engaging citizens in cultural mapping. City, Culture and Society, 7(1), 35-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2015.07.004

[39]. Rose, G. (1995) Places and Identity: A Sense of Place, In D. Massey & P. Jess (Eds.), A Place in the World? Places, Cultures and Globalisation (pp.87–131). Oxford University Press

[40]. Heritage BC (n.d.) The Chinese Canadian Historic Places Cultural Map. Heritage BC, Cultural Maps. https://heritagebc.ca/cultural-maps/chinese-historic-places-map

[41]. Krick, E. and Meriluoto, T. (2022) The Advent of the Citizen Expert. Democratising or Pushing the Boundaries of Expertise?. Current Sociology, 70(7). https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921221078043

[42]. Barratt, N. (2009) From memory to digital record: Personal heritage and archive use in the twenty‐first century. Records Management Journal, (19)1, 8-15. https://doi.org/10.1108/09565690910937209

[43]. Ortiz, M.E. (2021) “Where We Were Safe”: Mapping Resilience in the 1970s Salsa Scene. The Latinx Project at New York University.https://www.latinxproject.nyu.edu/intervenxions/where-we-were-safe-mapping-resilience-in-the-1970s-salsa-scene

[44]. Askew, M. (2010) The Magic List of Global Status. In C. Long & S. Labadi (Eds.), Heritage and Globalisation (pp.19–44). Routledge.

[45]. Cesari, C.D. and Herzfeld, M. (2015) Urban Heritage and Social Movements. In L. Meskell (Ed.), Global Heritage: A Reader (pp.171-195). Wiley-Blackwell.

[46]. Hassard, F. (2008). Intangible heritage in the United Kingdom: The dark side of enlightenment? In L. Smith & N. Akagawa (Eds.), Intangible Heritage (pp. 270–288). Routledge.

[47]. Oxford University Press (n.d.) Enlightenment. In Oxford English dictionary. Retrieved October 24, 2024, from https://w55eylkejyz-s-a865.bj.tsgdht.cn/dictionary/enlightenment_n?tab=meaning_and_use#5441399

[48]. Black, J.B. and Bower, G. (1980) Story understanding as problem-solving. Poetics, 9(1), 223-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-422X(80)90021-2

[49]. van der Hoeven, A. (2019) Historic urban landscapes on social media: The contributions of online narrative practices to urban heritage conservation. City, Culture and Society, 17, 61-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2018.12.001

[50]. Zembylas, M. and Bekerman, Z. (2008) Education and the Dangerous Memories of Historical Trauma: Narratives of Pain, Narratives of Hope. Curriculum Inquiry, 38(2), 125–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2007.00403.x

[51]. Gregory, J. (2015) Connecting with the past through social media: the ‘Beautiful buildings and cool places Perth has lost’ Facebook group. International Journal of Heritage Studies, (21)1, 22-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2014.884015

[52]. Haste, H. and Bermudez, A. (2017) The Power of Story: Historical Narratives and the Construction of Civic Identity. In M. Carretero, S. Berger and M. Grever (Eds.), Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education (pp.427–447). Palgrave Macmillan London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-52908-4_23

[53]. Haye, A. and González, R. (2021) Dialogic borders: Interculturality from Vološinov and Bakhtin. Theory & Psychology, 31(5), 746-762. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354320968635

[54]. Patterson, D. (1985) Mikhail Bakhtin and the Dialogical Dimensions of the Novel. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 44(2), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.2307/430515

[55]. Mouffe, C. (2000) The Democratic Paradox. Verso Books.

[56]. Meriluoto, T.M. and Eranti, V. (2023) PLURALITY IN URBAN POLITICS: Conflict and Commonality in Mouffe and Thevenot. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 47(5), 693-709. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.13205

[57]. Haskins, E.V. (2015) Toward a Participatory Memory Culture. In Popular Memories: Commemoration, Participatory Culture, and Democratic Citizenship (pp. 117–130). University of South Carolina Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv6wghw7.11

[58]. Holtorf, C. and Bolin, A. (2024) Heritage Futures: A Conversation. Journal of Cultural Heritage. Management and Sustainable Development, 14(2), 252-265. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-09-2021-0156

[59]. Roth, R.E. (2021) Cartographic Design as Visual Storytelling: Synthesis and Review of Map-Based Narratives, Genres, and Tropes, The Cartographic Journal, 58(1), 83-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00087041.2019.1633103