1. Introduction

Polynesia is formed by thousands of islands scattered across the Pacific Ocean, including island groups such as Tonga, Samoa, Cooked Islands and French Polynesia, in which they share similar cultures and beliefs. Polynesian social structures are often centered around hierarchies led by clan chiefs or kings, who were seen as both the spiritual and political leaders. Religion played a central role, as chiefs were often considered to be divinely appointed or possessing a special connection to gods and ancestors. This belief granted them significant authority over land and resources, which were often controlled and distributed by the elites. This essay will focus on a comparative analysis of Samoa and Tonga—two significant islands within the Polynesian triangle. Both islands share religious practices and traditions where chiefs or kings hold authority, but they differ in the nature of their social hierarchies. Samoa tended to develop into a more egalitarian system, whereas Tonga developed a centralized monarchy. This comparison will highlight how different factors such as religious and economic factors influenced the development of social stratification in each society. In this essay we will first discuss the formation and differences in the political and economic structure between Tonga and Samoa that dated back to the prehistoric period. We will then look at factors such as religion, economic and geographical influences that formed the foundation of social stratification and discuss which factor had contributed the most.

2. Religion

2.1. Egalitarian Beginnings and Emergence of Hierarchies

In small, isolated island communities like Samoa and Tonga, religious beliefs were a key factor in the evolution of hierarchical systems from earlier egalitarian structures. Religion was not only a framework for spiritual practice but also helped to legitimize leadership and control resources. In Tonga, society became distinctly stratified into four classes: monarchy, nobles, commoners and ceremonial attendants. The monarchy, represented by the Tu’i Tonga, held supreme authority. This power was deeply rooted in mythology, with the first Tu’i Tonga, ‘Aho’eitu, described as the child of the god Tangaloa 'Eitumatupu'a, a divine ancestry that justified his rule and elevated his status above the nobles, commoners and ceremonial attendants [1].

2.2. Comparison

By contrast, Samoa, while maintaining a hierarchical structure, was relatively more egalitarian. Leadership within the Samoan matai system emphasized a balance of political and spiritual authority. Chiefs (matai) were chosen based on their perceived connections to gods and ancestors, as well as their ability to represent the collective interests of their clans (‘aiga) [2]. This system allowed for shared decision-making, with village councils (fono) operating as collaborative governance bodies. Unlike Tonga's centralized monarchy, Samoan religious leadership was dispersed, reflecting the decentralized nature of its societal structure [3].

3. The impact of Geographical Factors

Geography could also be argued as a central factor in shaping the societal structure of Tonga. The islands of Tonga are part of a volcanic arc, formed through intense geological activity associated with the Tonga-Kermadec Trench. This unique geological setting endowed the islands with highly fertile volcanic soils, rich in lime and iron oxides, particularly on islands like Tongatapu [4]. This soil supported robust agricultural productivity, allowing for surplus food production, which was critical in sustaining a growing population and fostering the rise of a centralized monarchy.

Tonga’s volcanic islands are aligned along en-echelon fractures and submarine ridges, which created clusters of habitable and resource-rich areas. This geographic clustering further concentrated resources, potentially enabling the formation of centralized governance. Fertile land and a strategic location within the volcanic arc were key factors that contributed to islands like Tongatapu emerging as centers of political and economic power. The nutrient-rich soils derived from basaltic and andesitic volcanic rocks provided the agricultural foundation that supported Tonga's hierarchical societal structure.

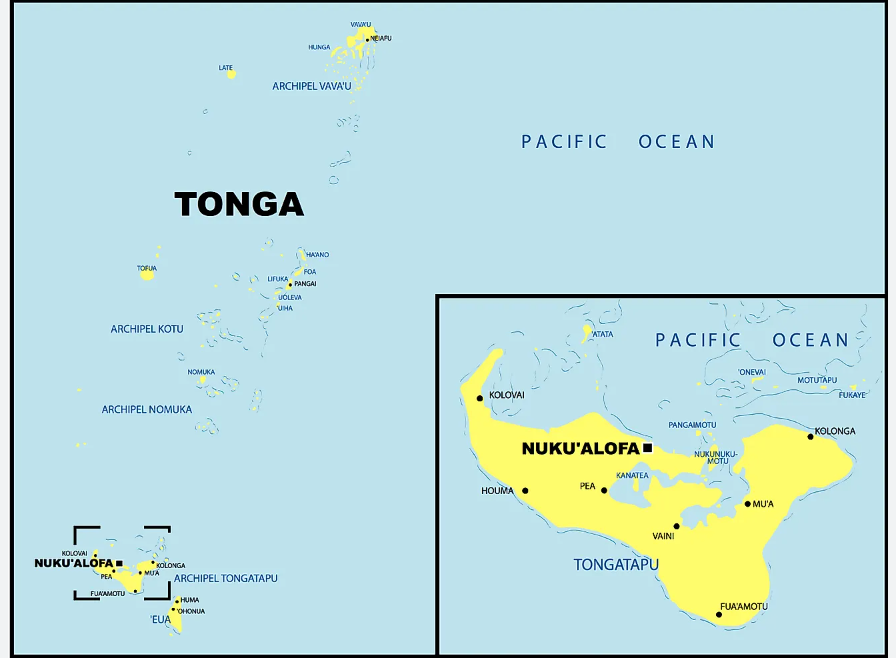

In contrast, while Tonga developed a highly stratified society under a centralized monarchy supported by fertile volcanic soils and concentrated resources, Samoa's rugged terrain and fragmented settlements gave rise to a localized form of governance. Figure 1 is a map of Samoa highlighting the mountainous terrain with darker areas indicating higher elevations [5]. The use of colors and shading indicates different types of land usage and elevation, portraying the fertile coastal plains used for agriculture and the less accessible, rugged interiors. This contrasts with Tonga, as shown in Figure 2, with its flatter landmass enabling the formation of centralized political and social structures [6]. Moreover, “From Corporate to Individual Land Tenure in Western Samoa” describes how villages were separated by geographic features such as coastal reefs and forested peaks, which delineated their lands and helped maintain their autonomy, indicating the communal land tenure system in Samoa played a crucial role in shaping Samoa’s decentralized structure [7]. This text further explains that extended family groups, known as 'aiga, collectively owned nearly all land and essential resources, such as agricultural plots, residential areas, and communal tools. Leadership and decision-making were managed by the family matai (chief), with land ownership remaining with the family unit across generations. This cooperative system ensured equitable resource management, reflecting the dispersed and locally focused nature of Samoan settlements (Figure 1).

Additionally, authority over land was not centralized but distributed among villages, with village councils, otherwise known as fono, tasked with protecting and managing land within their rule. These councils operated autonomously, overseeing areas that extended from coastal reefs to forested highlands. This arrangement, driven by the need to manage resources sustainably in a challenging environment, emphasized local decision-making and governance tailored to the unique needs of each community (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Map of Western Samoa [5]

Figure 2: Map of Tonga [6]

4. Resource control

In both Samoa and Tonga, religious beliefs were deeply integrated within the systems of resource control, contributing significantly to the consolidation of elite power. This relationship is clearly reflected in Tonga's centralized monarchy, where the divine authority of kings played a crucial role, and in Samoa's decentralized matai system, where land was managed at the clan level.

In Tonga, the monarchy derived its legitimacy from its divine connection to the god Tangaloa, and power was centralized through a patrilineal system of inheritance. This approach ensured that land remained under the control of nobles and chiefs, further embedding social hierarchies. Kaeppler notes that inheritance of wealth, particularly land, was strictly patrilineal, securing the transfer of resources from father to son [1].

Monumental tombs, such as those found at Lapaha, further emphasized this centralized authority. These tombs functioned as enduring markers of leadership, symbolizing and reinforcing the political power of the Tu’i Tonga lineage. According to Clark, the construction of these elite tombs was a means of documenting the power and legacy of Tongan chiefs over centuries [8].

Tonga’s centralized governance gave it an edge in regional politics. As Clark explains, the Tongan state, with its structured chiefly lines, was among the most powerful socio-political entities in prehistoric Oceania. Chiefs strengthened their authority by overseeing agriculture, land management, and ceremonial roles, which maintained social cohesion and stability [8-11].

4.1. Samoa: Decentralized Matai System

In contrast, Samoa’s matai system was characterized by communal land ownership, with land held collectively by extended families (‘aiga) and managed by chiefs. Unlike Tonga’s centralized authority, power in Samoa was more widely distributed. Chiefs were selected based on their contributions and the consensus of the family, rather than through strict inheritance, enabling a more flexible distribution of leadership roles [12,13].

However, this decentralization did not eliminate inequality. Tcherkézoff highlights that matai titles are tied to the founding ancestors of a family, and these ancestral names carry varying levels of status, with highborn individuals more likely to inherit titles with greater prestige and authority [2].

4.2. Institutionalization of Inequality

Both societies institutionalized inequality, though they approached it through different mechanisms. In Tonga, the combination of patrilineal inheritance and centralized governance entrenched a rigid social structure. Chiefs and nobles derived their power through their proximity to the monarchy, as Clark describes the high chiefs’ immense authority. Similarly, Kaeppler points out that societal ranking was ascribed at birth, creating a deeply stratified hierarchy [1].

In Samoa, while the matai system allowed for a more flexible transfer of power, certain families and clans accumulated resources and influence over time, perpetuating inequality. Tcherkézoff emphasizes that: “The position of matai makes itself felt not only in the family but in the village. The family is the center of social life; the village, that of political life amongst the Samoans.”

5. Conclusion

The comparative analysis of Samoa and Tonga reveals the significant role of religion and geography in shaping social stratification. In Tonga, the fertile and geographically compact environment fostered the emergence of a centralized monarchy, where divine authority upheld a rigid class hierarchy. In contrast, Samoa's dispersed geography and system of communal land ownership encouraged a decentralized governance structure that, while less hierarchical, still concentrated resources within elite families. Despite their differences, both societies institutionalized inequality through distinct mechanisms. This study highlights how the interplay of religious beliefs, economic structures, and geographical conditions forged unique pathways to social stratification, shedding light on the complexities of Polynesian societal organization.

References

[1]. Kaeppler, A.L. (1971) ‘Rank in Tonga’, Ethnology, 10(2), p. 174. doi:10.2307/3773008.

[2]. Tcherkézoff, S. (2000) Journal of the Polynesian Society: The Samoan category matai ('chief’): A singularity in Polynesia? historical and etymological comparative queries, by Serge Tcherkezoff, P 151-190, The Journal of the Polynesian Society. Available at: https://www.jps.auckland.ac.nz/document/?wid=5079&page=1&action=null (Accessed: 20 November 2024).

[3]. Mageo, J. (2002) ‘Myth, cultural identity, and Ethnopolitics: Samoa and the Tongan “empire”’, Journal of Anthropological Research, 58(4), pp. 493–520. doi:10.1086/jar.58.4.3630677.

[4]. Bryan, W.B., Stice, G.D. and Ewart, A. (1972) ‘Geology, petrography, and geochemistry of the volcanic islands of Tonga’, Journal of Geophysical Research, 77(8), pp. 1566–1585. doi:10.1029/jb077i008p01566.

[5]. Worldometers.info (ed.) (2024) Map of samoa (physical), Worldometer. Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/maps/samoa-map/ (Accessed: 06 December 2024).

[6]. WorldAtlas (2023) Tonga Maps & Facts, WorldAtlas. Available at: https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/tonga (Accessed: 20 November 2024).

[7]. O’Meara, J.T. (1995) ‘From corporate to individual land tenure in Western Samoa’, Land, Custom and Practice in the South Pacific, pp. 109–156. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511597176.005.

[8]. Clark, G. and Reepmeyer, C. (2014) ‘Stone architecture, monumentality and the rise of the early Tongan chiefdom’, Antiquity, 88(342), pp. 1244–1260. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00115431.

[9]. Burley, D.V. (1998) ‘Tongan Archaeology and the Tongan Past 2850–150 B.P. Journal of World Prehistory’, Journal of World Prehistory, 12(3), pp. 337–392. doi:10.1023/a:1022322303769.

[10]. Daly, M. (2009) Tonga: A new bibliography. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

[11]. Hommon, R.J. (2013) ‘The ancient Tongan State’, The Ancient Hawaiian State, pp. 187–200. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199916122.003.0013.

[12]. Kikuchi, W.K. (1964) Petroglyphs in American Samoa, Vol. 73, no. 2, June 1964 of the Journal of the Polynesian society on JSTOR. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/i20704169 (Accessed: 20 November 2024).

[13]. Martinsson-Wallin, H. (2016) Samoan archaeology and Cultural Heritage: Monuments and people, Memory and history. Oxford, Oxfordshire: Archaeopress.

Cite this article

Cao,L. (2025). Divine Authority and Social Hierarchies: A Comparative Study of Economic Inequality in Samoa and Tonga. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,81,57-62.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Kaeppler, A.L. (1971) ‘Rank in Tonga’, Ethnology, 10(2), p. 174. doi:10.2307/3773008.

[2]. Tcherkézoff, S. (2000) Journal of the Polynesian Society: The Samoan category matai ('chief’): A singularity in Polynesia? historical and etymological comparative queries, by Serge Tcherkezoff, P 151-190, The Journal of the Polynesian Society. Available at: https://www.jps.auckland.ac.nz/document/?wid=5079&page=1&action=null (Accessed: 20 November 2024).

[3]. Mageo, J. (2002) ‘Myth, cultural identity, and Ethnopolitics: Samoa and the Tongan “empire”’, Journal of Anthropological Research, 58(4), pp. 493–520. doi:10.1086/jar.58.4.3630677.

[4]. Bryan, W.B., Stice, G.D. and Ewart, A. (1972) ‘Geology, petrography, and geochemistry of the volcanic islands of Tonga’, Journal of Geophysical Research, 77(8), pp. 1566–1585. doi:10.1029/jb077i008p01566.

[5]. Worldometers.info (ed.) (2024) Map of samoa (physical), Worldometer. Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/maps/samoa-map/ (Accessed: 06 December 2024).

[6]. WorldAtlas (2023) Tonga Maps & Facts, WorldAtlas. Available at: https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/tonga (Accessed: 20 November 2024).

[7]. O’Meara, J.T. (1995) ‘From corporate to individual land tenure in Western Samoa’, Land, Custom and Practice in the South Pacific, pp. 109–156. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511597176.005.

[8]. Clark, G. and Reepmeyer, C. (2014) ‘Stone architecture, monumentality and the rise of the early Tongan chiefdom’, Antiquity, 88(342), pp. 1244–1260. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00115431.

[9]. Burley, D.V. (1998) ‘Tongan Archaeology and the Tongan Past 2850–150 B.P. Journal of World Prehistory’, Journal of World Prehistory, 12(3), pp. 337–392. doi:10.1023/a:1022322303769.

[10]. Daly, M. (2009) Tonga: A new bibliography. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

[11]. Hommon, R.J. (2013) ‘The ancient Tongan State’, The Ancient Hawaiian State, pp. 187–200. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199916122.003.0013.

[12]. Kikuchi, W.K. (1964) Petroglyphs in American Samoa, Vol. 73, no. 2, June 1964 of the Journal of the Polynesian society on JSTOR. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/i20704169 (Accessed: 20 November 2024).

[13]. Martinsson-Wallin, H. (2016) Samoan archaeology and Cultural Heritage: Monuments and people, Memory and history. Oxford, Oxfordshire: Archaeopress.