1. Introduction

Since Bai Juyi composed The Everlasting Regret, debates surrounding its theme have been ongoing. Broadly speaking, there are three main interpretations: the allegorical view, the romantic view, and the dual-theme view. The allegorical view holds that The Everlasting Regret satirizes and critiques the indulgence and excesses of the Tang rulers. The romantic view interprets the poem as a sympathetic celebration of the sincere and unwavering love between Emperor Xuanzong of Tang and Yang Guifei. The dual-theme view reconciles the previous two perspectives, suggesting that the poem contains both satirical critique and sympathetic celebration. While each perspective offers its own rationale, it also faces criticism. The allegorical interpretation focuses excessively on the poem's first half, which criticizes the indulgence and neglect of governance by Li and Yang, while overlooking the portrayal of their love in the second half. In contrast, the romantic interpretation emphasizes the second half's depiction of love, but neglects the satirical tone in the first half. The dual-theme interpretation, by attempting to combine both views, highlights the apparent inconsistency between the two halves, raising questions about whether The Everlasting Regret has a coherent theme throughout and whether it maintains artistic unity in structure [1].

Although extensive research on the theme of The Everlasting Regret has produced these representative interpretations, most of these studies are grounded in traditional literary criticism and seldom explore the poem from the perspective of modern linguistics or narratology. In particular, few studies have employed the emerging analytical framework of Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT) to conduct in-depth analysis. As a theory that combines linguistics with logic, SDRT effectively addresses complex narrative structures and the relationships between different semantic units within a text. For a work like The Everlasting Regret, which is replete with dramatic twists and emotional tension, analyzing its narrative coherence and the relationships between events is especially crucial. Therefore, applying the SDRT perspective to The Everlasting Regret holds significant theoretical value and fills a gap in existing research. This research aims to analyze the narrative structure and thematic expression of The Everlasting Regret through the framework of SDRT, exploring the poem's unique aspects in terms of narrative coherence, emotional progression, and event relations. In doing so, it offers new perspectives and methodologies for further understanding the thematic depth of this classic poem.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of SDRT

Discourse Representation Theory (DRT) was introduced by Hans Kamp and others in the 1980s as a dynamic semantic theory designed to address the limitations of Montague grammar in handling natural language phenomena [2]. Montague grammar gives us formal ways to look at semantics, but it is based on a truth-conditional semantics that is static, which doesn't work well when dealing with the fact that natural language semantics change over time and depend on the context. To overcome these shortcomings, Kamp developed DRT as a dynamic semantic framework capable of addressing issues such as anaphora resolution, temporal sequencing, and contextual dependencies across sentences, while revealing the connection between syntactic structures and semantic representations within a broader context. This, in turn, allows for a more effective treatment of discourse coherence.

However, as research progressed, DRT's limitations in handling complex discourse structures and rhetorical relations became apparent. Specifically, understanding discourse requires not only attention to local syntactic structures but also to global rhetorical structures and the pragmatic links between sentences. To extend DRT's explanatory power in cross-sentence coherence, Nicholas Asher and Alex Lascarides introduced Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT) [3]. By integrating rhetorical relations into the logical form of discourse, SDRT addresses issues of semantic reasoning within discourse coherence and effectively manages cross-sentence rhetorical and pragmatic relations, thus providing a more comprehensive and nuanced framework for semantic analysis.

SDRT introduces a distinction between coordination and subordination, which helps to analyze rhetorical relations such as Explanation, Contrast, and Result within the hierarchical structure of discourse [4]. Moreover, SDRT employs the concepts of Elementary Discourse Units (EDUs) and Compound Discourse Units (CDUs) to model discourse hierarchically. EDUs, as the smallest semantic units in discourse, are connected through rhetorical relations to form more complex CDUs. Rhetorical relations can further link these CDUs, creating even more intricate discourse structures. As a result, SDRT not only offers a systematic approach to local syntactic structures but also provides a detailed hierarchical model that explains global discourse coherence comprehensively. Given SDRT's advantages in analyzing complex discourse structures, this research seeks to apply it to the thematic study of The Everlasting Regret. By analyzing the text’s discourse structure and rhetorical relations, this research aims to uncover the underlying thematic logic of the poem and offer a detailed analysis of key units through rhetorical relations.

2.2. Overview of the Hierarchical Structure of The Everlasting Regret

As a narrative poem, The Everlasting Regret represents both a literary form and a type of discourse, characterized by overall coherence and unity. Its constituent parts are not randomly assembled but are connected through a few recurring rhetorical relations, which convey specific messages and emotions. Before analyzing how these parts form coherence, it is necessary to first explain the hierarchical structure of The Everlasting Regret. Scholars have differing opinions on how to segment the poem's structure, with interpretations ranging from two-part, three-part, four-part, to five-part divisions. Additionally, differences exist within each approach regarding the starting points of certain segments. This section will briefly introduce representative perspectives for each segmentation approach.

Table 1: Two-Part Division: Dividing the Poem into Two CDUs.

First perspective [5] | CDU 1 (lines 1-26) | Emperor Xuanzong’s indulgence. |

CDU 2 (lines 27-120) | Emperor Xuanzong’s profound longing for Yang Guifei. | |

Second perspective [6] | CDU 1 (lines 1-32) | The cause of the “regret”. |

CDU 2 (lines 33-120) | The “regret” itself |

Table 2: Three-Part Division: Dividing the Poem into Three CDUs.

First perspective [7] | CDU 1 (lines 1-42) | Emperor Xuanzong’s indulgence in pleasure, Yang Guifei’s arrogance, leading to the An Lushan Rebellion. |

CDU 2 (lines 43-74) | Emperor Xuanzong’s profound longing for Yang Guifei. | |

CDU 3 (lines 75-120) | The alchemist searches for Yang Guifei in heaven and earth and finally encounters her. | |

Second perspective [8] | CDU 1 (lines 1-30) | Emperor Xuanzong’s indulgence in pleasure, Yang Guifei’s arrogance. |

CDU 2 (lines 31-74) | The outbreak of the An Lushan Rebellion, Yang Guifei’s death, and Emperor Xuanzong’s grief. | |

CDU 3 (lines 75-120) | The alchemist searches for Yang Guifei and meets her. |

Table 3: Four-Part Division: Dividing the Poem into Four CDUs.

First perspective [9] | CDU 1 (lines 1-30) | Emperor Xuanzong’s indulgence in pleasure, Yang Guifei’s arrogance. |

CDU 2 (lines 31-50) | The An Lushan Rebellion, Yang Guifei’s death, and Emperor Xuanzong’s grief. | |

CDU 3 (lines 51-74) | Emperor Xuanzong’s deep longing for Yang Guifei after returning to Chang’an. | |

CDU 4 (lines 75-120) | The alchemist’s search for Yang Guifei and his encounter with her. | |

Second perspective [10] | CDU 1 (lines 1-26) | Yang Guifei’s entrance into the palace, her favor with the emperor, and the prosperity of her family. |

CDU 2 (lines 27-54) | The An Lushan Rebellion, Yang Guifei’s death, and Emperor Xuanzong’s lingering affection. | |

CDU 3 (lines 55-74) | Emperor Xuanzong’s deep longing for Yang Guifei after returning to Chang’an. | |

CDU 4 (lines 75-120) | The alchemist’s search for Yang Guifei and his encounter with her. | |

Third perspective [11, 12] | CDU 1 (lines 1-32) | Emperor Xuanzong’s indulgence in pleasure, Yang Guifei’s arrogance, leading to the An Lushan Rebellion. |

CDU 2 (lines 33-50) | Yang Guifei’s death and Emperor Xuanzong’s grief during exile. | |

CDU 3 (lines 51-74) | Emperor Xuanzong’s continuing longing for Yang Guifei after returning to Chang’an. | |

CDU 4 (lines 75-120) | The alchemist’s search for Yang Guifei and his encounter with her. | |

Fourth perspective [13] | CDU 1 (lines 1-26) | Yang Guifei’s beauty and the height of her favor in the palace. |

CDU 2 (lines 27-42) | The An Lushan Rebellion and Yang Guifei’s death. | |

CDU 3 (lines 43-74) | Emperor Xuanzong’s longing for Yang Guifei. | |

CDU 4 (lines 75-120) | The alchemist’s search for Yang Guifei and his encounter with her. | |

Fifth perspective [14] | CDU 1 (lines 1-30) | Emperor Xuanzong’s indulgence in pleasure, Yang Guifei’s arrogance. |

CDU 2 (lines 31-42) | The An Lushan Rebellion and Yang Guifei’s death. | |

CDU 3 (lines 43-74) | Emperor Xuanzong’s longing for Yang Guifei. | |

CDU 4 (lines 75-120) | The alchemist’s search for Yang Guifei and his encounter with her. |

Table 4: Five-Part Division: Dividing the Poem into Five CDUs.

First perspective [15] | CDU 1 (lines 1-26) | Yang Guifei’s entrance into the palace, her favor with the emperor, and the prosperity of her family. |

CDU 2 (lines 27-54) | The An Lushan Rebellion, Yang Guifei’s death, and Emperor Xuanzong’s lingering affection. | |

CDU 3 (lines 55-74) | Emperor Xuanzong’s deep longing for Yang Guifei after returning to Chang’an. | |

CDU 4 (lines 75-100) | The alchemist’s search for Yang Guifei and his encounter with her. | |

CDU 5 (lines 101-120) | Yang Guifei’s eternal vow to Emperor Xuanzong. | |

Second perspective [16] | CDU 1 (lines 1-26) | The emperor’s infatuation with Yang Guifei, her favor, and the arrogance of the Yang family. |

CDU 2 (lines 27-50) | The outbreak of the An Lushan Rebellion and the destruction of the love between the emperor and Yang Guifei. | |

CDU 3 (lines 51-74) | Emperor Xuanzong’s deep longing for Yang Guifei after returning to Chang’an. | |

CDU 4 (lines 75-100) | The alchemist’s search for Yang Guifei and his encounter with her. | |

CDU 5 (lines 101-120) | Yang Guifei’s eternal vow to Emperor Xuanzong. |

3. Methodology

This research adopts a qualitative approach, utilizing textual analysis within the theoretical framework of SDRT to conduct an in-depth discourse analysis of The Everlasting Regret. The focus is on deconstructing the rhetorical relations within the text to uncover its thematic expression.

Text Selection and Analysis: The study takes The Everlasting Regret as the primary object of analysis. Through careful reading and interpretation, the text is segmented into various discourse units (EDUs and CDUs).

Discourse Analysis: This research focuses on analyzing the rhetorical relations and coherence between different discourse units within the text. By examining how the text constructs its thematic structure through different narrative levels and semantic inferences, the study seeks to reveal how the poem articulates its thematic trajectory.

4. Results

Section 2.2 of this study introduced various perspectives on the hierarchical structure of The Everlasting Regret. This section will explain how different hierarchical divisions arise into distinct rhetorical relations.

The two-part division segments the poem into two CDUs. Although the two perspectives within the two-part division differ in their segmentation starting points, the rhetorical relationship between CDU1 and CDU2 is consistently identified as Result.

The three-part division splits the poem into three CDUs. Similar to the two-part division, the rhetorical relation between CDU1 and CDU2 is Result, while the relation between CDU2 and CDU3 is Violated Expectation.

The four-part division segments the poem into four CDUs, with five representative perspectives revealing two distinct types of rhetorical relations between the CDUs. In the first type (represented by the first, second, and third perspectives), the rhetorical relation between CDU1 and CDU2 is Result, between CDU2 and CDU3 is Narration, and between CDU3 and CDU4 is Violated Expectation. In the second type (represented by the fourth and fifth perspectives), the rhetorical relation between CDU1 and CDU2 is Result, between CDU2 and CDU3 is also Result, and between CDU3 and CDU4 is Violated Expectation.

The five-part division splits the poem into five CDUs, which similarly presents two types of rhetorical relations. In the first type, the rhetorical relation between CDU1 and CDU2 is Result, between CDU2 and CDU3 is Narration, between CDU3 and CDU4 is Violated Expectation, and between CDU4 and CDU5 is Narration. In the second type, the rhetorical relation between CDU1 and CDU2 is Result, between CDU2 and CDU3 is also Result, between CDU3 and CDU4 is Violated Expectation, and between CDU4 and CDU5 is Narration.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Impact of Different Hierarchical Divisions on the Theme

The two-part division splits the poem into two CDUs, with CDU1 serving as the basis for the allegorical interpretation and CDU2 forming the basis for the romantic interpretation. The transition from CDU1 to CDU2 represents a significant shift, and analyzing these two parts in isolation naturally leads to divergent views. However, from the perspective of rhetorical relations, there is a close link between CDU1 and CDU2. In CDU2, grief consumes Emperor Xuanzong after Yang Guifei's death, intensifying his longing for her to the point where he sends a Daoist priest to search for her soul. When viewed in isolation, CDU2 indeed portrays the sincere love between the emperor and Yang Guifei, transcending life and death. However, considering the rhetorical relationship between CDU1 and CDU2, it becomes apparent that Yang Guifei’s death was a result of Emperor Xuanzong’s indulgence and neglect of state affairs. It was precisely because of his infatuation with pleasure that the An Lushan Rebellion erupted, leading to Yang Guifei’s death, and consequently, Xuanzong’s profound sorrow for her. Therefore, the rhetorical relation between CDU1 and CDU2 is Result. Scholars who support the romantic interpretation argue that CDU2 is the main section of the poem, while CDU1 merely provides background, which implies that the rhetorical relation between CDU1 and CDU2 is Background. If rhetorical relations are divided into two types, subordination and coordination [4], Result is typically viewed as a coordination relation, while Background is seen as a subordination relation. Given the opposite nature of these two relations, it is impossible for CDU1 and CDU2 to simultaneously possess both Result and Background relations, suggesting that one of these analyses may be flawed. In SDRT, coordination shifts the scene and advances the narrative, while subordination elaborates on the scene, deepening the narrative [4]. From CDU1 to CDU2, the scene has indeed changed: CDU1 describes the prosperous times before the rebellion, with the emperor and consort immersed in pleasure, while CDU2 depicts the aftermath of the rebellion, with the Tang dynasty’s glory gone and the life of luxury vanished. This change in scene follows a linear temporal sequence, which aligns with the characteristics of a coordination relation. Viewing the rhetorical relation between CDU1 and CDU2 as Result shifts the theme of The Everlasting Regret towards an allegorical interpretation: the deeper Emperor Xuanzong’s feelings for Yang Guifei, the greater his regret for his past neglect of state affairs, thereby strengthening the poem’s cautionary message. However, given that CDU2 depicts Xuanzong’s deep longing and the sincere love between the emperor and Guifei, the poem’s satire is not harsh but rather a subtle form of critique, expressed through the lens of "emotion."

The three-part division splits the poem into three CDUs. As previously analyzed, the rhetorical relation between CDU1 and CDU2 is Result, and this will not be reiterated here. The focus now shifts to the relation between CDU2 and CDU3. After Yang Guifei’s death, Emperor Xuanzong is overcome with sadness in Sichuan, reflects on his memories of her on the return journey, and continues to grieve after returning to the palace. His longing for her reaches such an intensity that even the mere sight of her in a dream would provide some solace, yet this expectation remains unmet, leading to his decision to have a Daoist priest search for Yang Guifei’s soul. It is important to note that Emperor Xuanzong only decides to seek Yang Guifei’s soul because her spirit had not appeared to him in a dream. However, the outcome, as presented in CDU3, is that the priest only brings back tokens and vows from Yang Guifei, rather than a reunion. Xuanzong’s anticipated result is thus denied, and the rhetorical relation between CDU2 and CDU3 is Violated Expectation. Unlike CDU1 and CDU2, CDU3 represents an imaginary celestial realm created by the poet, rather than a real-world setting. Given this fictional setting, why does the poet not allow Xuanzong and Yang Guifei to reunite, constructing a Result relation, but instead chooses a Violated Expectation relation? If the purpose were merely to highlight the tragic nature of their love, why further construct this tragedy? The poet’s choice to prolong rather than resolve Xuanzong’s suffering is itself a subtle critique of the emperor. Emperor Xuanzong’s indulgence in pleasure led to the An Lushan Rebellion, causing national turmoil and immense suffering for the people. The consequences were so severe that even in the imaginary celestial realm, the two cannot and should not reunite. Only through unresolved suffering can the consequences of neglecting state affairs be fully realized, emphasizing that a ruler’s priority should be the welfare of the state and its people. The construction of Violated Expectation ensures that the discourse consistently adheres to a singular theme, maintaining coherence between the poem’s parts, rather than splitting into two separate themes of satire and love.

The four-part division splits the poem into four CDUs, with five representative perspectives, leading to two types of rhetorical relations between the CDUs. The difference lies only in the rhetorical relation between CDU2 and CDU3, where one type identifies it as Narration and the other as Result. However, since Result is sometimes considered a causal intensification of Narration [17], these two types are essentially the same. Whether the causal relation between Emperor Xuanzong’s indulgence and the outbreak of the An Lushan Rebellion is made explicit, or Xuanzong’s longing for Yang Guifei is divided into spatial and temporal sequences to show continuity, neither interpretation alters the conclusions drawn earlier. Making the causal relation explicit undoubtedly reinforces the poem’s satirical critique of Emperor Xuanzong. Meanwhile, the more detailed segmentation of Xuanzong’s longing for Yang Guifei might seem to emphasize their love, but as previously discussed, the deeper the love, the greater the pain, and the deeper the regret, resulting in a stronger cautionary message. The fact that different segmentation methods do not affect the thematic interpretation underscores that The Everlasting Regret has a clear theme. The coherence of the poem ensures that the theme naturally emerges through continuous narration, regardless of how the hierarchy is segmented.

Compared to the four-part division, the five-part division further subdivides the poem’s imaginary realm. Using “Like a spray of pear blossoms in spring rain impearled” as a dividing point, lines 75 to 120 are split into two parts, connected by Narration, highlighting spatial and temporal continuity without altering the previous conclusion: The Everlasting Regret does not have dual themes, but rather a single theme. This theme is not a celebration of love but a subtle and nuanced form of satire.

5.2. The Internal Connection Between the Three Rhetorical Relations

In the analysis of the two-part division in Section 5.1, this research pointed out that the rhetorical relation between CDU1 and CDU2 cannot simultaneously be both Result and Background. SDRT does not deny the possibility of multiple rhetorical relations between discourse units, but the premise is that these multiple relations must not contradict or conflict with each other. In other words, coordination and subordination relations cannot coexist between two discourse units. In The Everlasting Regret, the possibility of multiple rhetorical relations is illustrated in lines 27-34. These eight lines can be analyzed into 16 Elementary Discourse Units (EDUs) as follows:

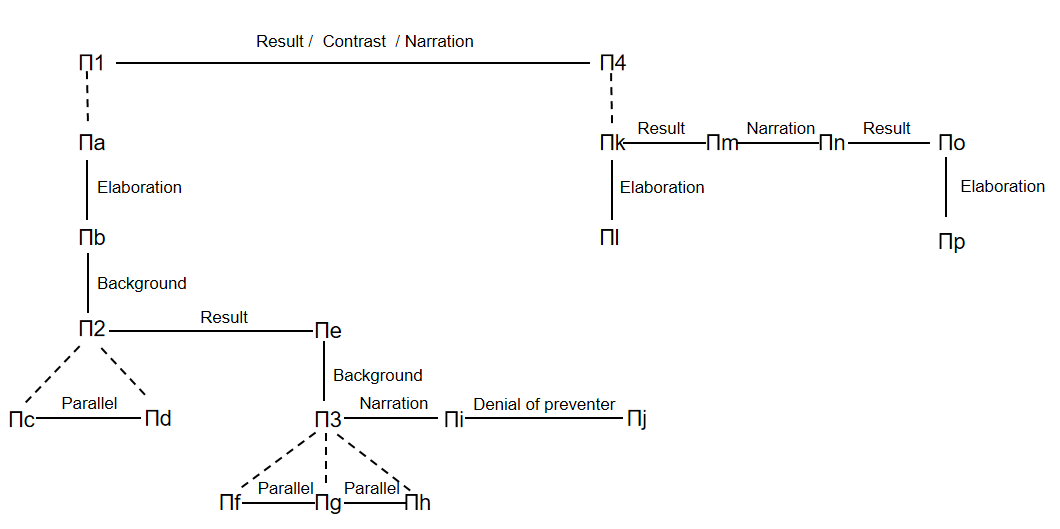

Πa: The Huaqing Palace stands tall.

Πb: The palace reaches high into the clouds.

Πc: The music is beautiful.

Πd: The music floats on the wind.

Πe: The music can be heard everywhere.

Πf: The emperor enjoys the wind instruments.

Πg: The emperor enjoys the string instruments.

Πh: The emperor enjoys the dance.

Πi: The emperor is still not satisfied.

Πj: The emperor watches the performances all day and night.

Πk: The war drums of Yuyang sound.

Πl: The drums shake the earth.

Πm: The drums break the performance of the "Song of Rainbow Skirt and Coat of Feathers."

Πn: War erupts in the capital.

Πo: Thousands of chariots and horses escort the emperor away from Chang’an.

Πp: They flee to the southwest.

Figure 1: Graph of Semantic Representations of Discourse Units.

Π1 is the CDU composed of Πa-Πj, and Π4 is the CDU composed of Πk-Πp. The rhetorical relation between Π1 and Π4 can be interpreted in three ways: Contrast, Result, and Narration. Since all three of these rhetorical relations belong to coordination relations, they do not conflict with each other, making it entirely possible for all three to coexist between Π1 and Π4.

First, Narration: The progression from performing dances and music to stopping the performance, and from a state of peace to a state of war, demonstrates temporal and spatial continuity. Second, Result: as previously mentioned, the outbreak of the An Lushan Rebellion was not accidental but was caused by Emperor Xuanzong’s indulgence and neglect of state affairs. Therefore, the rhetorical relation between Π1 and Π4 is not only Narration but an enhancement of Narration through a causal relationship, i.e., Result. Lastly, Contrast: the same imagery appears in both Π1 and Π4, specifically, the "Song of Rainbow Skirt and Coat of Feathers". This piece of music has a rich rhythm, starting slow and becoming intense. The phrase "slow dance and fluted or stringed song" represents the beginning phase of the piece, where the rhythm is slow. The term "break" in the phrase "And 'Song of Rainbow Skirt and Coat of Feathers' break" carries two distinct meanings, thereby establishing three levels of contrast. The first meaning of “break” is “to interrupt,” as the war drums stopped the performance, forming the first contrast: the performance was ongoing versus the performance was stopped. At the same time, “break” is also a technical term in ancient Chinese music [18], indicating the climax of the piece, where the rhythm becomes fast and intense. This creates the second contrast between the slow rhythm in the earlier part and the rapid rhythm in the later part. The change in rhythm in the "Song of Rainbow Skirt and Coat of Feathers" also metaphorically reflects societal change, with the slow rhythm symbolizing the peaceful times before the rebellion and the fast rhythm symbolizing the outbreak of the rebellion, which ended the peace. Therefore, the third contrast between Π1 and Π4 represents the difference between a "peaceful society" and "societal turmoil."

The existence of these three non-conflicting rhetorical relations between Π1 and Π4 implies a logical connection between them. (1) Result is a type of causal relation, where the cause precedes the effect. In terms of temporal sequence, the cause must occur before the effect; without the former, the latter cannot exist. Result expresses the causal relationship based on the temporal order, further explaining the causal link through the timeline. Therefore, Result encompasses Narration, and if the rhetorical relation between Π1 and Π4 can be interpreted as Result, then it can also reasonably be interpreted as Narration. (2) Different causes lead to different effects, and contrasting these different effects can reflect a Contrast relation. The peaceful times depicted in Π1 are the result of Emperor Xuanzong’s early diligent governance, while the turmoil shown in Π4 is the result of his later indulgence and neglect of state affairs. These two outcomes form a clear contrast, allowing the rhetorical relation between Π1 and Π4 to be interpreted as Contrast. (3) There is also a connection between Contrast and Narration. Narration describes the temporal and spatial continuity of events, and events occurring in different times and spaces may differ, thus leading to Contrast.

6. Conclusion

Different hierarchical divisions affect the interpretation of rhetorical relations, which in turn influence the interpretation of the text's theme. However, the analysis of The Everlasting Regret shows that despite these different divisions, they do not lead to multiple thematic interpretations. Instead, they converge on a single thematic direction, indicating that the poem has a singular theme rather than a dual one. The theme is not a celebration of love, but rather a subtle form of satire. The reason for this is likely that the various hierarchical divisions have not fundamentally altered the nature of the rhetorical relations between the internal components of the text. The relationship between the hierarchical structure, rhetorical relations, and the text’s theme is highly complex, and The Everlasting Regret only illustrates one possible scenario. A more comprehensive understanding of this interactive mechanism requires the analysis of more complex texts.

The possibility of multiple non-conflicting rhetorical relations between discourse units suggests, to some extent, that there may be certain connections between these rhetorical relations. Through the analysis of The Everlasting Regret, this paper has explored the connections between the rhetorical relations of Narration, Result, and Contrast. Further research and discussion are still needed to determine whether similar connections exist between other rhetorical relations, and which factors determine the presence or absence of logical connections between them.

References

[1]. Zhang Zhongyu. 2005. A Structural Study of Bai Juyi's "The Everlasting Regret". Journal of Hainan Normal University (Social Sciences Edition), Issue 5.

[2]. Kamp, Hans, and Uwe Reyle. 1993. From Discourse to Logic: Introduction to Model Theoretic Semantics of Natural Language, From Logic and Discourse Representation Theory. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 486–489.

[3]. Asher, N., and A. Lascarides. 2003. Logics of Conversation: Studies in Natural Language Processing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[4]. Nicholas Asher and Laure Vieu. 2005. Subordinating and coordinating discourse relations. Lingua, 115(4):591–610.

[5]. You Guoen. 1963. A History of Chinese Literature (Volume 2). Beijing: People's Literature Publishing House.

[6]. Huo Songlin. 1995. Selected Tang Poems. Nanjing: Jiangsu Ancient Books Publishing House.

[7]. Yuan Xingpei. 1999. A History of Chinese Literature (Volume 2). Beijing: Higher Education Press.

[8]. Jin Jicang. 2002. Detailed Explanation of "The Everlasting Regret" and Other Poems on the Same Theme. Taiyuan: Shanxi Ancient Books Publishing House.

[9]. Gong Kechang and Peng Chongguang. 1984. Selected Annotations of Bai Juyi's Poetry and Prose. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House.

[10]. Xia Chuancai. 1995. Selected Readings of Chinese Classical Literature: Volume 2. Beijing: Language and Literature Publishing House.

[11]. Zhang Buyun. 1990. Tang Dynasty Poetry. Hefei: Anhui Education Publishing House.

[12]. Cheng Qianfan. 2000. Famous Poems of Tang and Song Dynasties. Shenyang: Liaoning People's Publishing House.

[13]. Lin Geng and Feng Yuanjun. 1979. Anthology of Chinese Poetry through the Ages: Volume 1. Beijing: People's Literature Publishing House.

[14]. Liao Zhong'an and Liu Guoying. 1989. Dictionary of Classical Chinese Literature. Beijing: Beijing Publishing House.

[15]. Su Zhongxiang. 1957. Selected Poems of Yuan Zhen and Bai Juyi. Shanghai: Classical Literature Publishing House.

[16]. Ding, Ruming, et al. 1993. Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poetry. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House.

[17]. Hobbs, J. R. 1985. On the Coherence and Structure of Discourse. Technical Report CSLI-85-37. CSLI, Stanford University.

[18]. Yao Ronghua. 2014. The Imagery of "Nishang Yuyi" in the "The Everlasting Regret". Literary Contention, Issue 8.

Cite this article

Hu,M. (2025). Analyzing the Theme of The Everlasting Regret from the Perspective of Segmented Discourse Representation Theory. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,82,36-45.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Zhang Zhongyu. 2005. A Structural Study of Bai Juyi's "The Everlasting Regret". Journal of Hainan Normal University (Social Sciences Edition), Issue 5.

[2]. Kamp, Hans, and Uwe Reyle. 1993. From Discourse to Logic: Introduction to Model Theoretic Semantics of Natural Language, From Logic and Discourse Representation Theory. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 486–489.

[3]. Asher, N., and A. Lascarides. 2003. Logics of Conversation: Studies in Natural Language Processing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[4]. Nicholas Asher and Laure Vieu. 2005. Subordinating and coordinating discourse relations. Lingua, 115(4):591–610.

[5]. You Guoen. 1963. A History of Chinese Literature (Volume 2). Beijing: People's Literature Publishing House.

[6]. Huo Songlin. 1995. Selected Tang Poems. Nanjing: Jiangsu Ancient Books Publishing House.

[7]. Yuan Xingpei. 1999. A History of Chinese Literature (Volume 2). Beijing: Higher Education Press.

[8]. Jin Jicang. 2002. Detailed Explanation of "The Everlasting Regret" and Other Poems on the Same Theme. Taiyuan: Shanxi Ancient Books Publishing House.

[9]. Gong Kechang and Peng Chongguang. 1984. Selected Annotations of Bai Juyi's Poetry and Prose. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House.

[10]. Xia Chuancai. 1995. Selected Readings of Chinese Classical Literature: Volume 2. Beijing: Language and Literature Publishing House.

[11]. Zhang Buyun. 1990. Tang Dynasty Poetry. Hefei: Anhui Education Publishing House.

[12]. Cheng Qianfan. 2000. Famous Poems of Tang and Song Dynasties. Shenyang: Liaoning People's Publishing House.

[13]. Lin Geng and Feng Yuanjun. 1979. Anthology of Chinese Poetry through the Ages: Volume 1. Beijing: People's Literature Publishing House.

[14]. Liao Zhong'an and Liu Guoying. 1989. Dictionary of Classical Chinese Literature. Beijing: Beijing Publishing House.

[15]. Su Zhongxiang. 1957. Selected Poems of Yuan Zhen and Bai Juyi. Shanghai: Classical Literature Publishing House.

[16]. Ding, Ruming, et al. 1993. Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poetry. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House.

[17]. Hobbs, J. R. 1985. On the Coherence and Structure of Discourse. Technical Report CSLI-85-37. CSLI, Stanford University.

[18]. Yao Ronghua. 2014. The Imagery of "Nishang Yuyi" in the "The Everlasting Regret". Literary Contention, Issue 8.