1. Introduction

Social interaction is a fundamental aspect of human well-being, influencing both psychological and physiological health. Humans are inherently social beings, and social bonds play a crucial role in maintaining emotional stability, reducing stress, and fostering a sense of belonging. Studies have shown that strong social connections correlate with increased life satisfaction and lower risks of mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression [1]. Additionally, individuals with rich social networks exhibit better physical health outcomes, including lower inflammation levels and reduced risks of cardiovascular disease [2]. Conversely, social isolation has been linked to negative mental and physical health consequences, demonstrating the necessity of human connection for overall well-being.

The mode of social interaction—whether in-person or online—has been found to have distinct effects on well-being. Face-to-face interactions tend to foster deeper emotional connections, enhance social support, and contribute to stronger feelings of belonging [3]. In contrast, while online interactions provide access to a broad network of social ties, they do not always translate to meaningful connections. Some research suggests that excessive social media use is associated with loneliness and decreased well-being [4], while others argue that online platforms can enhance social support and reduce isolation, particularly among individuals with limited mobility or social anxiety [5]. These divergent findings suggest that the quality, rather than the quantity, of social interactions—both online and offline—may be a key factor in determining their impact on happiness.

Despite extensive research on social interaction and well-being, there remain controversies in the field that warrant further study. One debate concerns whether social media acts as a supplement or a substitute for in-person interactions, with some scholars asserting that digital communication erodes meaningful relationships while others contend that it strengthens them [6,7]. Additionally, the effects of solitude and its role in happiness remain understudied. Some research suggests that moderate levels of solitude can be beneficial, providing individuals with opportunities for self-reflection and personal growth [8], while other studies highlight the risks of prolonged social withdrawal, particularly among young adults who adopt NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) lifestyles. In the past, torture methods such as white room have even included a lack of social interaction to mentally wear down victims, indicating the importance of contact with others [9]. Similarly, due to the importance of social contact for human beings, the correlation of a multitude of mental illnesses with social interaction again highlights the importance of this contact [10]. Given the increasing prevalence of digital interactions and shifting social norms, a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between social interaction and happiness is necessary.

The goal of this study is to empirically investigate the relationship between social interaction—both in-person and online—and subjective well-being using a survey-based research method. By collecting data on participants’ frequency and quality of social interactions, as well as their self-reported happiness levels, this study aims to provide a nuanced understanding of how different modes of social engagement impact well-being. The survey consists of three key sections: in-person social interaction, online social interaction, and a validated happiness measure using the Oxford Happiness Questionnaire. By analyzing these responses, the study seeks to determine whether one form of social interaction is more strongly correlated with well-being than the other and whether an optimal balance exists between the two. Additionally, this research will explore potential moderating factors, such as age, environment, and personality traits, that may influence the relationship between social interaction and happiness. By leveraging empirical data, this study aims to contribute to the ongoing discourse on social connectivity and mental health, addressing gaps in existing literature and informing future interventions designed to enhance well-being.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 42 participants were recruited through convenience sampling, including responses from family, friends, and individuals on the internet. Participants were not restricted by demographic factors such as age, gender, or geographic location, allowing for a diverse dataset. Given the voluntary nature of participation, self-selection bias may be a potential limitation of the study.

2.2. Materials

The study utilized an online survey, available in English, to accommodate a broader participant pool. The survey was hosted on SurveyMonkey and could be accessed via the following link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/5CFM6TQ. The survey was designed to measure participants’ levels of in-person and online social interaction, as well as their subjective well-being.

The survey consisted of three key sections:

1. Social Interaction (In-Person and Online): Participants rated their frequency and quality of in-person and online social interactions on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very frequent/meaningful).

2. Well-Being Measurement: The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire was used to assess subjective well-being. Participants responded to statements about happiness on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), with total scores indicating overall happiness levels.

3. Demographic and Background Information: Additional questions on age, gender, and environment were included to account for potential confounding variables and enable subgroup analysis.

2.3. Procedure

Participants accessed the survey online and provided informed consent before proceeding. They completed the questionnaire independently, with no time constraints imposed. Once responses were collected, data were analyzed to identify correlations between social interaction (both in-person and online) and self-reported well-being. The study aimed to determine whether the frequency and mode of social interaction significantly influenced participants’ happiness scores and to explore potential moderating variables that could impact this relationship.

2.4. Data analysis

Quantitative data from the survey were analyzed using statistical methods to assess correlations between in-person social interaction, online social interaction, and happiness scores. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics, and inferential analyses (such as correlation coefficients) were conducted to evaluate the strength and direction of relationships between variables.

3. Results

To assess the distribution of the three key variables—social interaction online, social interaction in person, and happiness scores—we conducted a normality test using the kurtosis normality test. The results indicated that while social interaction online and social interaction in person followed approximately normal distributions (ps>0.05), happiness scores deviated from normality based on the kurtosis measure (p<0.05). Given this non-normality, Pearson correlation analysis was chosen as the appropriate statistical method to examine the relationships between social interaction (both online and in-person) and happiness, as Pearson correlation remains robust for non-normally distributed data.

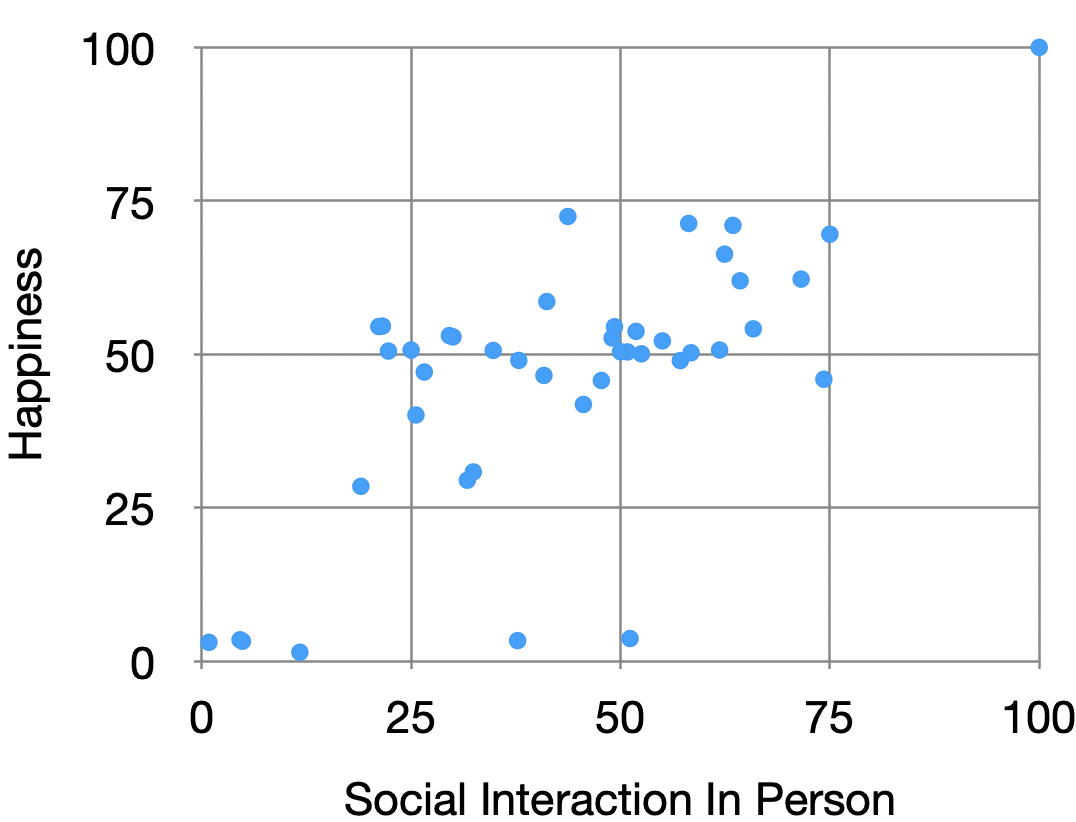

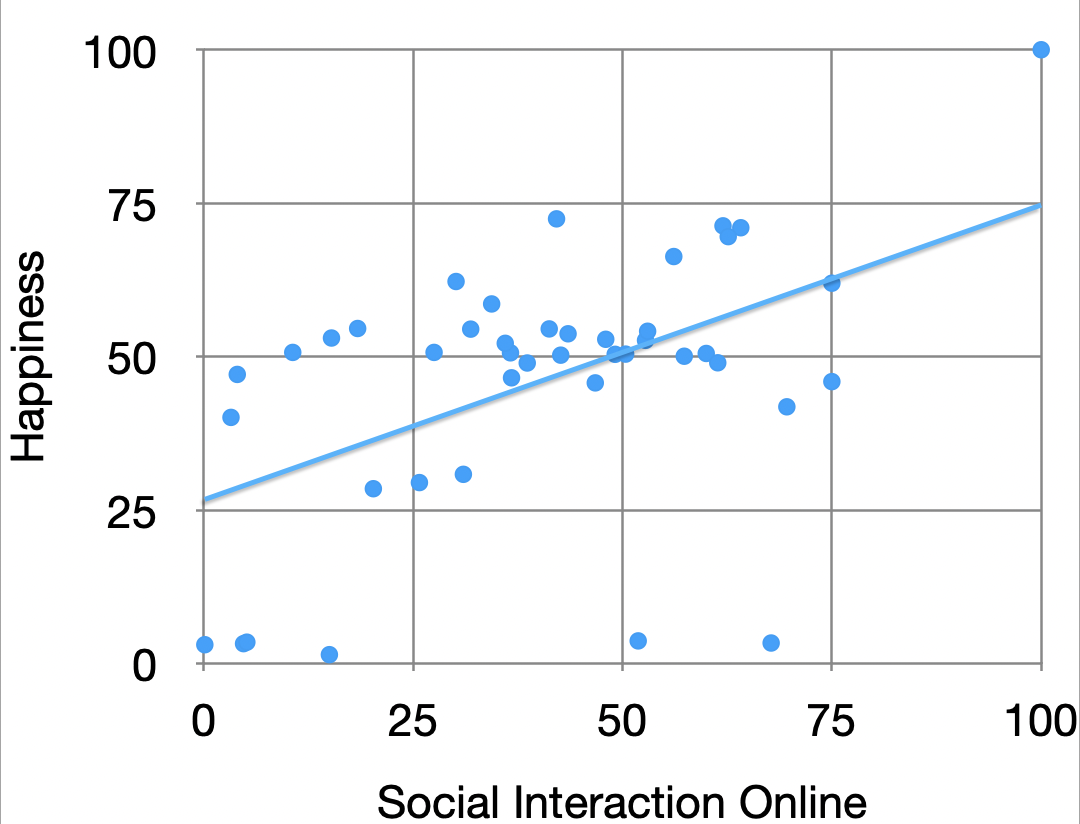

The Pearson correlation analysis revealed a moderate to high positive correlation between both types of social interaction and happiness scores. Specifically, in-person social interaction showed a stronger correlation with happiness compared to online social interaction, suggesting that face-to-face interactions may have a more pronounced impact on well-being (r=0.69, p<0.01), as shown in Graph 1.. However, online social interaction also exhibited a significant positive correlation (r=0.75, p<0.01), indicating that virtual connections can contribute to happiness, though possibly to a lesser extent than in-person interactions. This result is shown in Graph 2. These findings support the hypothesis that individuals who engage in more frequent social interactions, regardless of mode, tend to report higher levels of happiness.

Figure 1: Correlation between social interaction in person and happiness.

Figure 2: Correlation between social interaction online and happiness.

4. Discussion

The results of this study reaffirm the critical role of social interaction in human well-being, demonstrating that both in-person and online interactions are positively correlated with happiness. This finding supports previous research showing that individuals with richer social networks tend to experience greater life satisfaction and lower levels of stress and mental health issues [1,2]. However, our findings also indicate that in-person social interactions have a stronger correlation with happiness than online interactions, which aligns with research suggesting that face-to-face interactions foster deeper emotional connections and social bonding [11]. The importance of physical presence in social relationships may stem from the ability to interpret nonverbal cues, share synchronized emotional experiences, and establish a greater sense of intimacy—factors that digital communication often lacks [12].

Despite the positive correlation between online social interaction and happiness, its weaker effect compared to in-person interactions raises questions about the quality of digital communication. While some studies suggest that online interactions can provide emotional support and mitigate loneliness, particularly for individuals with social anxiety or mobility constraints [5], others caution that excessive reliance on digital communication can lead to superficial social connections and increased loneliness [13]. The current study suggests that while online interaction contributes to well-being, it may not fully replace the benefits of in-person socialization. One possible explanation is that online interactions often involve passive engagement, such as scrolling through social media feeds, rather than active, meaningful exchanges. This aligns with findings that passive social media use is associated with lower well-being, whereas active engagement, such as direct messaging or video calls, can have more positive effects [14].

Given the increasing integration of digital communication into daily life, future research should explore how different modes of online interaction impact well-being. Longitudinal studies could investigate whether shifts from in-person to online interactions have long-term effects on happiness and whether certain groups, such as younger generations or individuals living in isolation, experience different outcomes. Furthermore, experimental studies could examine whether interventions aimed at increasing meaningful online engagement—such as structured virtual communities or video-based interactions—can enhance well-being. The present study contributes to the growing discourse on social connectivity and mental health by highlighting the continued importance of face-to-face interactions while recognizing the evolving role of digital communication in shaping human relationships. As social norms continue to change, a better understanding of how to balance in-person and online interactions will be crucial for promoting long-term well-being.

5. Conclusion

Through the findings from this survey, it can be concluded that social interaction (online and/or offline) is correlated with positive psychological health. Pearson correlation analysis results demonstrated that although both types of social interaction show a strong positive correlation with happiness, in-person and direct interaction show a stronger correlation. This demonstrated that though the advancement of society highlights the benefits of digital communication, it still cannot fully replace in person interaction. The results for this study support current research focusing on the importance of social interaction for human beings with further research needed to continue exploring the possibilities of continued technological breakthroughs in the modern world.

References

[1]. Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84.

[2]. Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLOS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316.

[3]. Sandstrom, G. M., & Dunn, E. W. (2014). Social interactions and well-being: The surprising power of weak ties. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(7), 910–922.

[4]. Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased social media use. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–17.

[5]. Nowland, R., Necka, E. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2018). Loneliness and social Internet use: Pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), 70–87.

[6]. Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Vicario, M. D., Puliga, M., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). Users polarization on Facebook and YouTube. PLOS ONE, 11(8), e0159641.

[7]. Orben, A., Dienlin, T., Przybylski, A. K., & Blakemore, S. J. (2019). Social media’s enduring effect on adolescent life satisfaction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(21), 10226–10228.

[8]. Nguyen, T. T., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2018). Solitude as an approach to affective self-regulation and happiness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(1), 92–106.

[9]. Maiti, N. D., & Sarvand, N. V. (2022). “White Room Torture” A Sensory Denial Method which Obliterates All Sense of Realism. International Journal of Psychiatric Nursing, 9(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijpn.v9i1.18824

[10]. Young S. N. (2008). The neurobiology of human social behaviour: an important but neglected topic. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience : JPN, 33(5), 391–392.

[11]. Reis, H. T., Sheldon, K. M., Gable, S. L., Roscoe, J., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(4), 419–435.

[12]. Gonzales, A. L. (2014). Text-based communication influences self-esteem more than face-to-face or cellphone communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 197–203.

[13]. Kross, E., Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., Park, J., Seungjae, L., Lin, N., … & Ybarra, O. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLOS ONE, 8(8), e69841.

[14]. Verduyn, P., Ybarra, O., Résibois, M., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2017). Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11(1), 274–302.

Cite this article

Ren,C.S. (2025). The Impact of In-Person and Online Social Interaction on Happiness: An Empirical Study on Social Connectivity and Well-Being. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,89,112-117.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Education Innovation and Psychological Insights

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84.

[2]. Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLOS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316.

[3]. Sandstrom, G. M., & Dunn, E. W. (2014). Social interactions and well-being: The surprising power of weak ties. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(7), 910–922.

[4]. Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased social media use. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–17.

[5]. Nowland, R., Necka, E. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2018). Loneliness and social Internet use: Pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), 70–87.

[6]. Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Vicario, M. D., Puliga, M., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). Users polarization on Facebook and YouTube. PLOS ONE, 11(8), e0159641.

[7]. Orben, A., Dienlin, T., Przybylski, A. K., & Blakemore, S. J. (2019). Social media’s enduring effect on adolescent life satisfaction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(21), 10226–10228.

[8]. Nguyen, T. T., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2018). Solitude as an approach to affective self-regulation and happiness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(1), 92–106.

[9]. Maiti, N. D., & Sarvand, N. V. (2022). “White Room Torture” A Sensory Denial Method which Obliterates All Sense of Realism. International Journal of Psychiatric Nursing, 9(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijpn.v9i1.18824

[10]. Young S. N. (2008). The neurobiology of human social behaviour: an important but neglected topic. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience : JPN, 33(5), 391–392.

[11]. Reis, H. T., Sheldon, K. M., Gable, S. L., Roscoe, J., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(4), 419–435.

[12]. Gonzales, A. L. (2014). Text-based communication influences self-esteem more than face-to-face or cellphone communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 197–203.

[13]. Kross, E., Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., Park, J., Seungjae, L., Lin, N., … & Ybarra, O. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLOS ONE, 8(8), e69841.

[14]. Verduyn, P., Ybarra, O., Résibois, M., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2017). Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11(1), 274–302.