1. Introduction

Protectionist refers to government policies protecting domestic production from foreign competition. For instance, if US set tariff of 15% on an automobile that costs $9,000 in a foreign country, the tax at customs duty of $1,350 will be levied on the car as it imported into US. Therefore, the foreign company will have to sell their product at $10,350 in the US market, while the similar car manufactured domestically in US are able to receive a high profit, since there are no tax expenses from customs duty. Government policies, such as tariffs, import quotas, and subsidies, have historically been employed to shield home industries from international competition. Although they may offer short-term development in those industries, sustained protectionism frequently results in retaliatory trade actions, diminished market efficiency, and economic volatility. The revival of protectionism, especially in the context of US-China trade conflicts, has produced worldwide consequences, impacting economies of all sizes [1]. China, a significant global manufacturing center, faces trade limitations that affect its export-oriented economy; while Canada, a resource-dependent economy, must manage the intricacies of trade reliance, especially with the United States [2]. Comprehending the differing effects of protectionist policies on these two economies underscores the wider ramifications of trade restrictions in the contemporary global economy.

Economist contends that temporary trade barriers might assist domestic industries in adapting to global competitiveness, nevertheless, protectionism leads to inefficiencies. While developing economies, such as China, may implement trade restrictions to foster domestic industry development, over dependence on protectionist measures can impede sustained economic advancement. Additionally, Canada’s vulnerability to alterations in trade policy owes to its reliance on the US market.

This article examines the economic implications of protectionist trade policies on China and Canada. It analyzes their unique economic vulnerabilities, responses, and measures for alleviating the detrimental impacts of protectionism. This study seeks to deliver a thorough evaluation of how each nation responds to economic data and policy developments. This paper first analyses the impacts of protectionism alongside theoretical frameworks on trade barriers and economic policy. The efficacy of historical and contemporary trade policy is evaluated to provide strategic solutions to economic disturbances. This article examines the effects of protectionist trade policies on China and Canada through the integration of several techniques. Moreover, the study analyzes the impact of how Canadian government insulates the effect.

2. Protectionism

Protectionism implies government actions intended to safeguard domestic businesses from international competition, mainly implemented via tariffs, subsidies, or quotas. Although these policies may appear advantageous in the short term, significant economic literature indicates they typically lead to inefficiencies and distractions in global trade. This inefficiency results in misallocated resources and increased consumer expenses; while certain individuals may benefit from protections, the aggregate loss in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is enormous. Research states that an additional viewpoint by recognizing the strategies of temporarily protecting some essential industries through policy could augment national welfare, especially when these businesses are variable at the beginning age of building up their competitive capabilities [3]. Therefore, as long as the short-term protection can assist business to integrate into the competitive markets, then it is beneficial. Additionally, the protectionist might be needed by the developing countries especially during the initial industrial phases. However, the excessive dependence might drag the company’s ability of innovation, which lead to a decrease in the long-term competitiveness in the market. This argument emphasizes that essential protection can lead to a developmental dependency when it is sustained. Therefore, while initial protectionism was beneficial for China’s trade growth, the continuous of openness became essential in the long-term [4].

However, Canada’s dependence on the US market illustrates how changes in external trade policy may cause unstable economic system. Due to the reliance that Canada has on the US market, it increases the uncertainty for Canadian exporters. Protectionism frequently endures for electoral motivations rather than economic rationale. The political election in the US becomes a motivation for further development of protectionism, and this action may sustain despite the negative inefficiencies. The bargaining power in international negotiations will grow since the country is frequently implementing trade barriers rather than to enhance efficiency, which shows that protectionism can serve as a strategic instrument in geopolitical maneuvers.

The actual consequences of these theories in the Trump era illustrate that unilateral tariffs at China cause retaliation, disruption in supply chains, and reduction in the global trade volume. This consequence shows that the extensive impact of modern protectionism is beyond national boundaries [5]. Those perspectives together reflect that, although protectionist policies may fulfill short-term economic or political objectives, they sometimes reduce economic efficiency, increase global volatility, and require careful adjustment to prevent permanent damage.

3. The impact of protectionism on China

Global trade took a severe hit when the United States started an intense commercial conflict against China during the Trump administration. China faced immediate trade consequences due to US tariff imposition upon $360 billion worth of Chinese exported products, while operating as the second-largest economy in the world. These trade barriers served two purposes, that they intended to decrease the US-China trade imbalance and make China revise its industrial methods and strengthen its protection of intellectual property. China’s high-tech manufacturing sectors faced crucial challenges, because sectors like electronics, telecommunications and automotive components took the greatest blow.

For many decades, Chinese exports demonstrated a constant growth trend, but they later faced a major decline. The World Bank reports that Chinese exports saw a 9.9% growth in 2018, while they dropped to 0.5% in 2019. Foreign companies operating in China are reevaluating their supply chain management, because many of them are moving manufacturing operations to Southeast Asia to avoid tariffs. China’s global industrial network position had begun to disperse, leading to reduced economies of scale.

China enacted multiple strategies to combat foreign trade conditions. Through this countermeasure, China targeted US import goods worth $110 billion with special emphasis on agricultural products including pork and soybeans. The Chinese government introduced domestic economic support through two initiatives, which provided tax advantages to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and increased spending on infrastructure to stabilize economic conditions [6]. China’s monetary policy flexibility rested on two key actions by the People’s Bank of China, including adjustments of reserve requirements and support for bank liquidity levels.

In 2020 China executed the “Dual Circulation Strategy” as a major initiative to decrease foreign demand dependency. The policy supports “internal circulation” strategies combined with local purchasing power growth and national research and development programs to develop independent supply chain systems, together with “external circulation” techniques, which preserve international trade access. The model represents China’s major economic restructuring to protect its economy in global disruptions and preserve its economic development speed.

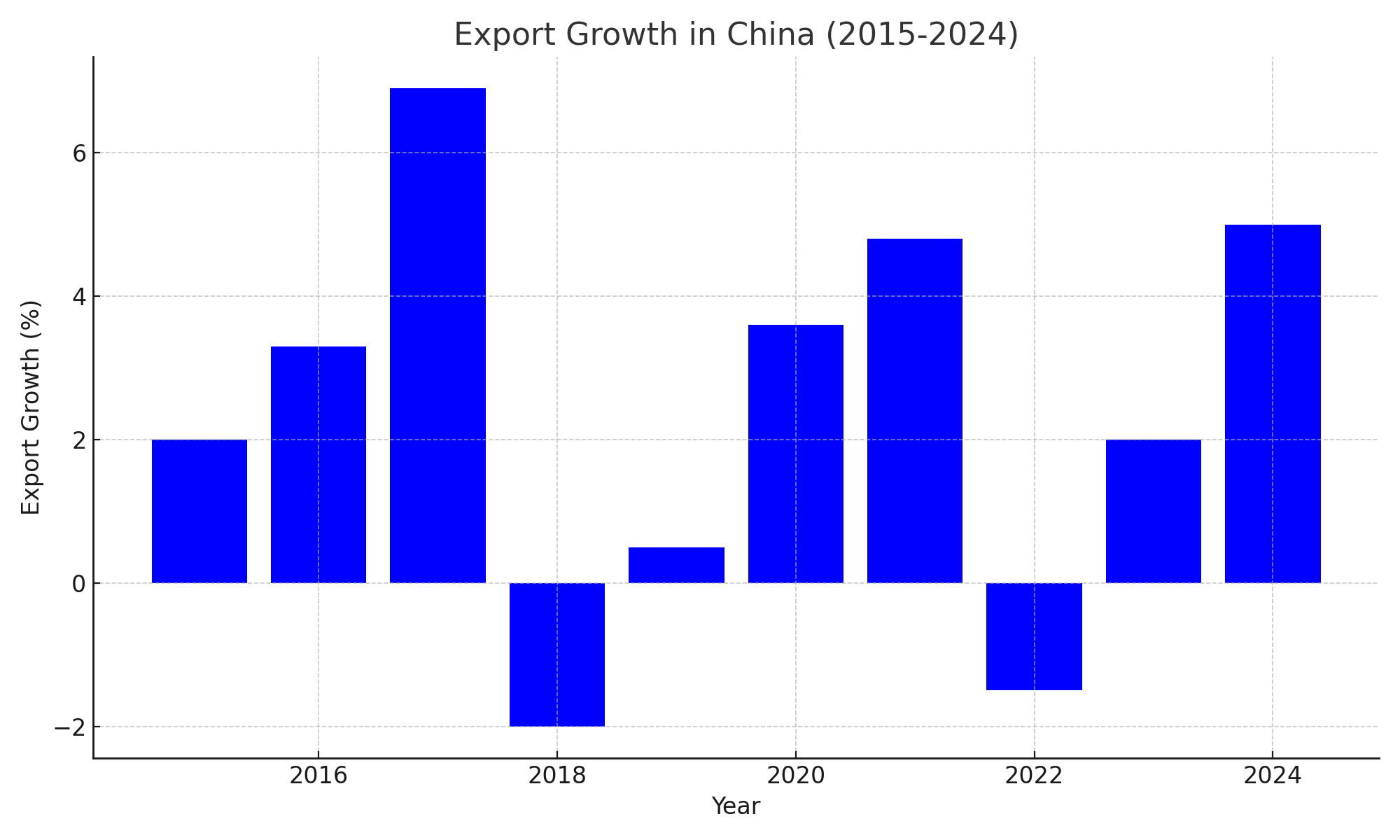

Figure 1: Export growth in China (data from: global trade alert and international monetary fund staff calculators)

China expanded its economic interests by creating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in 2020, which formed the largest trading bloc worldwide. China works to build a trade system that combines countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) with South Korea and Japan to reduce their trade dependence on Western economic zones. Through these steps, China seeks to reduce initial impacts from US protectionism, yet they also demonstrate permanent shifts toward new trading patterns between nations.

Figure 1 illustrates China’s export performance development across the six-year period from 2015 to 2024. The data tracks foreign trade results that experienced a significant decrease in 2018 following the introduction of protectionist regulations. The export expansion for China demonstrated positive recovery after a temporary phase of negative growth throughout 2021 and 2024.

China reacts to protectionist forces with a combination of economic strength alongside industrial policies and strategic international changes. Although the trade war brought immediate economic challenges, it caused China to implement structural changes creating both economic independence and extended global competitive advantages.

4. The impact of protectionism on Canada

Protectionist trade policies affect Canada’s economy through strong impacts, mainly because it depends on the United States for most of its exports. Canadian exports amount to about 75% of the total US market, thus, any American trade policy changes will have significant economic consequences across numerous industrial sectors in Canada. The economic partnership between Canada and the US reached an extreme point in 2018, following US implementation of Section 232 tariffs against Canadian steel and aluminum imports [7]. According to the US government, the tariffs against Canada were established for national security purposes, although Canada maintains a longstanding friendly relationship with the US.

Canadian industries experienced instant severe economic disturbances as a direct result of the tariff implementation. Manufacturing suffered serious damage when thousands of plant positions became endangered, since this sector depended on these materials extensively. The Canadian Steel Producers Association confirmed that steel industry workers would face job loss risks reaching 23,000 positions, while the industry sustained annual revenue deficiencies of $1.7 billion. The large magnitude of data illustrates that Canadian economic exposure grows as its dominant commercial relations endure arbitrary treatment from its major business counterpart.

The Canadian government organized multiple defensive economic measures against US tariffs to preserve its national economic security. The government of Canada set up $16.6 billion in trade barriers specifically aimed at US export items originating from districts where politicians had sensitive electoral interests. The Canadian trade restrictions targeted whiskey products among others, including orange juice, ketchup and household appliances, because these items created maximum political impact, even as they spared local domestic consumers from economic strain. Through its targeted trade measures, Canada practiced protective economic tactics, which showed its will to defend economic authority, yet proved the minimal impact of its economy against the larger economy of the US [8].

New trade uncertainties intensified after the countries started negotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), but the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) became a consensus. The lengthy USMCA negotiations produced market uncertainties that harmed business investment choices, along with damaging US diplomatic relationships. The escalating trade tensions between the US and Canada forced these Canadian industries working in vehicles and farms to display increased caution about capital investment initiatives. Future trade agreements became uncertain, because businesses worried about unexpected changes in the direction of US political power.

Figure 2 below demonstrates how Canadian exports evolved during the time period from 2015 to 2024. The data reveals export expansion patterns throughout the period which experienced extensive decreases during 2018 due to protective trade approaches. Canada achieved a recovery in exports during 2021, with continuing growth expected in 2024 despite past periods of negative growth.

Figure 2: Export growth in Canada (data from: global trade alert and international monetary fund staff calculators)

The Canadian government has launched plans to decrease its dependence on American trade because of existing market obstacles. The 2018 ratification of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) made new opportunities available to Canada across Asia and Latin America, so the nation expanded its economic possibilities. The European Union gave Canadian exporters access to 500 million consumers through its Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). Canadian SMEs face challenges when adjusting to new regulatory systems and extra competition from foreign players.

The prevalent US-Canada geographical relations, as well as extensive economic and cultural ties create barriers for Canada to break all connections completely. The country faces ongoing exposure to US trade policy changes, especially within three important industries, namely, dairy farming, lumber production and auto production.

Canada learn that protectionism creates a basic structural weakness because of their trading relationships. The current economic structure of Canada remains unchanged by retaliatory tariffs or diversification agreements, because these instruments only provide limited defensive capabilities [9]. To create a lasting sustainable strategy, Canada needs to build innovation locally, while becoming more competitive and developing resilience which requires international collaborations. This method reduces the negative effects of global trading conditions while building Canadian economic resilience for worldwide collaboration.

5. Comparative analysis and policy recommendation

Due to variations in their economic frameworks and market orientation levels, the United States protective trade policies motivated China and Canada to choose separate actions. Both China and Canada used different approaches to US trade restrictions, while China prioritized domestic resources together with diplomatic developments, and Canada worked on boosting international market reach through international dialogue.

Industrial subsidies from China served as the main strategic solution, along with foreign trade restrictions and international expansion through RCEP and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The government-mandated “Dual Circulation Strategy”, aiming to establish national independence combined with innovative economic growth. Through these measures China has become more able to operate independently from Western influence, while making its economy less exposed to West-based market disturbances [10]. The Chinese economy has expanded its market authority, because it transfers its production facilities and investment capital to diverse global markets to reduce political trade uncertainty.

Canada became more vulnerable to market changes because its dependence on US export markets combined with tightly linked energy and automotive supply chains. The US trade tariffs and NAFTA renegotiations prompted Canadian officials to create two strategic reactions through retaliatory trade measures and signing agreements, such as CPTPP and CETA, for market diversification. Canada’s use of careful trade policies through retaliatory measures failed to achieve short-term success because of its extensive trade dependency with the United States. Canada’s small-scale domestic market reduces its ability to protect its economy by focusing on internal growth like what China currently accomplishes.

China implements better institutional foundations to take definitive actions, and all nations understand the urgent need to reduce their dependence on external connections. The combination of market liberalism, democratic policies and federal governance structures naturally produce economic transformation delays in Canada. People worldwide endorse the need for countries to develop economic power without embracing total isolationism as trade barriers continue to expand.

China should consider emphasizing the preservation of intellectual property rights to attract foreign investment and ensure sustainable innovation. Developing commercial hyperlinks with non-Western and unconventional markets could reduce economic dependence on the US and European countries. Strategies that involve the “Dual Circulation Strategy” should continue in enhancing domestic demand, while national research and development programs can further boost industrial independence and technological growth. China’s proactive efforts in establishing regional alliances, represented by the RCEP, indicating a sustainable path toward global economic leadership through collaborative trade frameworks rather than isolationism.

The Canadian government should prioritize the development of financial incentives that encourage SMEs to examine markets outside the US, thereby diminishing susceptibility to fluctuations in US trade policies. Enhancing provincial supply chains and expanding financing for research and development will boost domestic resilience, particularly in sectors vulnerable to external tariffs such as steel and automotive. Furthermore, Canada ought to push for reforms in global trade governance via international organizations like the World Trade Organisation. This will ensure equitable involvement between national safeguarding initiatives and international cooperation, aiding in ensuring the stability of Canada’s financial situation in a fluctuating global trade landscape.

6. Conclusion

An assessment of protectionist policies demonstrates how China and Canada adopted different methods to handle US protectionist challenges. The centralized economic design and strategic planning methods along with China’s large domestic market let the country establish effective approaches to handle tariff problems. Chinese economic policy now adopts the “Dual Circulation Strategy”, because the central government wants to build domestic strength and independence as the protection from international political disturbances. China has shown its global economic strategy through RCEP to strengthen market dominance in non-Western territories and defend its economic position.

Canadian economic performance heavily depends on the US market, which creates an unsafe condition. The level of trade connection between countries generates fundamental uncertainties, which slow down Canada’s ability to efficiently manage protectionist measures implemented by others. The retaliatory tariffs, along with diversification plans, demonstrate pragmatic responses to market shifts, but the extensive trading relationship with the US limits Canada’s long-term protection against protective measures. Temporary trading interruptions create economic instability, affecting business sectors and collective staff, as well as investment debt and capital flow uncertainty.

The two nations face major issues regarding trade protectionism implementation while markets undergo changes. Economic stability needs development by government authorities from both nations, avoiding strict isolationist approaches. The long-term prosperity of China depends on technological advancement, together with sustainable approaches and global economic cooperative agreements. The Canadian government must offer financial support to local SMEs to create local supply networks and fund their innovative growth through targeted funding methods to maintain economic stability from disrupted foreign business operations. International protectionist policies currently outnumber every other form of global trade policy, leading to a requirement for modifying official trade management systems. The international cooperation framework demands China and Canada to develop solutions which bind national preservation programs with global partnership responsibilities.

References

[1]. Beaulieu, E., Leblond, P., Klemen, D., Cock, J., Dubuis, T., Vautour, C., & Vinod Kelly Daryanani, N. (2019, November 15). The Future of Canadian Trade Policy: Three Symposia on Canada’s Most Pressing Trade Policy Challenges. Social Science Research Network

[2]. Béland, D., Dinan, S., Rocco, P. and Waddan, A. (2021) Social policy responses to COVID‐19 in Canada and the United States: Explaining policy variations between two liberal welfare state regimes. Social Policy & Administration, 55(2), 280-294.

[3]. Dadush, U. (2023) American Protectionism. Revue d’Économie Politique, Vol. 133(4), 497–524.

[4]. Dadush, U. (2023) American Protectionism. Revue d’Économie Politique, Vol. 133(4), 497–524.

[5]. Guilherme, V. (2024) Shaping Nations and Markets, Identity Capital, Trade and the Populist Rage. London: Routledge.

[6]. Guo, J. and Johnston, C. M. T. (2020) Do protectionist trade policies integrate domestic markets? Evidence from the Canada-U.S. Staff Working Paper 2020-10, 2020, 1–20.

[7]. Huysmans, M. (2020) Exporting protection: EU trade agreements, geographical indications, and gastronationalism. Review of International Political Economy, 29(3), 1–28.

[8]. Olha, Y., Stašys, R., Tsygankova, T., Reznikova, N. and Uskova, D. (2021) Protectionism Sources of Trade Disputes within International Economic Relations. Management Theory and Studies for Rural Business and Infrastructure Development, 42(4), 516–526.

[9]. Van Assche, A. and Gangnes, B. (2019). Global Value Chains and the Fragmentation of Trade Policy Coalitions. Transnational Corporation, 26(1), 31-60.

[10]. Williams, N. (2019). The Resilience of Protectionism in U.S. Trade Policy. Boston University Law Review, 99, 683-719.

Cite this article

Chen,D. (2025). Protectionism in Modern Economic System: Evaluating the US Trade Policies and the Impacts on China and Canada. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,97,6-12.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceeding of ICGPSH 2025 Symposium: The Globalization of Connection: Language, Supply Chain, Tariff, and Trade Wars

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Beaulieu, E., Leblond, P., Klemen, D., Cock, J., Dubuis, T., Vautour, C., & Vinod Kelly Daryanani, N. (2019, November 15). The Future of Canadian Trade Policy: Three Symposia on Canada’s Most Pressing Trade Policy Challenges. Social Science Research Network

[2]. Béland, D., Dinan, S., Rocco, P. and Waddan, A. (2021) Social policy responses to COVID‐19 in Canada and the United States: Explaining policy variations between two liberal welfare state regimes. Social Policy & Administration, 55(2), 280-294.

[3]. Dadush, U. (2023) American Protectionism. Revue d’Économie Politique, Vol. 133(4), 497–524.

[4]. Dadush, U. (2023) American Protectionism. Revue d’Économie Politique, Vol. 133(4), 497–524.

[5]. Guilherme, V. (2024) Shaping Nations and Markets, Identity Capital, Trade and the Populist Rage. London: Routledge.

[6]. Guo, J. and Johnston, C. M. T. (2020) Do protectionist trade policies integrate domestic markets? Evidence from the Canada-U.S. Staff Working Paper 2020-10, 2020, 1–20.

[7]. Huysmans, M. (2020) Exporting protection: EU trade agreements, geographical indications, and gastronationalism. Review of International Political Economy, 29(3), 1–28.

[8]. Olha, Y., Stašys, R., Tsygankova, T., Reznikova, N. and Uskova, D. (2021) Protectionism Sources of Trade Disputes within International Economic Relations. Management Theory and Studies for Rural Business and Infrastructure Development, 42(4), 516–526.

[9]. Van Assche, A. and Gangnes, B. (2019). Global Value Chains and the Fragmentation of Trade Policy Coalitions. Transnational Corporation, 26(1), 31-60.

[10]. Williams, N. (2019). The Resilience of Protectionism in U.S. Trade Policy. Boston University Law Review, 99, 683-719.