1. Introduction

The ancient civilisations of the Mayans and Incas not only left behind architectural and archaeological wonders, but they also preserved these ideas by converting their beliefs, values, and understanding of the universe into symbols and hieroglyphics that they carved, painted, and etched on stone, ceramics, and textiles. These symbols are more than just a means of communication[1]. They are also profoundly spiritually and culturally essential instruments, reflecting a social worldview intricately linked to the natural and supernatural realms. For the Maya civilization, hieroglyphs constituted a sophisticated amalgamation of linguistic elements, mythological narratives, astronomical observations, and ritualistic practices, offering profound insights into the cyclical nature of time and the divine authority to comprehend and govern the phenomena of life and death. Similarly, Inca symbols - although their written language was based mainly on hieroglyphics rather than hieroglyphics - conveyed a sacred relationship with the sun, moon, mountains, and elements, reinforcing the centrality of nature in their view of the universe. This manuscript posits that by examining these symbols, contemporary scholars and their successors can access ancestral knowledge and elucidate the profound spiritual philosophies that influenced these civilizations.

2. Mystical symbols of the maya

2.1. Structural and religious semantic analysis of maya hieroglyphics

As one of Central America's most glorious ancient civilizations, the Mayan civilisation has left behind a rich cultural heritage, among which the most fascinating is undoubtedly its hieroglyphic system. These symbols are not only language tools, but also sacred and mysterious images, embodying the profound connection between the Mayans and the universe, deities and the earth. These hieroglyphs show how the Mayans viewed the world, explained life and death, conversed with nature, understood deities, and conveyed philosophy through images.

2.2. The artistic and ideological integration of hieroglyphics

Mayan hieroglyphics were not merely used to record language; they were a visual philosophy and totems brimming with a sacred air. [2] Every symbol and every image may contain a complete concept or story. As described in the text, these "glyphs" are not merely "characters", but "figures", the dynamic images of faces, eyes, hands and feet, as if they were the incarnations of deities.

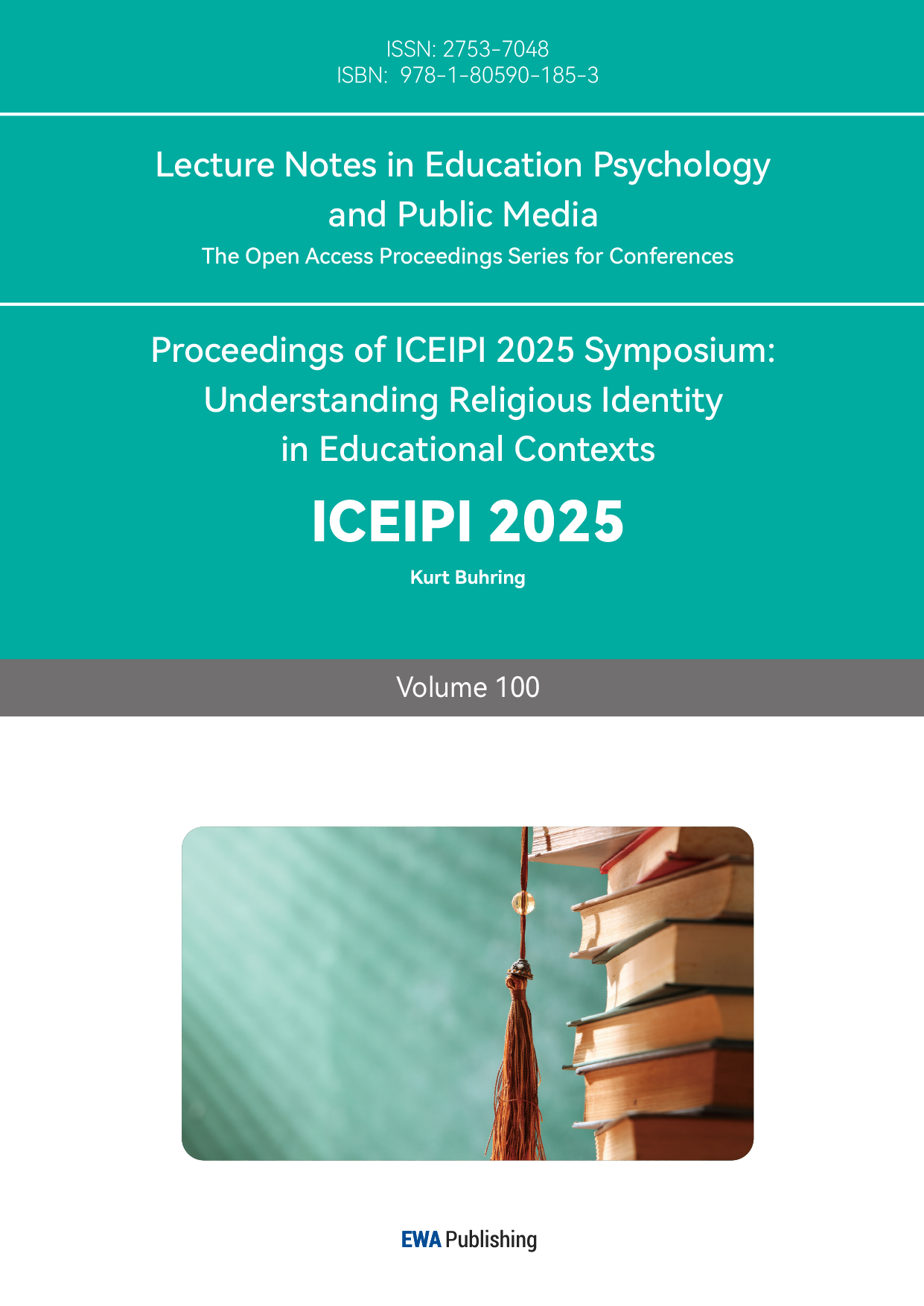

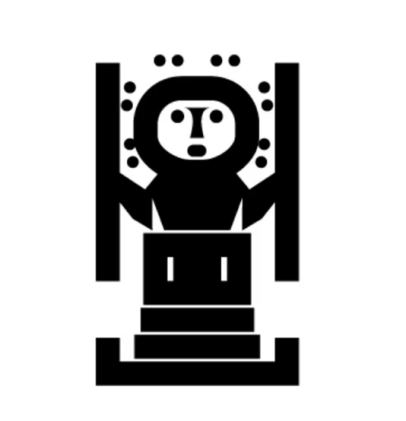

Mayan hieroglyphs integrate art and thought, enabling information transmission and conveying religious and philosophical symbolism. For instance, the earth crocodile representing "Imix" (Figure 1) symbolizes Mother Earth, a cosmic force embodying solar consumption and regeneration. Words, as a form of "sacrifice," mediate deity-human communication.

2.2.1. Understanding of deities and the universe

The Mayans regarded the universe as a dynamic and cyclical whole, brimming with the power of the unity of opposites. Hieroglyphics are precisely the concrete manifestation of this worldview. They believe that mystery is not unknowable but part of reality. As the text says: "For the Mayans, mystery is the cyclic reality of an ever-changing universe..." This indicates that their understanding of the universe is nonlinear. Time is not a straight line but an eternal cycle of reincarnation.

The Sun God (God D) was devoured by "Imix" at dusk and rose from its fangs at dawn. This image elucidates the diurnal cycle and conveys an understanding of the life-death continuum. [2] This mythologized expression of daily natural phenomena has been passed down for thousands of years through hieroglyphics. It has also established the core spirit of the Mayan religion: revering nature and conforming to the will of heaven.

2.2.2. Religious belief structure in hieroglyphics

Mayan hieroglyphics also profoundly reflect their religious system's structure and symbolic meaning. In Popol Vuh and The Book of Chiran Baran, the Earth is imagined as a powerful monster, and its image even has the head of a dragon and the magic of a crocodile. In different mythological versions, the image of the Earth god keeps changing. Still, they all embody the combination of nature and divine power and the sacredness of the formation of heaven and earth.

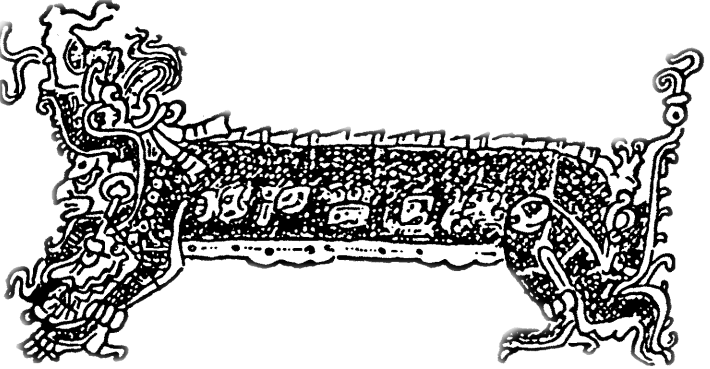

The four-sided god "Bacab" and its corresponding four-colored crocodile image (red, white, black, and yellow) (Figure 2) represent the four directions of the universe. [3] They possess not only geographical significance but also ritual and symbolic meanings, embodying the "sacred image language" of Mayan culture through the concretization of abstract directions into deities and symbols.

2.3. Hieroglyphics serve as symbols of fate and protection

The Mayans believed that hieroglyphics could change destinies and prevent evil and disasters. Beyond inscriptions and writing, they were also engraved on stone tablets and painted on codices, functioning as religious rituals and amulets. Every symbol bears the trace of divine power and serves as a bond connecting deities and mortals. These words were not only used to record myths, but also widely used in calendars and sacrificial ceremonies, such as the "Long Count" and the "Tzolk'in", etc. Mayan hieroglyphics facilitated the scheduling of sacrifices, prediction of astronomical events, and determination of agricultural timing, thus underscoring their indispensable role in social life.

2.4. Influence on future generations and the continuation of cultural heritage

Although many Mayan manuscripts were burned during the Spanish colonial period, and Mayan hieroglyphics were once forced to be interrupted, their cultural and spiritual power did not die out. [4] Modern archaeologists and linguists have gradually deciphered these characters by studying documents such as the Dresden Codex, enabling us to re-understand this forgotten civilization today.

Mayan hieroglyphics have left a precious cultural heritage for future generations. It is an important resource for archaeological research and provides a basis for the modern Mayans to re-identify with their own culture. Among the contemporary Mayans on the Yucatan Peninsula, some continue their ancestors' beliefs in the form of totems and symbols. It reminds us that language is not merely a communication tool, but also the root of culture and how a nation's spirit is carried forward.

2.5. Seeing the soul through images

Mayan hieroglyphics are not cold symbolic systems but a vibrant cultural expression. It embodies a mythological lexicon, a marginal annotation to the terrestrial and celestial spheres, and humanity's laudatory hymn to the enigmatic cosmos. Reading Mayan hieroglyphics is like having a dialogue with ancient wisdom. It is also a kind of spiritual cultivation - as the text says: "You need to view them like a child, with patience, kindness and faith, to learn to 'see' in your dreams."[5]These words represent not only the past glories, but also a civilization's inquiry and inheritance of eternal truth. Just as the sun rose and set in the crocodile's mouth, Mayan hieroglyphics vanished from history and were "seen" again today, still shining brightly and meaningfully.

3. Mystical symbols of the inca

3.1. "Structural and religious semantic analysis of inca hieroglyphics"

Although the Inca civilization and the Mayan civilization both belonged to the ancient cultures of Central and South America, there were significant differences in the development of hieroglyphics. Unlike the highly developed hieroglyphic system of the Mayans, the Incas did not create a proper hieroglyphic system. They use a knot-keeping system called Quipu, which conveys information through the knots' position, color, quantity and shape. This system was used primarily for administrative management, population statistics and agricultural production records, reflecting the Incas' powerful organizational ability and mathematical concepts. Although Kip is not a traditional "hieroglyphic", it still reflects the unique worldview and cosmic order of the Incas. Inca civilization manifested its reverence for deities, including Inti and Pachamama, via oral traditions, patterns, symbols, and architecture. The Inca "writing" system integrated practical functions with sacred beliefs, epitomizing a unique civilized expression and underscoring the diversity of human civilization.

3.2. Symbolic "word" system: the evolution from graphics to faith

Unlike the Mayan civilization, which used complex hieroglyphics, the Incas mainly used Quipu for administrative and quantitative record-keeping. Although this system based on lines and knots does not have the function of figurative writing, it is a convenient means of symbolic memory. Furthermore, in art forms such as architecture, pottery, textiles, and gold and silver wares, the Incas developed highly symbolic graphic symbols to express religious images and worldviews.

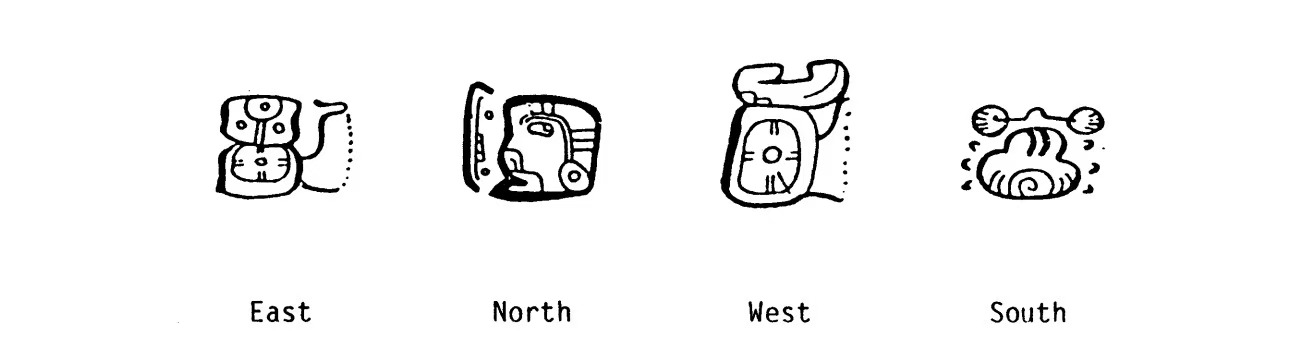

The most representative symbol is the [6] Chakana (Figure 3), also known as the "Inca Cross" or "Andean cross". The stepped cross pattern, prevalent in Inca and pre-Inca cultures, embodies the Inca cosmology, reflecting their understanding of the universe, morality, divine hierarchy, and spiritual progression[7].

Chacana symbolizes the three-tier world structure of the universe:

(1)Hanan Pacha (Upper Realm) : The celestial world where the sacred vulture represents stars, gods and ancestral souls.

(2)Kay Pacha (Middle World): The real world, where humans survive, is represented by the cougar, symbolising power and survival.

(3)Uqhu Pacha (Lower Realm) : The Netherworld and the land of the dead, guarded by the snake representing wisdom and rebirth.

The three steps at the four corners of Chacana also represent the moral principles of the Incas: "Ama sua (do not steal), Ama llulla (Do not lie), Ama quella (Do not be lazy)". These three principles are the cornerstones of the entire Inca social order and religious beliefs.

3.2.1. The view of the origin of the universe in myths and symbols

The Inca cosmology combines the worship of nature and the reverence for anthropomorphic deities, with the core deity being the creator god [8] Viracocha. He is both the creator of the world and humanity, and a cultural disseminator and educator. He originated humans, destroyed and recreated them from stones, scattering them in all directions, embedding a concept of cyclical rebirth within Inca religious symbols.

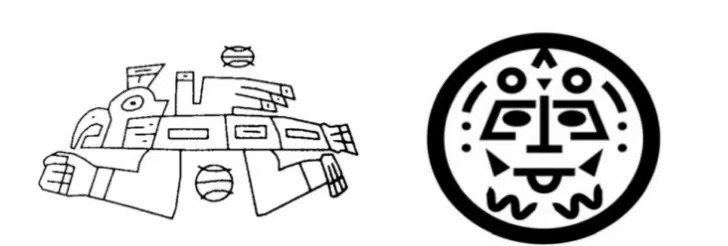

Villakocha( Figure 4) is often depicted as a bearded man in a long robe, and is even called "the Old Man of Heaven" or "the World's Mentor". His image often appears in the murals or sculptures of temples. [9]He also served as Pachacuti's patron saint, mirroring the church-state unity through the symbolic union of gods and kings.

In addition, deities related to celestial bodies also played an important role in Inca religion:

Inti: The sun god, regarded as the ancestor of the Inca royal family, symbolizes light, warmth and the hope of farming. His image is a human face embedded in a radiant disc, symbolising the Inca state.

Mama Quilla: The moon goddess, in charge of time, the female cycle and festival rituals, symbolizing the power of silver and tenderness.

Illapu: The god of rain. Believers often pray to him for rain during droughts, symbolizing the connection between celestial bodies and the earth.

Pachamama: Mother Earth, symbolizing abundance, nurturing and protection, is one of the most revered deities in agricultural rituals.

These deities do not exist in isolation but interact with humans through rituals, totems, terrain layouts and festival cycles, forming a sacred ecosystem where humans, nature, and deities are interdependent.

The former Inca deity [10] Pacha Kamaq (Figure 5)embodies the integration of ancient mythology and nature worship. Though his stature is secondary to Viracocha, the deity known as "Land Creator" embodies the dichotomy of creation and destruction through the mythic narrative of food neglect and subsequent marine exile, thus underscoring the ocean's significance in the Inca's natural cosmology.

3.2.2. Totems and sacred objects: visual language in religious ceremonies

The Inca civilization utilized sacred iconography, including totems, masks, and textile motifs, to express religious concepts. Each totemic animal, such as the puma, snake, and vulture, symbolized specific realms and deities. Furthermore, ritual artifacts like sun masks and precious metal face carvings were integral to temple ceremonies, functioning as conduits between the human and divine spheres.

Festival celebrations and human sacrificial ceremonies also rely heavily on these symbols. The temples of the rain god Ilap are often built in high places, where people perform activities such as praying for rain, making human sacrifices, and dancing. These rituals are not merely superstitions but an embodiment of a cosmology - to reconcile the three realms of heaven, earth and man through symbolic acts and achieve a balance between nature and society.

3.3. Influence on later generations and spiritual inheritance

Although the Spaniards conquered the Inca Empire in the 16th century and destroyed many temples, relics and records, the spiritual core of Inca culture did not completely die out. The Chacana, as a spiritual emblem, persists within the Andean region, finding contemporary application among indigenous communities in ornamentation, ceremonial observances, supplications, and the assertion of cultural identity.

In today's Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador, many indigenous people still celebrate traditional festivals centered on the sun, the moon and the earth, such as [11] Inti Raymi, a modern iteration of ancient Inca religion, and the Inca's nature-worship ideology, have spurred ecological movements and sustainable development. Mythological figures like Velacocha, imbued with new symbolic meanings, inspire modern art and literature. The Chakana's spiritual essence symbolizes the enduring nexus between human intellect and nature.

Although the Inca civilization did not have a traditional hieroglyphic system, it constructed a unique religious and philosophical expression system through totems, images of deities, architectural layouts, textile patterns and mythological legends.These symbols represent humanity's exploration of world order, social norms, natural forces, and spiritual realms beyond mere religious iconography. Inca "visual language" demonstrates that true "writing" extends beyond conventional script, encompassing mountains, masks, rituals, and human-nature communication. For this reason, the spiritual heritage of Inca culture, having traversed the long river of time, still echoes in the wind and stars of the Andes Mountains to this day.

4. Discussion

The hieroglyphics of the Mayan civilization profoundly demonstrated its religious belief system, with myths, celestial phenomena, nature and the cycle of life as the core. For example, the rise and fall of the sun god symbolized the cycle of life and death. Even in the absence of a codified hieroglyphic system, the Inca civilization engendered a cosmology integrated with the tripartite division of the cosmos—the celestial sphere, the terrestrial domain, and the subterranean realm—through symbolic representations including the Chakana, divine totems, and architectonic configurations. It combined nature worship (such as the sun god Inti and the earth mother Pachamama) to reflect the interactive relationship between humans, nature, and deities.

Mayan hieroglyphics were used in calendars (such as the Tzolk'in sacred calendar), sacrificial ceremonies and prophecy systems, as an essential tool for connecting humans and gods, determining sacrificial times and interpreting the mandate of heaven. The symbolic signs of the Inca play a core role in festivals, human sacrifices and rain-praying ceremonies. For instance, the construction and sacrificial rites of the Ilap Temple demonstrate their reverence for natural forces and reliance on rituals.

The Mayan script represents an integration of artistic expression, mythological narratives, calendrical systems, and philosophical concepts, embodying a synthesis of written language, totemic representations, and sacred iconography. Inca culture deeply integrated graphic language into social norms, spiritual morality (such as the three commandments of "no stealing, no cheating, and no laziness") and the national governance system, demonstrating a high level of social order and cosmic morality.

Although the Mayan hieroglyphics were extensively burned down during the Spanish colonial period, some were preserved through documents such as the "Dresden Documents", becoming the key for modern people to understand the ancient Mayan religion, cosmology and philosophy. The Inca's Chacana symbols, divine myths, and ceremonial traditions persist among the Andean populace, forming ethnic identity and spiritual foundations, and galvanizing contemporary ecological ideology and cultural resurgence.

5. Conclusion

Through a systematic analysis of the hieroglyphics and religious symbols of the Mayan and Inca civilizations, this study reveals how ancient American civilizations conveyed profound religious beliefs, cosmic cognition and social norms through visual symbol systems. Mayan hieroglyphics are not only a recording tool, but also an expression system that integrates images, language and sacred beliefs. Each "script" carries a cosmology and holy significance. Conversely, lacking a developed writing system, the Inca established a comprehensive visual language via Chacana, temple layouts, pottery totems, and festival symbols, representing the triadic structure of realms, the universe, and moral tenets. Although the two civilizations have different forms of expression, the core of both lies in constructing communication Bridges between humans and nature, as well as deities through symbolic means, thereby maintaining social order. This article points out that these symbols embody the visualization of religious ceremonies and reflect the governance model where politics and religion are highly integrated. Although temporal attrition has obscured certain symbols, contemporary archaeological, linguistic, and ethnological investigations have facilitated the recovery of their profound significances. These symbols have been reintegrated into the cultural identity and ecological values of modern Latin American indigenous populations, thereby perpetuating the spiritual legacy of human inquiry into the cosmos and the quest for equilibrium.

References

[1]. Luxton, R. (1981). The mystery of the Mayan hieroglyphs: The vision of an ancient tradition. New York: Harper and Row.

[2]. Portilla, L. (1973). Time and reality in the thought of the Maya. Boston: Beacon Press.

[3]. Borak, M. -L. (1987). Specialization written research paper: The Mayan hieroglyphs: Mystery and reality. Art Department, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

[4]. Roys, R. (1965). The ritual of the Bacabs. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

[5]. Pérez, C. (1949). Book of Chilam Balam of Mani. In E. Solis Alcala (Trans. ). Mérida.

[6]. Gullberg, S. R. (2020). Astronomy of the Inca Empire: Use and significance of the sun and the night sky. Springer Nature.

[7]. Kolata, A. (1993). The Tiwanaku: Portrait of an Andean civilization. Cambridge: Blackwell.

[8]. Viau-Courville, M. (2014). Spatial configuration in Tiwanaku art: A review of stone carved imagery and staff gods. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, 19(2), 15–16.

[9]. Stübel, A. , & Uhle, M. (1892). Die Ruinenstätte von Tiahuanaco im Hochlande des alten Perú: Eine kulturgeschichtliche Studie auf Grund selbständiger Aufnahmen. Leipzig: Hiersemann.

[10]. Prescott, W. H. (2011). The history of the conquest of Peru. DigiReads Publishing.

[11]. Laime Ajacopa, T. (2007). Diccionario bilingüe: Iskay simipi yuyayk’anch: Quechua – Castellano / Castellano – Quechua (PDF). La Paz, Bolivia: futatraw. ourproject. org.

Cite this article

Yang,H. (2025). Hieroglyphics and Symbols of the Mayan and Inca Civilizations: Exploring Their Culture, Religion. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,100,135-143.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of ICEIPI 2025 Symposium: Understanding Religious Identity in Educational Contexts

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Luxton, R. (1981). The mystery of the Mayan hieroglyphs: The vision of an ancient tradition. New York: Harper and Row.

[2]. Portilla, L. (1973). Time and reality in the thought of the Maya. Boston: Beacon Press.

[3]. Borak, M. -L. (1987). Specialization written research paper: The Mayan hieroglyphs: Mystery and reality. Art Department, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

[4]. Roys, R. (1965). The ritual of the Bacabs. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

[5]. Pérez, C. (1949). Book of Chilam Balam of Mani. In E. Solis Alcala (Trans. ). Mérida.

[6]. Gullberg, S. R. (2020). Astronomy of the Inca Empire: Use and significance of the sun and the night sky. Springer Nature.

[7]. Kolata, A. (1993). The Tiwanaku: Portrait of an Andean civilization. Cambridge: Blackwell.

[8]. Viau-Courville, M. (2014). Spatial configuration in Tiwanaku art: A review of stone carved imagery and staff gods. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, 19(2), 15–16.

[9]. Stübel, A. , & Uhle, M. (1892). Die Ruinenstätte von Tiahuanaco im Hochlande des alten Perú: Eine kulturgeschichtliche Studie auf Grund selbständiger Aufnahmen. Leipzig: Hiersemann.

[10]. Prescott, W. H. (2011). The history of the conquest of Peru. DigiReads Publishing.

[11]. Laime Ajacopa, T. (2007). Diccionario bilingüe: Iskay simipi yuyayk’anch: Quechua – Castellano / Castellano – Quechua (PDF). La Paz, Bolivia: futatraw. ourproject. org.