1. Introduction

The public recognizes the role of emojis as a way of communication. Emojis have been indispensable and efficient tools in online interaction with the booming Internet and dramatically fast emergence of electronic communication channels. [1] A growing body of literature recognizes the importance of the link between the preference for emojis and people's age. Digital footprints of people's language usage in social media posts were found to allow for their age and gender inferences. [2] Emojis have been a significant area of interest within the field of linguistics. In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in the controversies of the feelings about emojis, which is common for people of different ages. Of particular concern is that until now, the research on people of different ages have different preferences for emojis are not much. Thus, it is hard to explore the link between the preference for emojis and people's age.

Recent evidence suggests that there are some different preferences of people from different age groups. Regarding linguistic differences with age, research indicates that older people use more positive emotion words (e.g., "happy"), fewer negative emotion words, like "angry", and fewer self-references, such as "me". [2] Hence, there are some differences between people of different ages when using emojis, namely their preference for emojis. One of the most significant current discussions on emojis is what are the differences in the preferences of people of different ages over the use of emojis? Most studies in emojis have only focused on proving differences in preferences of people of different ages. However, up to now, far little attention has been paid to exploring what the differences were. The central thesis of this paper is to analyze the differences in preferences for emojis among different age groups. Data for this study were collected by interviewing people of different ages. This work will generate fresh insight into the differences in the preferences of people of different ages over the use of emojis. But this study cannot encompass the effects of relevant age differences in emojis, such as the interpretation of emojis.

The overall structure of the study takes four parts; the first part is the studies in the past. The second part is concerned with the methodology used in this study. The third part focuses on the result of the study. The last part is about the discussion based on the outcome.

2. Literature Review

There are a lot of theories that can prove there are differences in preferences for emojis among different age groups. Although the literature covers various such theories, this review will focus on the conversational implicature theory. This theory provides semantic support for the difference in the preferences for emojis by different age groups.

Most studies of emojis were focused on interpretation. Susan C. Herring and Ashley R. Dainas argued that gender and age influence the interpretation of emoji functions. [3] Later, Jing Cui discussed the emoji-based sarcasm interpretation between younger and older adults. Current studies do not correlate well with preferences for emojis across age groups. [4] Very few studies on emojis are solely about age groups, and even fewer involve preferences.

Therefore, studying the preference for emojis by age groups can fill a gap in the field of emoji research regarding preference differences.

3. Method

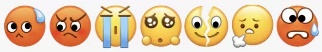

In this paper, I select eight emojis from Wechat (one of the famous Chinese social media) to analyze the different preferences for emojis across age groups. My interview questions are:

How do you feel about  and

and  ? What kind of emotion do they convey? Can you tell the difference between the two emojis, if so, what is the difference? Which one is usually used in your communication?

? What kind of emotion do they convey? Can you tell the difference between the two emojis, if so, what is the difference? Which one is usually used in your communication?

How do you feel about  and

and  ? What kind of emotion do they convey? Can you tell the difference between the two emojis, if can, what is the difference? Which one is usually used in your communication?

? What kind of emotion do they convey? Can you tell the difference between the two emojis, if can, what is the difference? Which one is usually used in your communication?

How do you feel about  and

and  ? What kind of emotion do they convey? Can you tell the difference between the two emojis, if can, what is the difference? Which one is usually used in your communication?

? What kind of emotion do they convey? Can you tell the difference between the two emojis, if can, what is the difference? Which one is usually used in your communication?

Which group of emoji are usually used in your communication? (preference)

Group A:  Group B:

Group B:

This interview set 4 questions, question 1-3 are mainly focus on different choice among two age groups, in order to figure out their preference on two emojis that convey the same emotion. (i.e., question 1 is two emojis showing cry; question 2 is two emojis showing embarrassment; question 3 is two emojis showing a smiling face. Question 4 is set two groups of emojis that separately the positive one and the negative one, the positive means that the emojis in that group showing the positive emotions, vice versa.

This interview set 4 questions; questions 1-3 are mainly focused on the different choices among two age groups in order to figure out their preference for two emojis that convey the same emotion. (i.e., question 1 is two emojis showing cry; question 2 is two emojis showing embarrassment; question 3 is two emojis showing a smiling face. Question 4 is set two groups of emojis, separately the positive one and the negative one: the positive means that the emojis in that group show positive emotions, and vice versa.

The interview questions are designed based on the theory of conversational implicature. Based on theoretical interviews, these questions were designed to allow respondents to associate emoji with the "implication" when describing their choice preferences.

I collected and analyzed the interviewees' answers and made Table 1. I make the conclusion in three aspects: feeling, positive/ negative and using frequency. The feeling part is the feelings of each emoji when interviewees see the emoji. The attitude part is distinguished by whether the emotions the emoji conveys are positive or negative. As for the using frequency part, I divide the frequency into "often" and "seldom".

4. Result

Table 1. Result of the interview.

Age | Feeling | Attitude | Using Frequency | |

| 10-30 | Feel wronged | Negative | Often |

31-50 | A cute crying face | Seldom | ||

| 10-30 | Crying sadly | Negative | Often |

31-50 | A crying face showing sadness | Seldom | ||

| 10-30 | Using when I did something inappropriate | Negative | Often |

31-50 | An embarrassment emoji | Seldom | ||

| 10-30 | Using when others did something awkward | Negative | Often |

31-50 | An embarrassment emoji | Seldom | ||

| 10-30 | An emoji indicates irony | Negative | Seldom |

31-50 | A friendly smiling face | Positive | Seldom | |

| 10-30 | A smiling face showing politeness | Positive | Seldom |

31-50 | A cute smiling face | Often |

5. Discussion

This interview indicates that people from 31-50 years old do not tend to use emojis that mean negative emotions, which is the same as the conclusion of Timo K. Koch et al. [2] Regarding linguistic differences with age, research suggests that older people use more positive emotion words (e.g., "happy"), fewer negative emotion words, like "angry". [2] Some are concerned that it is a stereotype that older people are friendly. However, this "stereotype" is not an unfounded inference. The conclusion of Jing Cui proves it. An ordering and sequencing principle—"precedence of the old over the young"—emphasizes a communication pattern that older people should be loving and friendly and the younger should be pious and respectful. [4] This conclusion also corresponds with the opinion that older people tend not to use emojis that convey negative emotions.

Because they are showing love and friendliness when communicating. In question 4, all the people over 30 prefer emojis in Group A. Both interviewee five and interviewee 6 are aware of the distinction between Group A and Group B. They mentioned a similar opinion that the emojis in Group A convey negative emotions and those in Group B convey positive emotions. What is more, Interviewee 5 put forward the idea that he does not want to show his negative emotions to others, especially unfamiliar people. Hence, he seldom uses emojis in Group B. He also added an interesting interpretation of the reason why he rarely uses emojis that indicate negative emotions. He thinks that one salient feature of Chinese is that most of them are implicit. Chinese people are even unwilling to let others tell they are in positive emotions, not mentioned to those negative ones. And Interviewee 6 noted that in his daily life, he is not used to expressing his feelings online. Even once he used some "positive" emojis (i.e., the emojis showing positive emotions), the emojis did not mean that he really had positive emotions. As for the negative emojis (i.e., the emojis showing negative feelings), he said he just uses them a little bit more than the people who never use emojis. He adds that showing negative emotions to others, especially unfamiliar ones, is impolite. Hence, he seldom uses emojis that indicate negative emotions.

Moreover, from question 1 to question 3, it is evident that younger people have a more thorough and deep comprehension of emojis. That is to say. Younger people can feel the subtle difference between emojis. All the interviewees aged between 10-30 could tell the difference between the two emojis in questions 1 to 3, while not all the people from 31-50 years old could distinguish them. And I notice that younger people can quickly adopt the new meaning of emojis while older people stick with tradition. Like the first smiling face in question 3, two interviewees from 10-30 years old said it has the function of showing speechlessness and sarcasm. Young generation like to adopt some brand new meanings to emojis combined with the context, which also corresponds with the conversational implicature theory. The interpretation of people from 10-30 years old on emojis heavily relies on the context. Younger people can feel the implication of language. Interviewee 2 said, "In question 3, the first emoji shows negative emotion like speechless. However, whether this emoji expresses irony depends on the context."

In contrast, people in Chinese culture tend to express ironic intentions implicitly and indirectly through a smiling face ( ) that is explicitly polite and happy but implicitly sarcastic. [5] This opinion is the same as the opinion of interviewee 2 that this smiling face is a classic emoji that can show ironic intentions. More importantly, as interviewee 1 mentioned in question 1, he said, "Personally, there is usually a sense of irony in my expressions when chatting with emojis. The emojis enable us to convey more diverse emotions. Because one emoji can express various emotions depending on a different context." Hence, it is evident that people aged 10-30 are good at finding the implications of emojis compared to those aged 31-50. The quantitative analysis of Susan C. Herring also drew a similar conclusion. More respondents in the younger group reported that they were "very confident" that they understood the intended meaning of emojis when they saw them on social media (61%) as compared with older respondents (44%). Older respondents were more likely to report being "somewhat confident" (44%)—and, in some cases, "not at all confident" (12%)—than younger respondents (37%, 2%). [3]

) that is explicitly polite and happy but implicitly sarcastic. [5] This opinion is the same as the opinion of interviewee 2 that this smiling face is a classic emoji that can show ironic intentions. More importantly, as interviewee 1 mentioned in question 1, he said, "Personally, there is usually a sense of irony in my expressions when chatting with emojis. The emojis enable us to convey more diverse emotions. Because one emoji can express various emotions depending on a different context." Hence, it is evident that people aged 10-30 are good at finding the implications of emojis compared to those aged 31-50. The quantitative analysis of Susan C. Herring also drew a similar conclusion. More respondents in the younger group reported that they were "very confident" that they understood the intended meaning of emojis when they saw them on social media (61%) as compared with older respondents (44%). Older respondents were more likely to report being "somewhat confident" (44%)—and, in some cases, "not at all confident" (12%)—than younger respondents (37%, 2%). [3]

Based on the interview result, there is a distinguished difference between young people and older people in the preference for emojis. In the aspect of using frequency, it is evident that more senior people (i.e., the people aged 31-50) are not likely to use emojis that convey negative emotions. Based on the answer of interviewee 5. The reason for that is that most Chinese are conservative. They consider showing negative emotions impolite. In the aspect of feelings and attitudes toward emojis, young people (i.e., people aged 10-30 years old) have a deeper comprehension of emojis because they are more familiar with the Internet and its trend. Hence, they can combine emojis with the context and the trend. As interviewee 2 mentioned, "I think how I feel about one emoji is hard to define. It depends on the context. For example, this emoji, in the past, I just used to express awkwardness. But recently, the concept of "下头" has been popular, and many people link this emoji to emphasize the feelings that someone did something to ruin the atmosphere badly. So, once I use that emoji, the frustrating emotion is included." As a result, the older people sometimes feel puzzled about the young people's chat due to they do not understand the indication of emojis that is hidden in the context which is originated from the trend.

6. Acknowledgement

Throughout the writing of this dissertation, I have received a great deal of support and assistance.

I would first like to thank my supervisor, Yujing Su. From choosing the topic to writing my thesis, she gave me patience as well as careful guidance. Her suggestions and encouragement have given me much insight into these translation studies. When correcting my mistakes, at the same time, she also gives me encouragement and motivation. She has a wealth of theoretical knowledge that always leaves me in awe. When writing this paper, I realize that I have many problems, such as a lack of theoretical knowledge and practical experience, and I will take this as a warning to try to improve myself.

A special acknowledgement should be shown to Professor Andrew Nevins, whose lectures I benefited greatly and provided me with the tools I needed to choose the right direction and successfully complete my dissertation.

In addition, I would like to thank my parents. Because of them, I came into this colourful world. It is their hard work and meticulous care that enables me to grow up intact. They help me to solve many difficulties. They have stood by me and supported me unconditionally in the pursuit of my dreams. I'm very proud of them.

Finally, I could not have completed this dissertation without the support of my friend, Du Wen, who provided stimulating discussions as well as happy distractions to rest my mind outside of my research.

References

[1]. L. Li, Y. Yang, Pragmatic functions of emoji in internet-based communication---a corpus-based study, Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 2018, pp. 1-12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-018-0057-z.

[2]. T.K. Koch, P. Romero, C. Stachl, Age and gender in language, emoji, and emoticon usage in instant messages, Published by Elsevier Ltd., Computers in Human Behavior 126, 2022, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106990.

[3]. S.C. Herring and A.R. Dainas, Receiver Interpretations of Emojis Functions: A Gender Perspective, 2018

[4]. J.Cui, Respecting the Old and Loving the Young: Emoji-Based Sarcasm Interpretation Between Younger and Older Adults, Frontiers in Psychology 13:897153, 2022, DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.897153.

[5]. Zhou, B., and Gui, S. (2017). “WeChat and distant family intergenerational communication in China: A study of online content sharing on WeChat,” in New Media and Chinese Society. Communication, Culture and Change in Asia. Vol. 5. eds. 2017, DOI:10.1007/978-981-10-6710-5_11.

Cite this article

Zhao,J. (2023). Different Preferences for Emojis in the Aspect of Age. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,3,1142-1146.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2022), Part II

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. L. Li, Y. Yang, Pragmatic functions of emoji in internet-based communication---a corpus-based study, Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 2018, pp. 1-12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-018-0057-z.

[2]. T.K. Koch, P. Romero, C. Stachl, Age and gender in language, emoji, and emoticon usage in instant messages, Published by Elsevier Ltd., Computers in Human Behavior 126, 2022, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106990.

[3]. S.C. Herring and A.R. Dainas, Receiver Interpretations of Emojis Functions: A Gender Perspective, 2018

[4]. J.Cui, Respecting the Old and Loving the Young: Emoji-Based Sarcasm Interpretation Between Younger and Older Adults, Frontiers in Psychology 13:897153, 2022, DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.897153.

[5]. Zhou, B., and Gui, S. (2017). “WeChat and distant family intergenerational communication in China: A study of online content sharing on WeChat,” in New Media and Chinese Society. Communication, Culture and Change in Asia. Vol. 5. eds. 2017, DOI:10.1007/978-981-10-6710-5_11.

(cry)

(cry) (sob)

(sob) (awkward)

(awkward) (grinning face with sweat)

(grinning face with sweat) (smile)

(smile) (joyful)

(joyful)