1. Introduction

Equality in education is a fundamental principle that plays a crucial role in the development of a nation. In China, the government has made significant efforts to promote equality in education, recognizing that education is a key driver of economic growth and social progress [1].

Historically, education in China has been a privilege reserved for the elite, with access to education being largely determined by one’s social status and economic background. However, in recent decades, the Chinese government has made significant strides towards promoting equality in education. One of the most notable efforts has been the establishment of a nine-year compulsory education system, which requires all children to attend school for a minimum of nine years. This system has helped to increase access to education for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, as well as those living in rural areas [2].

To further promote equality in education, the Chinese government has also implemented a number of policies aimed at providing financial support to students in need. For instance, the government provides subsidies to families with children attending school and offers financial aid to students from low-income households. Additionally, the government has established a system of scholarships and grants to support students from disadvantaged backgrounds in pursuing higher education [1].

In recent years, the Chinese government has also invested heavily in improving the quality of education in rural areas, where access to education has traditionally been limited [3]. This has included the deployment of more trained teachers to rural schools and the establishment of boarding schools to provide children from remote areas with access to education.

Despite these efforts, however, challenges remain in achieving true equality in education in China. One of the most significant challenges is the urban-rural divide, which has resulted in uneven access to educational resources between urban and rural areas. While the Chinese government has made efforts to address this issue, such as by investing in rural schools, more needs to be done to ensure that all children, regardless of their geographic location, have access to quality education.

Another challenge is the persistence of inequality in education based on socio-economic status. While the government has implemented policies to support students from low-income households, the reality is that students from wealthier families often have greater access to educational resources, such as private tutors and extracurricular activities, which can give them an advantage in the highly competitive Chinese education system.

In conclusion, equality in education is a key priority for the Chinese government, and significant progress has been made in recent years. However, challenges remain in achieving true equality, particularly in addressing the urban-rural divide and socio-economic inequality. It is important for the government to continue to invest in education and to implement policies that ensure that all children have access to quality education, regardless of their background or geographic location. Only by doing so can China achieve its goal of becoming a truly equitable and prosperous society. In this paper, the author will explore the measures implemented in China to ensure equal access to education for all, as well as the challenges that remain in achieving true equality.

2. The Quest for Equality in Education in Ancient China

In ancient China, education was a significant means of social mobility, and the pursuit of equality in education was an essential aspect of Chinese society. However, the concept of equality in education varied depending on the dynasty and the social, economic, and political context of the time.

During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE), for example, the imperial government established a system of education that emphasized Confucianism and provided opportunities for individuals from all social classes to pursue education. This system was based on meritocracy, where individuals were selected for government positions based on their abilities, rather than their social status.

In the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), the government expanded the education system by establishing schools at the county level, which provided education to a broader range of students. Additionally, the government allowed more people to take the imperial exams, which were used to select individuals for government positions. While this did not necessarily guarantee equality in education, it did provide more opportunities for people from different social classes to pursue education and government positions.

During the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE), the government established private academies, which were run by scholars and provided education to students who could not afford to attend government schools. These academies emphasized Confucianism, but also included other subjects such as literature, history, and mathematics. This allowed more people to receive an education, regardless of their social status.

However, it is important to note that even with these efforts to pursue equality in education, there were still significant barriers to education for certain groups. For example, women were generally excluded from formal education, and individuals from lower social classes often lacked the resources and opportunities to pursue education.

Overall, the pursuit of equality in education in ancient China was an ongoing process, with varying degrees of success depending on the time period and the social and political context. Despite the challenges, education remained an important means of social mobility and a significant aspect of Chinese society.

3. An Analysis of Equality in Education after the Founding of China

3.1. 1949-1976

3.1.1. Education Policies

In the early years of the People’s Republic of China, from 1949 to 1976, the education policies were focused on the following things.

The policies expand basic education. The new Communist government aimed to increase literacy rates and provide universal primary education. There were major efforts to build more schools, increase enrollment rates, and make education more accessible especially in rural areas.

The education system reflected Communist and socialist values. The curriculum emphasized topics such as class struggle, Communist ideology, and political movements. Traditional Confucian teachings were banned.

There were also efforts to train more students in technical and scientific fields to support China’s industrialization. Many students were sent to study in universities and abroad.

By observing that before China’s reform and opening up, the main mode of education was based on the political system, as China needed to quickly stabilise the domestic situation and implement socialist rules and regulations, so all education was strongly political, and because China’s goal at that time was to develop into an industrially developed country, the government decided to send more young talents to study in the western developed countries, so education in China at that time was more focused on meeting the needs of national development.

3.1.2. Some Major Issues and Events in Education

Some major issues and events in education during this period include: The Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957, The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Lack of funding for education, Excessive politicization and Urban-rural divide.

Many intellectuals and educators were persecuted for expressing dissenting views. This hindered freedom of thought in academia. Schools were shut down for years and the education system was in disarray. Many educators and intellectuals were purged and persecuted. Although the government aimed to expand education, funding was limited. Schools and teachers lacked resources. Drop-out rates were high especially in rural areas due to poverty. The heavy focus on ideological education and political movements disrupted normal teaching and learning. Students spent more time on political activities than on actual studies. Educational opportunities and resources were far better in cities compared to the countryside. Rural students faced many difficulties in accessing education. This widened the gap between urban and rural areas.

So, in summary, while the new Communist government did expand basic education and trained more technical talent, the education system suffered from lack of funding, excessive politicization, and unequal access to education between urban and rural residents. The Anti-Rightist Campaign and Cultural Revolution caused major disruptions.

3.2. 1977-2000

3.2.1. Major Changes

After the Cultural Revolution, China launched the reform and opening up in 1978. This brought major changes to China’s education system.

China shifted from a highly centralized education system to one with more local control and diversified school types. This included the rise of private schools, vocational schools, and international schools. Education became more marketized, competitive, and privatized. Schools had more autonomy to charge tuition fees and compete for students and funds. Private education flourished. There was a surge in the number of universities, colleges, and students. China aimed to expand higher education to meet the needs of economic development. China sent more students abroad and also welcomed foreign students and universities. This increased international exchange and influence. The curriculum emphasized subjects like science, technology, English, and vocational skills - rather than political ideology. The goal was to cultivate more practical and globally-minded talent.

3.2.2. Major Challenges

Some major challenges during this period include inequality in access to education, declining quality, culture of cutthroat competition, over-reliance on exams and imbalance between disciplines.

Students from rural and poor areas faced disadvantages in gaining access to higher levels of education, especially college. This widened the gap between different social groups. As education expanded rapidly, the quality of many schools and universities declined due to lack of funding and qualified teachers. Diploma mills and fraud were common. The intense competition and obsession with scores and rankings created immense pressure and anxiety for students and parents. This led to issues like excessive cram schools and cheating. The education system focused too much on test scores and rankings rather than holistic development of students. This stifled creativity and motivation to learn. Chinese education prioritized science/technology fields over the humanities and social sciences. This resulted in talent that lacked breadth and depth.

So, in summary, China’s education policies since 1978 have led to greater access to education but also new challenges related to inequality, declining quality, overcompetition, and an imbalance between disciplines. Overall, China still needed improve the quality, equity, and purpose of its education.

3.3. 2000-2020

From 2000 to 2020, China’s education system continued to reform and face new challenges: balancing access and quality, promoting vocational education, improving rural education, tackling education inequality, reforming higher education, reducing over-competition, improving education equity and globalizing education.

China adopted policies to increase access to compulsory and higher education. But this has strained resources and worsened quality issues like large class sizes, outdated teaching methods, and lack of qualified teachers.

China expanded vocational schools and programs to train more technical and skilled talent. But vocational education still lacks prestige, and many students prefer the traditional path to college.

Policies aim to improve rural access to high school and college education through financial subsidies, preferential policies, and better school facilities. But the rural-urban gap remains large due to deeper issues like lack of family support and poverty.

China rolled out policies to improve education for migrant workers’ children, disabled students, and ethnic minorities. But inequality persists due to systemic barriers and lack of enforcement. There is still a long way to go to promote equitable and inclusive education.

Steps were taken to transform higher education through consolidating schools, improving quality and governance, encouraging international exchanges, and adopting innovative teaching models. However, these reforms are slow and higher education remains flawed.

New policies aim to reduce over-competition and over-reliance on exams like the Gaokao, such as piloting subjective admission criteria at some universities. But curbing excessive competition has proven challenging.

China has reformed hukou and provided more generous subsidies to address unequal access to education. However, hukou continue to limit rural migrants’ access to public education.

China promotes internationalization through Study Abroad programs, higher foreign student enrollment, and partnerships with foreign universities. However, education remains quite isolated due to political sensitivities and lack of English fluency.

In summary, China’s education reforms since 2000 have made progress in some areas but deeper issues like inequality, quality, over-competition, and access for disadvantaged groups persist. China still has a long way to go to build a world-class education system that is globally engaged, equitable, and innovative. Overall, balancing growth and quality improvement remains the key challenge.

3.4. 2020-2023

In modern China, the quest for equality in education has been a major priority of successive governments. Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the government has made significant efforts to increase access to education and to reduce disparities in educational outcomes between different regions and social groups.

One of the key strategies that the government has pursued is the expansion of the education system. This has involved building more schools, increasing the number of teachers, and providing more resources for education. Additionally, the government has implemented policies to promote access to education, such as the provision of free or subsidized education for children from poorer families and the establishment of vocational schools and adult education programs.

Another strategy that the government has pursued is the reform of the education system to make it more equitable. This has involved changes to the curriculum, such as the inclusion of subjects that are relevant to the needs of different regions and industries, as well as efforts to reduce the emphasis on standardized testing and rote learning. The government has also taken steps to reduce regional disparities in education by providing additional resources to underdeveloped regions and by encouraging teachers to work in these areas.

Before the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic, China had made significant progress in promoting equality in education. The government had implemented various policies aimed at reducing the urban-rural divide and socio-economic inequality in education.

One of the key initiatives was the implementation of the Nine-Year Compulsory Education system, which required all children to attend school for at least nine years. This system significantly improved access to education for children from rural areas and disadvantaged backgrounds. The government also invested heavily in improving the quality of education in rural areas, providing subsidies to families with children attending school, and offering financial aid to students from low-income households.

The Chinese government had implemented policies aimed at providing equal opportunities for students from different regions to access higher education. For instance, the government had established a system of scholarships and grants to support students from disadvantaged backgrounds in pursuing higher education. The government also encouraged universities to give preferential treatment to students from rural areas and ethnic minority groups during the admission process [1].

Moreover, the government had been investing in the development of vocational education, providing opportunities for students who were not academically inclined to gain practical skills and knowledge. The government had also been promoting equal access to higher education for students with disabilities, providing special education programs and facilities.

Despite these efforts, however, challenges remained in achieving true equality in education. The urban-rural divide remained a significant issue, with students from urban areas having greater access to educational resources and better-funded schools than those from rural areas. Socio-economic inequality also continued to affect educational opportunities, with students from wealthier families having greater access to private tutoring and extracurricular activities.

Table 1: Basic education in China 1949-1990. [4]

Primary | Junior High | Academic Senior High | |||||||

Year | Urban | Rural | Rural % | Urban | Rural | Rural % | Urban | Rural | Rural % |

1962 | 526,000 | 1,985,000 | 79.05 | 197,618 | 120,743 | 37.93 | 74,877 | 6,218 | 7.67 |

1963 | 569,000 | 2,032,000 | 78.12 | 220,153 | 120,181 | 35.31 | 74,574 | 5,557 | 6.93 |

1964 | 596,000 | 2,512,000 | 80,82 | 231,456 | 131,200 | 36.18 | 71,841 | 7.018 | 8.90 |

1965 | 674,000 | 3,183,000 | 82.53 | 248,001 | 131,164 | 34.59 | 70,910 | 7,000 | 8.98 |

1971 | 594,000 | 3,501,000 | 85.49 | 306,786 | 727,736 | 70.35 | 100,408 | 191,632 | 65.62 |

1972 | 654,000 | 3,744,000 | 85.13 | 337,805 | 926,636 | 73.28 | 174,502 | 213,671 | 55.62 |

1973 | 684,000 | 3,995,000 | 85.38 | 362,660 | 911,031 | 71.53 | 207,427 | 214,816 | 50.87 |

1974 | 693,000 | 4,251,000 | 85.98 | 372,327 | 952,053 | 71.89 | 233,783 | 223,830 | 48.91 |

1975 | 690,000 | 4,514,000 | 86.74 | 399,884 | 1,161,826 | 74.39 | 250,323 | 280,122 | 52.81 |

1976 | 672,000 | 4,617,000 | 87.29 | 453,488 | 1,581,148 | 77.71 | 257,903 | 436,440 | 62.86 |

1977 | 660,000 | 4,566,000 | 87.37 | 491,462 | 1,869,647 | 79.19 | 282,216 | 543,367 | 65.82 |

1978 | 691,000 | 4,535,000 | 86.78 | 518,909 | 1.921,791 | 78.74 | 303,570 | 437,729 | 59.05 |

1979 | 729,000 | 4,653,000 | 85.45 | 529,853 | 1,880,395 | 78.02 | 332,731 | 334,717 | 50.15 |

1980 | 773,000 | 4,726,000 | 85.94 | 574,400 | 1,874,623 | 76.55 | 322,378 | 248,349 | 43.51 |

1981 | 816,000 | 4,764,000 | 85.38 | 622,364 | 1,727,153 | 73.71 | 302,875 | 191,565 | 38.74 |

1982 | 854,000 | 4,651,000 | 84.49 | 664,111 | 1,550,631 | 70.01 | 300,388 | 165,429 | 35.51 |

1983 | 863,000 | 4,562,000 | 84.09 | 672,576 | 1,473,213 | 68.66 | 305,977 | 145,134 | 31.17 |

1984 | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . |

1985 | 1,084,000 | 4,293,000 | 79.84 | 765,272 | 1,394,633 | 64.57 | 369.011 | 122,679 | 24.95 |

1986 | 1,087,000 | 4,327,000 | 79.92 | 790,109 | 1,449,209 | 64.72 | 398,028 | 120,311 | 23.21 |

1987 | 1,153,000 | 4,281,000 | 78.78 | 823,494 | 1,503,033 | 64.60 | 410,988 | 132,909 | 24.44 |

1988 | 1,229,000 | 4,272,000 | 77.66 | 873,076 | 1,529,666 | 63.66 | 420,619 | 136,267 | 24.47 |

1989 | 1,304,000 | 4,240,000 | 76.48 | 902,875 | 1,523,705 | 62.79 | 420,731 | 133,126 | 24.04 |

1990 | 1,319,000 | 4,263,000 | 76.37 | 920,673 | 1,549,682 | 62.73 | 429,324 | 132,942 | 23.64 |

Table 1 shows that during the Cultural Revolution, the largest number of teachers went to rural or remote areas to support rural education, and after the Cultural Revolution the number of teachers working in rural areas dropped rapidly.

Cross-cohort changes in educational attainment calculated from 1990 census data confirm the trends shown in the ratios in the preceding section. “ Dissimilar to the progress proportions recently examined, these figures truly do address the genuine verifiable instructive experience of the 1990 populace. However, due to the potential issue of rural-to-urban migration, cross-cohort changes must be interpreted with caution. Throughout the People’s Republic of China’s history, migration has been tightly controlled but not completely stopped. The population’s differences in educational attainment between urban and rural areas are mixed effects of the rural-to-urban migration: Migrants are a mix of the “floating population,” or students who leave rural areas to find work, and the “most educated sub population,” or students who leave rural areas to attend college.

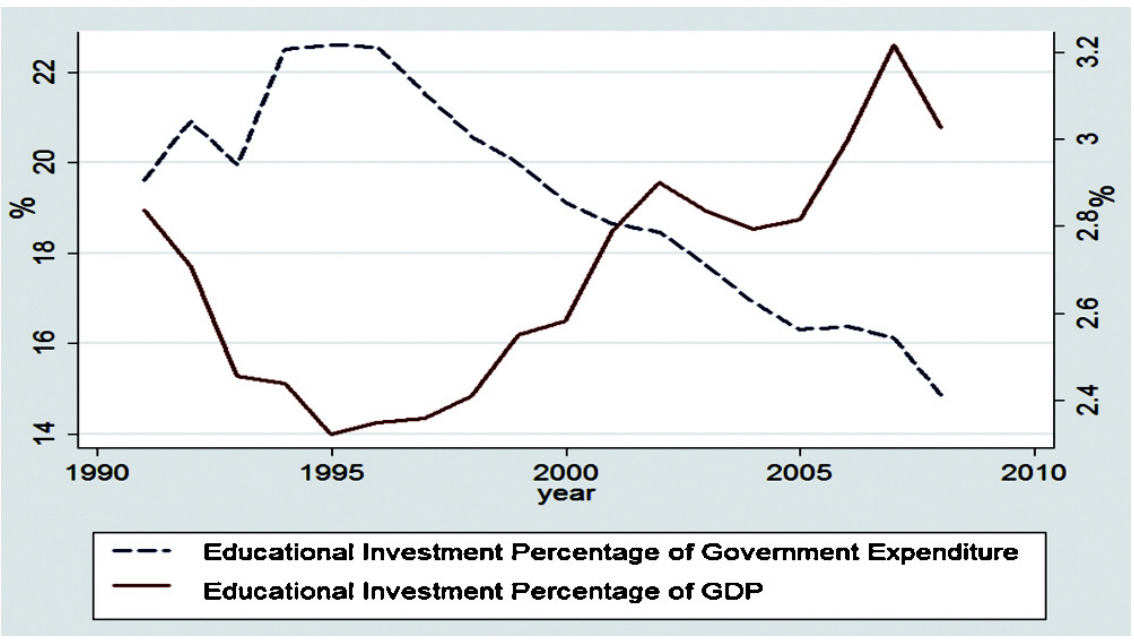

The government’s goals are crucial to education policy and distribution because the majority of educational resources are under its control. Regardless of the way that schooling improvement is seen as a fundamental state strategy in China, the proportion of public consumption on training doesn’t stay up with the Gross domestic product development rate. According to the graph, the percentage of government spending on education remains low (less than 3 percent in most years). In 2008, they spent 6.1% of their GDP on educational institutions, whereas only nine of the 36 countries for which data are available spent less than 5% of GDP; It also reveals that only a small portion of China’s national finance revenue is allocated to education, and that spending on all levels of education increased faster than GDP between 2000 and 2008.3 In point of fact, insufficient investment in education always results in educational inequality and unbalanced development.

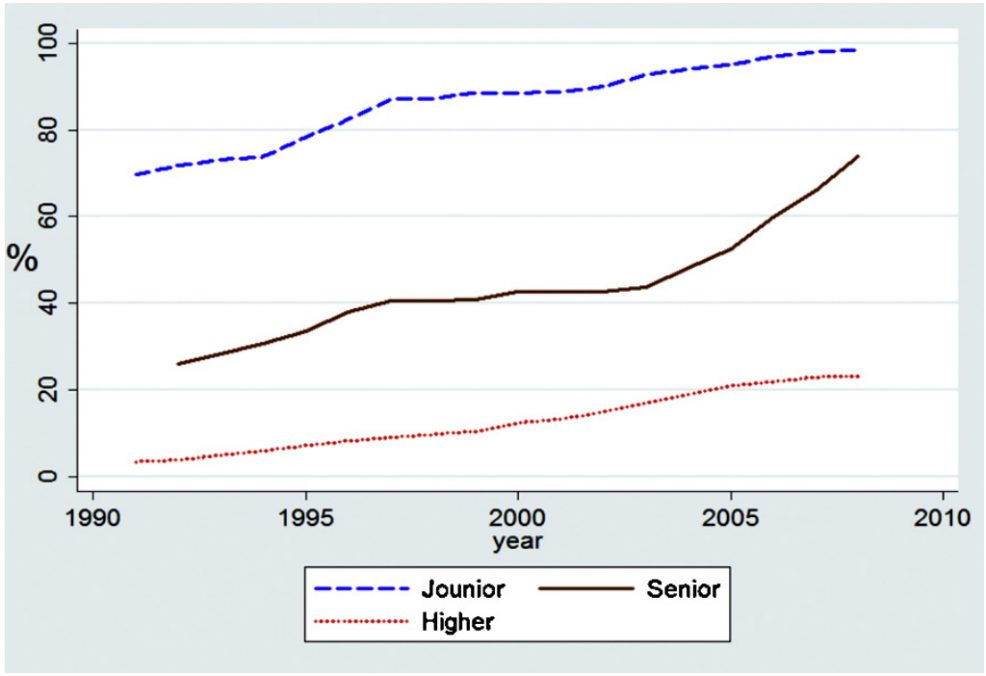

Figure 1: Chinese education enrollment rate by years [5,6].

Note: Senior School includes regular secondary schools and vocational.

Figure 2: China’s educational investment percentage of government expenditure (GE) and GDP [7-9].

The educational gap has narrowed considerably in recent decades through the promotion of gender equality and the introduction of compulsory education. However, gender inequality in rural education is still significantly exacerbated by poverty. Men get more education than women do in China’s poor rural areas because there aren’t enough diversified household livelihood capitals. In a nutshell, despite the significant reduction in the educational gap between men and women, these disparities persist and require additional investigation.

In addition, the age factor can also lead to educational inequality. The reason may be that older people tend to be less educated than younger people. In recent decades, the policy of expanding education has improved the educational attainment of young people, especially the nine-year compulsory education has ensured that most urban and rural children can receive basic education. In addition, gender differences are not an important factor in causing general educational inequality. Women enjoy equal educational opportunities to a large extent, so that every female student can receive basic education. While there is still a gap in educational attainment between men and women, this is partly due to the educational system and other reasons such as culture, customs and family values.

In conclusion, before the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic, China had made significant progress in promoting equality in education. The government had implemented various policies aimed at reducing the urban-rural divide and socio-economic inequality in education. However, challenges remained in achieving true equality in education, particularly in addressing the urban-rural divide and socio-economic inequality. The COVID-19 epidemic has further highlighted these issues, with the pandemic exacerbating existing inequalities in education.

4. On the Education of Left-behind Children in China

The education of left-behind children in China is a significant issue that has received attention from the Chinese government and international organizations in recent years. Left-behind children are those who are left behind in rural areas while their parents migrate to urban areas for work, which can result in difficulties in accessing education and other essential services.

The Chinese government has implemented several policies and initiatives to address the education needs of left-behind children. One of the key initiatives is the “Two Basics” policy, which aims to ensure that all children have access to nine years of compulsory education and basic healthcare. The government has also launched programs to provide financial assistance to left-behind children, such as subsidies for tuition, textbooks, and living expenses.

In addition, the government has invested in building more schools and improving the infrastructure of existing ones in rural areas, with a particular focus on areas with high numbers of left-behind children. The government has also introduced measures to improve the quality of education in rural areas, such as training programs for teachers and the development of new teaching materials.

Furthermore, the government has encouraged urban schools to partner with rural schools to share resources and expertise, which can help to improve the education of left-behind children. The government has also launched campaigns to encourage more parents to bring their children with them when they migrate to urban areas, or to return to their home regions to care for their children.

Despite these efforts, however, the education of left-behind children in China remains a significant challenge. One issue is the shortage of qualified teachers in rural areas, which can result in lower quality education for left-behind children. Additionally, there are concerns about the impact of social and emotional isolation on left-behind children, as well as the lack of access to extracurricular activities and support services.

Regardless of the difficulties, a rising number of transients have started carrying their youngsters to the urban areas [5]. These are the so-called migrant children of China. Left-behind children are people whose parents stay in the countryside while moving to the city for work. According to ACWF (2008), the number of migrant children has been rising rapidly. In China’s cities in 2008, an estimated 20 million migrant children were living with their parents. The education of migrant children has become one of the greatest challenges for both migrant families and the Chinese education system as the number of children from migrant families has increased. This challenge has not always been met successfully. In China today state funded schools in both provincial and metropolitan regions should give free training to kids. Be that as it may, this free training is just ensured for youngsters whose hukou matches the school’s area. Because migrant children in cities still have their rural hukous, they can only attend urban public schools if there is room. Migrant parents often cannot enroll their children in urban public schools unless they are willing and able to pay high tuition fees outside of their district. Thus, in significant metropolitan regions, for example, Beijing, a huge number of kids are as yet unfit to go to state funded schools, falling into an obvious hole in the arrangement of government funded training [5].

Privately run, Due to the inability of the public education system to accept migrant children, fee-paying, for-profit migrant schools emerged in the 1990s. These schools quickly became the main places of education for children of migrant workers. Migrant workers’ children, regardless of their hukou status, can enroll in migrant workers’ schools at a lower tuition fee than public schools charge non-local students. As a result, many parents turn to migrant schools when they cannot get their children into urban public schools. Estimates are high, although data are lacking on the exact percentage of migrant children attending migrant schools. For example, an estimated 70 percent of migrant children attend migrant schools in Beijing. According to Stepping Stones’ case study on the education of migrant children in major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, hundreds of thousands of migrant children attend migrant schools [6].

Overall, the education of left-behind children in China continues to be an important issue, and while the government has implemented various policies and initiatives to address this issue, there is still much work to be done to ensure that all children in China have access to high-quality education and equal opportunities.

5. Exploring Equity in Chinese Education in the Face of an Epidemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly impacted education systems around the world, forcing schools to close and rely on remote learning. In China, the pandemic has exposed existing gaps in educational equity, particularly for students from rural and low-income areas. This article will discuss the challenges faced by Chinese education during an epidemic and analyze the strategies being implemented to create a more equitable system.

First, focusing on challenges to Educational Equity, (I) “Digital Divide”: With the shift to online learning, students without access to technology or stable internet connections are at a significant disadvantage. This digital divide particularly affects students in rural areas, where internet infrastructure is less developed. (II) “Limited Resources”: Schools in rural and low-income areas often have fewer resources, such as well-trained teachers and modern educational facilities, compared to their urban counterparts. These limitations can hinder the quality of education received by students in these regions. (III) “Curriculum Differences”: The Chinese education system is characterized by regional disparities in curriculum and teaching methods. This can lead to students in rural areas receiving an education that may not be as comprehensive or up-to-date as that of their urban peers. (IV) “High-stakes Testing”: The Chinese education system places a strong emphasis on high-stakes examinations, such as the gaokao (college entrance examination). Students from rural areas may face additional challenges in preparing for these exams due to limited resources and support [4].

The Ministry of Education launched an emergency policy initiative titled “Suspending Classes Without Stopping Learning” to switch teaching to large-scale online instruction while schools were closed. The emergency policy known as “Suspending Classes Without Stopping Learning” did not go through the normal policy-making process, so its meaning, conditions of implementation, process of implementation, and effects are still a mystery. The benefits and drawbacks of the policy’s implementation merit careful consideration and investigation [3].

The benefits of the state’s policy of stopping classes without stopping school are numerous, such as the fact that the same educational resources are available everywhere, as a large number of learning resources and different learning platforms can be found by simply searching on the internet, but a closer analysis reveals that there are many disadvantages to this method of online teaching.

So the Chinese government has found itself in the process of implementing such policies and needs to make real changes in order to achieve the goal of equity in education,so Chinese government focus on the Strategies to Promote Equity: (1). “Improving Access to Technology”: The Chinese government has taken steps to bridge the digital divide by providing subsidies for internet access and distributing devices to students in need. Additionally, efforts have been made to improve internet infrastructure in rural areas. (2). “Targeted Funding”: To address the resource gap in rural and low-income schools, the government has implemented targeted funding programs. This funding is directed towards improving facilities, providing teacher training, and offering additional support for students in need. (3). “Curriculum Reform”: In an effort to standardize education across the country, China has introduced a new national curriculum. This aims to reduce regional disparities in teaching methods and content, ensuring that all students receive a comprehensive education. (4). “Alternative Pathways to Success”: To reduce the pressure of high-stakes testing, alternative pathways to higher education and vocational training have been promoted. This allows students from rural areas to access opportunities without solely relying on high-stakes examinations. (5). “Community Involvement and Support”: Grassroots organizations, NGOs, and local communities have also played a crucial role in supporting education during the pandemic. They have provided additional resources, tutoring, and emotional support for students in need [3,10].

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for greater equity in Chinese education. While significant challenges remain, the government and local communities have taken steps to address these disparities through targeted funding, improved access to technology, and curriculum reform. Continued efforts to promote equity will be essential in ensuring that all students in China have the opportunity to succeed in the face of epidemics and beyond.

6. The Chinese Government’s Efforts for Equality in Education in China

The Chinese government has implemented various efforts to promote equality in education across the country. One of the key initiatives is the “compulsory education” policy, which requires all children to receive at least nine years of education, regardless of their family’s financial situation or location.

The government has launched programs to provide financial assistance to students from low-income families and rural areas, including subsidies for tuition, textbooks, and living expenses. The government has also established a system of scholarships and grants to support disadvantaged students, including those from ethnic minority groups.

To address the urban-rural education gap, the government has invested in building more schools and improving the infrastructure of existing ones in rural areas. The government has also introduced measures to improve the quality of education in rural areas, such as training programs for teachers and the development of new teaching materials.

The Chinese government has placed a strong emphasis on vocational education, aiming to provide students with practical skills and prepare them for the workforce. The government has established vocational schools and training centers and has also implemented policies to encourage businesses to hire graduates of these programs.

In recent years, the Chinese government has implemented several reforms to improve the quality of education across the country. One of the key initiatives has been the “New Curriculum Reform,” which aims to shift the focus of education from rote memorization to critical thinking, creativity, and practical skills. The reform includes changes in teaching methods, curriculum content, and assessment methods.

The government has also introduced measures to address the issue of unequal distribution of resources between urban and rural areas. For example, the government has provided extra funding to schools in rural areas and has encouraged urban schools to partner with rural schools to share resources and expertise.

Another important aspect of the Chinese government’s efforts for equality in education is the promotion of education for girls and women. The government has launched campaigns to encourage more girls to attend school and has provided financial assistance to families who cannot afford to send their daughters to school. In addition, the government has introduced policies to promote gender equality in education, such as the requirement for equal access to education and job opportunities for men and women.

However, despite these efforts, challenges remain in achieving true equality in education in China. One of the biggest challenges is the issue of inequality between urban and rural areas, as well as between different regions within the country. There are also concerns about the quality of education in some areas, particularly in rural areas, where there is a shortage of qualified teachers and educational resources.

7. Conclusions

China’s education system has undergone significant changes over the past few decades. Historically, China has placed a strong emphasis on education, and this emphasis has only grown stronger in recent years. Today, China has one of the largest education systems in the world, with over 200 million students enrolled in schools.

One of the most notable changes in China’s education system has been the rapid expansion of higher education. In the past, only a small percentage of Chinese students were able to attend college or university, but today, millions of students are enrolled in higher education programs. This has been made possible by the government’s investment in education, as well as by the expansion of private universities.

Another key change in China’s education system has been the shift towards a more student-centered approach to learning. Traditionally, education in China has been very teacher-centered, with students expected to memorize information and follow strict rules. However, in recent years, there has been a push to make education more creative, interactive, and focused on problem-solving. This has been reflected in the adoption of new teaching methods, such as project-based learning and collaborative learning.

The government has also been working to address issues of inequality in the education system. In the past, students from rural areas and low-income families have had limited access to quality education, but the government has implemented policies designed to address this. For example, the “Two Basics” policy aims to provide universal access to nine years of compulsory education and to eliminate illiteracy among young and middle-aged adults.

However, there are still challenges facing China’s education system. One of the biggest issues is the intense competition for admission to top schools and universities, which has led to high levels of stress among students and their families. Additionally, there are concerns about the quality of education in some areas, particularly in rural areas where resources can be limited.

Overall, China’s education system is undergoing significant changes, with a focus on expanding access to education, promoting innovation in teaching and learning, and addressing issues of inequality. While there are still challenges to be addressed, these changes are helping to shape the future of education in China.

References

[1]. Emily Hannum, (2015) Political Change and the Urban-Rural Gap in Basic Education in China, 1949-1990,29-203.

[2]. Ministry of Education, (1985) Department of Planning, ed., Achievement of Education in China: Statistics, 1949-1983. Beijing: People’s Education Press, pp. 200, 222.

[3]. Wunong Zhang, Yuxin Wang, Lili Yang and Chuanyi Wang. (2020) Suspending Classes Without Stopping Learning:China’s Education Emergency Management Policy in the COVID-19 Outbreak, P2-P6.

[4]. Fang, Xu. (2018) Empirical Analysis of Affirmation of National Boutique Online Open Courses. China Higher Education Research 7: 94–99. (In Chinese).

[5]. Han, Kwong, (2004) The education of China’s migrant children: The missing link in China’s education system.

[6]. Fang Lai, Chengfang LIu, Renfu Luo, Linxiu Zhang, Xiaochen Ma,Yujie Bai, Brian Sharbono, Scott Rozelle. (2004) The education of China’s migrant children: The missing link in China’s education system.

[7]. CCTV News. (2020) Ministry of Education: Guarantees University’s Online Teaching During Epidemic Prevention and Control Period. Available online: http://news.cctv.com/2020/02/05/ ARTI0WhqsINuV5dCRBUnbXod200205.shtml (accessed on 3 March 2020).

[8]. CCTV News. (2020) How to Help the Poor Students Get the Online Courses. Available online: https://toutiao.china.com/shsy/gundong4/13000238/20200304/37868320_2.html (accessed on 4 March 2020).

[9]. McAleer, Michael. (2020) Prevention Is Better Than the Cure: Risk Management of COVID-19. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13: 46.

[10]. Guo, Xiang, Lian Tong, and Linxia Tang. (2008) A Literature Review of the Emergency Management Policy Overseas. Soft Science 22: 34–36. (In Chinese).

Cite this article

Zhou,J. (2023). Educational Equity in China's Education System under Different Perspectives. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,18,279-290.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Emily Hannum, (2015) Political Change and the Urban-Rural Gap in Basic Education in China, 1949-1990,29-203.

[2]. Ministry of Education, (1985) Department of Planning, ed., Achievement of Education in China: Statistics, 1949-1983. Beijing: People’s Education Press, pp. 200, 222.

[3]. Wunong Zhang, Yuxin Wang, Lili Yang and Chuanyi Wang. (2020) Suspending Classes Without Stopping Learning:China’s Education Emergency Management Policy in the COVID-19 Outbreak, P2-P6.

[4]. Fang, Xu. (2018) Empirical Analysis of Affirmation of National Boutique Online Open Courses. China Higher Education Research 7: 94–99. (In Chinese).

[5]. Han, Kwong, (2004) The education of China’s migrant children: The missing link in China’s education system.

[6]. Fang Lai, Chengfang LIu, Renfu Luo, Linxiu Zhang, Xiaochen Ma,Yujie Bai, Brian Sharbono, Scott Rozelle. (2004) The education of China’s migrant children: The missing link in China’s education system.

[7]. CCTV News. (2020) Ministry of Education: Guarantees University’s Online Teaching During Epidemic Prevention and Control Period. Available online: http://news.cctv.com/2020/02/05/ ARTI0WhqsINuV5dCRBUnbXod200205.shtml (accessed on 3 March 2020).

[8]. CCTV News. (2020) How to Help the Poor Students Get the Online Courses. Available online: https://toutiao.china.com/shsy/gundong4/13000238/20200304/37868320_2.html (accessed on 4 March 2020).

[9]. McAleer, Michael. (2020) Prevention Is Better Than the Cure: Risk Management of COVID-19. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13: 46.

[10]. Guo, Xiang, Lian Tong, and Linxia Tang. (2008) A Literature Review of the Emergency Management Policy Overseas. Soft Science 22: 34–36. (In Chinese).