1. Introduction

The study of the relationship between linguistics and psychology can be tracked back to 20th century when these two disciplines developed as scientific fields. However, at the beginning, linguists like Ferdinand de Saussure and Leonard Bloomfield focused primarily on the formal analysis of language structure. Then in the mid-20th century, psycholinguistics emerged later and understood how languages were processed and represented in mind. In the 1950s and 1960s, the relationship between the two majors became much solidified with the study of cognitive psychologists, such as Jean Piaget and Jerome Bruner. Since then, linguistics and psychology have continued to grow stronger. Linguistics provides a framework for understanding the structure and properties of language, while psychology contributes insights into how language is processed, acquired, and used by individuals.

2. The Definition of Linguistic Change

Linguistic change refers to the process of languages evolving and transforming over time. It is associated with the alternations of pronunciations, vocabulary, structure and usage of languages and have affects on phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics and so on. It is a natural process occurs in all kinds of languages.

Languages become meaningful because of the existence of human who create and use it. It is certain that people’s mental factors influence the contents of languages.

2.1. The Influence of Psychological Factors on Sound Change

Briefly, the influence of psychology on sound change is complex and multi-faceted. And obviously, psychology is not the only factor that contributes to sound change [1]. It has many interactions with other elements, such as speech rates, articulatory constraints and language experience. However, this part will focus on the social psychology layer.

Language serves as a tool for people to convey their mind and communicate with each other, and it is a social bond constructed by human interaction [2]. Because people must be involved in this process, psychology plays an important role in driving language variation and change. Social psychology factors such as identity, social status and linguistic prestige can influence how individuals perceive and adapt to new sounds or pronunciation patterns. This can lead to sound changes over a community and even spreading to a whole country.

2.1.1. Social Identity

Firstly, in terms of social identity, it includes age, gender, ethnicity, which focuses more on being a membership of specific social group [3]. According to social identity theory, proposed by Henri Tajfel and John Turner in 1979, suggests that individuals strive to maintain a positive social identity by identifying with certain social groups [4]. Social identity is tied closed with a sense of belonging which human need to feel connected, accepted, and valued within social groups or communities. In this way, people may adopt certain speech pattern or accents to align themselves with a particular social group, gradually resulting in sound change.

2.1.2. Social Status

Secondly, when it comes to social status, it relates more to the position or rank of individuals in social hierarchy based on wealth, education or occupation [5]. Then, individuals with higher social status may have more influence on language change. They are considered to access better education, social networks and increased exposure to standard languages and prestigious dialects. As a result, their speech patterns and pronunciations may be seen as more reliable and influential. What is more, the higher status person has, the more possibility to become well-known he or she has. And when a famous person speaks on social media, like TV show or movies, his or her accent can be spread rapidly and thus has more possibility to be accepted and imitated. Meanwhile, those from lower status backgrounds may strive to upward mobility. They may conscious or unconsciously adopt the speech sounds that are perceived as appropriate in higher status, while avoid the sounds that are inappropriate or even deviant.

2.1.3. Linguistic Prestige

Thirdly, regarding the linguistic prestige, it usually means some linguistic features or varieties are seen as more valued or popular within a certain society or community [6]. It often involves associating higher status with certain ways of speaking and viewing them as more educated, formal, or socially desirable. Its affect can be similar to that of individual’s social status, and it just like the social status of a sound.

Then, there is a typical example that can serve as a proof of the arguments above: the history of [r] sound in English and American. Social psychology factors impeded the nature process of sound change in these two countries, and the opposite situation of social status, linguistic prestige and social identity can lead to an opposite direction for [r] sound change.

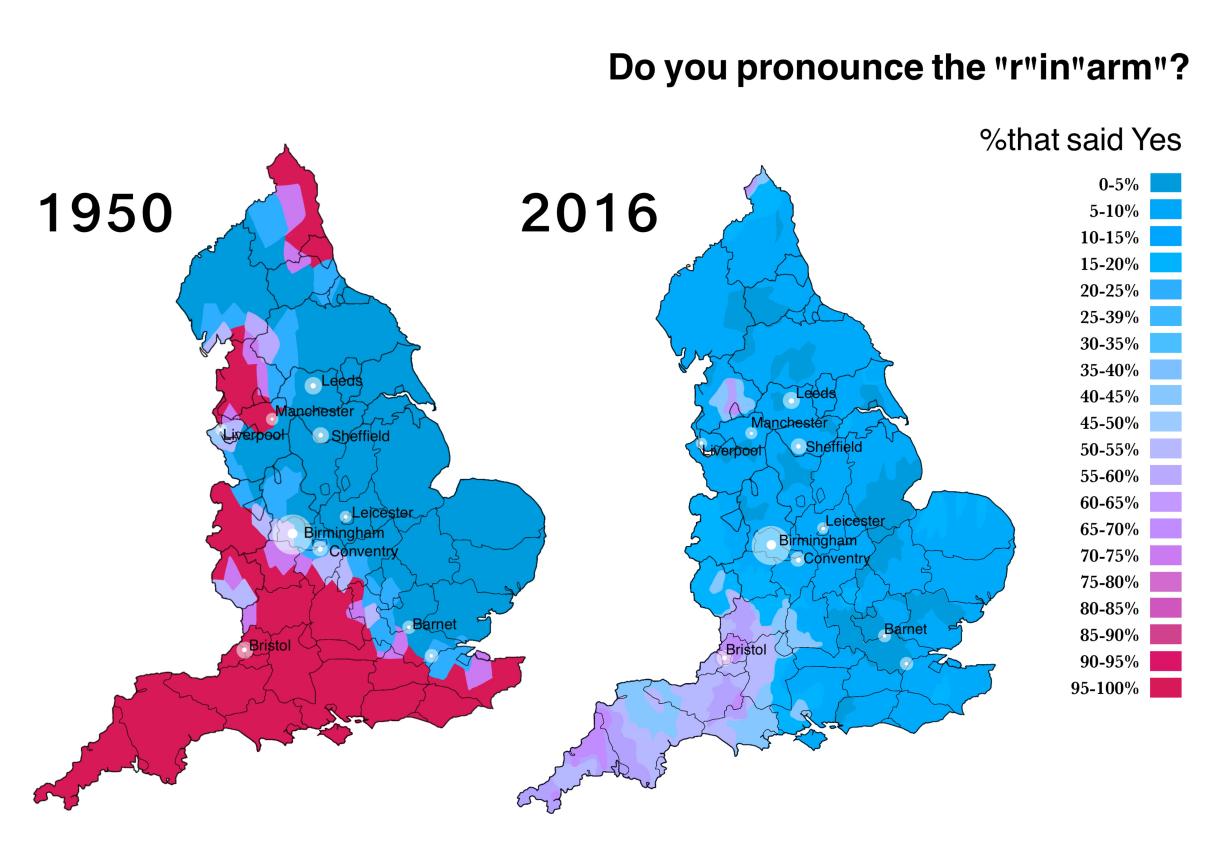

Figure 1: The change fortune of [r] sound in British from 1950 to 2016. (photo credit: original)

As shown in Figure 1 in 1950, roughly half of resigns consist of a few area in the north British and most in the southwest in English are rhotic, while people who are non-rhotic mainly in the Thames estuary, around London. However, in 2016, the majority of population are non-rhotic leaving rhotic accent which are restricted to the southwest and parts of the northwest. This phenomenon is significantly caused by social psychology factor:

From the social status to see, Non-rhotic English was associated with people who came from certain upper-class and had educated accents in Britain around the 1950s [7]. This pronunciation may spoken by British aristocracy with refined culture. Also, Individuals who attended prestigious schools, especially those affiliated with Oxbridge (Oxford and Cambridge), often acquired non-rhotic accents as part of their education. This contributed to the perception that those with non-rhotic accents were well-educated and came from privileged backgrounds.

From the linguistic prestige, non-rhotic accent was generally recognized as standard English. For example, people would hear non-rhotic pronunciation, if they opened broadcasters around 1950, including BBC, which were highly respected and influential. The similar things would happen in the theatre, or film. Hearing non-rhotic accents on the social medias like in news broadcasts contributed to their association with authority and professionalism.

Eventually, social identity became a important factor for sound shift. More and more people intend to choose non-rhotic pronunciations, because this accent became markers of social status and distinction in some extent. In this way, it serves as a way of improving their social standing. As a result, non-rhotic accents occupies a dominant position until now.

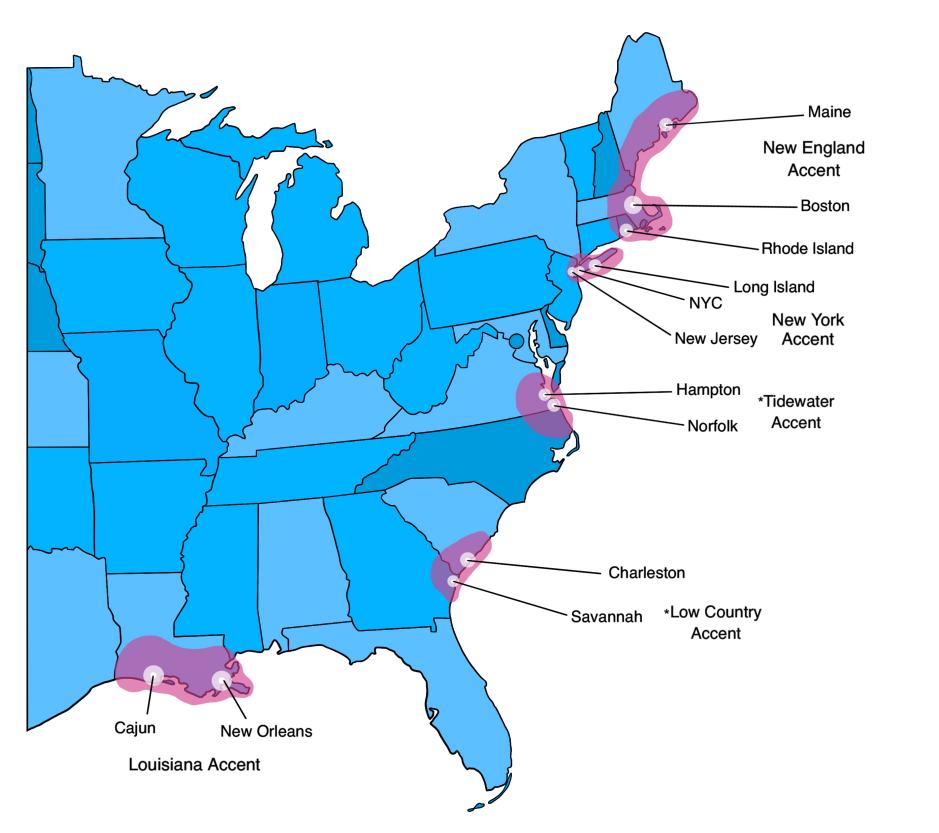

However, what is quite different is that American evidences an opposite trend, because the prestige of rhotic pronunciation has increased since 1940s. In the past, non-rhotic accents allocated around southeastern England, while rhotic accents in the western England, Scotland, north of Ireland (‘Scotch-Irish’). But now, non-rhotic accents historically restricted to north east and parts of the South, whereas rhotic accents are elsewhere in the US, even in Canada.

Figure 2: The resigns using non-rhotic accents in American. (photo credit: original)

For the same speech sound, there are different changing fortunes in these two countries due to opposite social status and linguistic prestige. It shows the significant influence of social psychology factors.

2.2. The Influence of Psychological Factors on Word Change

Psychology plays an important role in the word change in linguistics, like social cultural and norm, pragmatic adaptation and cognitive efficiency [8]. Before analyzing the affect of psychology, it is better to introduce an English “bleaching” phenomenon of word semantic change: Bleaching refers to a process by which a word loses its part or all of its original meaning and gradually has another concept. The word “nice” is an example that has gone through significant semantic change over the centuries.

The meaning of “nice” word has changed for a long period, and it occurred among English-speaking community worldwide. Therefore, it is difficult to figure out the pinpoint time when it started to evolve and ended. Besides, it is not limited to a particular place or resign. However, its original connotation can be traced back to Middle English, where its origins in the Latin term “nescius,” means “ignorant” or “foolish.” Over time, its concept evolved to include “careful,” “precise” and “delicate.” By the 18th century, “nice” started to acquire positive meaning and was connected with being an agreeable and pleasant. This semantic shift likely occurred gradually under the influence of several psychological factors.

2.2.1. The Way of Memory: A Premise of Semantic Change

The way that human memory words provides a possibility for a same-sound word to evolve from one meaning to another meaning [9]. According to the knowledge of human mental grammar, the mental lexicon stores all of the words known to individuals. But it is significant that the information for phonological form and semantic content are stored respectively by people, which means it is possible for a word or phrase to have multiple distinct meanings or semantic contents. In such cases, the phonological form remains the same, but the semantic interpretation changes based on context or usage. Therefore, a same-sound word can gradually include more than one kind of meaning, like “nice” may have the meaning “ignorant,” as well as the meaning “careful” in a period. Totally, this can be a premise of word semantic change.

2.2.2. Social Culture and Norm: A Factor Why Other Meaning Occurred

The words are used by human, so the habit and preference of a group of people may be essential for the meaning shift of words [10]. Hence, the social culture and norm may serve as a catalyst for the appearance of the positive meaning for “nice” word. In many cultures, politeness and positive social interactions are highly valued and then become a recognized manners or norms among the whole society. Then, the “foolish” meaning of “nice” was used less and less for avoiding being offend or rude, whereas the relative pleasant concepts became more and more prevalent. In this way, “Nice” was often used as a socially acceptable and non-committal way to express approval without delving into specific details or providing deeper insights. Ultimately, because of its frequent and widespread use in everyday language, the positive meaning of “nice” became a independent element in people’s mental grammar.

2.2.3. Cognitive Efficiency: How the Original Meaning Was Forgotten

Cognitive efficiency refers to the ease and efficiency with which human’s cognitive processes operate [11]. People’s brains are wired to maximize efficiency and minimize cognitive load. In terms of language, individuals naturally prioritize information that is more essential for communication. When a word or morpheme is used repeatedly in a specific context, human’s brains tend to generalize its meaning or function to save cognitive resources. This is associated with how a new meaning of a word is stored in brain. However, when a word meaning becomes less necessary or is used less and less frequently, it may gradually fade from collective memory. In the case of “nice,” its original meaning of “foolish” or “precise” may have became less relevant among the society over centuries. And naturally they were abandoned by our cognitive efficiency strategy. After generation and generation, these concepts lost by people withdraw from the stage of history. As a result, the “nice” is basically solely means agreeable or pleasant nowadays.

Overall, there lies significant influence of psychological factors in the meaning change of “nice” word. Additionally, beside “nice”, there are numerous words have experienced some degrees of bleaching throughout history, such as “cool,” “awesome,” and “silly”. That proofs this phenomenon is universal and hence the affect of psychology on word change is widespread as well.

2.3. The Influence of Psychology on Syntactic Change

This part will introduce the influence of psychological factors on syntactic change. Syntactic change refers to the evolution of structure of a language’s syntax over time. And it is closely intertwined with psychological aspects of human and human society. In terms of human, people create language to communicate with each other efficiently to survive better. Consequently, the structure and organization of language, including syntax, must be reasonable for our cognitive style. And as for human society, the group consciousness will play a vital role to affect or even decide and then change the use of language.

2.3.1. Cognitive Efficiency

First of all, cognitive efficiency serves as a radical cause for syntactic change, because it is closely related how much energy that people need to survive [12]. The purpose of people’s brain is to optimize the language, such as word form and sentence structure as much as possible to reduce consumption of calories, especially in the era when it lacks food. This leads change to syntax in many aspects about word and sentence.

According to linguistics, English has seen a simplification of verb conjugation over time. Some irregular verb forms are replaced by regular verb forms. One well-known example is the verb “dive.” In Old English, the past tense of “to dive” was “deaf” or “dove.” But today, the regular form “dived” is more commonly used, and the irregular forms are less frequently used or considered archaic. Another example is the verb “sneak.” In the past tense, the traditional irregular form was “snuck.” However, in recent years, the regular form “sneaked” has become more prevalent, and some linguistic authorities now consider “snuck” as non-standard or colloquial. The reason of shift is that the regular forms are easier to be remembered. Irregular verb forms often require specific memorization of each form, which can be more challenging than applying consistent rules for regular verb forms.

Also, Old English had a complex system of grammatical cases, similar to modern German. However, over time, English underwent a simplification process, resulting in the loss of many case distinctions. For instance, Old English had a more robust system of noun declensions that indicated grammatical case, such as nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, and instrumental. However, modern English has largely lost these case distinctions. Nouns generally have the same form regardless of their grammatical role in a sentence, with only a few remnants such as the genitive case marker’s (e.g., “Amy’s book”). This change reflects the cognitive bias towards simplifying complex grammatical structures for improved efficiency.

Additionally, in sentence processing, there is a preference for subject-verb-object (SVO) word order, which is commonly found in languages worldwide. While it is challenging to provide an exact number, a large number of languages across different language families predominantly use the SVO word order. For example, English, Spanish, French, Portuguese, German, Russian, Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Swahili. This preference is believed to stem from cognitive processes that facilitate efficient parsing and comprehension.

2.3.2. Sociocultural Factor

Sociocultural psychological factors can shape grammar change based on group consciousness [13]. For instance, in the late 20th century, there was a growing recognition and acceptance of diverse gender identities. With the increasing of understanding to people who identify outside of the male/female binary, people discuss about the pronouns that can address them and tend to use gender-neutral pronoun in daily communication. The use of “they” as a singular gender-neutral pronoun gained traction as a solution to this linguistic gap. Furthermore, this usage of “they” as a singular pronoun received increased attention and acceptance in various contexts, including academia, activism, and mainstream media, throughout the early 2000s. It has become more widely recognized and embraced as a grammatically correct and inclusive alternative to gender-specific pronouns.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, psychological factors have profound impacts on the change of phonology, semantics, and syntax in linguistics. When people analyse the change in linguistics, it is unavoidable to consider the influence of psychological factors due to the nature of languages. Psychology helps linguists understand why the transformation of languages is not completely decided by the natural process but impeded by the unpredictable psychological factors. And for psychological factors, it is radical to know that human use languages to communicate and cooperate more efficiently to survive. Just picture the process how human create languages: in ancient time when a group of hunters were catching their preys, they found it was faster to communicate with partners by sounds which do not need body postures. In this way, they had not to move their sighting away from the animals, so they had more possibility to capture the food successfully and support their tribes to continue to reproduce. In such kind of general process, languages are created. And nowadays, although languages have had its relatively basic and complete form, the general process do not stop. People are still in the general process of using and creating languages, and it still influences and changes the elements of languages. Totally, the research and understanding of psychology support the study of linguistic change.

References

[1]. Tun P A, Wingfield A. One voice too many: Adult age differences in language processing with different types of distracting sounds[J]. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 1999, 54(5): P317-P327.

[2]. Gee J P. Reading as situated language: A sociocognitive perspective[M]//Theoretical models and processes of literacy. Routledge, 2018: 105-117.4

[3]. Pain R. Gender, race, age and fear in the city[J]. Urban studies, 2001, 38(5-6): 899-913.

[4]. Tajfel H, Turner J C, Austin W G, et al. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict[J]. Organizational identity: A reader, 1979, 56(65): 9780203505984-16.

[5]. raus M W, Tan J J X, Tannenbaum M B. The social ladder: A rank-based perspective on social class[J]. Psychological Inquiry, 2013, 24(2): 81-96.

[6]. Gal S. Peasant men can’t get wives: Language change and sex roles in a bilingual community[J]. Language in society, 1978, 7(1): 1-16.

[7]. Wells J C. Accents of English: Volume 1[M]. Cambridge University Press, 1982.

[8]. Smith E R, Semin G R. Socially situated cognition: Cognition in its social context[J]. Advances in experimental social psychology, 2004, 36: 57-121.

[9]. Winter B, Wedel A. The co‐evolution of speech and the lexicon: The interaction of functional pressures, redundancy, and category variation[J]. Topics in cognitive science, 2016, 8(2): 503-513.

[10]. Lewin K. Forces behind food habits and methods of change[J]. Bulletin of the national Research Council, 1943, 108(1043): 35-65.

[11]. Schunk D H. Self-efficacy and academic motivation[J]. Educational psychologist, 1991, 26(3-4): 207-231.

[12]. Billig M. Prejudice, categorization and particularization: From a perceptual to a rhetorical approach[J]. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1985, 15(1): 79-103.

[13]. Burns T R, Engdahl E. The social construction of consciousness. Part 1: collective consciousness and its socio-cultural foundations[J]. Journal of Consciousness studies, 1998, 5(1): 67-85.

Cite this article

Li,C. (2023). The Influences of Psychology on Linguistics Change. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media,27,237-243.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Volume title: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Tun P A, Wingfield A. One voice too many: Adult age differences in language processing with different types of distracting sounds[J]. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 1999, 54(5): P317-P327.

[2]. Gee J P. Reading as situated language: A sociocognitive perspective[M]//Theoretical models and processes of literacy. Routledge, 2018: 105-117.4

[3]. Pain R. Gender, race, age and fear in the city[J]. Urban studies, 2001, 38(5-6): 899-913.

[4]. Tajfel H, Turner J C, Austin W G, et al. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict[J]. Organizational identity: A reader, 1979, 56(65): 9780203505984-16.

[5]. raus M W, Tan J J X, Tannenbaum M B. The social ladder: A rank-based perspective on social class[J]. Psychological Inquiry, 2013, 24(2): 81-96.

[6]. Gal S. Peasant men can’t get wives: Language change and sex roles in a bilingual community[J]. Language in society, 1978, 7(1): 1-16.

[7]. Wells J C. Accents of English: Volume 1[M]. Cambridge University Press, 1982.

[8]. Smith E R, Semin G R. Socially situated cognition: Cognition in its social context[J]. Advances in experimental social psychology, 2004, 36: 57-121.

[9]. Winter B, Wedel A. The co‐evolution of speech and the lexicon: The interaction of functional pressures, redundancy, and category variation[J]. Topics in cognitive science, 2016, 8(2): 503-513.

[10]. Lewin K. Forces behind food habits and methods of change[J]. Bulletin of the national Research Council, 1943, 108(1043): 35-65.

[11]. Schunk D H. Self-efficacy and academic motivation[J]. Educational psychologist, 1991, 26(3-4): 207-231.

[12]. Billig M. Prejudice, categorization and particularization: From a perceptual to a rhetorical approach[J]. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1985, 15(1): 79-103.

[13]. Burns T R, Engdahl E. The social construction of consciousness. Part 1: collective consciousness and its socio-cultural foundations[J]. Journal of Consciousness studies, 1998, 5(1): 67-85.